You spent an hour researching the perfect toy. You watched your toddler rip off the wrapping paper in seconds. And now? She’s sitting inside the cardboard box, completely ignoring the $40 playset you carefully selected.

Before you question your gift-giving abilities, here’s some reassurance: you’re witnessing something 98% of toddlers do. A 2021 New York University study tracked 40 infants at home and found they spent nearly equal time playing with household items like boxes (30.8%) as they did with actual toys (32.3%). Your toddler isn’t rejecting your gift—her brain is doing exactly what it’s supposed to do.

My librarian brain couldn’t let this go without investigating. After watching this play out with all eight of my kids, I finally understand why boxes win. It comes down to four distinct mechanisms working in your toddler’s developing brain.

Key Takeaways

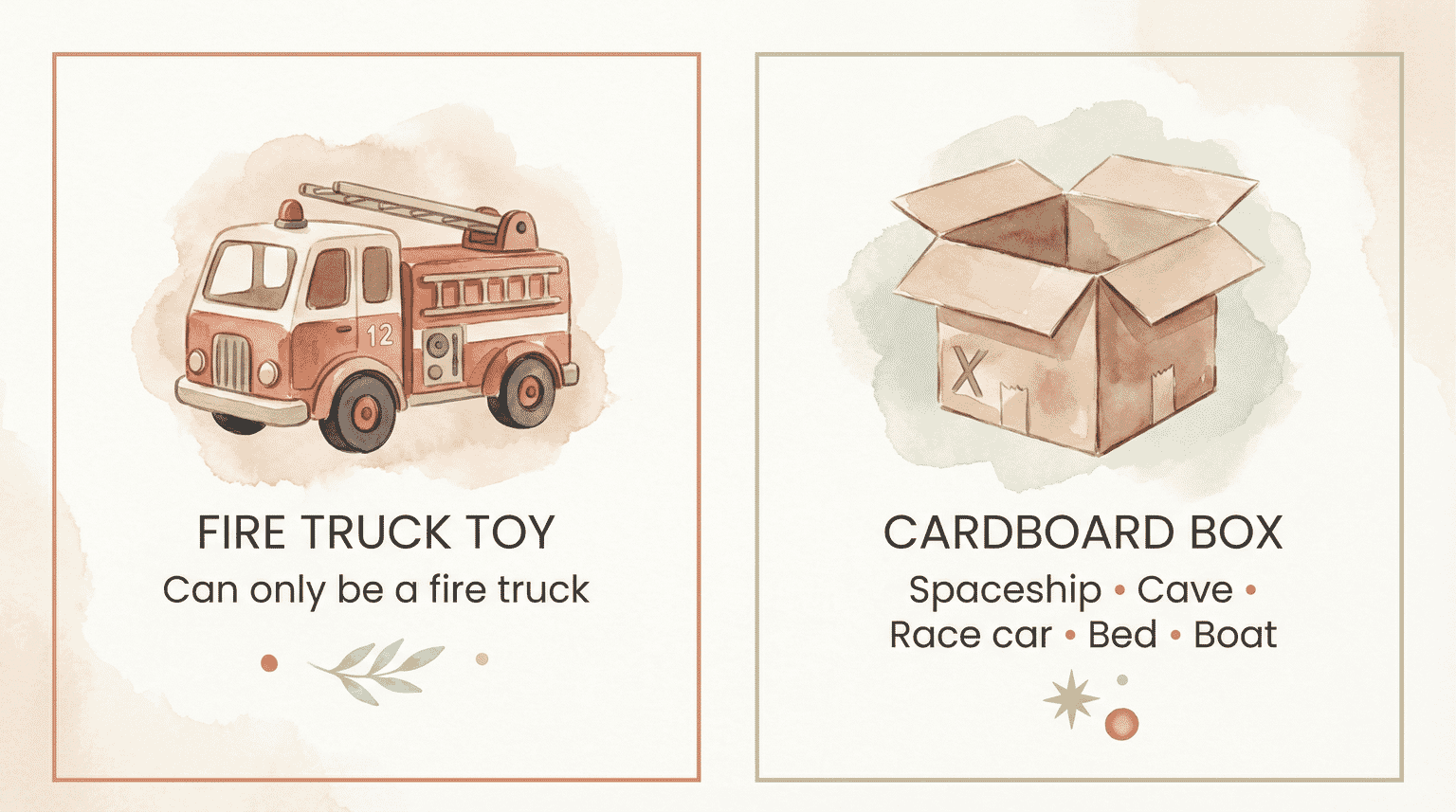

- Boxes activate open-ended imagination—a fire truck can only be a fire truck, but a box becomes anything

- Toddlers play twice as long with each toy when given fewer options—boxes offer cognitive relief from overwhelming choice

- Container play builds object permanence, cause-and-effect understanding, and spatial reasoning through repetitive exploration

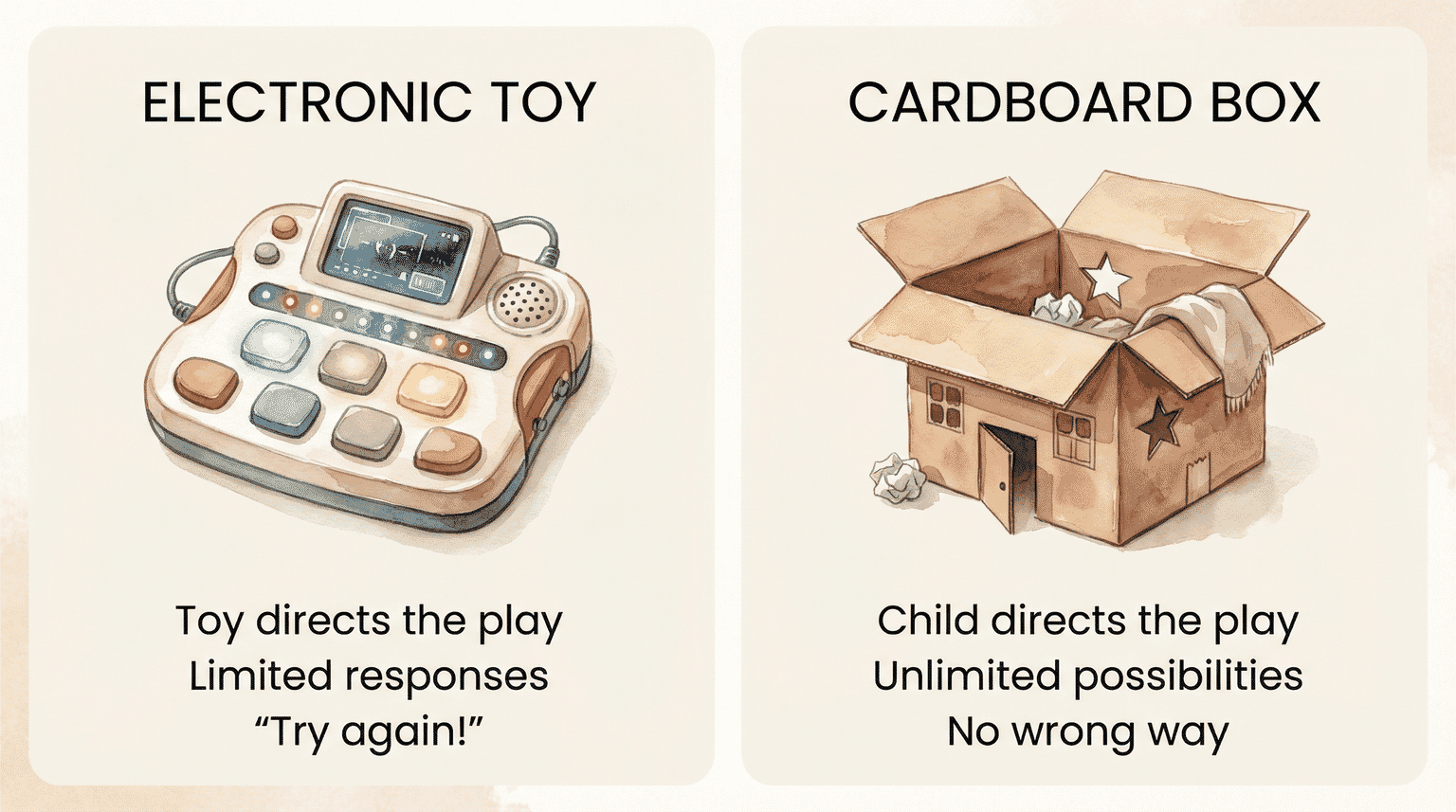

- Unlike electronic toys that direct play, boxes let children be the boss—which is exactly what their developing brains need. (This is why toddlers say “mine” so much.)

The Quick Answer

Toddlers prefer boxes over toys because boxes activate four developmental mechanisms simultaneously: open-ended imagination (a box becomes anything), optimal cognitive load (one object versus overwhelming toy piles), multi-sensory exploration (texture, sound, space), and control over play outcomes. This isn’t quirky behavior—it’s cognitively sophisticated play that supports motor, language, and problem-solving development.

Now let’s break down each mechanism so you can see what’s actually happening when your toddler abandons the toy for the packaging.

The NYU research team tracked infant play across real home environments, not laboratory settings. What they found challenges everything we assume about “proper” toys.

Household items like boxes, containers, and kitchen utensils captured nearly a third of all play time—matching expensive toys almost exactly. Your instinct to buy the fancy educational toy isn’t wrong. But neither is your toddler’s instinct to ignore it.

The Blank Canvas Effect

Why Open-Ended Beats Purpose-Built

Here’s the fundamental difference: a fire truck can only be a fire truck. A cardboard box? That’s a spaceship, a bed for stuffed animals, a hiding cave, and a race car—sometimes all within the same five minutes.

Developmental psychologists call this “open-ended play,” and it’s the first mechanism explaining your toddler’s box obsession. When there’s no predetermined purpose, your child’s brain gets to do the creative work of assigning meaning.

Lead researcher Catherine Tamis-LeMonda explains what her team observed in homes across the country.

“Despite the colorful, ‘child-designed’ features of toys, their fit to little hands, and the prevalence of toys in the homes we visited, infants played with whatever captured their interest in the moment.”

— Catherine Tamis-LeMonda, PhD, Lead Researcher, NYU Study

Ohio State’s Schoenbaum Family Center describes cardboard boxes as the perfect example of open-ended materials because they “allow children to explore and create without a specific end goal in mind, piquing their natural curiosity.”

What you’ll see at home: Your toddler transforms the same box from a boat to a drum to a tunnel in rapid succession. This isn’t random—she’s exercising symbolic thinking, a major cognitive milestone that emerges between 18 months and 3 years.

The Cognitive Load Sweet Spot

Why Less Overwhelms Less

Here’s something that surprised me when I first read the research: toddlers actually play worse when they have more toys available. The evidence for fewer toys leading to better play is remarkably consistent.

A 2023 Psychology Today analysis found that infants played twice as long with each toy when only four were present compared to twelve. With fewer options, children engaged more creatively and explored each object in multiple ways.

The cognitive explanation makes sense once you understand toddler attention. As the researchers explain, “Infants and toddlers have low levels of sustained attention. Therefore, having more toys presented to them makes it harder for them to sustain attention on one toy.”

Now consider this: the average American home has 139 toys visible and accessible to children. That’s not a play environment—it’s cognitive overload.

A single cardboard box, by contrast, represents one clear object to focus on. No competing options. No decision fatigue. Just one thing to explore thoroughly.

What you’ll see at home: Your toddler ignores the toy corner with 30 options but becomes completely absorbed by a single empty box. She’s not being difficult—her brain is finding relief from overwhelming choice.

The Multi-Sensory Exploration Drive

Why Boxes Are Developmental Playgrounds

The third mechanism involves what researchers call “container play”—and it explains why your toddler is obsessed with putting things in boxes, taking them out, and doing it again approximately 47 times.

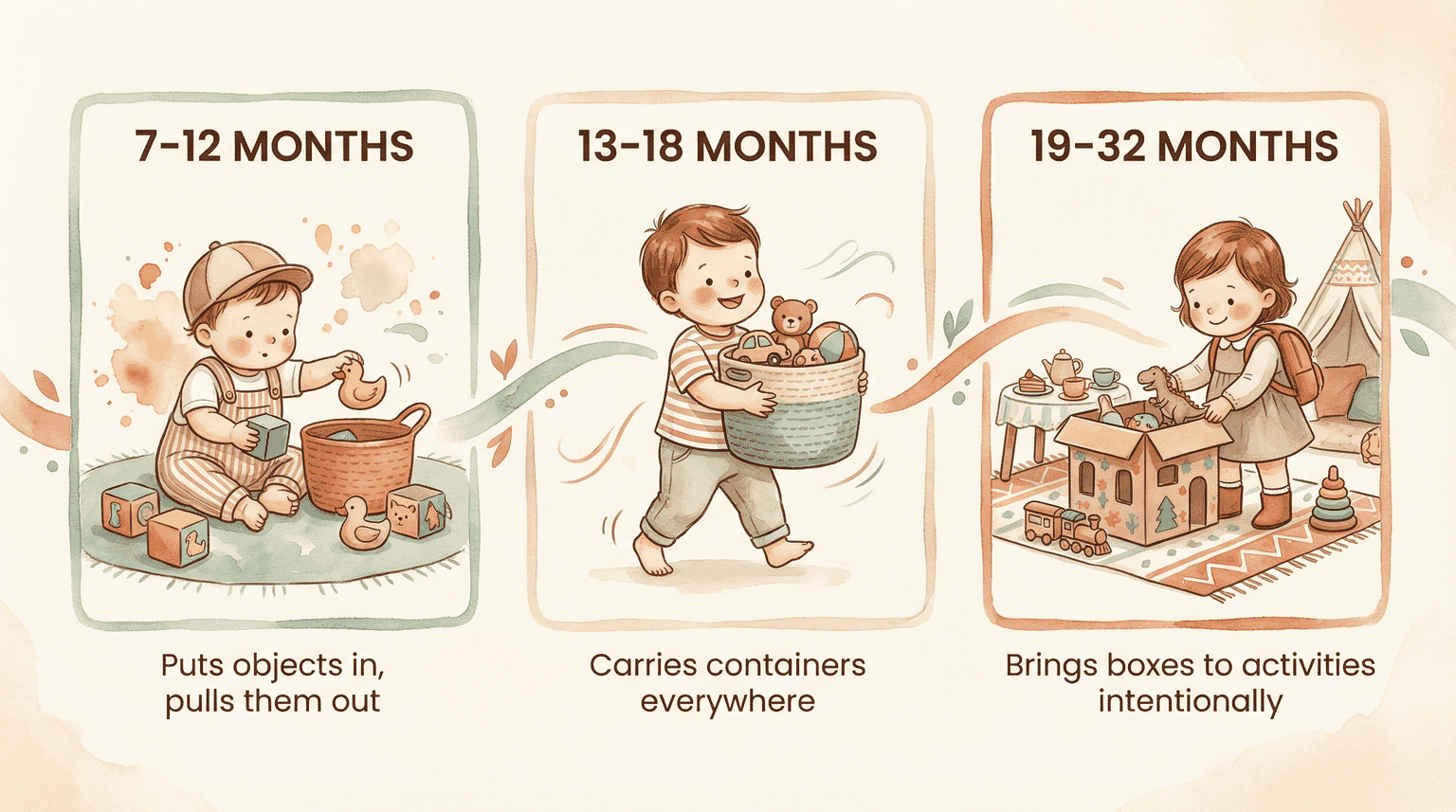

A 2023 PMC study documented how container behaviors develop across the first three years:

- 7-12 months: Children begin putting objects in and pulling them out repeatedly

- 13-18 months: After learning to walk, carrying behaviors explode—toddlers use containers to transport objects around the house

- 19-32 months: Children start bringing containers to activities intentionally and returning them afterward

This isn’t mindless repetition. Each time your toddler drops a block into a box and pulls it out, she’s learning object permanence (it still exists when I can’t see it), cause and effect (my action makes something happen), and spatial reasoning (inside versus outside, fitting versus not fitting).

Research from Education Sciences found that children’s use of objects was significantly tied to what researchers call “deep-level learning.” Specifically, learning depth increased measurably when children interacted with physical materials—and increased even more when they engaged with multiple types of objects.

Boxes deliver sensory input on multiple channels simultaneously: the texture of cardboard, the sound of tapping or tearing, the spatial experience of climbing inside, the weight of lifting and moving. Compare this to many electronic toys that offer primarily visual and auditory input in predetermined ways.

What you’ll see at home: Your toddler bangs on the box, bites the corner, tries to climb inside, tips it over, puts toys in it, dumps them out, repeats. Every “destructive” behavior is actually sensory research.

The Control and Ownership Factor

Why Being the Boss Matters

The fourth mechanism is perhaps the most important for understanding why simple beats sophisticated: toddlers crave control over their environment, and boxes give them complete authority.

When your toddler plays with a box, she decides what it is, what happens, and when it changes. The box responds to her actions without judgment or correction. There’s no “wrong way” to play with a box.

Contrast this with many modern toys—especially electronic ones. Research on caregiver-toy interactions has found that electronic toys are associated with lower quality verbal interactions. Parents use less varied language and fewer conversational turns when electronic toys are directing the play. The toy becomes the boss, not the child.

Postdoctoral fellow Orit Herzberg from the NYU study offers a powerful reframe for parents worried about their toddler’s “scattered” attention.

“Instead of viewing infant behavior as flighty and distractible, infants’ exuberant activity should be viewed as a developmental asset—an ideal curriculum for learning about the properties and functions that propels growth in motor, cognitive, social and language domains.”

— Orit Herzberg, PhD, Postdoctoral Fellow, NYU

A 2024 study on loose parts play found that open-ended materials—items not originally designed as toys but incorporated into children’s play—support impulse control, behavior regulation, exploration, and problem-solving. Unlike predetermined toys, these materials afford children the autonomy to direct their own play and foster independent thinking.

What you’ll see at home: Frustration when the “learning toy” says “Try again!” versus endless patience when the box simply… exists. Your toddler wants to be the scientist, not the subject.

What This Means for Toy Selection

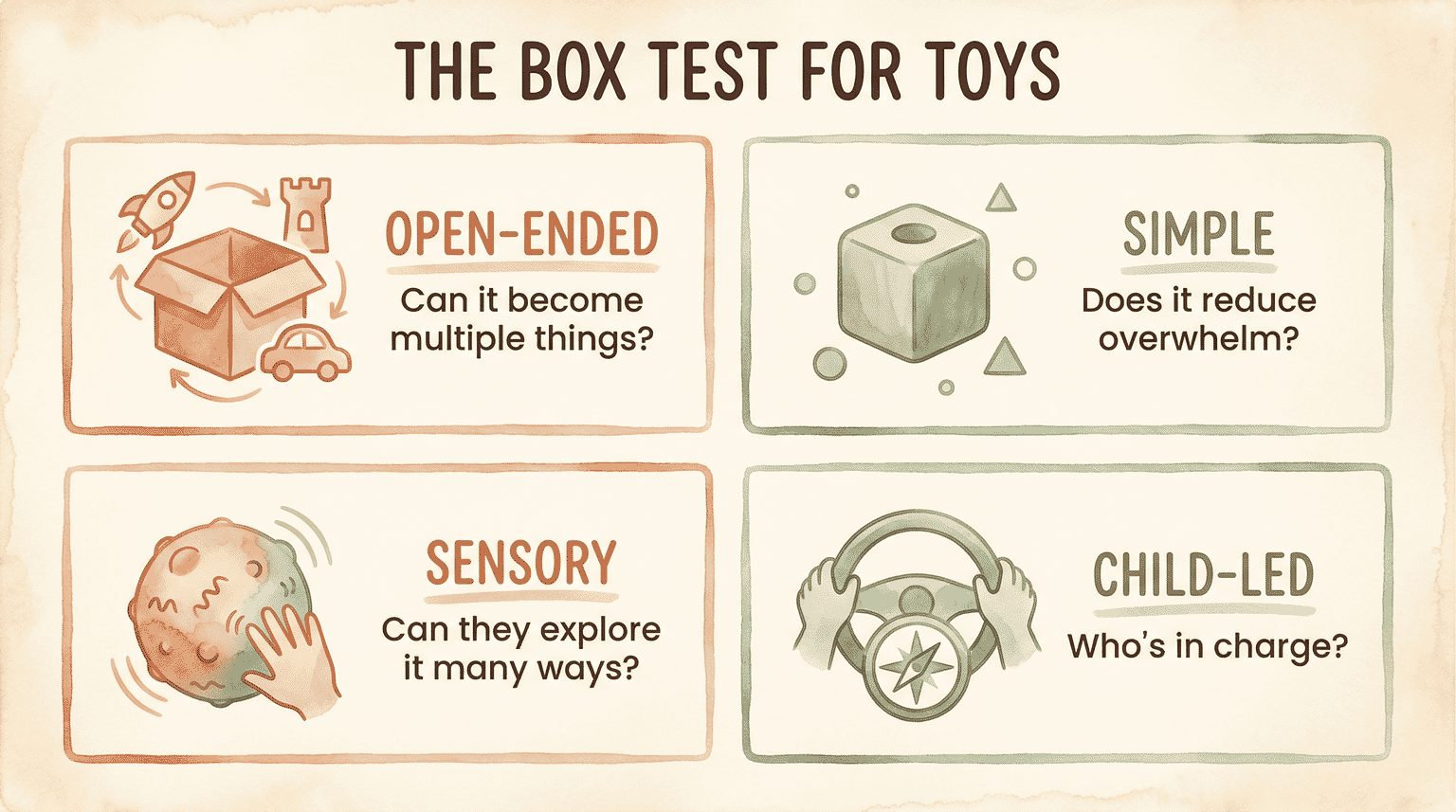

Understanding these four mechanisms can transform how you evaluate toys. Before your next purchase, ask:

- Can this become multiple things? (Open-ended test)

- Does this simplify or complicate the play environment? (Cognitive load test)

- Can my child manipulate this in multiple ways? (Sensory exploration test)

- Who’s in charge—my child or the toy? (Control test)

Toys that pass all four tests share “box principles”: blocks, play silks, wooden figures, balls, sand, and yes, actual cardboard boxes. These aren’t lesser toys—they’re developmentally rich materials that happen to cost less.

For deeper guidance on matching toys to your child’s specific developmental stage, I break down what works at each age in my guide to age-appropriate gift selection. And if you’re curious about the broader research on how children experience receiving gifts, I explore the science behind how children receive gifts in more detail there.

Reframing “Flighty” Behavior

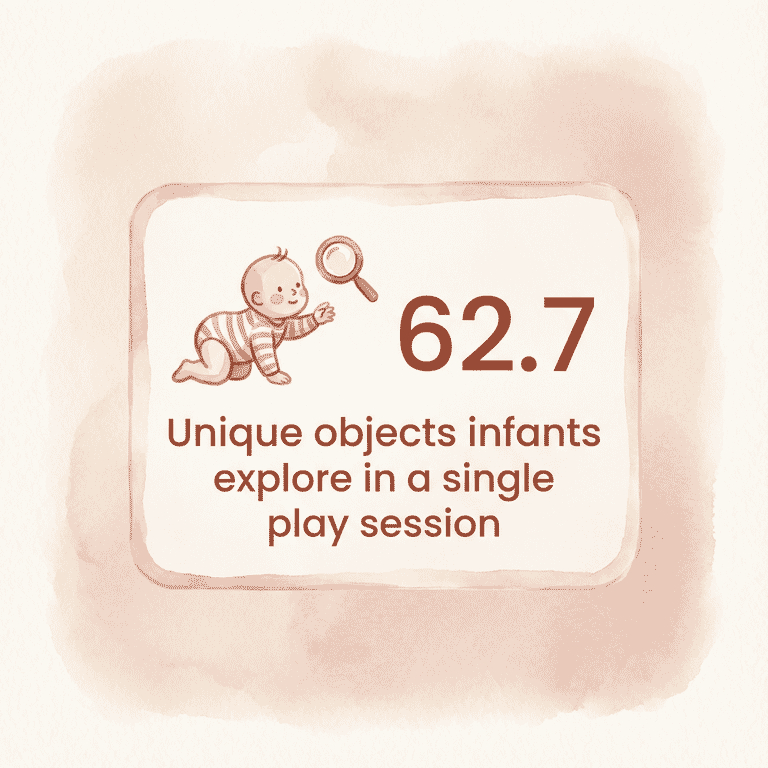

One more finding worth noting, because it addresses something that worries many parents: that NYU study found the median object interaction lasted just 9.8 seconds. That’s less than ten seconds before moving on.

That sounds like a problem, right? Short attention span? Can’t focus?

Here’s the reframe: during each observed session, infants engaged with an average of 62.7 unique objects. They weren’t flitting randomly—they were conducting comprehensive environmental research.

Brief, varied exploration is how toddlers build broad knowledge about how the world works. That rapid-fire curiosity is a feature, not a bug.

I’ve seen this play out with my own kids. The 2-year-old touches everything in a room within minutes. The 17-year-old can focus for hours. Both are doing exactly what their developmental stage requires.

Your toddler’s rapid-fire exploration is a feature, not a bug. And a simple box supports that exploration better than a complicated toy with only one “right” way to play.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does my toddler play with boxes instead of toys?

Boxes offer what developmental psychologists call “open-ended play”—unlimited possibilities that match toddlers’ cognitive development. The NYU study found infants spent nearly equal time with household items like boxes as with actual toys, confirming this preference is universal and developmentally appropriate.

Is it normal for babies to prefer boxes over expensive toys?

Completely normal. Research found 98% of infants played with boxes and baskets. Toddlers don’t distinguish between “toys” and “non-toys”—they’re drawn to objects that respond to their manipulation without limiting their creativity.

What can toddlers learn from playing with boxes?

Box play develops motor skills (climbing in and out), spatial reasoning (understanding inside, outside, and under), problem-solving (making it fit a purpose), and symbolic thinking (pretending it’s a car or house). Research shows children who engaged in complex object play showed improved mathematical outcomes years later.

Should I buy fewer toys for my toddler?

Research supports fewer toys for deeper play. Studies found infants played twice as long with each toy when given four versus twelve options. The average American home has 139 visible toys—far exceeding what toddlers can meaningfully engage with. Quality and open-ended design matter more than quantity.

I’m Curious

What’s the weirdest thing your toddler chose over an actual toy? I’ve got kids who’ve preferred wooden spoons, empty water bottles, and once—memorably—a colander worn as a helmet for an entire afternoon. The “reject the gift, love the packaging” moments are some of my favorite parenting stories.

I read every box story and they help other parents feel normal.

References

- Infant exuberant object play at home – NYU study on infant object interactions and play patterns

- How Many Toys Should Your Toddler Have? – Research on optimal toy quantities

- Putting things in and taking them out of containers – Developmental study on container play behaviors

- The Role of Play and Objects in Children’s Deep-Level Learning – Research on object manipulation and learning

- The Relationship Between Children’s Indoor Loose Parts Play and Cognitive Development – Study on open-ended materials and cognitive outcomes

- Cardboard Connections: Fostering project-based learning in preschool – Ohio State practical application research

Share Your Thoughts