Your 6-year-old just ripped through eight presents in four minutes. Now she’s asking “Is that all?” Meanwhile, your teenager rolls his eyes at the “boring” gift card while your toddler plays happily with the wrapping paper, oblivious to the expensive toy inside.

I’ve watched this exact scene unfold in my house—eight times over, with kids ranging from age 2 to 17. And my librarian brain couldn’t let it go without understanding why some children seem naturally grateful while others struggle, despite being raised in the same home with the same values.

Here’s what I discovered: gratitude isn’t a personality trait your child either has or doesn’t have. It’s a skill that develops in predictable stages.—and understanding those stages changes everything about how we approach gift-giving with our kids.

Key Takeaways

- Children develop gratitude in predictable stages—the shift from appreciating gifts to appreciating givers happens between ages 7-14

- Forced thank-yous build indebtedness (obligation) rather than genuine gratitude (connection)

- By age 5, children already prefer generous people and expect grateful recipients to reciprocate kindness

- Match your expectations to your child’s developmental stage—a 7-year-old genuinely can’t fully appreciate “it’s the thought that counts”

- Creating a family gift philosophy helps you make consistent decisions aligned with your values

Why Gift Philosophy Matters More Than You Think

Every gift moment is a values lesson hiding in plain sight.

When your child opens a present, their brain isn’t just processing “new thing.” They’re learning about generosity, relationships, and what matters. A 2024 study published in the European Journal of Psychology of Education found something fascinating: even in kindergartners, children’s values directly predict their social behavior. Kids with “self-transcendence values”—concern for others’ wellbeing—showed significantly more prosocial behavior, while those focused on self-enhancement showed more antisocial patterns.

The researchers define values as “guiding principles in individuals’ lives that motivate their aspirations to achieve desired goals across different life domains—to be supportive and considerate of family and friends, to be perceived as successful.”

That’s a mouthful. But the practical takeaway is powerful: the values we cultivate around gifts—including environmental consciousness—shape how our children treat people.

This doesn’t mean every unwrapped present needs to become a teaching moment. (Please, no.) But it does mean that our family’s approach to giving and receiving—our gift philosophy—matters for reasons beyond manners.

Understanding the science behind why gifts matter to children helps explain this connection. Gift exchanges activate the same brain regions involved in social bonding, trust, and relationship formation. When we’re intentional about these moments, we’re not just teaching etiquette—we’re shaping character.

What Gratitude Actually Is (And What It Isn’t)

Here’s where most parenting advice gets gratitude wrong.

We conflate gratitude with compliance. Say thank you. Write the note. Look happy. But research reveals a crucial distinction that changes how we should think about raising grateful kids.

Gratitude researchers define true gratitude as “a positive social emotion that one experiences when one has benefited from another person’s goodwill.” The key word? Goodwill. Gratitude is about recognizing that someone cared enough to give—not just that you received something.

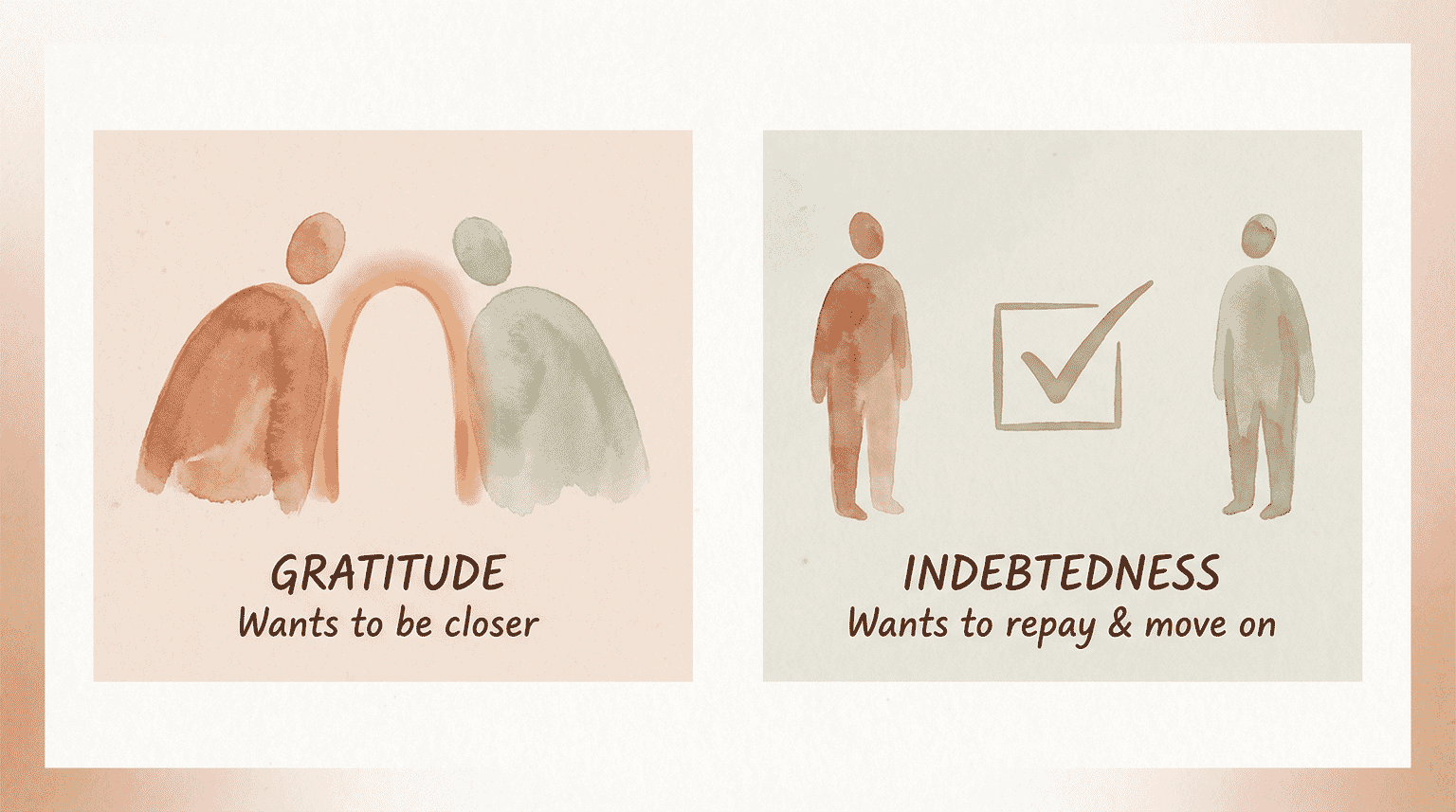

A 2025 study examining thank-you gift behavior found something that surprised me: indebtedness, not gratitude, predicts whether people give thank-you gifts. The researchers put it starkly: “Indebtedness leads more to a subjective sense of obligation to reciprocate the help one has received (but does not lead to proximity seeking), whereas gratitude leads to proximity seeking (but does not lead to an obligation to reciprocate).”

Translation? Feeling grateful makes you want to be closer to someone. Feeling indebted makes you want to repay them—and then maybe keep your distance.

This distinction matters enormously for parenting. When we force thank-you notes and demand grateful performances, we may be building indebtedness—a sense of obligation—rather than authentic gratitude. Our kids learn to check the box, not to feel genuine appreciation.

I’ve seen this with my own children. The forced thank-you note written through tears? Checked off a social obligation. The spontaneous “Mom, I love how Grandma always remembers I like dinosaurs”? That’s real gratitude in action.

The Concrete-to-Connective Shift

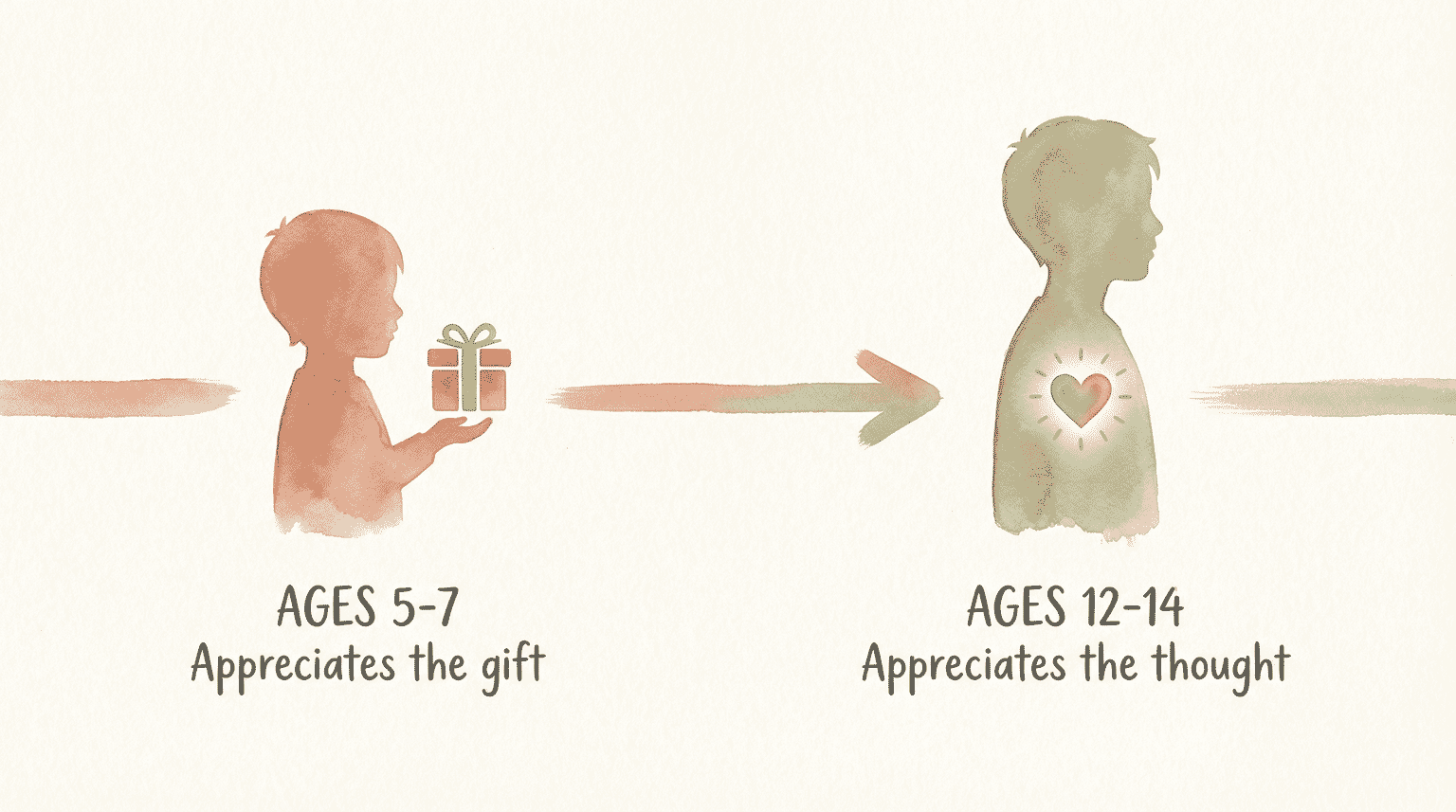

Research spanning six countries and over 2,500 children identified a universal pattern in gratitude development. Young children experience “concrete gratitude”—they appreciate the gift itself. Older children develop “connective gratitude”—they appreciate the giver’s thoughtfulness and the relationship.

This shift happens gradually between ages 7 and 14, and it’s remarkably consistent across cultures from the United States to Brazil to South Korea. Your 8-year-old genuinely can’t fully appreciate “it’s the thought that counts”—their brain isn’t there yet. By 12 or 13, they’re starting to get it.

Toddlers (Ages 2-3): Building the Foundation

Let’s be realistic about what’s happening developmentally.

Your toddler lives in a world where they are the center of the universe. Not because they’re selfish—because their brain literally cannot yet conceptualize that other people have different thoughts, feelings, and intentions. This is normal. This is healthy. And it completely shapes what we can expect around gifts.

What You Can Realistically Expect

At this age, children cannot genuinely understand why someone chose a gift or appreciate the effort behind it. They also can’t reliably mask disappointment—and shouldn’t be expected to. Research on prosocial lying development found that 3-year-olds averaged only 1.66 successful “polite lies” out of 10 attempts when given unwanted gifts.

In my house, this looked like my then-3-year-old loudly announcing “I already have this!” while holding a duplicate toy at her birthday party. Mortifying? Yes. Developmentally appropriate? Also yes.

The research confirms what every parent of a toddler already knows: expecting a 3-year-old to gracefully hide disappointment is asking for something their brain simply cannot deliver yet.

Building Receiving Skills

Focus on routine, not understanding. “We say thank you when someone gives us something” works as a simple rule, even without deep comprehension. Model genuine appreciation yourself—your toddler is watching.

Keep it physical: a hug, a smile, saying “thank you” with help. Don’t expect explanations of why they’re grateful.

Building Giving Skills

Toddlers can begin watching you select, wrap, and give gifts. Narrate what you’re doing: “We’re picking something Grandma would like. She loves flowers, so let’s get her this.”

Don’t expect independent gift-selection—that’s years away. This is parallel play with generosity.

When They’re Disappointed

Acknowledge feelings without demanding they mask them: “You wanted something different. That’s okay to feel.” Then redirect. Processing happens later; performance isn’t required.

“When your toddler says ‘I don’t like it!’ try: ‘You wanted something different. Let’s say thank you to Grandma, and we can talk about feelings later.'”

— Practical script for toddler gift moments

Preschoolers (Ages 4-5): Emerging Social Awareness

Something remarkable happens around age 5.

A 2022 study from Developmental Psychology found that 5-year-olds don’t just say thank you—they actively prefer people who display gratitude. They predict that gift-givers will also prefer grateful recipients. They expect grateful people to reciprocate kindness. And they distribute more resources to grateful individuals.

This is huge. Your preschooler isn’t just parroting politeness—they’re developing genuine social understanding about why gratitude matters.

What You Can Realistically Expect

Preschoolers can now tell “polite lies” about gifts they don’t love. The prosocial lying research shows dramatic improvement: 4-year-olds manage about 50% success (4.97 out of 10 attempts), while 5-year-olds succeed about 67% of the time. This requires cognitive empathy—understanding that their response affects the giver’s feelings.

I remember when my daughter, then 5, received a very… unusual… sweater from a well-meaning aunt. She looked at me, looked at the sweater, and said “Thank you, I like the purple parts.” Reader, it was entirely purple. But she was trying, and that effort represented real cognitive development.

Building Receiving Skills

Now you can start explaining why gratitude matters—not just as a rule, but because it helps people feel appreciated. “When you say thank you, it makes Grandma feel happy that she picked something for you.”

Practice identifying specific things to appreciate about gifts. Even a disappointing gift has something: the wrapping, the color, that the person was thinking of them.

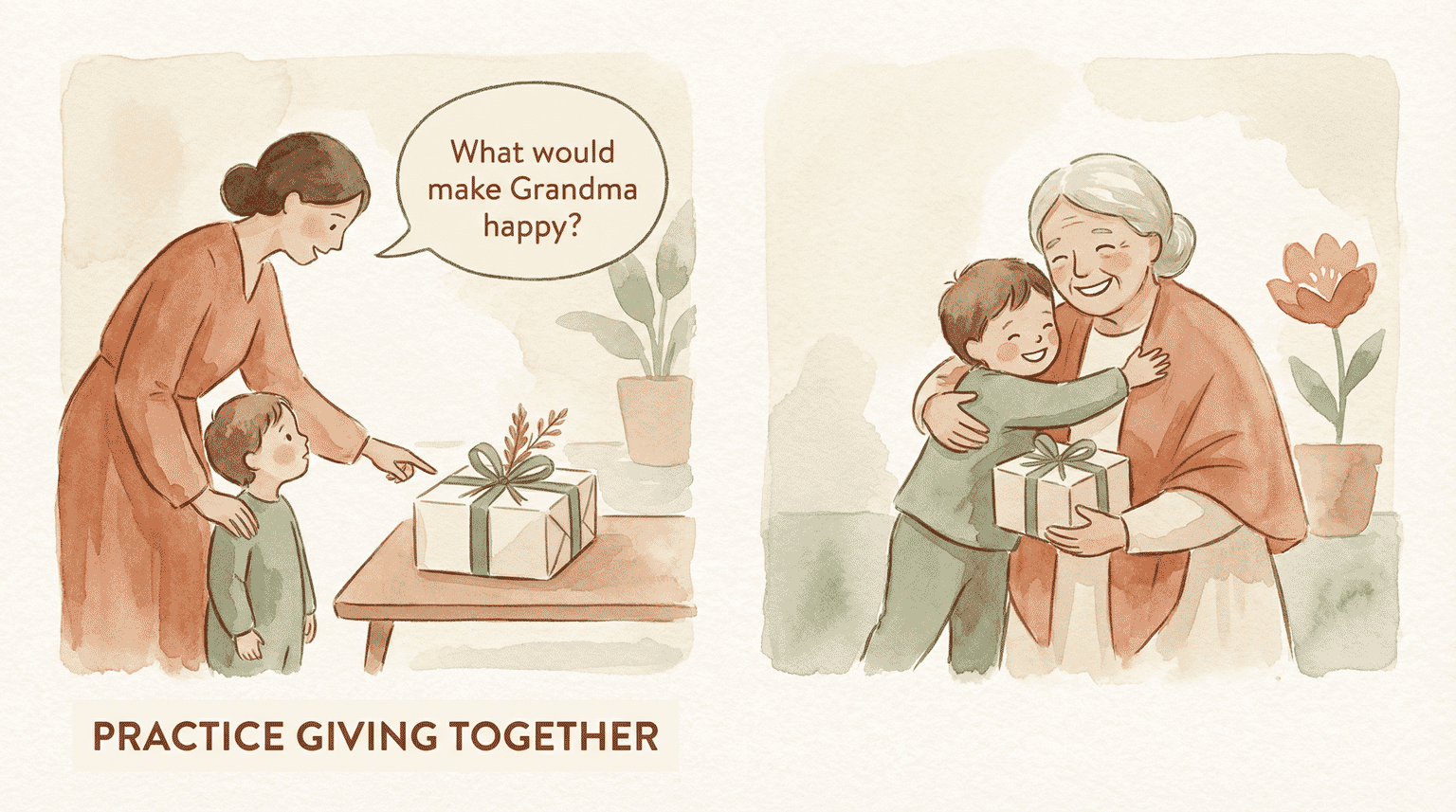

Building Giving Skills

Preschoolers can participate in gift selection with heavy guidance. Offer limited choices: “Should we get Sam the truck or the dinosaur?” They can help wrap (messily) and deliver gifts.

Start conversations about what other people might like. “What do you think makes Daddy happy?” This builds the theory of mind skills that underpin genuine generosity.

When They’re Disappointed

Your preschooler can now understand (somewhat) that we don’t want to hurt feelings. Prepare them before gift-opening: “Sometimes we get gifts that aren’t our favorite. We can still find something nice to say.”

“When your preschooler says ‘This isn’t what I wanted!’ try: ‘I hear you. Let’s think of something true and nice to say about it. What color is it? Do you like that color?'”

— Practical script for preschooler gift moments

Early Elementary (Ages 6-8): The Concrete Gratitude Years

Welcome to the phase where your child genuinely appreciates gifts—but not quite the way you’d hope.

During these years, children experience what researchers call “concrete gratitude.” They’re grateful for the thing, not the thought behind it. Your 7-year-old loves the LEGO set but can’t yet fully appreciate that Grandpa drove to three stores to find it or that it represented a financial sacrifice.

This isn’t ingratitude. It’s developmental reality.

What You Can Realistically Expect

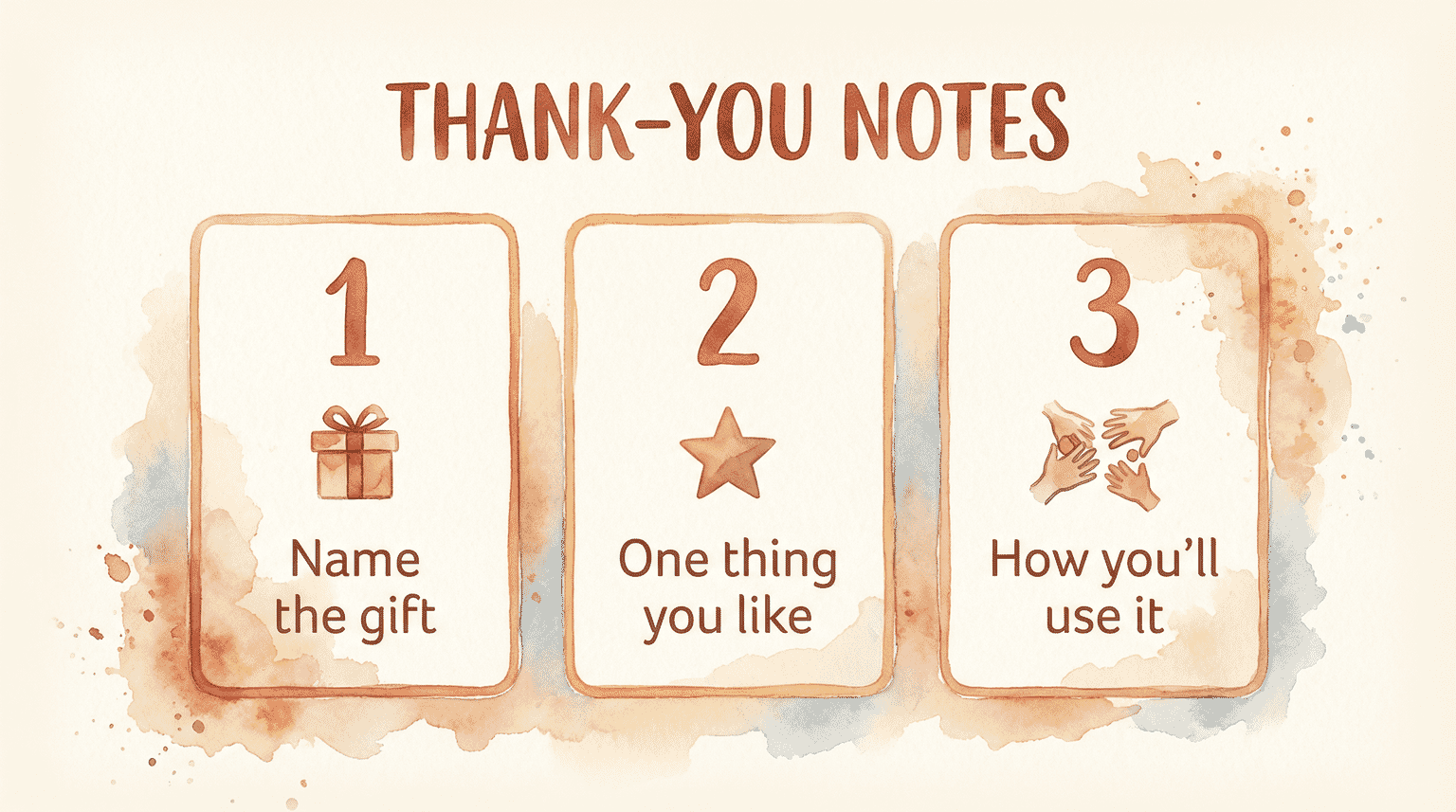

Thank-you notes can begin, but keep expectations realistic. Focus on specifics about the gift itself: “I like the red parts” or “I’m going to build the castle first.” Abstract appreciation for the giver’s effort is still emerging.

Children this age are also developing stronger opinions and may express disappointment more strategically—saving their real reactions for after the giver leaves.

Building Receiving Skills

Start connecting gifts to givers’ intentions at a simple level: “Grandma remembered you love space. That’s why she picked the rocket ship.” Plant seeds for connective gratitude even though they’re still in the concrete phase.

Thank-you notes work best when they include: naming the specific gift, one specific thing they like about it, and one way they plan to use it. Skip the “thank you for thinking of me” language—it doesn’t resonate yet.

Building Giving Skills

Early elementary children can select gifts independently within parameters. “We have $15 for Maya’s birthday present. What do you think she’d like?”

This is prime time for teaching gift-selection thinking: “What does your friend like? What would make them happy?” Some children may need help separating “what I would want” from “what they would want.”

A study of parents raising morally-developed children found that families emphasized: “I always tell my children to try to act in the community in a way that is helpful to others and help them.” Elementary years are perfect for putting this into action through gift-giving practice.

When They’re Disappointed

Children this age can delay expressing disappointment—but they’ll need to process it eventually. Create space for honest conversations later: “I noticed you seemed disappointed about the puzzle. Want to talk about it?”

“When your elementary child seems underwhelmed, try (later, privately): ‘It’s okay that the gift wasn’t your favorite. Let’s talk about how to handle those feelings while still being kind.'”

— Practical script for elementary gift moments

Preteens (Ages 9-12): The Shift to Connective Gratitude

This is when it starts clicking.

The cross-cultural research shows children transitioning from concrete to connective gratitude during these years. Your 11-year-old is beginning to genuinely appreciate not just the gift, but the relationship it represents—the fact that someone thought about them, made an effort, sacrificed time or money.

What You Can Realistically Expect

Preteens can express appreciation for the giver’s thoughtfulness and effort, not just the gift itself. “Thanks, Grandma—I know you looked hard for this” becomes genuine, not scripted.

They’re also developing more sophisticated disappointment management and can process conflicting feelings (grateful for the thought, disappointed in the gift) simultaneously.

Building Receiving Skills

Now you can have real conversations about gratitude as a relational virtue. Reference the research finding that “grateful people try to do something nice for those who have helped them”—gratitude isn’t passive appreciation but active reciprocity.

Thank-you notes can include: recognition of the giver’s effort or thoughtfulness, how the gift connects to something the giver knows about them, and authentic expression of the relationship.

Building Giving Skills

Preteens can budget, plan, and execute meaningful gift-giving independently. They can consider multiple factors: the recipient’s interests, available budget, occasion appropriateness.

This is excellent practice for the generous thinking they’ll need as adults. Involve them in family gift discussions: “What should we get Aunt Maria for her birthday? What would be meaningful to her?”

When They’re Disappointed

Preteens can process disappointment as a growth opportunity. “What would have made this gift better? How can you communicate your preferences for next time while still being grateful?”

Help them understand that graciously receiving imperfect gifts is a lifelong skill. I’ve received plenty of gifts I didn’t love over the years—and learning to genuinely appreciate the gesture while managing my own expectations has been valuable.

“When your preteen expresses disappointment, try: ‘I get it. The gift wasn’t what you hoped. But Grandpa was trying to show he loves you. What’s one true thing you can appreciate about his effort?'”

— Practical script for preteen gift moments

Experience vs. Material Gifts: What Actually Works

Here’s a question I get constantly: should we give more experiences and fewer things?

The research suggests it depends on the child’s age.

Younger children (under 7 or so) often struggle to fully appreciate experience gifts at the time of giving. Opening a card that says “We’re going to the zoo next month!” doesn’t deliver the same dopamine hit as unwrapping a toy they can hold immediately. The experience might be wonderful—but the gift-giving moment itself may feel anticlimactic.

As children develop, experience gifts “land” better. Preteens and teens can anticipate, appreciate, and remember experiences in ways that make them meaningful gifts.

The Quality vs. Quantity Question

The same study of high-moral-development families emphasized “satisfaction and saving over consumption.” Parents reported actively teaching contentment: “Satisfaction and saving are also very important, so we always advise children not to overspend and instead help others in need.”

I learned this lesson the hard way. That Christmas where my 5-year-old melted down after 12 gifts? Too much. Her brain couldn’t process it. Now we follow a simplified approach—fewer gifts, more presence during opening, more time between presents. The result is genuine appreciation rather than overwhelm.

The minimalist approach isn’t about deprivation—it’s about creating space for real gratitude to emerge.

Building Your Family Gift Philosophy

Now for the practical part: what does this look like in real life?

Start With Your Values

Before determining gift rules, clarify what you’re trying to teach. Some families prioritize:

- Generosity over accumulation

- Experiences over things

- Quality time over material goods

- Thoughtfulness over expense

- Giving over receiving

There’s no wrong answer. But having clarity helps you make consistent decisions.

Create Structures That Support Your Values

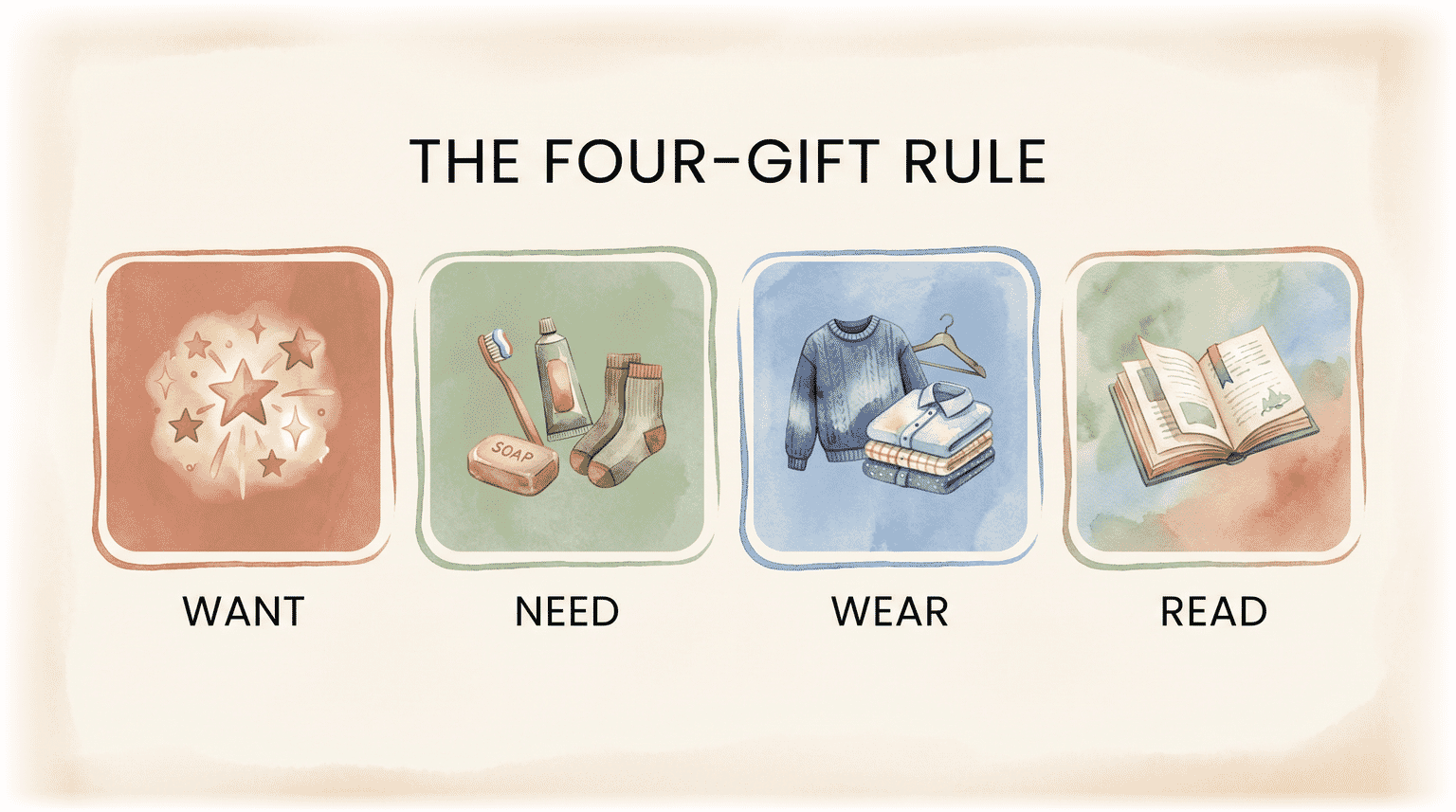

Many families use frameworks like the “four-gift rule” (want, need, wear, read). Others emphasize charitable giving alongside receiving. Some prioritize experience gifts for major occasions.

The families in the research who raised morally-developed children shared one consistent practice: regular family meetings. One parent described: “We hold family meetings every Friday, which is held continuously, we review all the things we do during the week, as well as our speech and behavior.”

These meetings don’t have to be formal or long. Even a brief weekly check-in creates space for discussing values, including around giving and receiving.

For more specific frameworks and rituals, see our guide to creating meaningful family gift traditions.

Communicate With Extended Family

This is often the hardest part. Grandparents and relatives have their own gift-giving philosophies, and navigating differences requires diplomacy.

A few approaches that work:

- Share your philosophy before occasions, not as criticism after

- Offer specific alternatives: “We’re focusing on experiences this year—would you want to contribute to her zoo membership?”

- Express genuine appreciation for their generosity while redirecting: “We love that you want to spoil her! Here are some ideas that would really excite her…”

For more on navigating these conversations, including scripts for different situations, see solutions for common gift-giving challenges.

Everyday Gift Moments (Beyond Holidays)

Gift philosophy isn’t just for December. These skills develop year-round.

Birthday Party Navigation

Birthday parties involve both receiving (your child’s party) and giving (attending others’ parties). Both are practice opportunities.

For hosting: Consider how many gifts feels manageable. Some families open presents after guests leave to reduce overwhelm and comparison dynamics. Others make it brief and move on to activities quickly.

For attending: This is perfect giving practice. Help your child think about what the birthday child would enjoy. Review expectations before arriving: “When Sofia opens your gift, she might love it or she might be more excited about something else. Both are okay.”

Sibling Gift Dynamics

Sibling comparisons around gifts are inevitable. One strategy from the research: when a new sibling arrives, “we gave a gift to my daughter (who was 3-year old) from her brother. This made her feel good about her brother.”

This “welcome gift” approach addresses a child’s feeling of displacement through connection rather than competition. The gift isn’t compensation—it’s relationship-building.

The Digital Factor

Modern gift culture includes digital components that create new challenges—wishlists, tracking packages in real-time, instant-gratification expectations. Understanding navigating digital gift culture with kids helps address these contemporary pressures.

Common Challenges (And What Actually Helps)

“My Child Expressed Disappointment Publicly”

Deep breath. This happens to every parent. Your immediate response matters less than the follow-up conversation.

In the moment: Redirect briefly (“Let’s say thank you to Grandma”) without shaming. Later: Process together—”What happened there? What could you do differently next time?”

“The Grandparents Won’t Stop Over-Gifting”

This requires ongoing conversation, not one-time boundary-setting. Some options:

- Request contributions to a college fund or experience fund

- Suggest consumables (art supplies, building materials) over toys

- Ask them to be “the person who gives X” (books, craft supplies, sports equipment)

- Accept that some compromise is okay for relationship preservation

“Siblings Compare Who Got More”

Comparison is developmentally normal. But you can reduce its power:

- Avoid dollar-based equality (teaches them to calculate)

- Focus on “thoughtfulness for each person” rather than fairness metrics

- Acknowledge feelings: “It’s hard when someone else’s gift looks exciting”

“My Child Says Thank You But Doesn’t Mean It”

Remember the gratitude vs. indebtedness distinction. Performative thanks may create obligation, not appreciation.

Instead of forcing feeling, try building understanding: “What do you think Aunt Sarah was hoping you’d feel when she gave you this?” or “Why do you think she chose this particular thing?”

Over time, understanding builds authentic appreciation better than demanded performance.

Cultural Considerations

Gift-giving norms vary significantly across cultures, and understanding this helps both in raising globally-aware children and navigating multicultural family dynamics.

The thank-you gift study found significant cultural differences: 71.2% of Asian students gave thank-you gifts compared to 58.6% of European American students. But Asian students were less likely to maintain relationships with benefactors afterward—suggesting the gift functioned more as debt-repayment than relationship-building.

The cross-cultural gratitude research found universal developmental patterns (the concrete-to-connective shift) but cultural variation in how gratitude is expressed and expected. What’s considered “grateful enough” in one culture may seem insufficient or excessive in another.

For multicultural families, this means:

- Different family members may have different expectations

- Neither set of norms is “right”—they’re culturally shaped

- Helping children understand variation builds flexibility

- Explicit discussion reduces misunderstanding

The Long-Term View: Why This Matters

Sometimes, in the chaos of unwrapped presents and thank-you note nagging, it’s hard to see the bigger picture.

But the research is clear: the values we cultivate early have lasting effects. The 2024 study found that self-transcendence values in kindergartners predicted prosocial behavior. Earlier research established that values serve “as protective factors against violent behavior.”

The connection between gratitude and generosity matters beyond gift-giving occasions. Children who learn to genuinely appreciate others’ goodwill develop stronger relationships. Children who learn to give thoughtfully develop empathy and connection.

I think about this when I watch my teenagers—the ones who were once the toddlers announcing “I already have this!” at birthday parties. They’re now capable of genuine connective gratitude, real appreciation for effort and thoughtfulness, independent and thoughtful gift-giving.

It didn’t happen through lectures or punishment. It happened through modeling, conversation, age-appropriate expectations, and lots of grace for developmental reality.

The goal isn’t perfect gift-receiving children. It’s raising humans who understand that gifts are really about relationships—and who feel genuine gratitude for being loved.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I teach my child to be grateful for gifts?

Match your approach to your child’s development. Preschoolers learn through modeling—they naturally prefer grateful people. Elementary children are in the “concrete gratitude” phase, appreciating gifts themselves before understanding givers’ intentions. Around ages 9-12, children shift to “connective gratitude” and can genuinely appreciate the relationship and effort behind a gift. Focus on modeling genuine appreciation rather than forcing compliance.

At what age can children understand gratitude?

Children develop gratitude in stages. By age 5, research shows children prefer grateful recipients and expect them to reciprocate. However, young children experience “concrete gratitude”—focused on the gift itself. Between ages 7-14, children gradually develop “connective gratitude,” appreciating the giver’s thoughtfulness and the relationship. This shift is universal across cultures.

Why is my child ungrateful for gifts?

What looks like ingratitude is often developmentally normal. Children under 10 typically experience “concrete gratitude”—they appreciate gifts, not givers’ intentions. They can’t genuinely understand “it’s the thought that counts” until their brains develop capacity for perspective-taking, which emerges gradually through elementary years. This isn’t character failure; it’s cognitive development.

Should I make my child write thank-you notes?

Match expectations to development. Research shows only about 30% of college students write thank-you notes, and those who do are motivated by indebtedness (obligation) rather than gratitude (warmth). For young children, verbal thanks with a specific detail works well. Written notes can begin around ages 6-8, but focus on expressing something genuine rather than performing obligation.

How do I teach my child to give gifts to others?

Start with participation, not perfection. Preschoolers can watch you select and wrap gifts. Early elementary children can choose gifts within parameters. Preteens can budget and plan independently. Research shows children with self-transcendence values—concern for others’ wellbeing—show more prosocial behavior. Build giving skills alongside receiving skills at each stage.

I’m Curious

What gift values are you trying to teach? I’d love to hear what’s worked—and what’s proven harder than expected—as you’ve tried to raise grateful, generous kids.

Your stories help me understand what actually works beyond the research.

References

- Personal values and social behavior in early childhood – Research on how self-transcendence values predict prosocial behavior in kindergartners

- Young children value recipients who display gratitude – Study showing 5-year-olds prefer and allocate more resources to grateful recipients

- The psychology of a thank-you gift: Who gives it and why? – Research distinguishing gratitude from indebtedness in gift-giving behavior

- How weird is the development of children’s gratitude in the United States? – Cross-cultural study of 2,540 children documenting the concrete-to-connective gratitude shift

- Other-Benefiting Lying Behavior in Preschool Children – Research on prosocial lying development and the “undesirable gift paradigm”

- The lived experience of parents from educating morality to children – Qualitative study of strategies used by parents raising morally-developed children

Latest in Gift Values

-

Signs You’re Over-Gifting Your Kids (And What to Do)

by

· Updated

Continue reading →: Signs You’re Over-Gifting Your Kids (And What to Do)The midnight add-to-cart spiral hits different when you’re already dreading where everything will go. Research shows cost has zero relationship with how gifts are received, and here’s how to spot when generous has tipped into overwhelming.

-

Your Child’s First Charity Donation: A 3-Step Guide

by

· Updated

Continue reading →: Your Child’s First Charity Donation: A 3-Step GuideYour child wants to help but you’re stuck wondering how much, which charity, and whether they’ll even understand what’s happening. This simple three-step framework turns that first donation into something they’ll actually remember.

-

Teaching Kids to Celebrate Others’ Joy

by

· Updated

Continue reading →: Teaching Kids to Celebrate Others’ JoyYour child’s friend just opened the coolest birthday present, and your kid looks like she’s attending a funeral. Here’s the brain science that explains why celebrating others can actually become your child’s shortcut to feeling good too.

-

Space for Imagination: The Science of Kids’ Creativity

by

· Updated

Continue reading →: Space for Imagination: The Science of Kids’ CreativityYour kid hasn’t complained about being bored in weeks, and that might actually be the problem. New research reveals why empty space in the schedule is exactly where imagination learns to stretch.

-

Want Need Wear Read: 4 Gift Rule Guide

by

· Updated

Continue reading →: Want Need Wear Read: 4 Gift Rule GuideThe wrapping paper settles, your child sits surrounded by gifts, and then comes the dreaded question. Is that all? Discover why the 4-gift rule works with brain chemistry instead of against it.

-

Why Fewer Toys Lead to Better Play Science

by

· Updated

Continue reading →: Why Fewer Toys Lead to Better Play ScienceYour child stands in a room full of toys and says they’re bored. New research reveals the surprising brain science behind this frustrating moment and exactly how many toys actually lead to deeper, more creative play.

Share Your Thoughts