Your four-year-old is melting down in Target because she can’t have the unicorn she spotted thirty seconds ago. Yesterday, it was a different unicorn. Tomorrow, it’ll be something else entirely. You’ve tried reasoning. You’ve tried distraction. You’ve tried the firm “no.” Nothing seems to stick.

Here’s what I wish someone had told me when my oldest (now 17) was deep in the gimme phase: this isn’t a character flaw you need to fix. It’s a brain still under construction.

My librarian brain couldn’t let this one go without digging into the research. After eight kids and more store meltdowns than I can count, I finally understand what’s actually happening in their heads—and why it’s not just normal, but exactly what their brains are supposed to be doing.

Key Takeaways

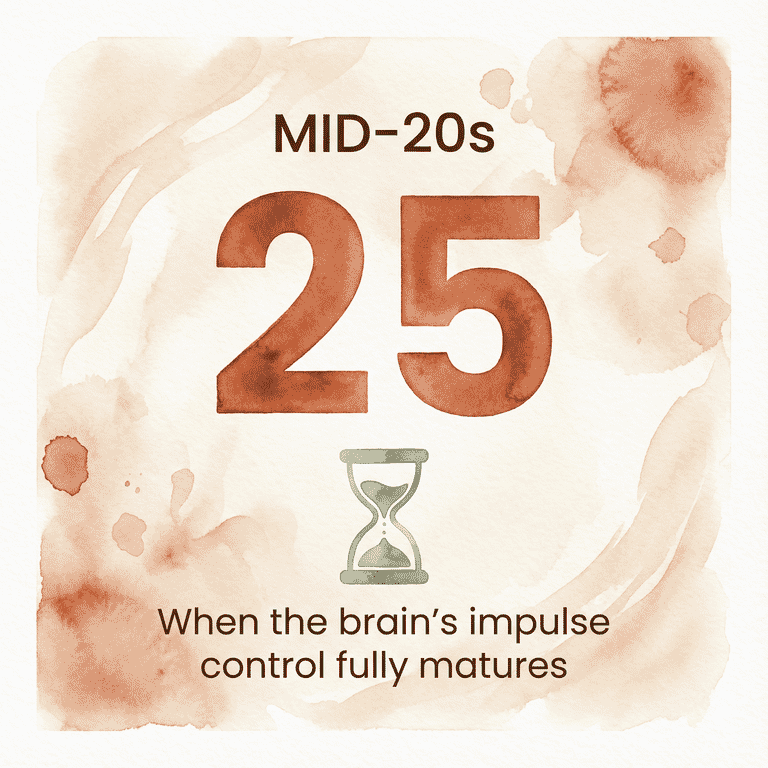

- Your child’s impulse control center (prefrontal cortex) won’t fully develop until their mid-twenties—the “gimmes” are biology, not bad behavior

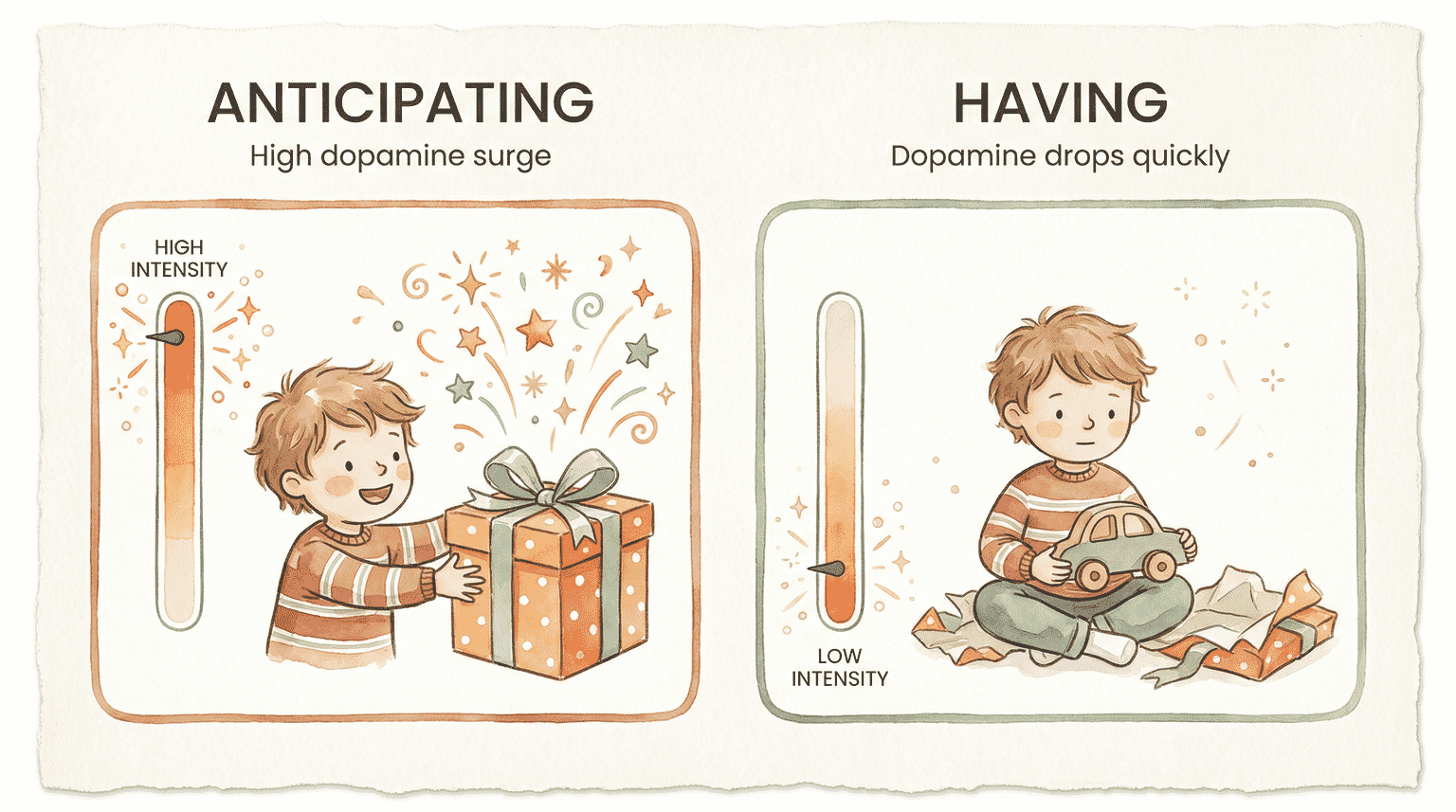

- The anticipation of getting something creates a bigger dopamine surge than actually having it, which explains why new toys lose appeal so fast

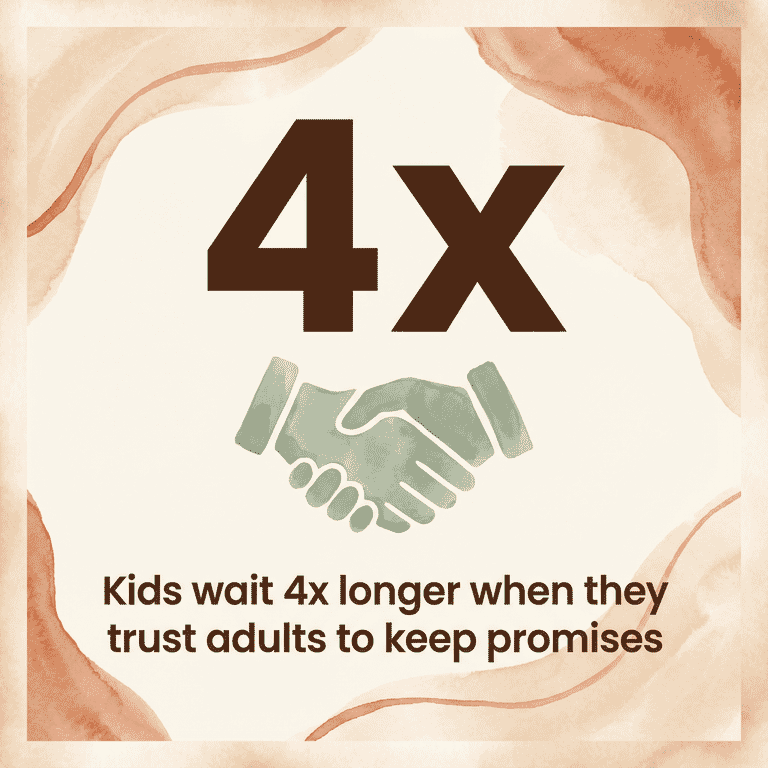

- Children who trust adults to keep promises wait up to 4x longer for rewards

- Distraction works because it gives the brain something else to do—hiding desired items nearly triples waiting time

- Letting children lead their own play actually builds self-regulation better than constant parental guidance

The Brain’s Wanting Machine

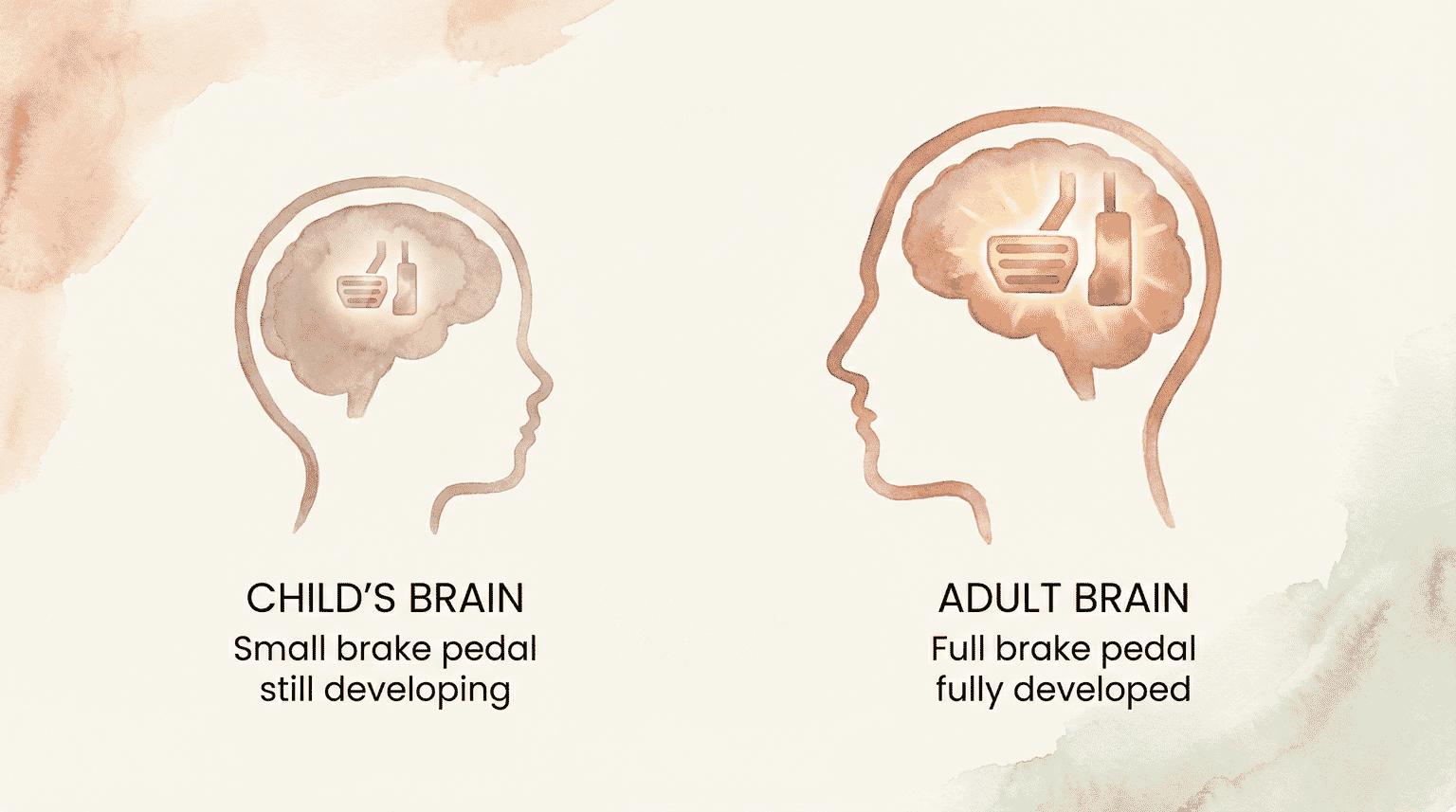

The part of your child’s brain responsible for impulse control is called the prefrontal cortex. Think of it as the brain’s brake pedal. Here’s the problem: that brake pedal doesn’t fully develop until the mid-twenties.

Yes, you read that correctly. Mid-twenties.

A 2021 review published through NIH examined how curiosity develops across childhood and adolescence. The researchers found that the prefrontal cortex shows “protracted maturation up to young adulthood.” In plain terms? Your child’s brain is working with an underpowered brake system for the next two decades.

But here’s what makes the gimme phase so intense in young children specifically: their filtering system hasn’t developed yet. The same NIH research found that children under 10 are “overall more likely to report higher curiosity rather than differentiating between information associated with high versus low curiosity.”

Translation? They want everything because their brain hasn’t yet learned to sort wants into categories like “really important” and “meh, maybe later.”

When my 4-year-old sees a toy, her brain responds with full intensity. When I see the same toy, my (theoretically) mature prefrontal cortex helps me filter: Do we need this? Where would it go? Is this just impulse? She doesn’t have that filter yet. Her wanting is unfiltered wanting.

This is why telling a young child to “just calm down” about something they want is like asking them to run a marathon on legs that are still growing. The neural equipment isn’t there yet.

Why Wanting Feels Better Than Getting

Here’s something that surprised me until I saw it confirmed in research: for kids (and honestly, for adults too), the anticipation of getting something often creates a bigger brain response than actually getting it.

This is the dopamine factor at work.

Dopamine—the brain’s reward chemical—surges during anticipation. The wanting stage lights up reward pathways in ways that having often doesn’t match. This explains something every parent has witnessed: your child desperately wants a toy, finally gets it, and loses interest within hours.

It’s not ingratitude. It’s brain chemistry doing exactly what it evolved to do.

The novelty factor amplifies this. Young children’s brains are wired to seek new experiences—it’s how they learn about the world. That shiny new thing in the store represents novelty, possibility, the thrill of something unknown. Once they have it? The novelty wears off. The dopamine drops. They’re ready for the next new thing.

This same mechanism explains why unboxing videos are so compelling to children. Watching someone else open packages triggers that same anticipation response. The viewing is the dopamine hit.

If you’ve ever wondered why your child checks the package tracking obsessively or why the wait for a birthday feels interminable to them, this is why. Their brains are swimming in anticipation chemicals, making the waiting both exciting and almost unbearable.

What the “Gimme” Is Actually Saying

Not every “I want that” is about the thing itself.

Research from Indiana University School of Medicine highlights something important: children will do things to get parental attention, and they don’t particularly care whether that attention is positive or negative. Dr. Christine Raches puts it clearly: “Children want and desire their parents’ attention and will do things to get it.”

Sometimes the gimmes are actually bids for connection disguised as requests for stuff.

I’ve seen this with my own kids. The 6-year-old asking for the fourteenth snack isn’t hungry—she’s noticed I’ve been on the phone for an hour. The 4-year-old demanding a toy at the store often settles down remarkably fast when I get down on her level and give her my full attention.

The research suggests that when positive behaviors receive more attention than negative ones, the negative behaviors diminish. Dr. Raches recommends 15 minutes daily of child-led one-on-one interaction—letting them lead the activity while showing that their interests matter.

Trust also plays a role in how children manage wanting. A fascinating replication of the famous marshmallow experiment at the University of Rochester found that kids who had experienced reliable adults—people who kept their promises—waited up to four times longer for rewards than kids who’d been given broken promises.

When a child has learned that adults follow through, they’re better equipped to wait. When they’ve learned that promises are unreliable, their brain essentially says: grab it now, because later might not come.

This finding shifted how I think about consistency. Every kept promise is a deposit in the trust bank that helps kids delay gratification later.

Why Some Kids Struggle More Than Others

If you have multiple children, you’ve probably noticed they handle wanting differently. My 8-year-old can wait for things relatively well. My 4-year-old acts like waiting might actually cause physical pain.

Research confirms this isn’t just personality—there’s a genetic component.

A 2021 study in the Journal of Child and Family Studies found that the heritability of delay discounting (how much someone devalues future rewards) is approximately 40% at age 16 and increases to 60% by age 18. Some children are simply wired to find waiting harder than others.

But here’s the reassuring part: environment matters enormously too.

The same study found that parental warmth, responsiveness, and autonomy support all contribute to self-regulation development. Positive parenting—supporting children’s independence while remaining warm and responsive—correlates with better executive function and self-control.

The willpower narrative is incomplete. A 2018 replication of the classic marshmallow experiment found that the original effect was only half as strong in a larger, more diverse sample. Economic background explained significant variance that the original study missed. Some children wait more easily because they’ve had more practice waiting in safe environments—not because they have superior character.

This matters because it shifts the question from “How do I fix my child’s lack of self-control?” to “How do I create conditions where self-control can develop?”

Why Distraction Actually Works

Every parent has tried distraction. But do you know why it works?

The original marshmallow experiments from the 1970s revealed something important: children who successfully waited didn’t do it through willpower alone. They did it through cognitive avoidance. The kids who waited longest covered their eyes, sang songs to themselves, invented games, or even tried to fall asleep—anything to avoid focusing on the treat.

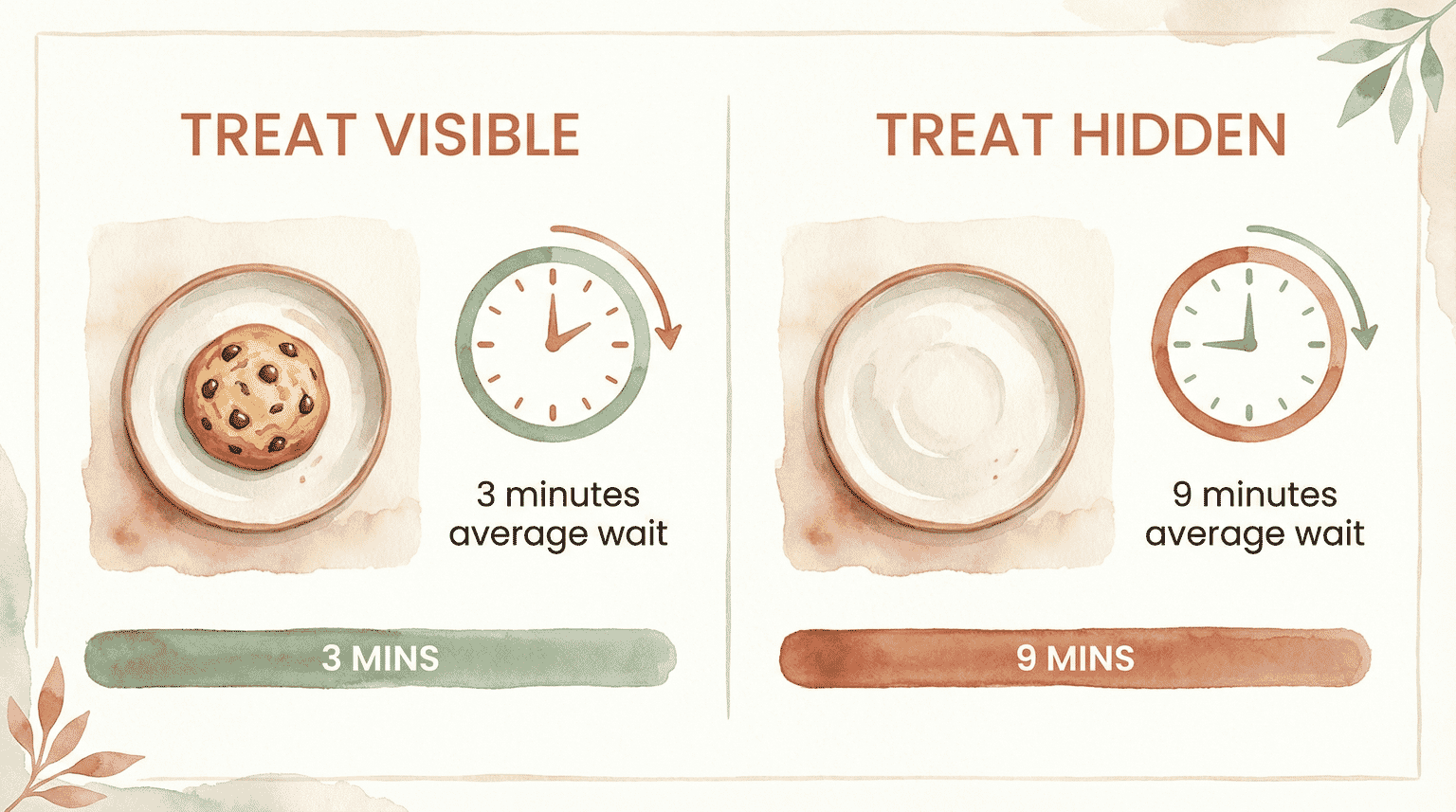

When treats were visible, children waited an average of 3.09 minutes. When treats were hidden, they waited 8.9 minutes—nearly three times longer.

Seeing the desired thing makes waiting exponentially harder. This is why removing the temptation from sight often works better than any amount of reasoning.

A 2023 study in the Journal of Experimental Child Psychology took this further, identifying three distinct patterns in how children manage temptation:

- Passive children showed low fidgeting and vocalizations with moderate anticipation

- Active children displayed moderate fidgeting and vocalizations with high anticipation

- Disruptive children exhibited high fidgeting, vocalizations, and anticipation

The critical finding? Children in the Passive group were 1.5 times more likely to successfully wait compared to Active children. Moderate activity levels, not extreme stillness or extreme movement, seemed most beneficial.

The researchers explained that self-control requires “inhibiting an impulsive response in order to activate a more appropriate one.” This takes real cognitive effort—recruiting the brain’s executive functions to override the impulse. For a young child with limited executive function capacity, this is genuinely hard work.

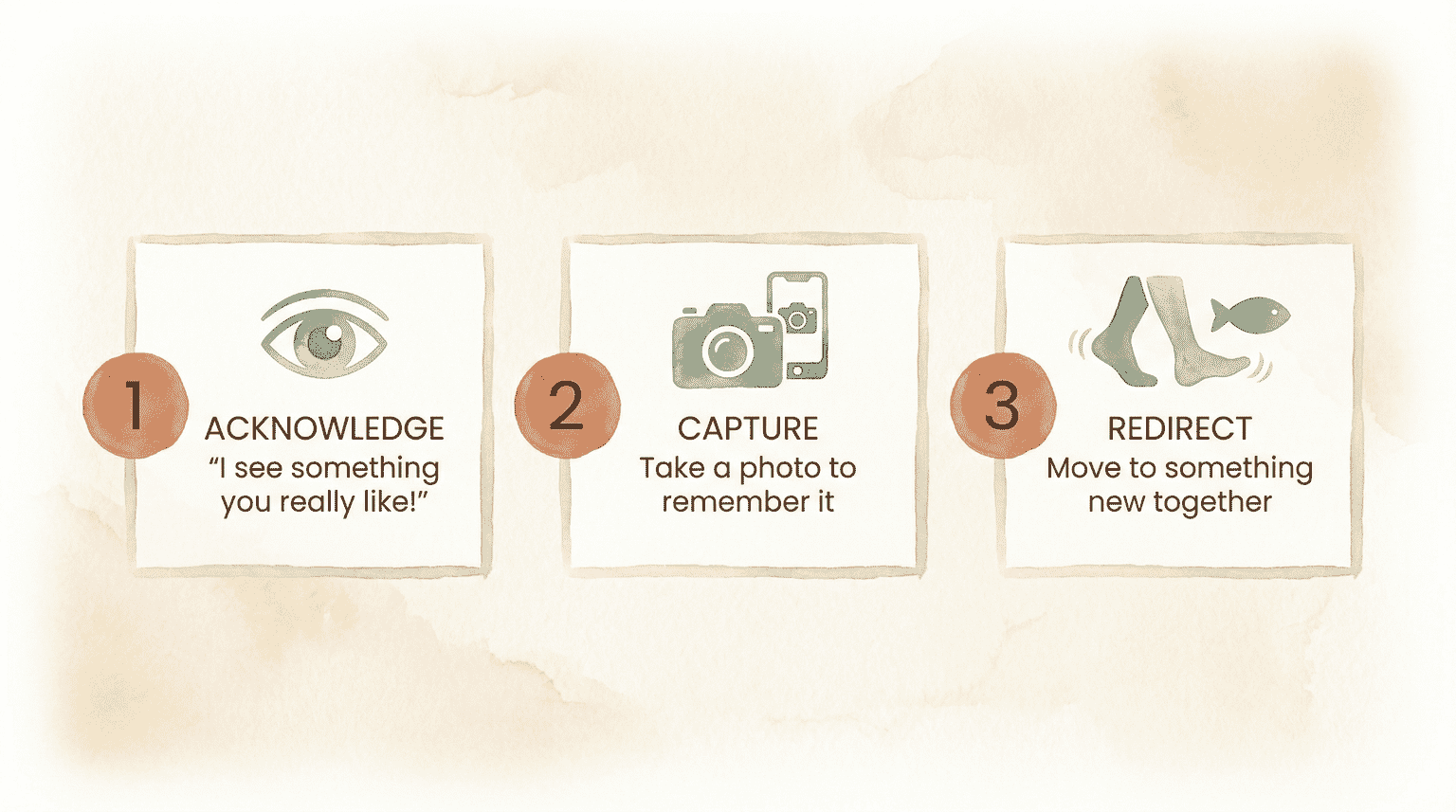

When your child says: “I want that toy NOW!”

Try: “I see something you really like! Let’s take a picture so we remember it, and then let’s go look at the fish tank over there.”

The redirection isn’t about dismissing their feelings—it’s about giving their brain something else to do besides fixating on the want.

This approach validates the feeling while physically moving attention elsewhere. And honestly? Taking a photo of the wanted item has saved me from countless meltdowns. It acknowledges the want without giving in to it.

Building the Brake Pedal

Here’s where the research gets counterintuitive.

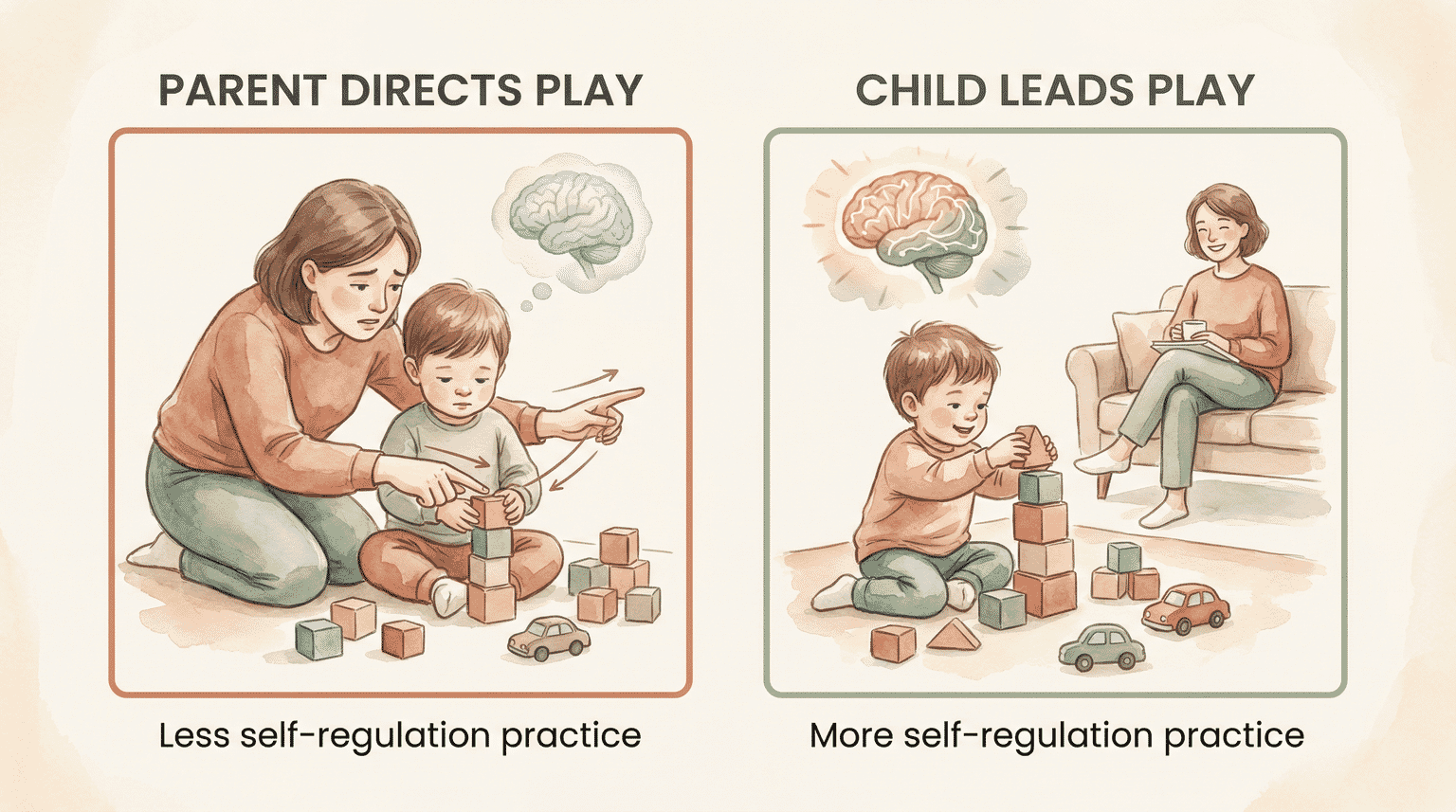

A 2021 Stanford study found something that surprised the researchers themselves. Children whose parents frequently stepped in during play—offering suggestions, corrections, and help even when kids were doing fine—actually showed worse self-regulation abilities. These children also performed worse on delayed gratification tasks.

Professor Jelena Obradović explained the mechanism: “Parents have been conditioned to find ways to involve themselves, even when kids are on task and actively playing or doing what they’ve been asked to do. But too much direct engagement can come at a cost to kids’ abilities to control their own attention, behavior and emotions.”

When we let children take the lead, they practice self-regulation. They build that brake pedal through use.

This doesn’t mean abandoning children to figure everything out alone. The study clarified that there’s no harm in stepping in when children are off-task, breaking rules, or only half-heartedly engaged. The key is recognizing when they’re managing fine and resisting the urge to “help.”

For understanding the science of how children experience gifts, this research has real implications. The child who opens a gift and plays with it independently—even imperfectly—is building self-regulation muscles. The parent hovering with suggestions might actually be interrupting that development.

When Wanting Becomes Concerning

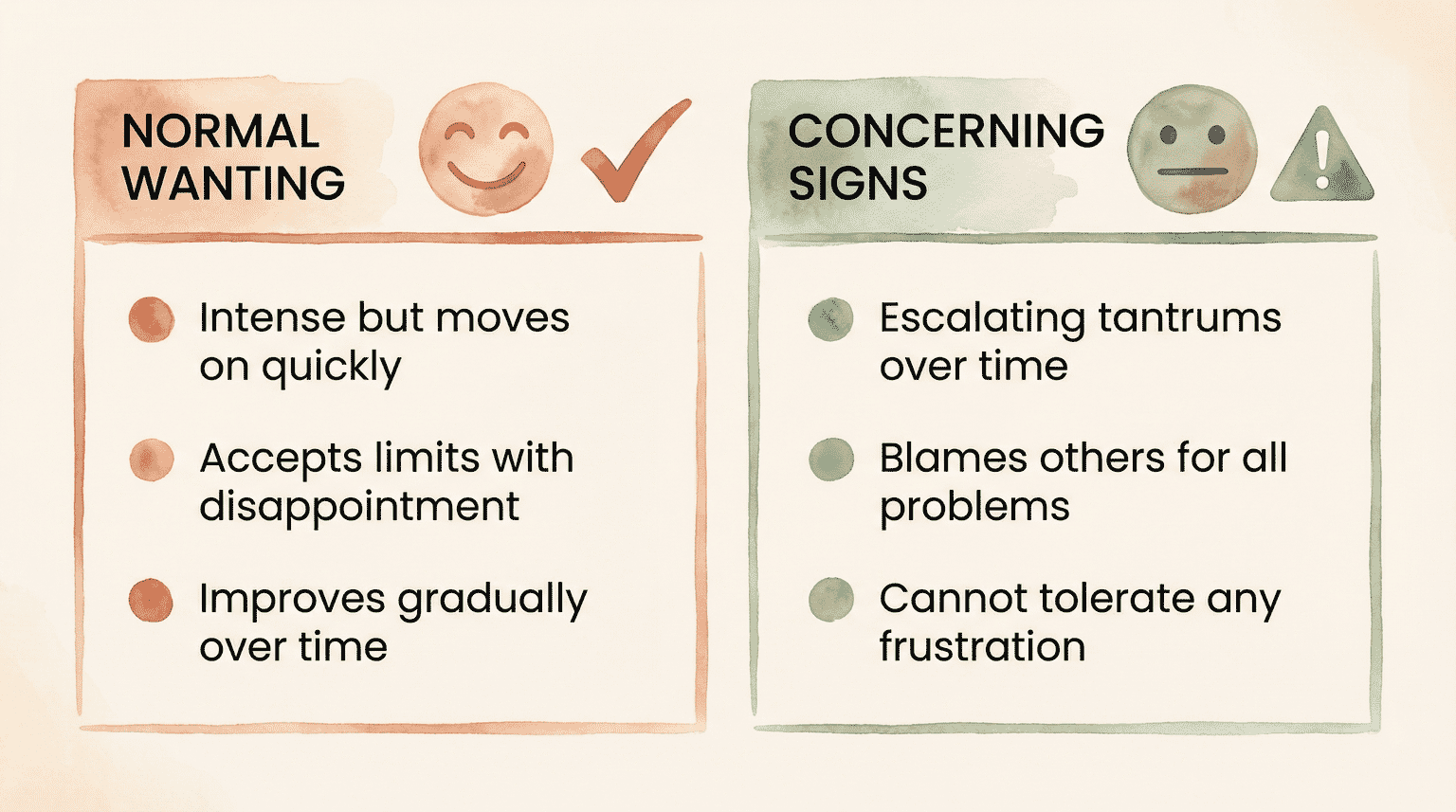

Normal developmental wanting looks like: wanting lots of things intensely but moving on relatively quickly, accepting limits with disappointment but not destruction, and gradually improving at waiting over months and years.

Pepperdine psychologist Michael G. Wetter distinguishes between normal wanting and entitled behavior. Entitlement isn’t just wanting things—it’s “the expectation of instant gratification” combined with believing rules don’t apply to them and seeing only their own needs as important.

Some red flags by age:

- Toddlers: Some demanding behavior is completely normal. Concern arises when tantrums escalate rather than gradually improving over time

- Middle schoolers: Blaming others (teachers, friends) for all problems rather than taking any accountability

- Teenagers: Deep discomfort with any frustration, combined with “everyone else has one” as primary reasoning

Dr. Wetter notes that “the attitude of entitlement is in many ways an effort to avoid adversity, difficulty, and challenge.” Children need opportunities to experience not getting what they want—and discovering they can survive that disappointment.

For practical guidance on breaking the cycle of constant wanting, the research suggests that gratitude develops when children don’t get everything they ask for. Allowing them to want without immediately satisfying builds the very capacity that prevents entitlement.

The Bottom Line

Standing in the store while your child loses it over a toy they’ll forget by tomorrow is exhausting. I’ve lived it with eight kids across seventeen years.

But here’s what the research has taught me: that desperate wanting comes from a brain doing exactly what it’s supposed to do. The prefrontal cortex is under construction. The dopamine system is working overtime on novelty. The filtering mechanism that will eventually say “I don’t actually need that” is still years from completion.

This doesn’t mean you give in to every demand. It means you stop interpreting the gimmes as a failure—yours or theirs.

When you understand what’s happening in your child’s brain, you can respond with strategies that actually work: redirect attention rather than argue logic, remove visible temptations when possible, provide practice opportunities for waiting in low-stakes situations, and perhaps most importantly, step back when they’re managing okay on their own.

The brake pedal is coming. It just takes longer than any of us would like.

For parents wondering about practical applications—like determining the right number of gifts for birthdays and holidays—understanding this brain science can actually guide those decisions. Sometimes fewer gifts, with more anticipation built in, creates more satisfaction than an overwhelming pile.

Because ultimately, what we’re helping our children build isn’t the ability to never want things. It’s the capacity to want things and tolerate not getting them immediately. And that capacity develops through practice, patience, and a whole lot of grace—for them and for ourselves.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does my child want everything they see?

Your child’s prefrontal cortex—the brain’s impulse control center—won’t fully mature until their mid-twenties. NIH research confirms this “protracted development” creates an inherent bias toward curiosity in early childhood. Young children’s brains respond intensely to novelty without the filtering mechanisms that help adults distinguish important wants from passing impulses.

At what age can kids control their impulses?

Impulse control develops gradually throughout childhood and adolescence, with meaningful improvements typically visible between ages 4-6 and continued development through the teenage years. Research shows children’s delay of gratification ability improves steadily with age, though significant individual variation exists based on temperament, environment, and practice opportunities.

Is it normal for toddlers to want everything?

Yes—this is developmentally expected behavior. Toddler brains are wired to explore and seek novelty, while the neural systems for impulse control remain largely undeveloped. Intense wanting behaviors reflect biology, not character flaws or parenting failures.

How do I stop my child from wanting everything?

Rather than eliminating wanting (which is developmentally normal), help your child build their brain’s self-regulation capacity over time. Research shows distraction strategies work because they shift attention away from the reward. A 2023 study found children who redirected their own attention waited significantly longer than those focused on what they wanted.

Why can’t my child wait for things?

Waiting requires the prefrontal cortex to override the brain’s immediate reward signals—and this brain region develops slowly throughout childhood. For young children, the neural pathway that enables waiting is still under construction, making patience genuinely difficult rather than a choice they’re making to be difficult.

Over to You

What’s your go-to move when “the gimmes” hit in the middle of a store? I’ve tried everything from distraction snacks to the “put it on your birthday list” redirect—some worked, some spectacularly failed. What’s actually worked in your house?

I read every response—your store survival strategies help so many parents.

References

- Curiosity in Childhood and Adolescence — What Can We Learn from the Brain – NIH review on prefrontal cortex development and curiosity across childhood

- Stanford-Led Study Highlights the Importance of Letting Kids Take the Lead – Research on parent-child interaction and self-regulation development

- What Children Do While They Wait – 2023 study on self-control strategies in delaying gratification

- Entitled Children: Strategies for Improving Behavior – Pepperdine research on distinguishing normal wanting from entitlement

- Child Development — The Importance of Positive Attention – Indiana University School of Medicine research on attention and behavior

- Relationship Between Parental Big Five and Children’s Delay of Gratification – Study on genetic and environmental factors in self-control development

Share Your Thoughts