Your child is watching a YouTube video. A smiling 8-year-old opens a surprise egg, gasps at what’s inside, and your kid immediately wants one. “It’s not a commercial,” they insist when you suggest turning it off. “She’s just playing.”

Here’s the thing: your child is technically right—it doesn’t look like a commercial. And that’s exactly the point.

My librarian brain couldn’t let this go. After watching my 6-year-old narrate her own “unboxing” of a cereal box (complete with dramatic pauses and “wow, look at that!”), I dove into the research. What I found is a marketing system specifically designed to slip past children’s natural skepticism—because developmentally, they don’t have the tools to recognize it yet.

Key Takeaways

- Children under age 8 cannot distinguish advertising from entertainment—their brains haven’t developed that capacity yet

- Toy companies use 7 specific tactics to make marketing feel like organic content

- Kids develop “parasocial relationships” with YouTube personalities, trusting recommendations like advice from a real friend

- The surprise element in blind bags activates the same psychology that makes gambling compelling

- Recognition is the first step—you can build your child’s advertising literacy gradually

The Scale of What We’re Dealing With

The numbers stopped me cold. According to Pew Research Center’s 2025 data, 62% of children under age 2 now watch YouTube—up from 45% in 2020—with 35% watching daily. By 2018, just two toy unboxing channels—Ryan ToysReview and FunToys Collector—had amassed 38.6 billion views combined. Those numbers have only grown since.

That’s not a typo. Billion, with a B.

Michael Rich, director of the Center on Media and Child Health at Boston Children’s Hospital, puts it bluntly: unboxing videos teach children “to want things” and feed into “give me” culture.

The unboxing genre has grown 871% since 2010. What started with tech enthusiasts opening iPhones has become a sophisticated marketing channel targeting children who can’t yet distinguish entertainment from advertising.

Why It Doesn’t Feel Like an Ad

Here’s what the research actually shows about why children—even smart, media-savvy children—can’t recognize these videos as marketing.

A Universidad Villanueva study found that children aged 10-12 often failed to recognize product-centric YouTube videos as advertisements “due to their limited definition of advertising.” They’re looking for what they know ads look like: storylines with music, groups of actors, exaggerated claims, explicit price information.

“It’s not an advertisement. An ad should have a story and music… content should be more exaggerated.”

— 12-year-old study participant, Universidad Villanueva research

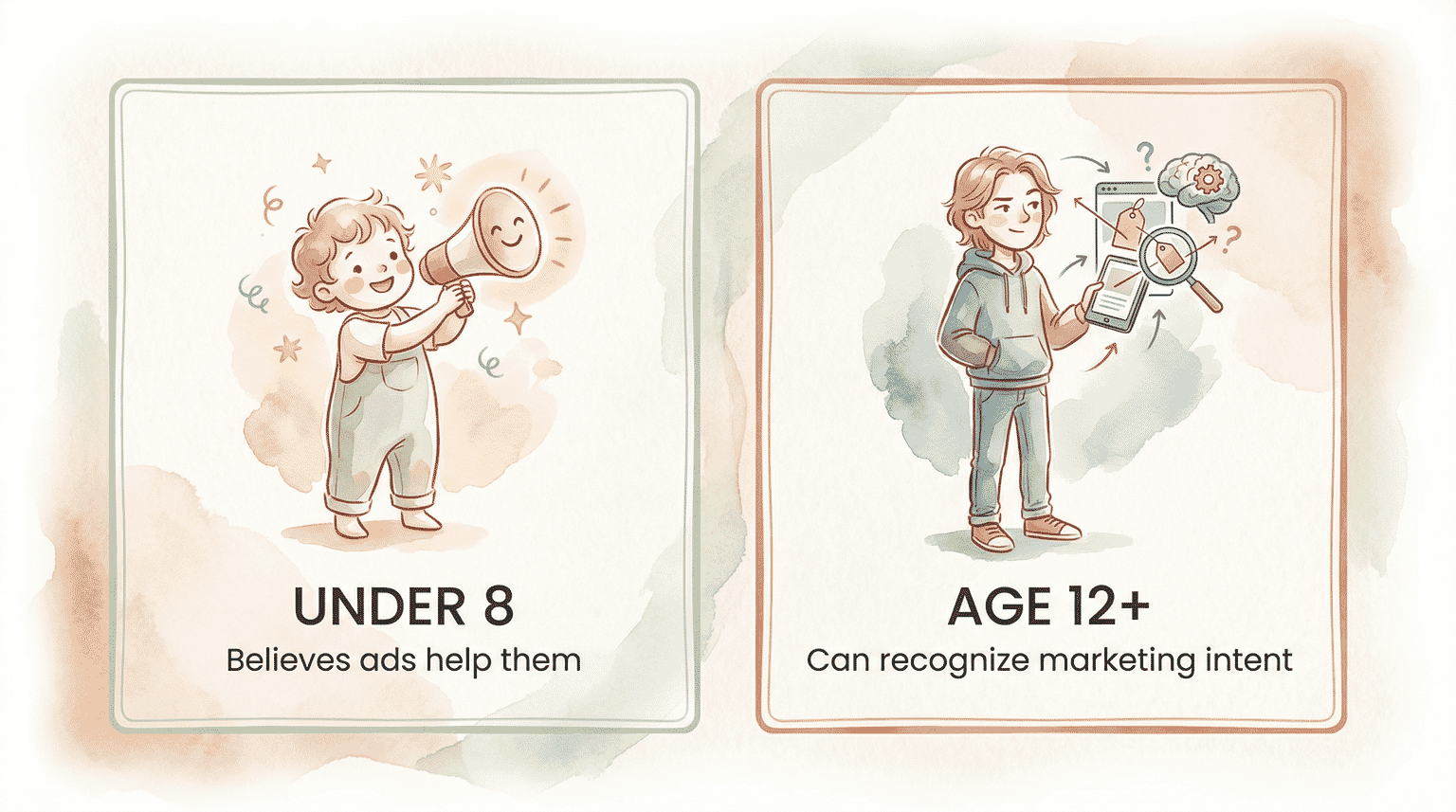

The developmental timeline is sobering. Research from the University of Mary Washington confirms that children under age 8 believe commercials are designed to help their purchasing decisions—they’re completely unaware of persuasive intent. Full comprehension doesn’t develop until around age 12.

This means most elementary-age children watching toy content literally cannot identify it as marketing. It’s not that they’re being foolish—their brains haven’t developed that capacity yet.

The Production Playbook: 7 Tactics Decoded

So what exactly are toy companies doing? I’ve broken down the specific strategies researchers have identified—tactics you can now spot in your child’s favorite videos.

1. Strategic Product Placement

Toys appear as prizes, family members wear branded merchandise, and branded content fills backgrounds. Nothing screams “advertisement”—it all feels incidental.

2. Sound Engineering

Upbeat music during unboxing. Clapping and cheering. Harp sounds when something sparkles. These audio cues create excitement that children absorb without processing critically. Some content incorporates ASMR elements—those satisfying crinkling and tapping sounds that create sensory pleasure.

3. Visual Effects

Zoom effects, rapid cuts, confetti graphics. Research notes that adults understand these are added in post-production, but children under 8 cannot easily recognize this manipulation.

4. Repetition Patterns

Full brand names stated multiple times. Multiple camera angles showing packaging and toys. Links in video descriptions. The repetition is strategic—children learn through repetition, and marketers know it.

5. Branded Character Ecosystems

Take Ryan’s World empire—what started as one channel became clothing lines, toy lines, a Nickelodeon show, smartphone apps, video games, and five related YouTube channels. By age eight, Ryan had become what researchers call “a global brand.”

6. Appeals Framework

Content analysis reveals consistent appeals: fun/happiness through positive reactions, functionality highlighting toy features, size/quantity emphasis, rarity promotion for collectibles, and variety showcasing color options.

7. The “Natural” Strategy

“Commercials don’t work on YouTube. If you want us to make a commercial for you, you are shooting yourself in the foot. If you want us to make a video using your stuff naturally, we may be able to get you millions of views.”

— Industry insider, Gabe and Garrett YouTube channel

Let that sink in. The strategy is explicitly designed to not look like what it is.

The Surprise Element Trap

My 4-year-old is currently obsessed with blind bags—L.O.L. Surprise being the most successful example of toys designed specifically for this medium. I needed to understand why.

Caroline Jack, Associate Professor at UC San Diego, explains the psychology: “Blind box releases, in which the purchaser doesn’t know which variant they’ve purchased until they open the box, create additional excitement around a purchase because they introduce an element of chance. This makes unboxing into an important part of the consumer experience.”

That element of chance? It’s the same psychology that makes gambling compelling. And toy companies have engineered their packaging specifically to maximize this effect—what researchers call “unboxing-optimized packaging.” The crinkle of the wrapper, the reveal moment, the anticipation—none of it is accidental.

Collectibles amplify this further. The appeals framework researchers identified includes “rarity promotion”—messaging that certain items are harder to find, creating urgency and repeated purchases.

The Algorithm Machine

One toy video becomes ten. Ten becomes an afternoon. Here’s why.

A Pew Research study analyzed by UNLV researchers found that YouTube’s recommendation algorithm consistently recommended children’s content regardless of what video category users started in. Of 346,086 unique videos analyzed, the single most recommended video was animated children’s content.

The algorithm doesn’t care about your child’s bedtime or your family’s values around screen time. It’s optimized for engagement—and toy content, with its bright colors, excited voices, and constant novelty, is engineered to deliver exactly that.

This matters for understanding how digital culture shapes children’s expectations. One video isn’t the problem. The endless, autoplay-fueled loop is.

The Parasocial Bond

Here’s where it gets psychologically sophisticated.

Children develop what researchers call “parasocial relationships” with YouTube personalities—one-sided emotional bonds where viewers feel like they genuinely know the person on screen. Professor Jack explains that social media allows influencers to cultivate “appearances of direct, authentic connection,” making viewers feel “almost as if we know” these media figures.

For children, these bonds are especially powerful. Research on smart toys and children’s psychology confirms that children are “especially susceptible to overtrust risks because children cannot adequately assess hazards of sophisticated technological devices.”

This explains why your child trusts a kid YouTuber’s toy recommendations like advice from a friend—developmentally, that’s exactly how it feels to them.

The advocacy group Truth in Advertising filed a complaint noting that “organic content, sponsored content—it’s all the same to preschoolers. Ryan ToysReview’s sponsored content is presented in a manner that misleadingly blurs the distinction between advertising and organic content for its intended audience.”

Even when content includes FTC-required disclosures, research shows children with strong parasocial relationships maintain positive brand attitudes regardless. The emotional connection overrides any critical response.

What This Means for Parents

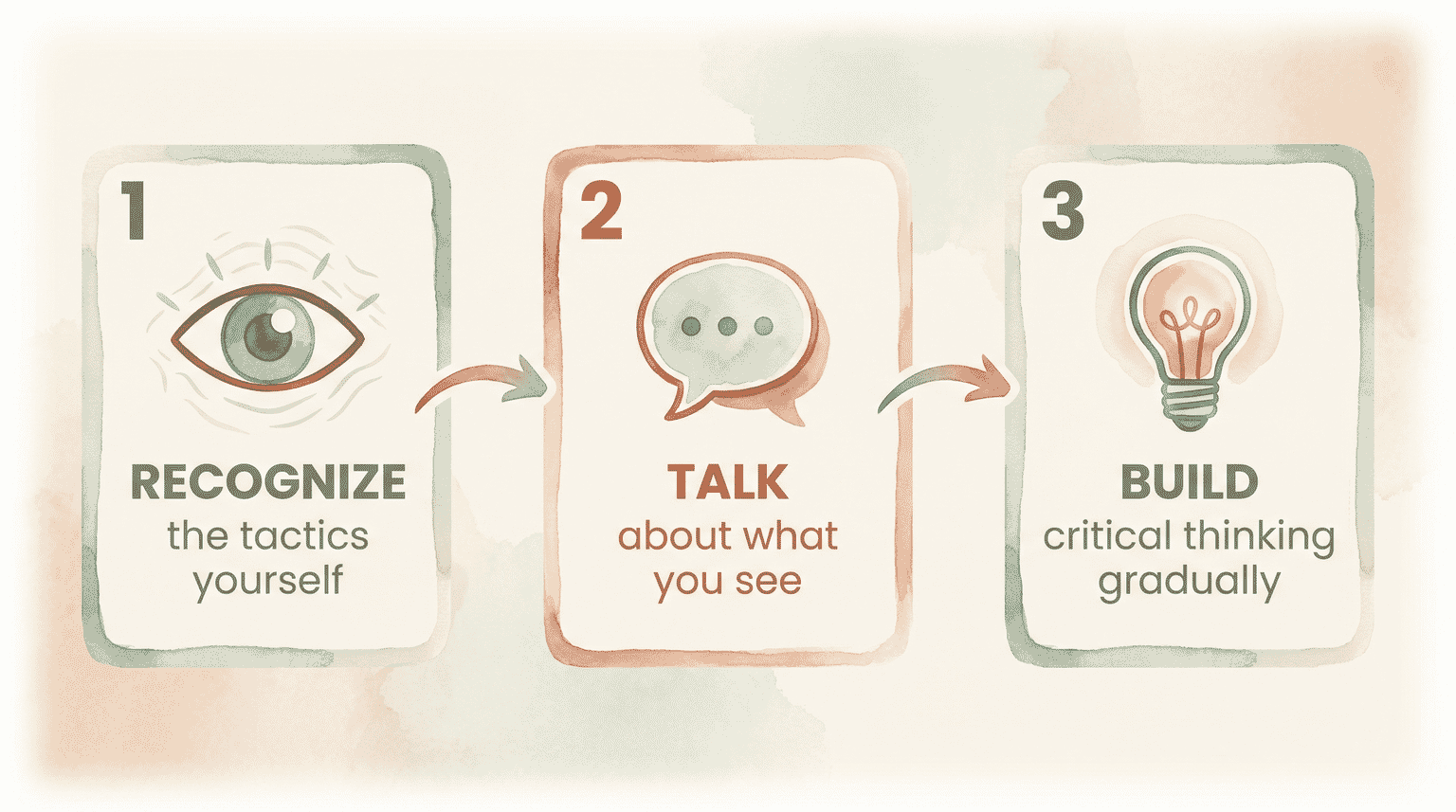

I’ve watched this play out eight times now, across every age from toddlers to teens. The research confirms what I’ve observed: recognition is the first step.

You can’t protect children from tactics they don’t understand—but you can understand them. When you recognize the harp sounds, the repetition, the “natural” product placement, you’re equipped to have real conversations with your kids about what they’re watching.

This isn’t about banning YouTube or making your kids feel foolish for wanting things. It’s about building their advertising literacy gradually, appropriate to their developmental stage.

For practical strategies for reducing unboxing video dependence, the key isn’t fighting the content—it’s helping children develop the critical thinking skills that their brains are still building.

Frequently Asked Questions

At what age can children recognize YouTube ads?

Children under age 8 cannot distinguish advertising from entertainment content. Recognition develops gradually, with most children beginning to identify some embedded marketing around age 11-12. Research found the average age for recognizing all hybrid advertising formats was 12.66 years.

Are unboxing videos considered advertising?

Legally, sponsored unboxing videos are advertising requiring FTC disclosure. However, children don’t perceive them this way. In one study, 20 of 30 children ages 10-12 did not consider product endorsement videos to be advertisements, defining “ads” by traditional TV commercial characteristics.

Why does my child want every toy they see on YouTube?

Two mechanisms drive this: parasocial relationships and surprise psychology. Children develop emotional bonds with YouTube personalities, trusting recommendations like friend advice. Additionally, blind bag and unboxing content activates chance-based excitement—the same psychology that makes gambling compelling.

How do toy companies use influencers?

Rather than traditional commercials, toy companies partner with family channels to embed products into entertainment. Toys appear as prizes, background props, and natural play elements—an approach that bypasses children’s advertising defenses because content doesn’t match their mental definition of “an ad.”

Share Your Story

Have you noticed the toy industry’s YouTube strategy at work in your house? I’d love to hear which toys came from “nowhere” (aka carefully placed videos) and whether your kids realized they’d been marketed to.

Your stories help other parents decode what’s really happening on their screens.

References

- Universidad Villanueva (2023) – Research on children’s recognition of hybrid advertising formats

- Pew Research Center (2025) – Updated statistics on children’s YouTube viewing habits

- Journal of Childhood Studies – Analysis of YouTube consumption and unboxing phenomenon scale

- University of Mary Washington (2025) – Content analysis of Ryan’s World advertising strategies

- UNLV – Research on YouTube algorithm behavior and kidfluencer regulation

- UC San Diego – Expert analysis on blind box psychology and parasocial relationships

- NIH/PMC – Research on children’s vulnerability to sophisticated technological marketing

Share Your Thoughts