Your child is transfixed. Again. Someone they’ve never met is slowly peeling tape off a cardboard box, and your kid is watching like it contains the secrets of the universe. You’ve tried interrupting. You’ve offered actual toys—toys they own, sitting right there. Nothing competes.

Here’s the thing: this isn’t random. When I first noticed my then-4-year-old ignoring her brand-new birthday presents to watch a stranger unwrap LOL Dolls, my librarian brain kicked in. There had to be research explaining this.

Turns out, there’s a lot—and understanding it changes how you see these videos (and what you do about them).

Key Takeaways

- Children under 7 experience unboxing videos as wish fulfillment—their brains can’t fully distinguish watching from experiencing

- The slow unwrapping structure triggers dopamine rewards during anticipation, not just at the reveal

- Kids form genuine-feeling friendships with YouTubers they’ve never met—and fewer than half can identify these videos as ads

- Co-viewing and asking questions builds media literacy more effectively than bans alone

The Six Reasons Kids Can’t Look Away

Why kids love unboxing videos:

- Wish fulfillment that feels real to their developing brains

- Anticipation-and-reveal loops that trigger dopamine rewards

- Parasocial bonds with hosts they perceive as actual friends

- Algorithm recommendations that keep similar content flowing

- Sensory satisfaction from sounds and textures (ASMR elements)

- Identity exploration through watching others discover “their things”

These aren’t separate effects—they’re interconnected systems working together. Let me break down what’s actually happening.

Wish Fulfillment—The Hidden Engine

Here’s the mechanism that competitors describe without naming: wish fulfillment.

Dr. Jenny Radesky, Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Michigan Medical School and co-Medical Director of the American Academy of Pediatrics Center of Excellence on Social Media and Youth Mental Health, puts it directly: unboxing videos are “so engaging and mesmerizing to young kids because they have all of this wish fulfillment in them that kids just are very drawn to.”

This isn’t just “kids like toys.” It’s something more fundamental about how young brains process experiences.

Why Virtual Feels Real to Young Brains

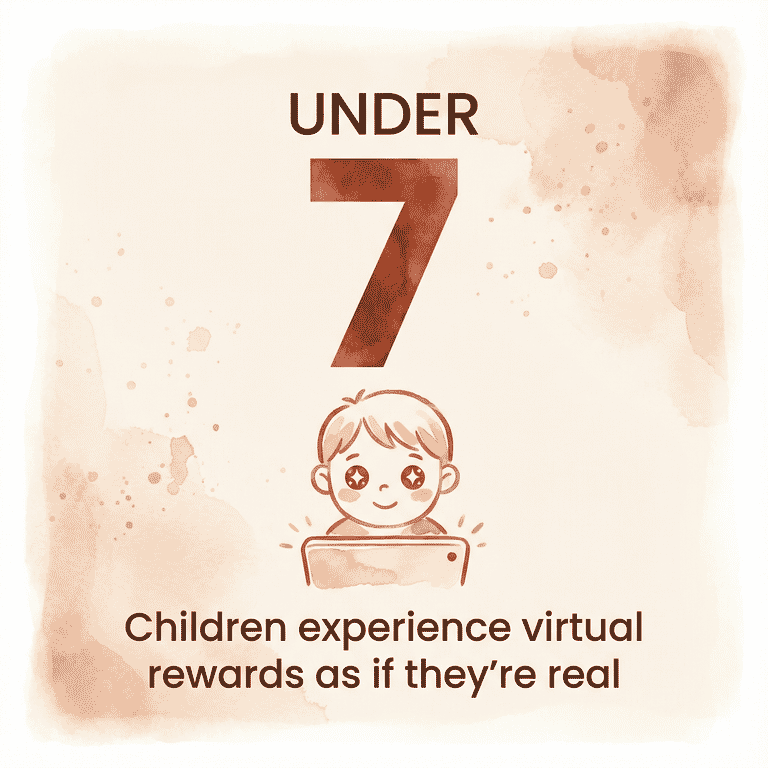

Children under 7 are still developing what psychologists call “theory of mind”—the ability to understand that others have different thoughts, motivations, and perspectives than they do. According to FTC research from 2023, many children under 7 haven’t developed this capacity fully, which affects how they experience all media—including unboxing videos.

When my 4-year-old watches someone open a surprise toy, she’s not thinking “that person is getting a toy.” On some level, her brain is experiencing a version of getting the toy herself.

The Reward Sensitivity Factor

Dr. Radesky describes observing her own two-year-old’s response to reward-based design: “He was like, ‘What? I got a present?!’… He was so obsessed with these games… ‘The treasure chest opened! Look at all these coins!’ And I was like, ‘Of course a two-year-old doesn’t know the difference between these fake gimmicky coins on a screen and like the real gold coins you might get in real life.'”

Young children are highly reward-sensitive. A 2024 analysis by MIT Press of over 1,600 videos viewed by children ages 0-8 found frequent branded, high-pleasure content (including unboxing) that engages young viewers through these exact reward-based mechanisms.

This is the core insight most articles miss: children aren’t just entertained by unboxing videos—they’re neurologically experiencing a form of the reward without ever touching a toy.

Understanding the science of how gifts affect the brain helps explain why the virtual experience feels so real to developing minds.

The Anticipation-Reward Loop

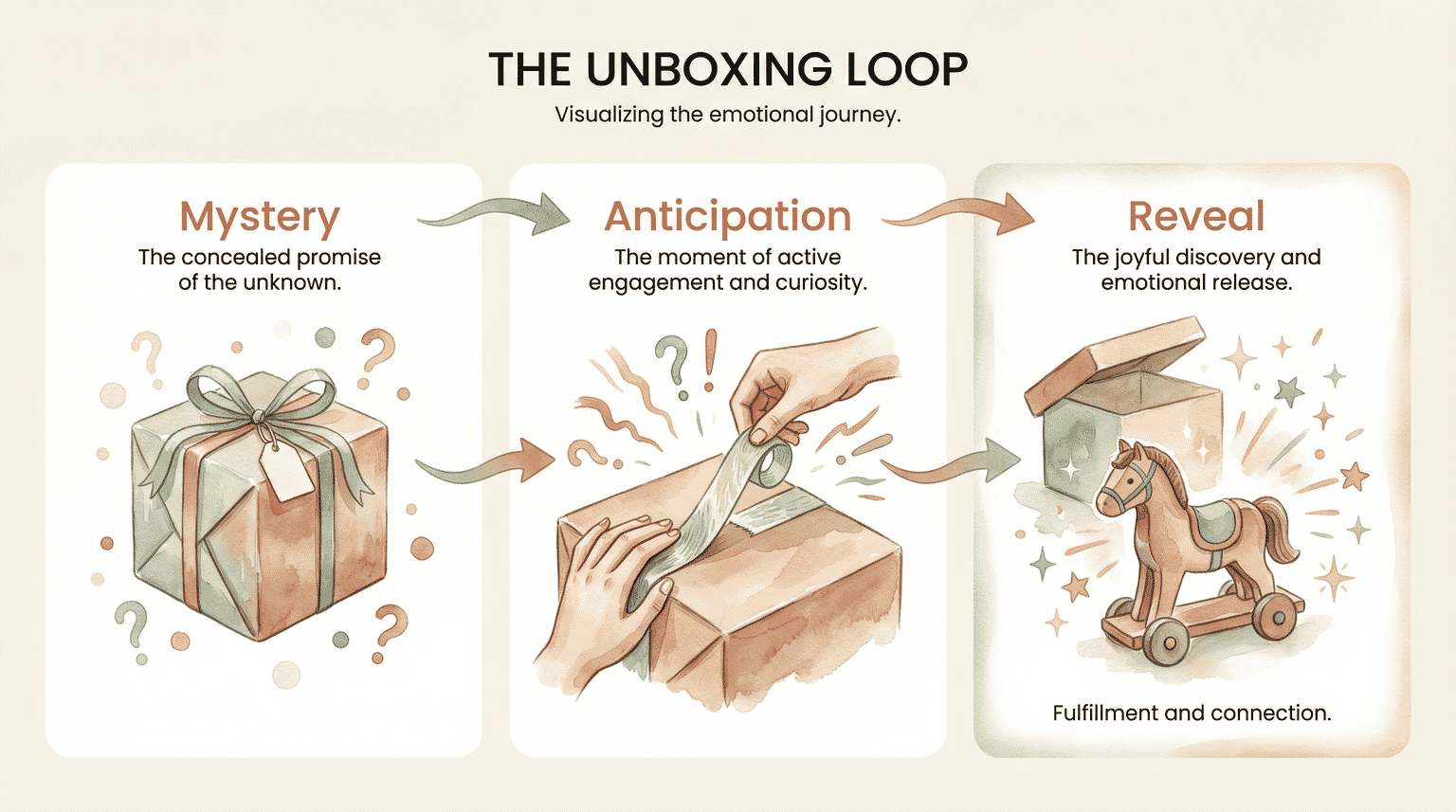

Every unboxing video follows the same three-act structure:

- Setup: Here’s a mysterious package

- Tension: Slow reveal, peeling, cutting, unwrapping

- Payoff: The toy appears

This structure isn’t accidental. It’s dopamine architecture.

The Three-Act Story Structure

When we anticipate something exciting, our brains release dopamine—not when we receive the reward, but when we expect it. Unboxing videos are essentially anticipation machines. The slow unwrapping, the cutaway shots, the “what could it be?” narration—all of it extends the anticipation phase, maximizing the dopamine release.

I’ve watched this with my own kids: they’re most engaged during the unwrapping, not after the reveal. The 8-year-old literally says “wait, don’t skip ahead!” when I try to fast-forward. The buildup is the experience.

Why Repetition Reinforces Rather Than Bores

You’d think the 47th unboxing would get boring. It doesn’t. The MIT Press research found that this repetitive structure actually strengthens the appeal—each video reinforces the reward pattern, making the next one more compelling, not less.

This is the same mechanism behind other repetitive childhood favorites (think: reading the same book nightly). But unlike books, the algorithmic delivery means there’s always another unboxing queued up.

Parasocial Bonds—Why Hosts Feel Like Friends

Here’s something that genuinely surprised me in the research: children form one-sided relationships with YouTubers that they experience as real friendships.

Sherri Hope Culver, Director of the Center for Media and Information Literacy at Temple University, explains the psychology: “I understand this character. I like him/her. This character likes me, too. We are friends. And I can engage with them whenever I want.”

This is called a parasocial relationship—a one-sided connection where the viewer feels genuine friendship with someone who doesn’t know they exist. (The term became so culturally significant that Cambridge Dictionary named “parasocial” its 2025 Word of the Year.) Adults experience this with celebrities too, but children experience it more intensely and with less cognitive distance.

One-Sided Relationships That Feel Mutual

When my 6-year-old talks about “Ryan” (of Ryan’s World), she talks about him like a classmate. She knows his favorite colors. She references inside jokes from his videos. She has feelings about his family members.

To her developing brain, the distinction between “real friend” and “person on screen” is genuinely blurry—not because she’s confused, but because her brain isn’t fully equipped yet to make that distinction automatically. For deeper exploration of how these parasocial relationships children form with online personalities affect their behavior, the research gets even more interesting.

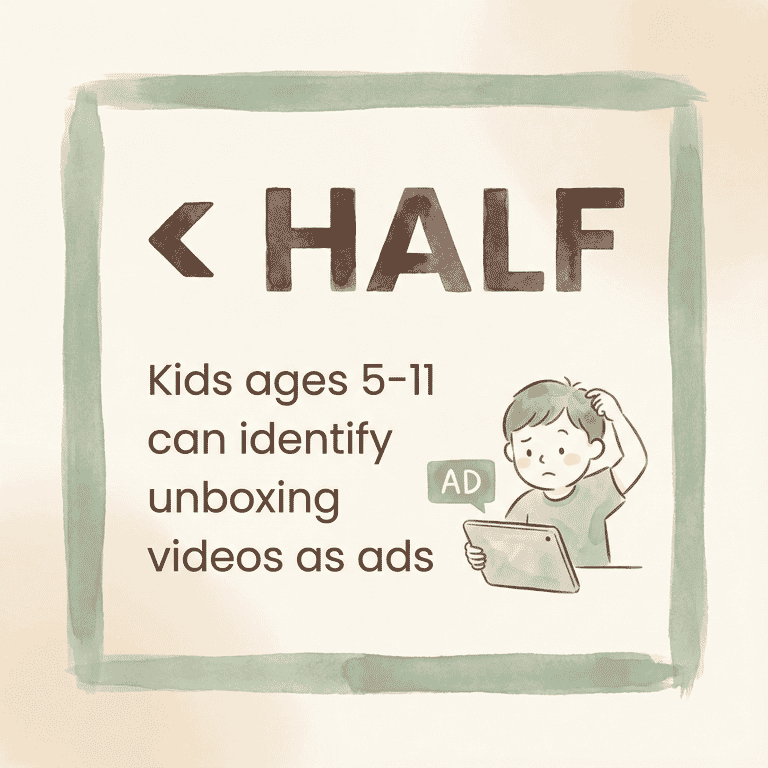

Why Disclosure Language Doesn’t Work

Here’s the frustrating part for parents and policymakers: even when videos include disclosures about paid promotions, it doesn’t change children’s behavior.

The American Academy of Pediatrics notes that experiments show only a small portion of preschoolers understand that ads aim to “sell you something.” The FTC found that fewer than half of children ages 5-11 could correctly identify an influencer ad or unboxing video as advertising—even when asked directly.

Disclosure requirements assume children have the cognitive capacity to process and apply that information. Most don’t until around age 12, when full advertising comprehension typically develops.

Understanding the hidden advertising in YouTube content children consume requires recognizing that the ads aren’t hidden from you—they’re hidden from your child’s developing brain.

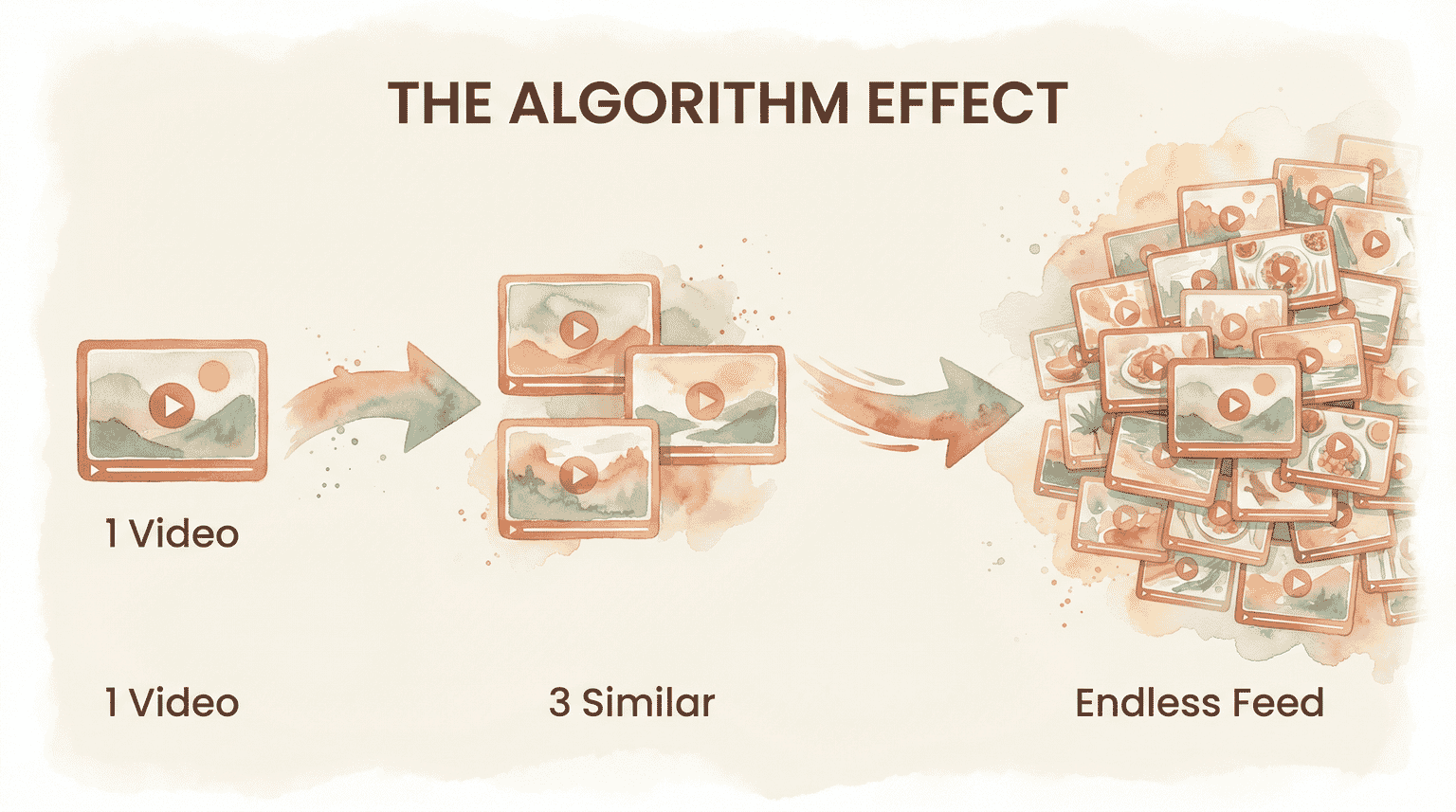

The Algorithm’s Amplifying Role

“It came out of nowhere” is what parents usually say. One day their kid was watching Sesame Street clips; the next, it’s an endless stream of unboxing content.

It didn’t come out of nowhere. The algorithm brought it.

How One Video Becomes a Hundred

Culver explains the mechanism clearly: “Whenever someone accesses a streaming platform or app like YouTube, that app starts to focus on doing whatever it can to keep you watching.”

When a child watches one toy video, the algorithm identifies content characteristics and viewer demographics. If your child watches Frozen content, it starts recommending Frozen-related videos—including videos of people playing with dolls from the movie.

One curious click becomes a self-reinforcing cycle. The algorithm learns your child’s engagement patterns and optimizes for maximum watch time, not developmental appropriateness. (Even YouTube Kids has the same fundamental problem.)

This is why parents feel ambushed. Your child didn’t seek out unboxing videos—the recommendation system sought out your child.

Sensory Satisfaction and ASMR Elements

This one gets less research attention, but parents notice it immediately: the sounds.

The crinkling of packaging. The snipping of scissors. The soft narration. The satisfying click of pieces fitting together. Many unboxing videos incorporate ASMR elements—sounds and visuals that trigger a relaxation response.

I noticed my 4-year-old literally leaning closer to the screen during unwrapping sounds. She wasn’t just watching—she was experiencing something almost physical.

These sensory elements operate below conscious awareness, creating a pleasurable viewing experience that children can’t fully articulate but definitely feel. It’s not the main driver of appeal, but it’s part of why these videos feel good in a way other content doesn’t.

Mimetic Desire and Identity Exploration

Here’s the angle almost no one talks about: unboxing videos help children figure out who they are.

Wanting What Others Want

Social learning theory (foundational work by Bandura) explains that children learn through observation—including what to want. When children watch someone express excitement about a toy, they learn that this toy is desirable. They want it because they’ve watched someone else want it.

This mimetic desire—wanting what others want—is a normal part of development. It’s how children learn cultural preferences, develop taste, and figure out what’s socially valued.

The Identity Formation Connection

Culver connects this to developmental stages: “At each stage of development, kids are trying to figure out who they are. They are exploring their own identity. At 2 or 3 years old, a child is starting to ask themselves, ‘What do I like? What is my thing?'”

Unboxing videos let children try on preferences virtually. Maybe I’m a Paw Patrol kid. Maybe I’m into dinosaurs. Maybe I’m a slime person. Watching others unbox helps children explore identity without the social risk of declaring a preference publicly.

This is why your child might watch hours of Monster Truck unboxing despite never asking for a Monster Truck. They’re not shopping—they’re identity testing.

Understanding why children seem to want everything they see requires recognizing that the “wanting” serves multiple developmental purposes, not all of which lead to actual desire for the object.

What This Means for Parents

So your child’s brain is being optimized for engagement by multi-billion-dollar platforms using psychological mechanisms they can’t consciously recognize or resist. Great.

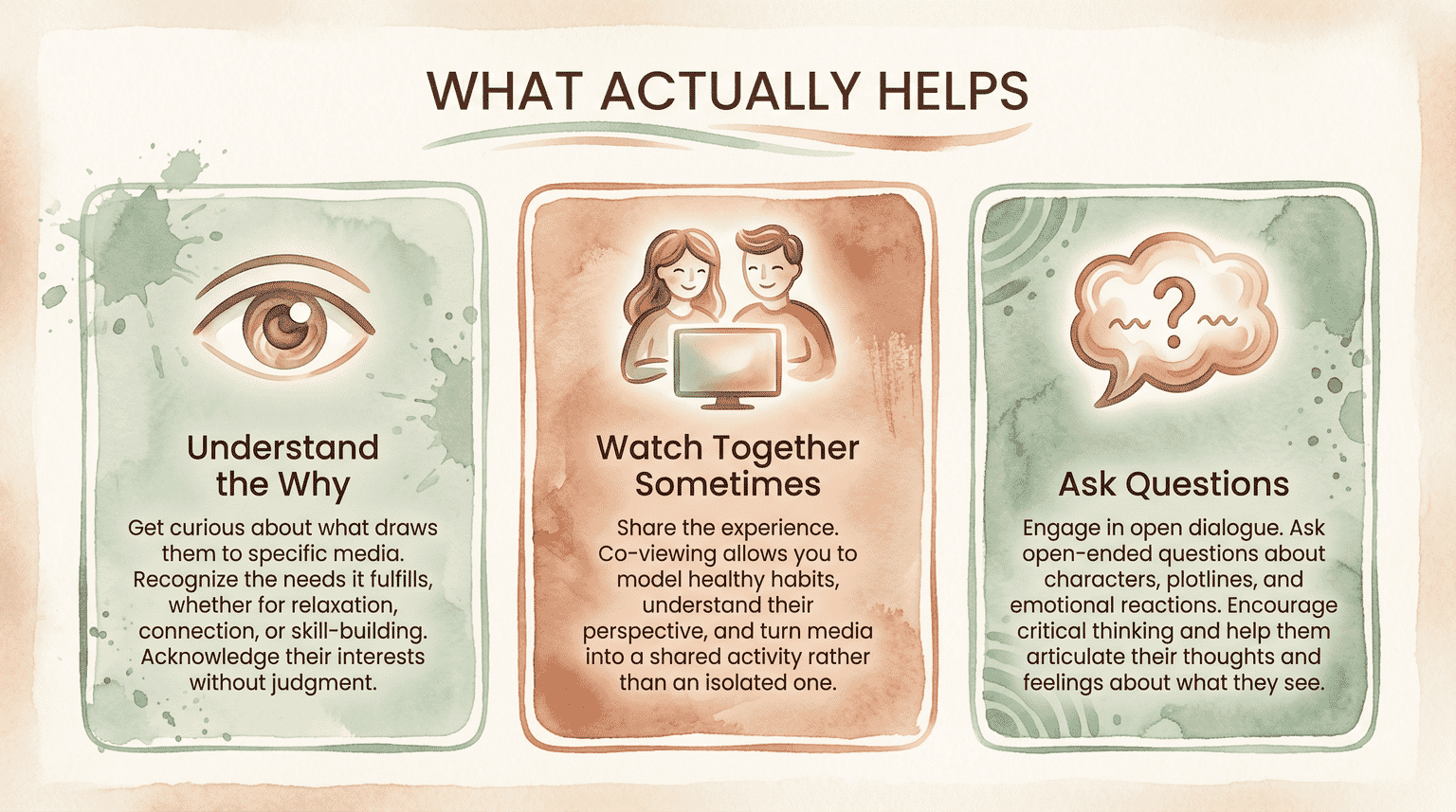

Here’s what I’ve found actually helps:

Understanding replaces panic. Once I understood the psychology, I stopped seeing unboxing fascination as a character flaw in my kids. Their brains are doing exactly what developing brains do—responding to well-designed stimuli.

Co-viewing beats restriction. Research from the OECD confirms that children learn more from media when adults engage in conversations around the content. Occasionally watching together and asking questions—”Do you think she got paid to show that?”—builds media literacy over time.

Active mediation grows with your child. BYU research suggests that younger children may benefit from restricted media time, while older children benefit from time limits combined with dialogue. As Dr. Jason Freeman explains: “When parents critically engage with this content created for children, they are able to teach their children how the content might shape their child’s attitudes and behavior.”

Connect it to your family’s broader media approach. Unboxing videos are one piece of how screens have changed the way children experience gifts—understanding that bigger picture helps you make intentional choices rather than fighting endless small battles.

I won’t pretend we’ve solved this in my house. My 6-year-old still loves unboxing videos. But understanding why has changed how I respond—with curiosity instead of frustration, with conversations instead of just limits. For practical ideas, see 5 unboxing alternatives kids actually love.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are unboxing videos bad for kids?

Unboxing videos aren’t inherently harmful, but they present specific concerns for young children. According to the FTC, fewer than half of children ages 5-11 can recognize these videos as advertising—meaning they absorb commercial messages without the filters adults automatically apply. The greater concern isn’t individual videos but cumulative effects: increased product requests, difficulty distinguishing entertainment from advertising, and parasocial relationships that make children unusually receptive to commercial influence.

Why are unboxing videos so addictive?

Unboxing videos trigger multiple reward systems simultaneously. The anticipation-and-reveal structure activates dopamine pathways—children’s brains experience a “reward hit” similar to opening a present themselves. Dr. Jenny Radesky describes this as “wish fulfillment”—young children can’t fully distinguish between watching something exciting happen and experiencing it personally, making these videos neurologically compelling in ways adult brains don’t register the same way.

At what age can kids understand unboxing videos are ads?

Children’s ability to recognize advertising develops gradually. According to FTC research, children under 7 typically haven’t developed the “theory of mind” needed to understand persuasive intent. Around ages 7-8, children begin identifying that someone might be trying to sell them something. Full advertising comprehension—understanding the commercial relationship between creators and brands—typically develops around age 12.

How do I stop my child from watching unboxing videos?

Rather than outright bans, child development experts recommend “active mediation”—watching together occasionally and asking questions like “Do you think they get paid to show these toys?” or “How do you feel after watching?” Dr. Jason Freeman notes that when parents critically engage with content, they help children recognize how it might shape their attitudes and behavior. Complete restriction is less effective long-term than building media literacy.

What About You?

How do you handle unboxing videos at your house—ban, limit, or watch together? I’m curious what’s worked for managing the “I want that” aftermath without constant battles.

Your unboxing strategies help other parents navigate this tricky balance too.

References

- Federal Trade Commission Staff Perspective (2023) – Children’s advertising recognition and digital media exposure

- MIT Press: Digital Wellbeing in Early Childhood (2024) – Analysis of children’s video content and reward-based engagement

- Children and Screens: Dr. Jenny Radesky Interview (2025) – Wish fulfillment and reward sensitivity in young children

- Brigham Young University News (2022) – Parental awareness of commercial content and “pester power”

- Temple University: Center for Media and Information Literacy (2025) – Algorithm effects and identity formation

- American Academy of Pediatrics Q&A Portal (2023) – YouTube marketing to children

- OECD: Impact of Digital Activities on Children’s Lives (2025) – Digital wellbeing and joint media engagement

Share Your Thoughts