Your 4-year-old just ripped through the wrapping paper, found concert tickets inside, and looked at you with genuine confusion. “But where’s my present?” Meanwhile, the $10 plastic dinosaur from grandma? That’s coming to dinner, to bed, and apparently to the bathroom.

Here’s the thing: your child isn’t being ungrateful. Their brain is doing exactly what it’s supposed to do.

My librarian brain couldn’t let this one go. After watching eight kids react to gifts over the years—and after one particularly bewildering Christmas when my then-5-year-old burst into tears over what I thought was an amazing zoo membership—I dove into the research. What I found changed how I think about every gift I give.

Young children prefer toys over experiences because of three cognitive mechanisms—but this changes with age. : their memory systems can’t preserve experiences well enough to extract lasting happiness, they learn primarily through physical manipulation (spending 50%+ of waking hours handling objects), and they think concretely—a future trip doesn’t “exist” the way a present toy does.

Let me break down each mechanism, because understanding the why makes everything else click.

Key Takeaways

- Children ages 3-5 prefer toys because their memory systems can’t preserve experience happiness the way adults’ can

- Toddlers spend 50%+ of waking hours manipulating objects—it’s how they learn, and toys deliver this while experiences don’t

- The full preference flip to experiences happens around ages 13-17 when abstract thinking and memory mature

- Photos and physical mementos can make experiences “real” for young children who think concretely

- Your child’s toy preference isn’t a character flaw—it’s three brain mechanisms working exactly as designed

The Memory Mechanism: Why Experiences Slip Away

Why does that trip to the zoo fade while the $15 toy stays special?

It comes down to how young brains store happiness. According to University of Illinois Chicago research, children ages 3-5 appreciate material items more than experiences, while the preference completely flips by ages 13-17. The key factor isn’t preference—it’s memory capacity.

The research pinpoints a specific developmental window where toy preference peaks. It’s not about being materialistic—it’s about what young brains can actually process and retain.

This preference isn’t random or learned. It reflects the fundamental architecture of how children’s memory systems develop during these critical years.

“For experiences to provide enduring happiness, children must be able to recall details of the event long after it is over. At this stage, a child’s memory is not fully developed, so they have a harder time comprehending, interpreting and remembering events.”

— Dr. Lan Nguyen Chaplin, University of Illinois Chicago

Think about what an experience requires: your child has to encode the memory, store it properly, retrieve it later, and then extract emotional satisfaction from the recall. That’s a lot of cognitive steps for a brain still under construction.

Now think about what a toy requires: it’s there. Tomorrow it’s still there. Your child can return to it and get another hit of happiness every single time.

This is why my 4-year-old still talks about the stuffed owl she got last Christmas but has completely forgotten the children’s museum trip we took three months ago. The owl provides repeated bursts of joy. The museum trip required memory skills she doesn’t fully have yet.

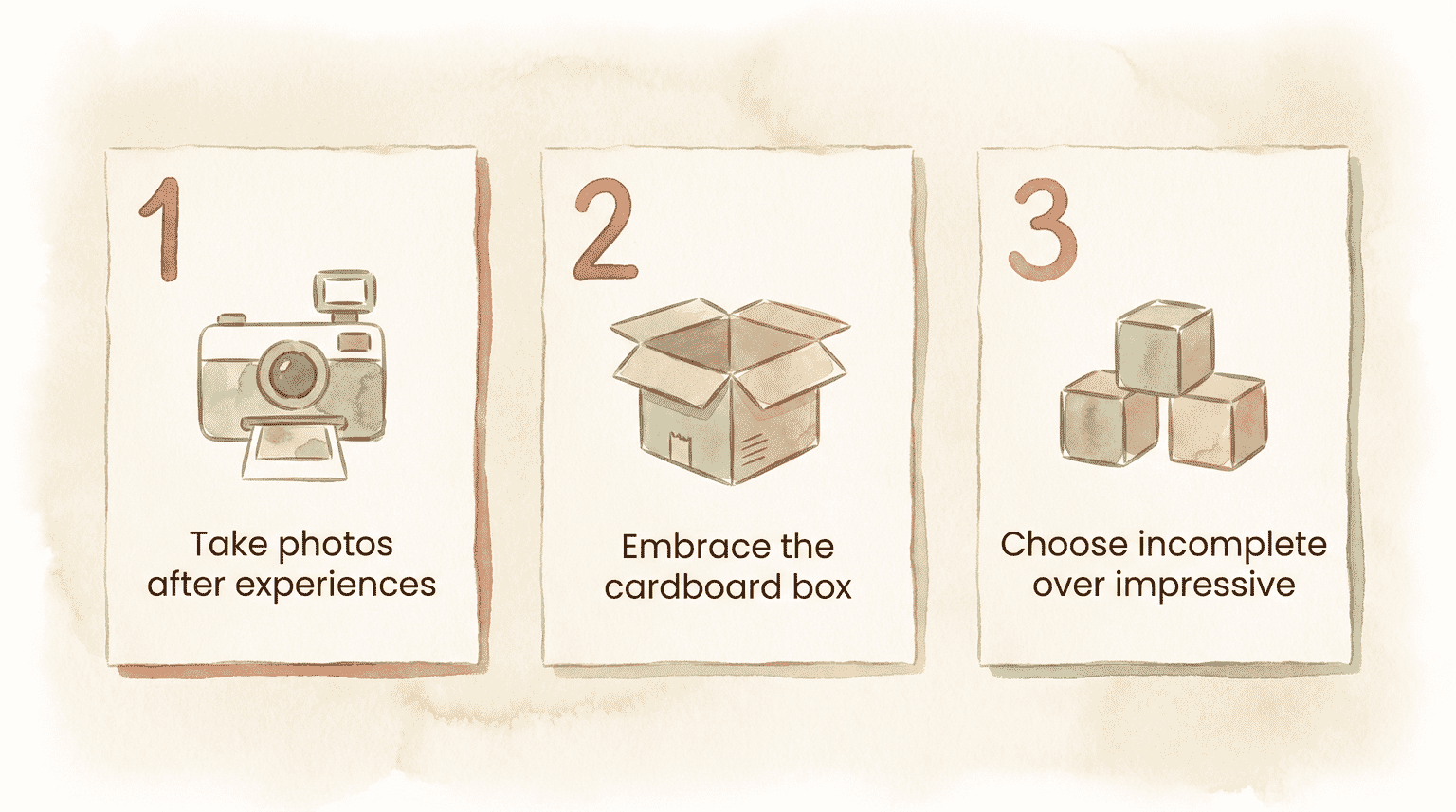

The researchers suggest one workaround: photos. Physical reminders help young children access experience memories they otherwise couldn’t retrieve. If you’re giving experiences to young kids, the photo book afterward might be more valuable than the experience itself. For more on this, check out our guide to gifts children actually remember.

The Manipulation Mechanism: Why Half Their Day Involves Touching Things

What does a cardboard box have that an expensive experience doesn’t? Handles they can grab, flaps they can fold, surfaces they can draw on, and endless possibilities for manipulation.

Dr. Catherine Tamis-LeMonda’s 900-hour observational study at NYU revealed something that shifted my understanding completely: even in homes filled with toys, infants spend just as much time playing with everyday objects—boxes, cups, cabinets—as with manufactured toys.

“So many of our models and theories about how children learn are based on data from very brief prestructured lab tasks, but if you watch kids play at home, you realize they’re often more interested in digging around in the houseplants and messing with the remote control.”

— Dr. Catherine Tamis-LeMonda, NYU

Research confirms that infants spend more than half their waking hours manipulating objects. This isn’t random fidgeting—it’s how they learn.

Each physical interaction builds neural pathways. Every grab, twist, and exploration teaches something new about how the world works.

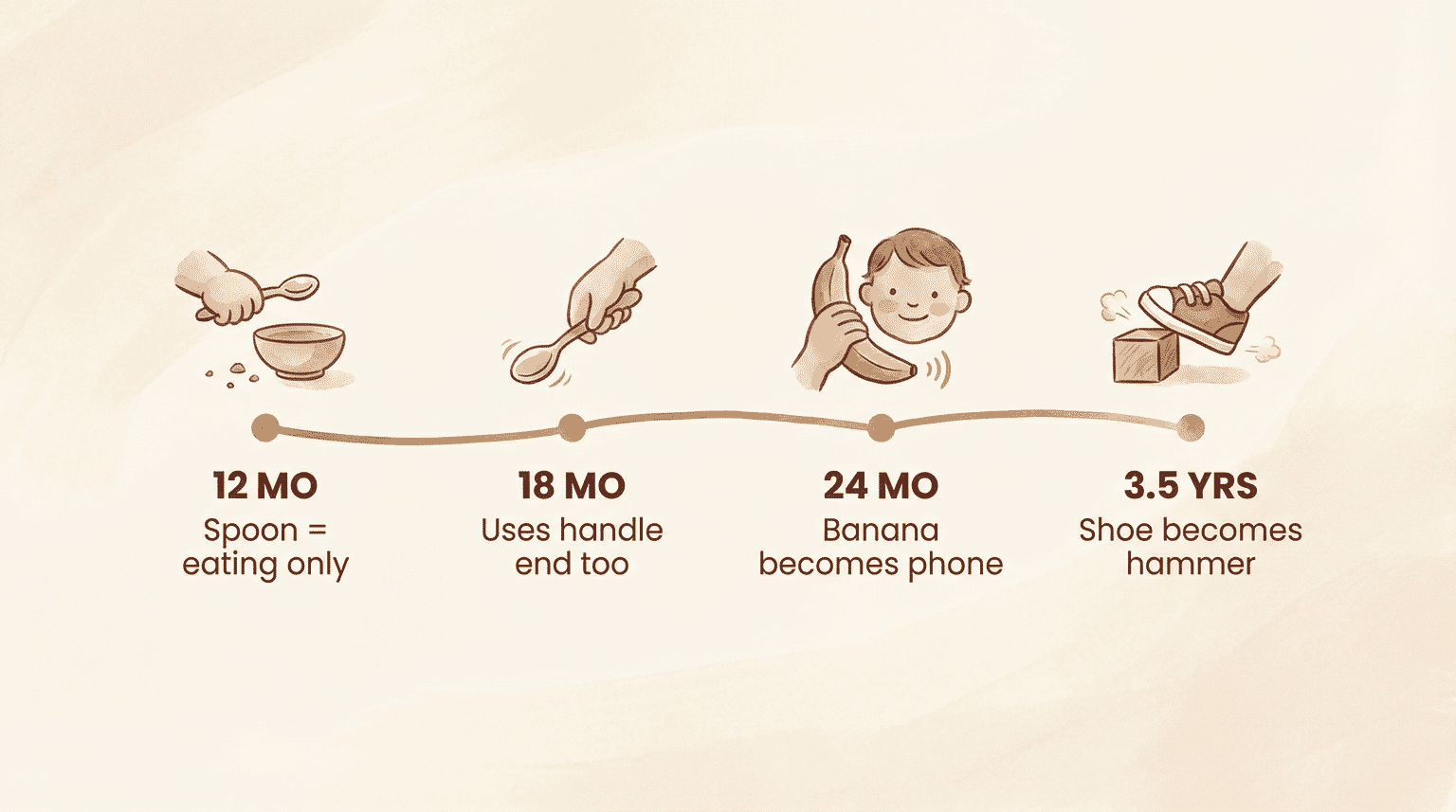

The developmental progression is fascinating:

- 12 months: Functional fixedness (a spoon is only for eating)

- 18 months: Beginning flexibility (can use the handle end of a spoon)

- 24 months: Object substitutions emerge (a banana becomes a phone)

- 3.5 years: Dramatic substitutions (a shoe becomes a hammer)

Each stage requires physical practice with real objects. Experiences, by definition, offer fewer opportunities for this kind of manipulation. You can’t grab a concert and bend it. You can’t take a trip apart and put it back together.

I’ve watched this in my own house. My 2-year-old will spend 45 minutes opening and closing a cardboard box, putting things in, taking them out, wearing it as a hat. The developmental work happening in that moment is exactly what her brain is hungry for.

The Concrete Thinking Mechanism: Why “We’ll Go to the Zoo” Doesn’t Compute

Try explaining to a 4-year-old that they’re getting “a trip to Disneyland in three months.” Watch their face. They’re not ungrateful—they genuinely can’t process what you’re offering.

Developmental psychologists have long documented that children under age 7 think in concrete, not abstract terms. Piaget called ages 2-7 the “preoperational period”—children at this stage are egocentric, symbolic, and bound to the concrete present. “Future happiness” is an abstract concept that doesn’t register the way a physical toy does.

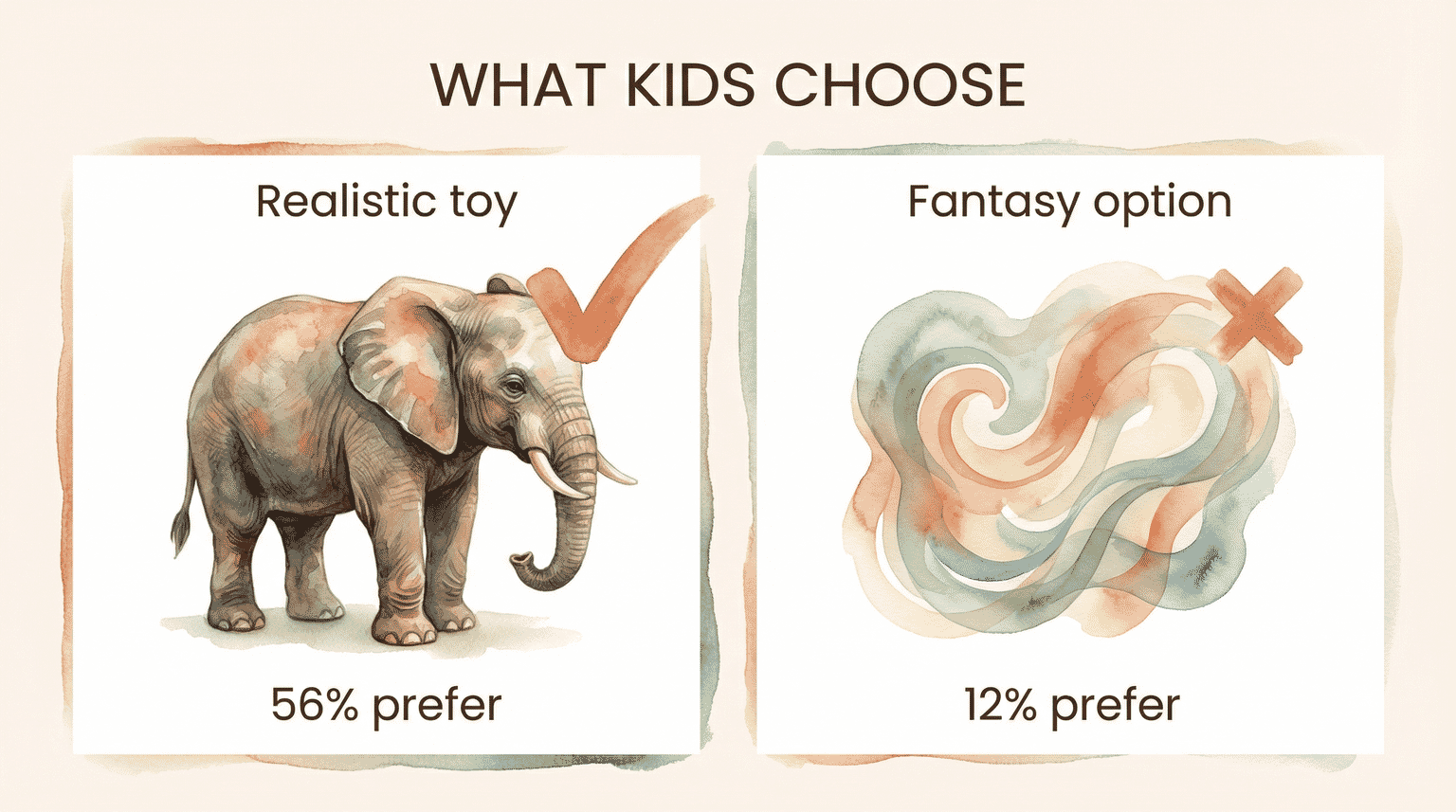

A 2023 study of 129 preschoolers found that 55.8% of children chose the most realistic toy when given options, while only 12.4% selected fantasy options. Similarly, 63.6% preferred the most detailed toy. Why? Realistic, detailed toys map to concrete, known reality. Children can mentally manipulate them because they’re comprehensible.

Here’s what struck me most: the researchers found no relationship between intelligence, executive function, or emotional understanding and these preferences. Smart kids and average kids showed the same patterns. It’s not about cognitive ability—it’s about developmental stage. Every child’s brain works this way at this age.

A trip to the zoo is an abstract future event. A toy elephant is concrete reality right now. For a brain that can’t reliably project into the future, the choice is obvious.

The Articulation Gap: Why Kids Can Explain Toys But Not Experiences

Here’s a detail that changed how I approach gift discussions with my younger kids.

A 2023 study examining how children explain their toy choices found a clear pattern. Children selecting realistic toys gave play-focused explanations with well-defined ideas:

- “I would play doctor.”

- “I will sell toys and some fruit.”

- “I often go to the shop with my mum, want to play in it.”

Children choosing trendy or abstract items gave appearance-focused explanations with uncertain motivation:

- “Because it is cute.”

- “Because it has sharp teeth and big eyes.”

- “Because I have one at home.”

The researchers characterized this as “empty” motivation—children don’t understand what they’ll actually do with abstract choices.

Apply this to experiences: when you ask a young child if they’d rather have a toy truck or a trip to the aquarium, they can clearly imagine playing with the truck. The aquarium? That’s vague, uncertain, impossible to mentally manipulate.

This isn’t stubbornness or poor decision-making. It’s cognitive limitation. Asking young children to choose between toys and experiences isn’t a fair comparison—their brains can’t evaluate both options equally.

When the Shift Actually Happens

The UIC research found the full preference flip occurs around ages 13-17, when teenagers consistently prefer experiences over material items. But the transition is gradual, not sudden.

The teenage brain finally has the architecture to make experiences valuable. Memory systems work reliably. Abstract thinking clicks into place.

This is when concert tickets, travel experiences, and adventure gifts start winning over physical objects.

What changes?

- Memory capacity matures: Teens can encode, store, and retrieve experience memories effectively

- Abstract thinking develops: Future events become “real” in ways they weren’t before

- Social value recognition emerges: Experiences gain worth partly because they’re shareable stories

I see this playing out with my 15 and 17-year-olds. They genuinely prefer concert tickets to most physical gifts now—and they can articulate exactly why. My 10-year-old is somewhere in the middle. My 4-year-old? Still Team Toy, as her brain intended.

For a complete age-by-age guide to gift preferences and when each transition typically occurs, I’ve mapped out what to expect at each developmental stage.

What This Means for Your Gift-Giving

Understanding these mechanisms doesn’t mean you should never give young children experiences. It means you should work with their developmental stage rather than against it.

Make experiences tangible. Physical tickets, countdown calendars, photo books afterward—these create the concrete anchors young brains need. The Child Mind Institute notes that ages 3-5 are the “high season” of imaginative play, and realistic props help children engage. Apply this to experiences: a stuffed animal from the zoo gift shop might make the trip “real” in ways the trip itself couldn’t.

Embrace the cardboard box. As Dr. Barry Kudrowitz from the University of Minnesota observed: “We actually have a box in our dining room right now from a couch, but it’s been played with by the children for months now. It’s a fort, it’s a rocket ship, they’re drawing all over the walls. And that was free, and it’s compostable.”

Choose incomplete over impressive. Dr. Doris Bergen’s insight has guided my gift-giving for years: “A really good toy is one that doesn’t do everything itself, but has the child do it.” Toys that require child input—imagination, manipulation, problem-solving—provide deeper engagement than impressive toys that perform on their own.

Stop feeling guilty. Your toddler’s preference for the $8 toy over the $80 experience isn’t a character flaw you created. It’s three brain mechanisms working exactly as designed. For strategies on making experiences tangible for young children, or to find experience gifts that actually work for children at various ages, we’ve compiled research-backed approaches.

The research has genuinely changed how I approach gifts for my youngest three. I’ve stopped trying to convince them that experiences are “better.” Instead, I meet them where they are—with physical objects they can touch, manipulate, and return to tomorrow.

And honestly? Watching my 2-year-old’s face light up over a simple wooden stacking toy is just as magical as watching my 17-year-old react to concert tickets. Different developmental stages, different cognitive needs, same goal: a gift that actually lands.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do toddlers prefer toys?

Toddlers prefer toys because their brains are wired for physical manipulation—research shows infants spend more than half their waking hours handling objects. A toy provides immediate, tangible interaction they can return to repeatedly, while experiences offer no physical component to grasp, manipulate, or revisit.

At what age do children start preferring experiences over gifts?

Research from the University of Illinois Chicago found that the full shift to preferring experiences occurs around ages 13-17, when memory systems mature and abstract thinking develops. The transition is gradual—it typically begins around ages 7-8 when children can anticipate future events and understand that experiences have lasting emotional value.

Are experiences better than toys for kids?

Neither is universally “better”—it depends on the child’s developmental stage. For children under 5, toys are developmentally appropriate because they match how young brains learn (through physical manipulation) and remember (through concrete, present objects). For tweens and teens, experiences become more valuable because their mature memory systems can preserve the emotional benefits.

Why do kids want so many toys?

Children want toys because each one represents a new manipulation opportunity—and physical manipulation is how young children learn. A 2023 study found that children prefer realistic, detailed toys because they can clearly imagine play scenarios with them. It’s not greed; it’s a developmental drive to interact with the physical world.

I’m Curious

Have your kids reacted differently to toys vs. experience gifts? I’d love to hear at what age the shift happened—or whether some of your kids still prefer unwrapping something physical every time.

Your stories help me understand how this plays out across different families.

References

- University of Illinois Chicago Research via CNBC – Memory development and gift appreciation in children

- NYU Steinhardt PLAY Study – 900-hour observational study of infant object manipulation

- Psychology in Russia: Toy Preferences Study – Research on why children prefer realistic, detailed toys

- PMC: Young Children’s Interactions with Objects – Developmental progression of object play

- PMC: Executive Function and Toy Choice – How children explain their toy preferences

- Child Mind Institute: The Power of Pretend Play – Developmental timeline for imaginative play

- APA: Psychology Takes Toys Seriously – Expert perspectives on toy design and child engagement

Share Your Thoughts