Your child checks the tracking page for the third time today. The package was ordered six hours ago. Meanwhile, their wishlist has grown by four items since breakfast—each one added with a single tap, each one triggering a little dopamine hit of “wanting.”

Welcome to the wishlist app generation.

Something shifted in how children wish for things, and most of us didn’t notice until we were already managing the fallout. When I was a kid, wishlists happened once a year—a handwritten letter to Santa or a circled catalog page.. Today, my 8-year-old can add items to her digital wishlist from anywhere, anytime, with an interface specifically designed to make wishing feel frictionless and endless.

My librarian brain couldn’t let this go without digging into what’s actually happening here. What I found stopped me in my tracks.

Key Takeaways

- Wishlist apps use AI-powered “persuasion profiles” to identify your child’s vulnerabilities and maximize wanting behavior

- Commercial apps show zero positive effect on parent-child interaction—only 29% of kids use apps with adult involvement

- Children who share wishes publicly report significantly higher rates of depression and anxiety symptoms

- Most kids lack executive function for independent wishlist management until age 10-12

- Using wishlist apps together with your child dramatically improves outcomes

What Changed When Wishlists Went Digital?

Kids’ wishlist apps are digital platforms that allow children to browse, save, and share desired items—typically syncing with retail sites and enabling family members to view and purchase from the list. They’re marketed as coordination tools that prevent duplicate gifts and make holiday shopping easier.

That’s the surface story. The deeper story involves a fundamental shift in how children participate in consumer culture.

Research from Karen E. Wohlwend in The Routledge Handbook of Digital Literacies in Early Childhood identifies children as representing “three markets in one”: a primary market where they spend their own money, a secondary market where they influence parental spending, and a future market representing potential adult consumers. Wishlist apps aren’t neutral tools—they’re designed to maximize engagement across all three markets.

What researchers call “intransitive choice” describes exactly how these apps work: children feel they’re choosing freely from infinite possibilities while actually navigating a curated commercial environment designed to generate desire.

The endless scroll of products, personalized recommendations, and single-tap adding mechanics all encourage “wanting” as an ongoing activity rather than a seasonal reflection.

This connects to the broader shift in how families approach gift-giving online—a change that happened gradually enough that we didn’t recognize it until it was already our new normal.

How Do These Apps Know What Your Child Wants?

Here’s where it gets unsettling.

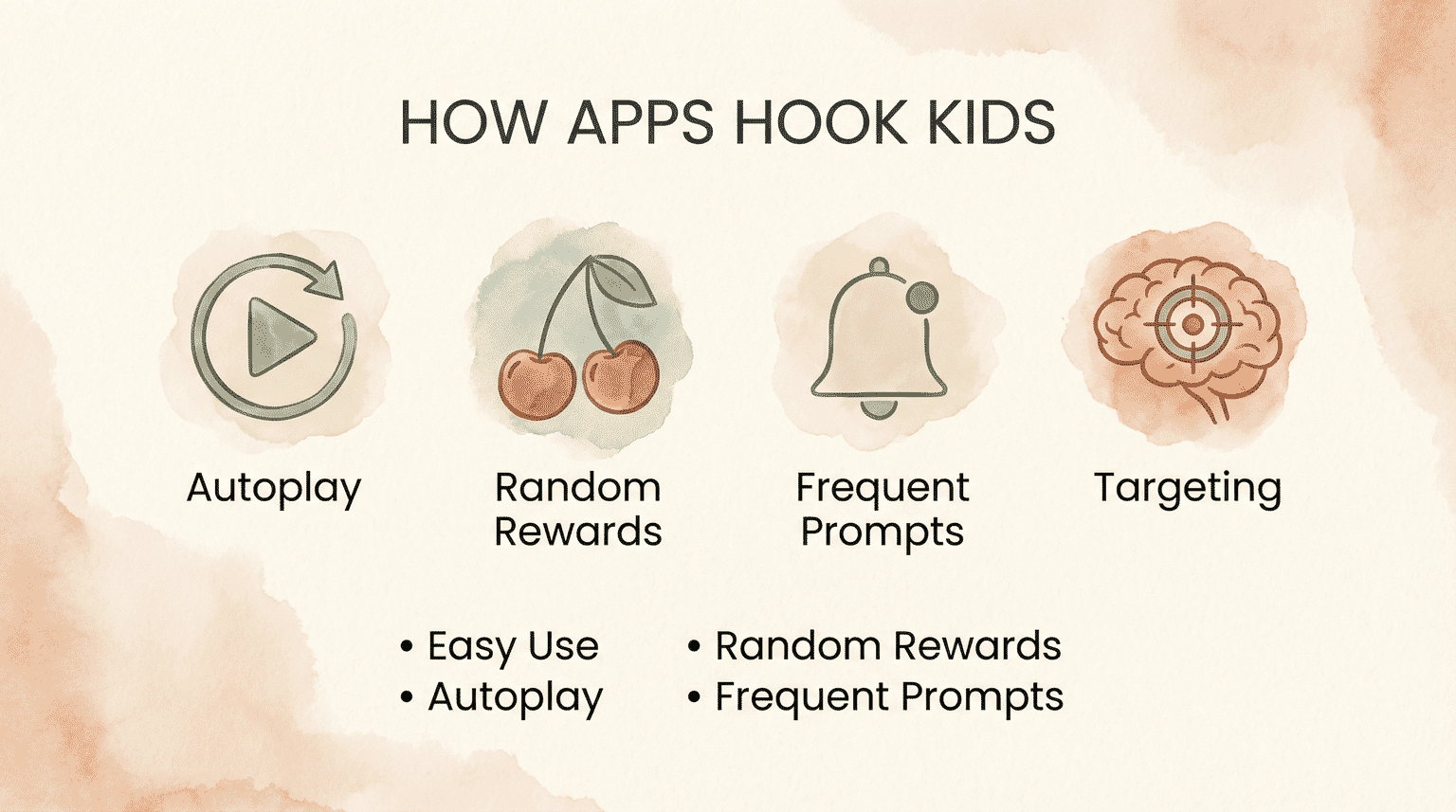

The techniques these apps use are borrowed directly from social media and gaming.

“Many platforms use artificial intelligence to create a ‘persuasion profile’ that identifies users’ vulnerabilities and produces an individualised program of content targeted toward them in real time… It’s a ruthless and antisocial strategy that puts profits ahead of the welfare of our children.”

— Wayne Warburton, Associate Professor and Developmental Psychologist, Macquarie University

This isn’t theoretical. These apps learn what captures your child’s attention, which categories they linger on, what time of day they’re most likely to add items, and which prompts trigger action. Then they deliver more of exactly that—optimized for maximum engagement.

A 2024 NIH review on digital device usage found that children engaging frequently with digital devices showed lower executive function, poorer working memory, and reduced inhibitory control. Digital environments create “continuous partial attention”—the constant, low-grade awareness that more wishes could be added, more items discovered.

I’ve watched this with my own kids. My 10-year-old will casually add something to her list while we’re talking, barely registering what she’s doing.

The barrier between “noticing something exists” and “actively wanting it” has essentially disappeared.

For a deeper look at how recommendation algorithms shape children’s desires, the mechanics go even further than most parents realize.

What Happens When Wishes Become Public?

Traditional wishlists were private communications between children and gift-givers. Digital wishlists often aren’t.

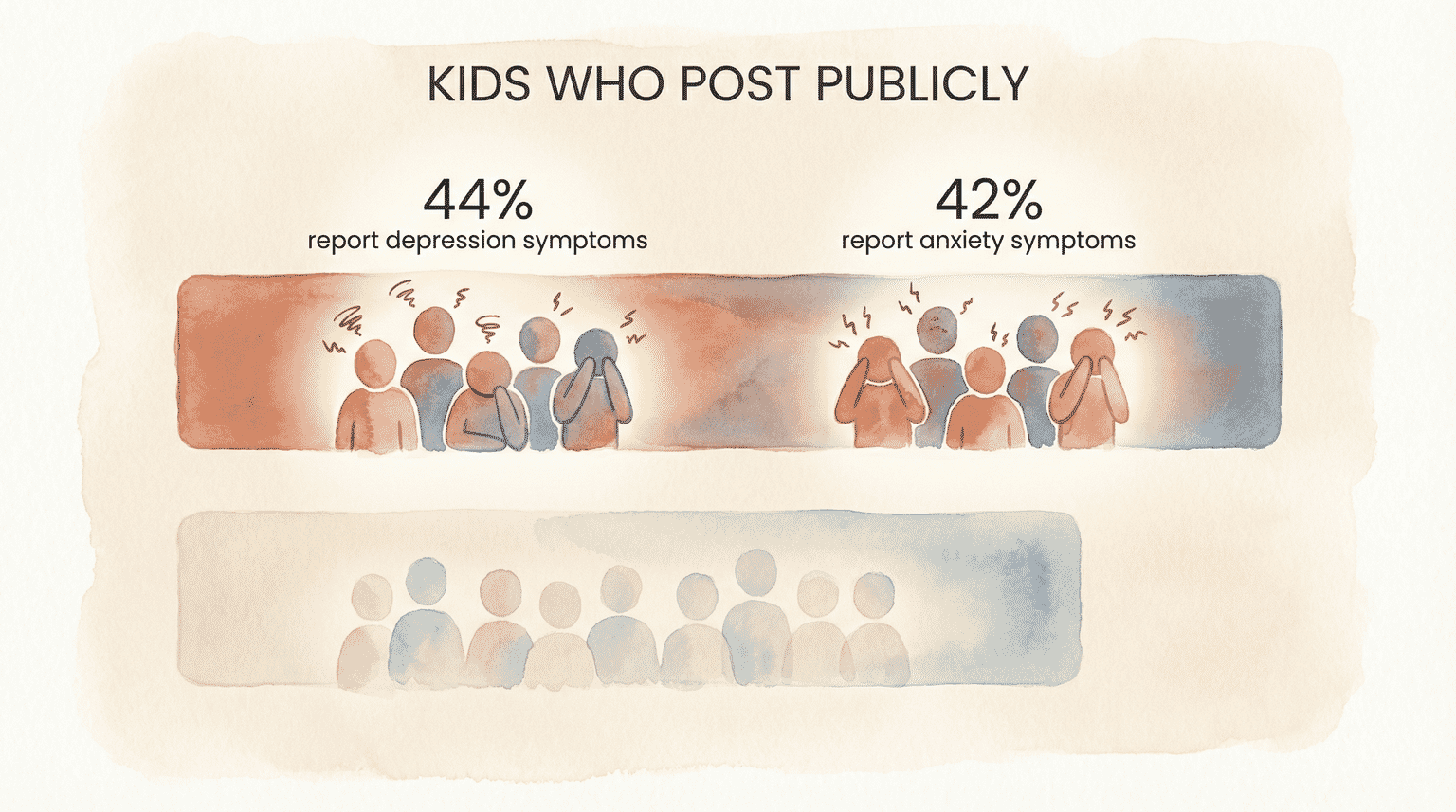

Many wishlist apps include sharing features, social components, or integration with extended family networks. Research from the American Psychological Association found that children who posted publicly on social media were significantly more likely to report symptoms of depression (44% versus 36%) and anxiety (42% versus 26%) than those who didn’t.

While wishlists aren’t identical to social media posts, they create similar dynamics when wishes become visible to peers, cousins, or family friends. Suddenly there’s comparison. Judgment. The pressure of being seen wanting things.

Dr. Anne Maheux from the University of North Carolina notes that kids feel pressure to respond immediately to digital communications—liking photos, responding to messages. Shared wishlists can create parallel pressure: Did grandma see my list? Did my cousin add the same thing? Is my list “cool” enough?

Dr. Eileen Kennedy-Moore adds another dimension: “The tricky thing about online communication is, it is attenuated communication… Misunderstandings are rife.” When wishlists replace conversations about what children actually want and why, we lose the nuance. A grandmother reading “LEGO Star Wars set” on a screen misses the excited explanation, the specific details that matter, the chance to ask questions and understand what her grandchild actually dreams about.

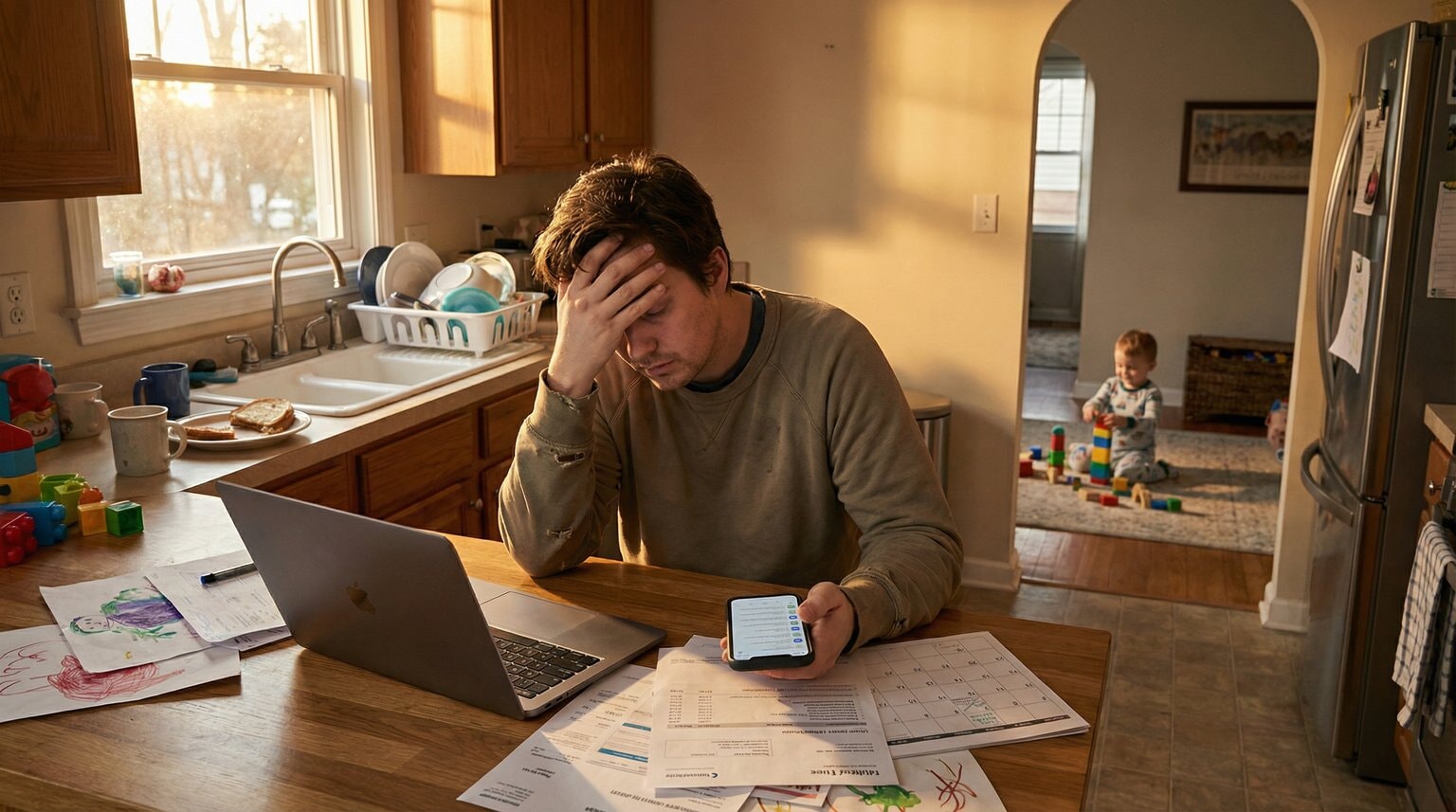

The Parent Squeeze

Here’s what the app marketing doesn’t mention: these tools transfer pressure from children to adults.

When my daughter adds something to her wishlist, that action creates work for me. Someone needs to review the list, check appropriateness, manage expectations, coordinate with family members, and handle disappointment when items remain unpurchased. The “frictionless” experience for her creates friction for everyone else.

A 2025 meta-analysis from Educational Research Review found something striking: commercial apps showed zero positive effect on parent-child interaction, compared to large positive effects from apps specifically designed with parental engagement in mind.

Only 29% of preschoolers in England typically use apps with adult involvement—meaning most children interact with these platforms in isolation.

The same research found that parents use fewer high-quality interaction strategies when sharing digital media compared to traditional media like books or games—including fewer new words and fewer questions. When wishlists went digital, we didn’t just change the format. We changed whether families actually talk about gifts at all.

There’s also an equity angle that bothers me. Wohlwend’s research reveals that because more affluent families are more likely to purchase premium app versions, children from lower-income families are most likely to encounter freemium features that negatively impact their experience. The pressure mechanics aren’t evenly distributed.

What Healthy Wishing Actually Looks Like

I’m not suggesting we ban all wishlist technology. That ship has sailed, and prohibition rarely works anyway. But we can be more intentional.

Wayne Warburton offers a useful reframe: “Think of a healthy media diet as being like a healthy food diet—it’s about moderation and good choices.”

Here’s what works in my house:

We use wishlists together rather than handing them to children independently. Research consistently shows that parental co-engagement dramatically improves outcomes across all types of digital media use. When we browse together, I can ask questions, set boundaries in real time, and keep the focus on conversation rather than consumption.

We set clear parameters before app use: a maximum number of items, rough price ranges, and the explicit understanding that wishlists are starting points for conversations—not shopping lists for adults. My 12-year-old knows her list represents ideas and possibilities, not guaranteed purchases.

For younger children, we skip the apps entirely. Most children lack the executive function for independent wishlist management until around age 10-12. My 4 and 6-year-olds still draw pictures of what they want or flip through catalogs with me. It’s slower. It’s also more meaningful.

And we talk about what actually makes gift-giving meaningful for children—which research suggests has far more to do with relationship and anticipation than the objects themselves.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are wishlist apps bad for kids?

The apps themselves aren’t inherently harmful, but their design often is. Research shows commercial apps use persuasive techniques—random rewards, vulnerability targeting, and frequent prompts—that maximize engagement rather than support healthy family gift-giving. The key factor is whether apps facilitate parent-child conversation or isolate children with their desires.

What age should kids have a wishlist app?

Most children lack the executive function for independent wishlist management until around age 10-12. Younger children benefit from parent-led approaches where adults curate wishes together through conversation. If your child can’t manage delayed gratification, understand price/value relationships, and distinguish wants from needs, they’re not ready for independent wishlist app use.

How do wishlist apps manipulate children?

Developmental psychologist Wayne Warburton explains that many platforms use AI to create “persuasion profiles” identifying users’ vulnerabilities, then deliver individualized content targeted in real time. Combined with easy use, random rewards, and frequent notifications, these techniques are engineered to maximize time-in-app and desire generation.

Do wishlists make kids more materialistic?

They can. Wishlist apps create what researchers call “intransitive choice”—children feel agency while actually navigating curated commercial environments designed to generate desire. The infinite scroll, personalized recommendations, and easy adding mechanics encourage “wanting” as an ongoing activity rather than a seasonal reflection.

How can I manage my child’s wishlist expectations?

Start by using wishlist apps together rather than handing them to children independently. Set clear boundaries before app use—number of items, price ranges, and the understanding that wishlists are starting points for conversations, not shopping lists for adults. Research shows parental co-engagement dramatically improves outcomes.

Join the Conversation

Do your kids use wishlist apps? I’m curious whether it’s made gifting easier or just created an endless scroll of wants. Would love to hear how you’ve managed expectations—or whether you’ve banned them entirely.

Your wishlist app stories help me understand how other families navigate this new reality.

References

- Features of digital media which influence social interactions – Meta-analysis on digital media and parent-child interaction

- Digital Device Usage and Childhood Cognitive Development – NIH review of screen time effects on executive function

- Many teens are turning to AI chatbots for friendship – APA research on technology and youth development

- How too much screen time is hurting our kids – Macquarie University research on persuasive design

Share Your Thoughts