The toys keep arriving. Birthday parties, holidays, “just because” gifts from grandparents—your playroom is overflowing, and you know some of these toys should find new homes. But how do you teach your child to let go without tears, guilt, or resentment?

Here’s what the research actually shows: when parents talk about giving to charity, their children are 20% more likely to give themselves. Even more striking, 80.5% of children whose parents donated continue giving as adults. The habits you build now genuinely matter long-term.

I’ve navigated this with eight kids across every developmental stage—from my 2-year-old who thinks donating means “bye-bye toy forever” to my teenagers who now independently choose causes they care about. Here are the five strategies that actually work.

Key Takeaways

- Let kids choose which toys to donate—forced giving backfires and creates lasting negative associations

- Frame inequality as circumstance, not effort—children are 75% more likely to share when they understand unfairness isn’t someone’s fault

- In-person donation creates lasting impact; abstract giving doesn’t stick

- Build regular rhythms (one-in-one-out, seasonal check-ins) so generosity becomes normal, not exceptional

- Address the upstream problem—one conversation with grandparents prevents three decluttering sessions

Start with the Source: The Grandparent Conversation

Before you tackle the overflowing toy bins, consider addressing the upstream problem. In my experience, one honest conversation with grandparents before a birthday can prevent three stressful decluttering sessions afterward.

This isn’t about rejecting their generosity—it’s about redirecting it. Research from the University of Texas confirms that social networks significantly shape giving behavior. When your extended family models intentional generosity rather than quantity-focused giving, children absorb that value too.

Timing matters. Have these conversations 2-3 weeks before gift-giving occasions—not the day before, when everyone feels pressured. Frame it around wanting gifts to be memorable and meaningful rather than lost in a pile.

Try saying: “The kids treasure the special toys you pick out. Would you consider one meaningful gift this year, or maybe an experience we could do together? We’re trying to help them appreciate what they have.”

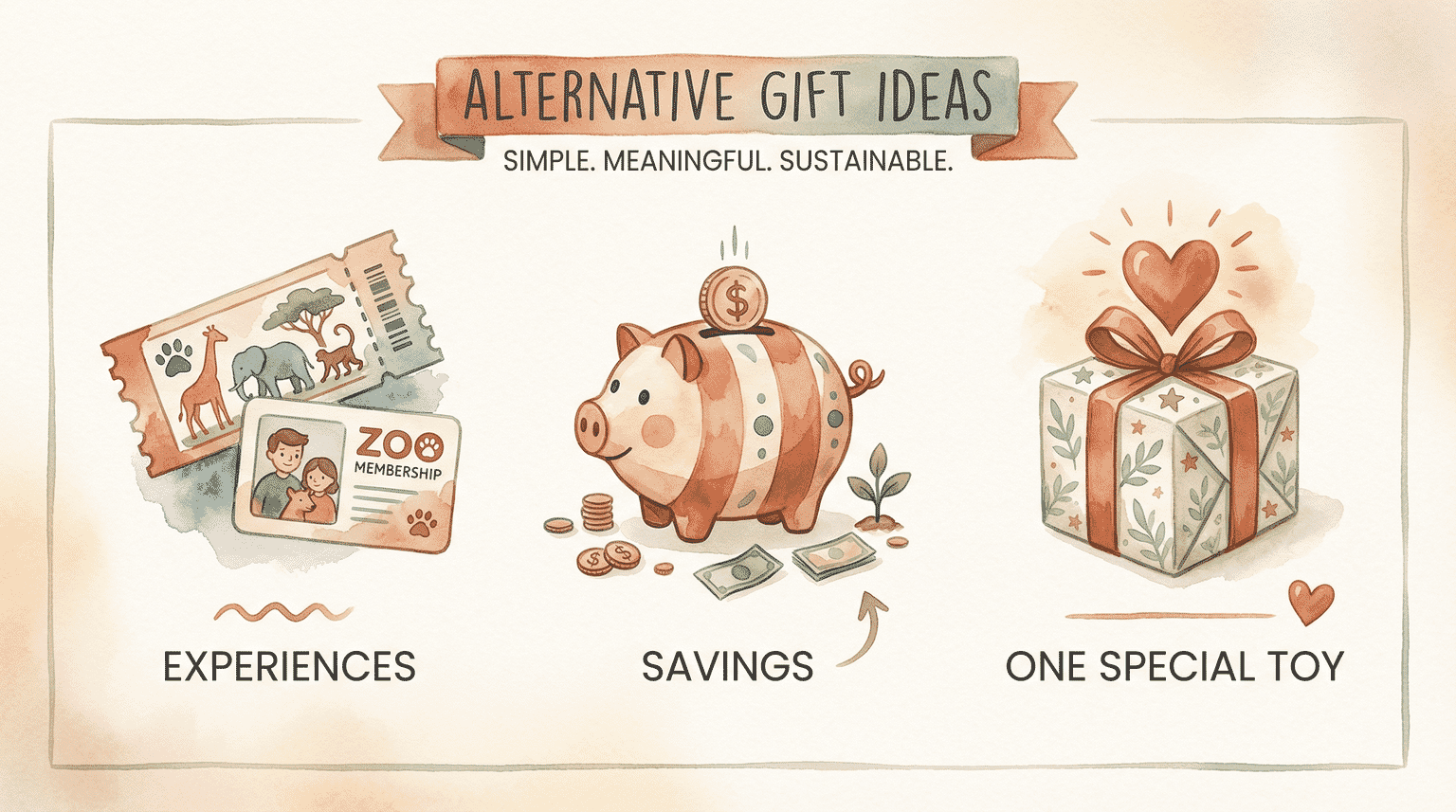

Offer concrete alternatives: experience gifts (zoo memberships, movie dates), contributions to education savings, or one special toy rather than several. If you’re navigating broader gift overflow from extended family, having these conversations becomes even more essential.

Make Giving Their Idea: The Child-Led Choice Strategy

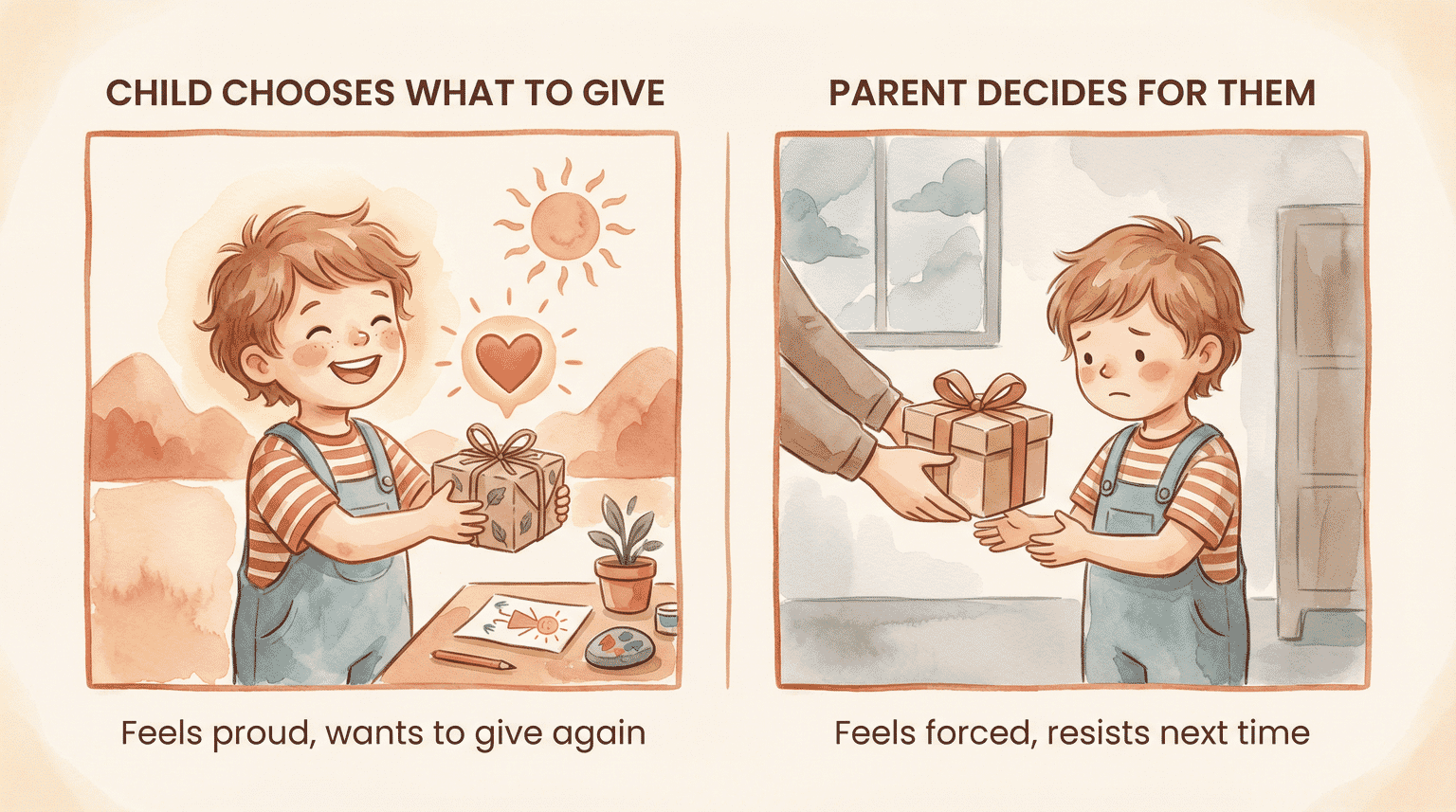

Here’s where most parents go wrong: we decide which toys should go, then try to convince our kids to agree. The research suggests flipping this entirely.

Harvard researchers found that three conditions maximize happiness from giving: having choice about what and where to give, being actively engaged in the process, and seeing the results. When any of these elements is missing—especially choice—giving doesn’t feel good. And when giving doesn’t feel good, children don’t want to do it again.

“Get your children to be the driver of it and don’t dictate for them what it is they should be doing or what organization they can be giving to.”

— Stephanie Mackara, Wealth Advisor specializing in family generosity

Practical ways to offer choice without overwhelming:

- “Would you like to pick 3 toys to donate, or 5?”

- “Which stuffed animals have you finished loving?”

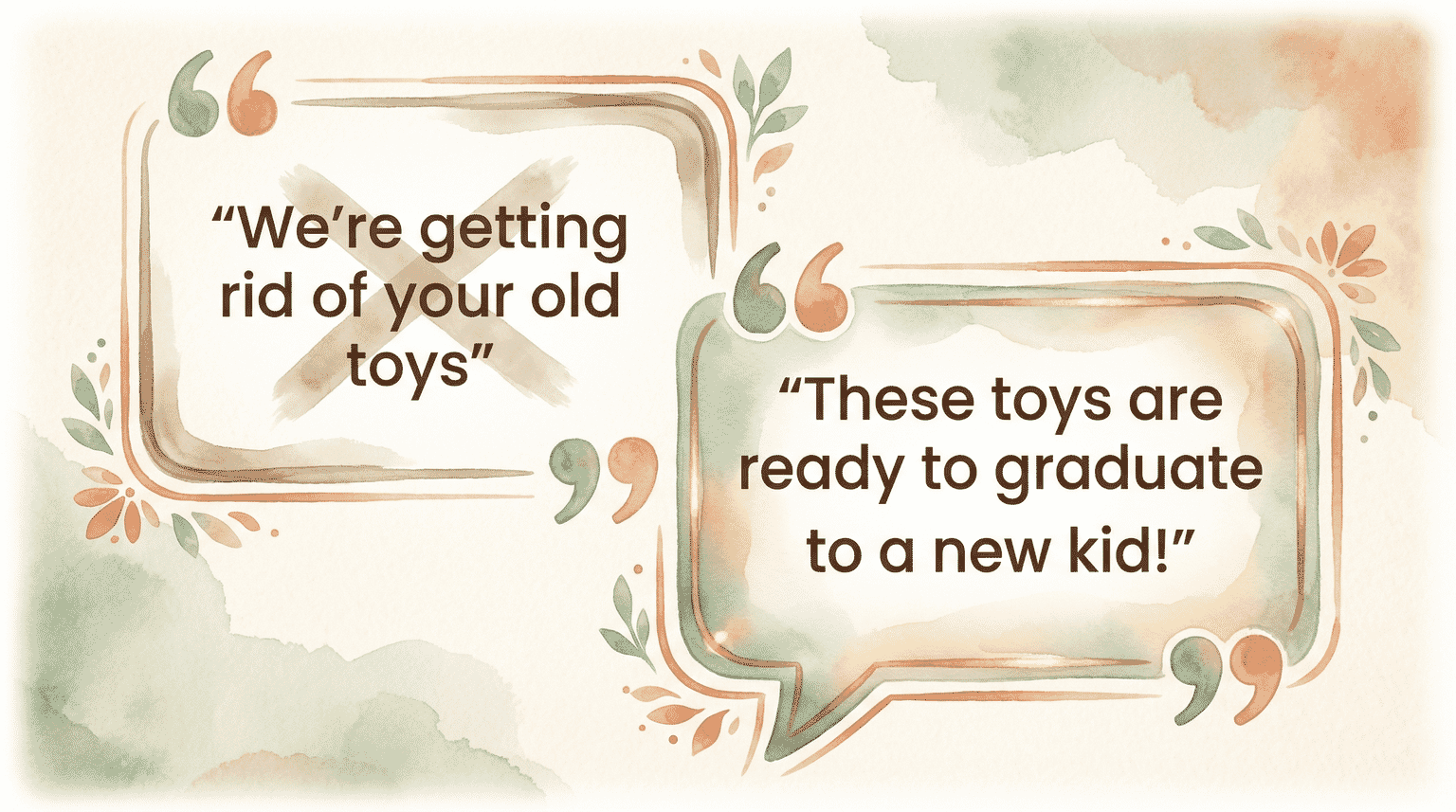

- “These toys are ready to graduate to a new kid—which ones should go first?”

That “graduation” reframe matters. In my house, saying a toy is ready to “graduate to a new home” works far better than implying it’s being taken away. My 6-year-old now proudly announces when a toy has “graduated”—he sees it as growth, not loss.

What to avoid: Donating toys secretly while your child is at school backfires spectacularly when they notice. Forced donation creates negative associations that persist. And guilt-based messaging (“You have too much”) rarely inspires genuine generosity.

The words we choose shape how children experience the entire process. When donation feels like loss, they resist. When it feels like growth, they participate.

Frame It Right: How to Explain Why Donation Matters

This is where research changed how I talk to my kids.

A Harvard study discovered something striking: when children understood that inequality was due to circumstances rather than effort, they shared resources 75% of the time. When they believed differences resulted from how hard people worked? Only about one-third shared.

The problem? Sixty percent of children naturally assume that people have less because they didn’t try hard enough. They’ve absorbed “work hard equals success” messaging everywhere.

How we explain inequality directly shapes whether kids want to help—or whether they think others simply deserve less.

Instead of: “Some kids don’t have any toys.”

Try: “Some families don’t have extra money for toys because of their situation—not because of anything they did wrong. The parents work really hard, but some things happened that made it tough for them.”

“The starting line is not the same for everyone, and they might have a head start as compared to others.”

— Ashley Whillans, Harvard Business School Professor

This isn’t about making kids feel guilty for what they have—it’s about building accurate understanding of why some children have less.

The character attribution technique: After your child donates, praise who they are, not just what they did. Dr. Mark Wilhelm, who studies charitable giving at Indiana University, explains that when we say “you’re a generous person” rather than just “that was nice,” children “start to internalize it and think of it as part of their identity and their character.”

I’ve watched this play out with my own kids. My 10-year-old now describes herself as “someone who shares”—it’s become part of how she sees herself.

When generosity becomes identity rather than obligation, children seek out opportunities to give rather than avoiding them.

Make It Real: Why In-Person Donation Works

Abstract giving—putting toys in a bag that disappears—doesn’t create lasting impact. Tangible experiences do.

“It might be even better to get the children actively involved in the giving… by donating their toys in-person or donating clothes to programs that help other children in need as opposed to simply helping their parents write a check.”

— Ashley Whillans, Harvard Business School Professor

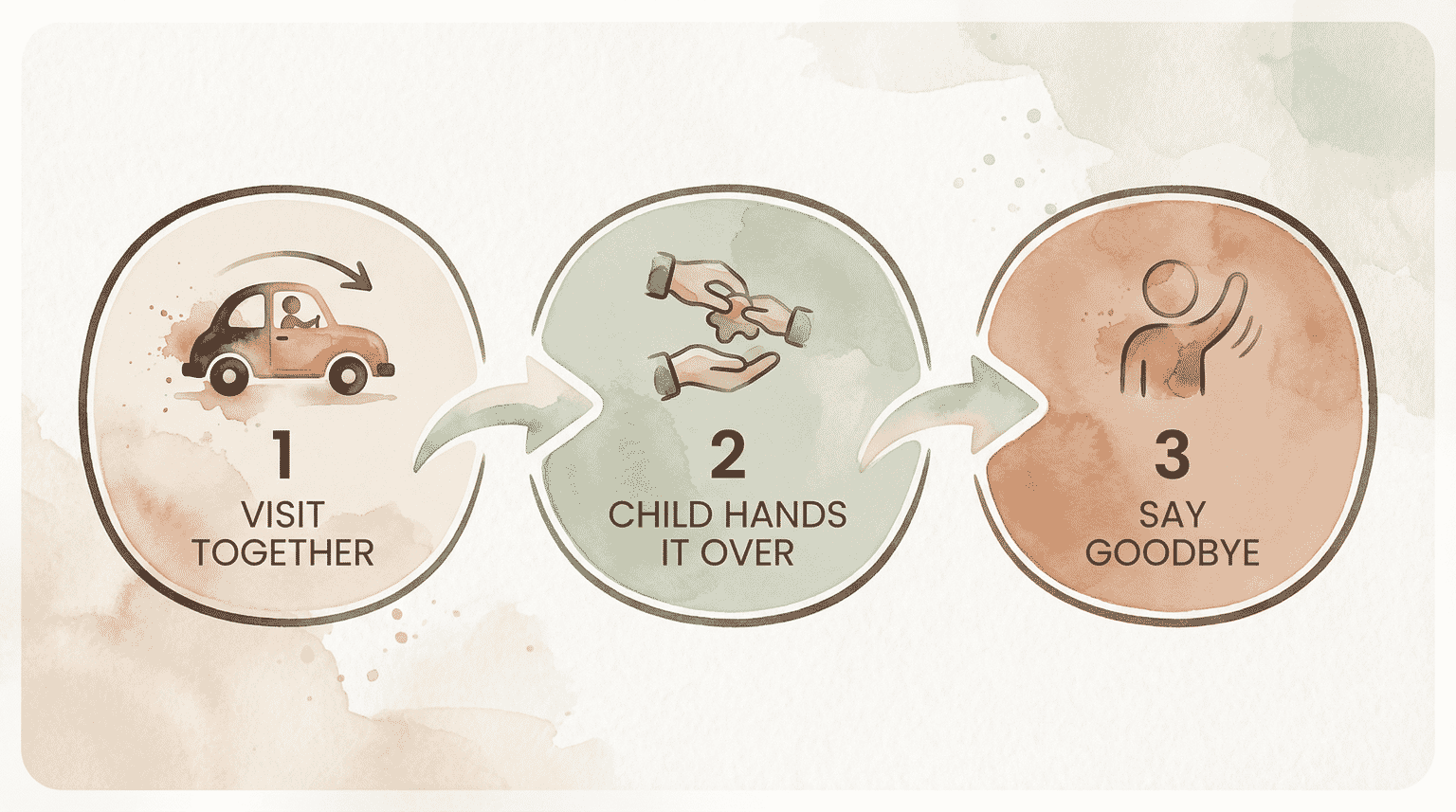

The Harvard research on giving happiness identified seeing results as one of the three essential conditions for prosocial joy. When your child watches someone accept their donation—when they see the toy go onto a shelf where another child will find it—giving becomes real.

Ways to make donation tangible:

- Visit the donation center together (treat it like a field trip)

- Let your child hand the bag to the worker

- Choose local organizations where impact is visible

- If possible, find programs that share stories or photos of recipients

Before we leave for donation drop-offs, we do a quick “thank you ritual”—each child says goodbye to their toy and wishes it well with its new owner. It sounds a bit silly, but it honors the attachment while creating closure. My 4-year-old waves goodbye to every single item.

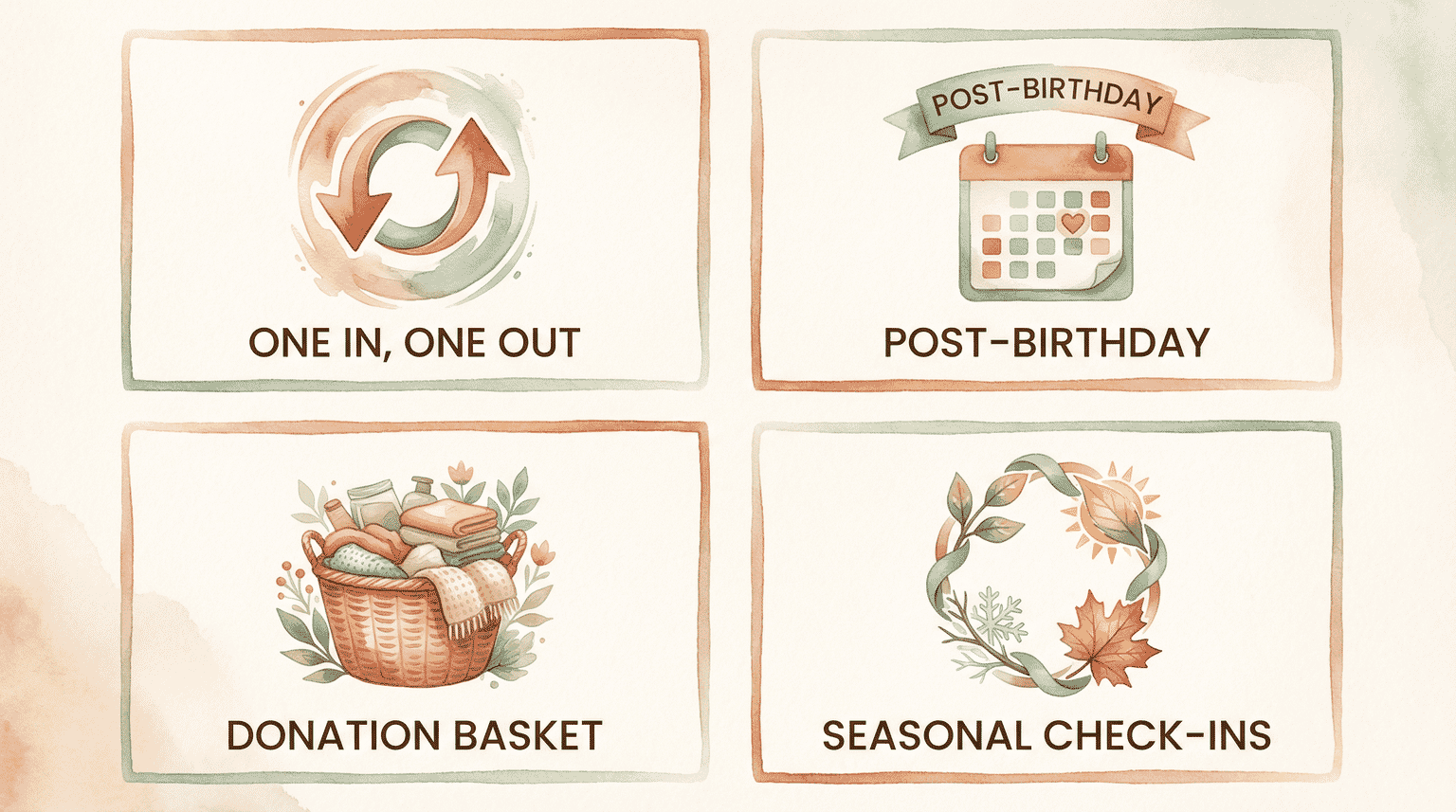

Build the Rhythm: Sustainable Systems That Stick

One-time cleanouts don’t create givers. Regular practice does.

“You have to let them know that you are doing it yourself and the child has to see that it is a regular part of the parent’s flow of life.”

— Dr. Mark Wilhelm, Indiana University charitable giving researcher

Children need to see generosity as normal, not exceptional. Research suggests children typically lose interest in toys within about 12 weeks. This creates natural donation windows—roughly 2-3 months after birthdays or holidays, when the shine has worn off and kids can more easily identify what they’re done with.

Systems that work in my house:

- One-in-one-out rule: New toy arrives, one toy graduates

- Post-birthday timing: Donation conversation 6-8 weeks after gift-receiving occasions

- Donation station: A designated basket where outgrown toys wait for drop-off

- Quarterly rhythm: Seasonal check-ins (“Summer’s coming—let’s see what’s ready to move on”)

The researchers call it the “positive cascade” effect: positive emotions from giving reinforce the behavior, making children more likely to seek out similar opportunities. Each good donation experience makes the next one easier.

Consider pairing donation rhythms with a toy rotation system. When toys regularly cycle in and out of play, children become more comfortable with the idea that not everything needs to be accessible—or kept—forever.

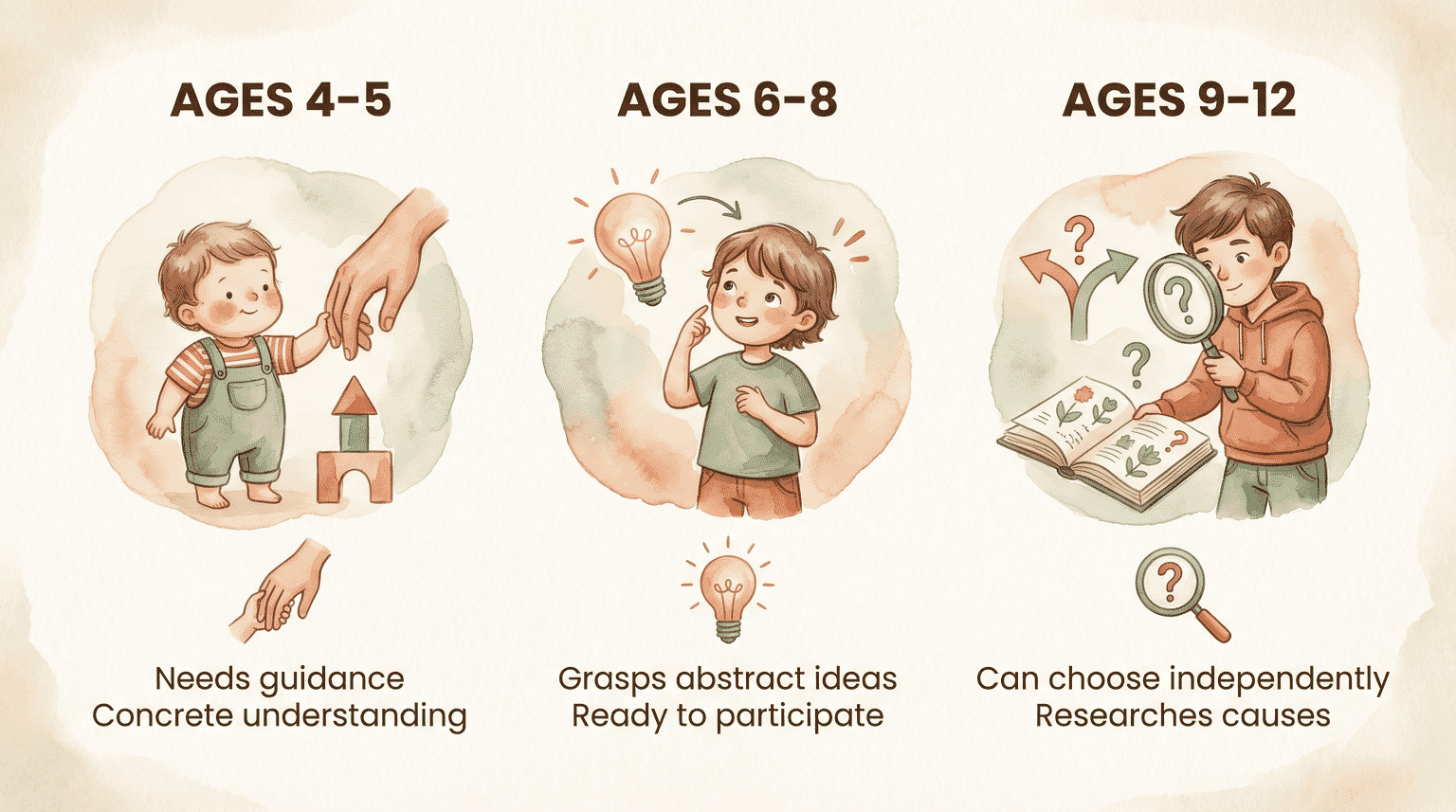

Age Readiness: What to Expect

A 2021 NIH study on children’s prosocial behavior found significant developmental differences in how children approach donation:

- Ages 4-5: Can participate in sorting with heavy guidance. Understanding is concrete—they need to see where toys go.

- Ages 6-8: Notable increase in donation behavior. Can grasp abstract concepts like “some kids don’t have toys.”

- Ages 9-12: Ready for autonomous decision-making. Can research organizations and choose recipients independently.

If your 4-year-old struggles more than your 7-year-old, that’s developmentally normal—not a character flaw.

Frequently Asked Questions

At what age can kids understand donating?

Children as young as 4 can participate in donation decisions with guidance, though understanding deepens significantly around ages 6-8. Research shows 6-year-olds display notably more donating behavior than 4-year-olds, with another increase at age 8 as abstract thinking develops.

Should you force kids to donate toys?

No—forced donation creates negative associations that can persist into adulthood. Research shows children experience more satisfaction from giving when they have choice. However, parents can set expectations that donation is part of family life while offering structured choices about which toys and when.

How do I talk to my child about why some kids don’t have toys?

Focus on circumstances rather than effort. Research found children are 75% more likely to share when they understand that others’ situations aren’t their fault. Say: “Some families don’t have extra money for toys because of their situation, not because of anything they did wrong.”

Your Turn

How do you handle toy donations in your house? I’ve tried the “one in, one out” rule and the pre-birthday purge—with mixed results. Would love to hear what’s made donating feel natural rather than forced for your kids.

Your donation strategies help other families navigate this tricky balance too.

References

- Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy – Research on parental modeling and intergenerational giving

- Harvard Business School: Why Giving Makes Us Happy – Conditions that maximize happiness from prosocial behavior

- Harvard Business School: Framing Inequality – How explanation affects children’s sharing behavior

- University of Texas: What Makes People Give – Social network influences on charitable behavior

- NIH: Prosocial Behavior in Children – Developmental research on children’s donation behavior

Share Your Thoughts