Your 7-year-old just watched you drop coins in a donation bucket. “Why do we give our money away?” she asks. And in that moment, you realize you’re about to either plant a seed of genuine compassion—or accidentally water it with guilt.

I’ve navigated this conversation eight times now, with kids ranging from toddlers to teenagers. Here’s what I’ve learned: the how of teaching charity matters as much as the what. Get it right, and you raise a child who gives from genuine joy. Get it wrong, and you create either a resentful giver or someone who donates purely to avoid feeling bad.

Here’s what the research actually shows—and the practical strategies that have worked in my house.

Key Takeaways

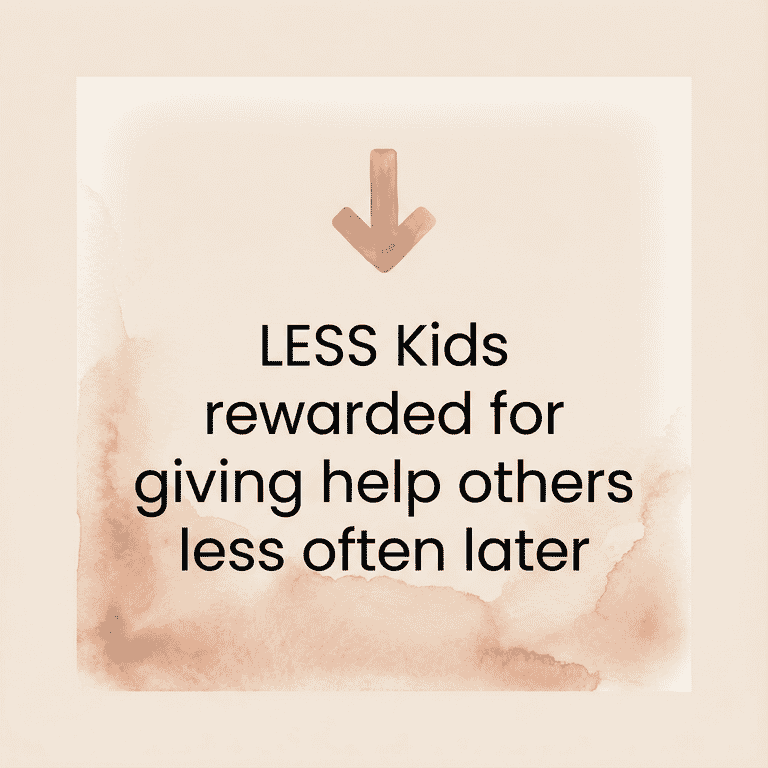

- Material rewards backfire—kids who receive treats for giving actually help others less in the future

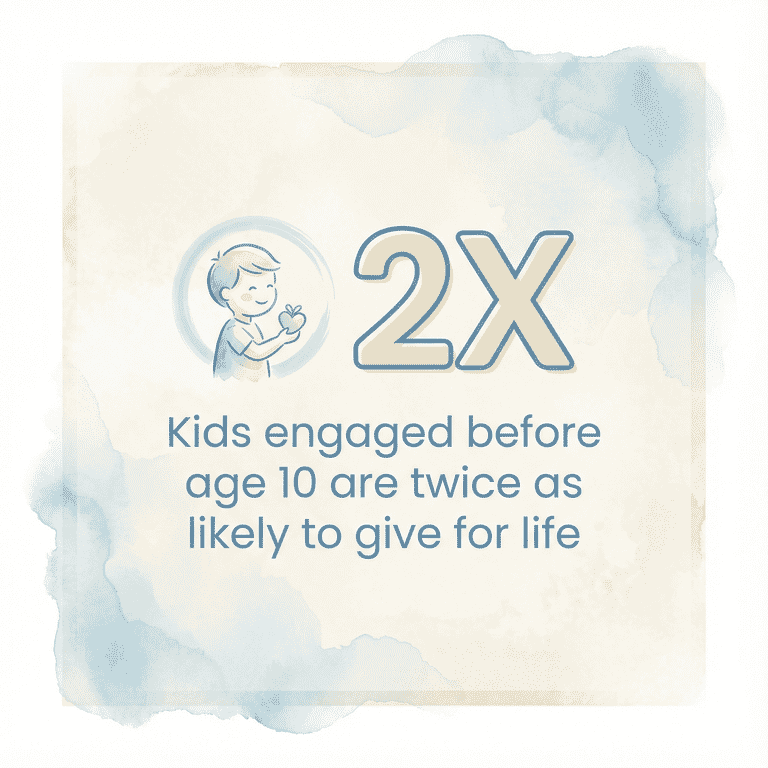

- Children engaged in their first charitable action before age 10 are twice as likely to sustain it throughout their lifetime

- Letting kids choose their causes increases both joy and long-term commitment to giving

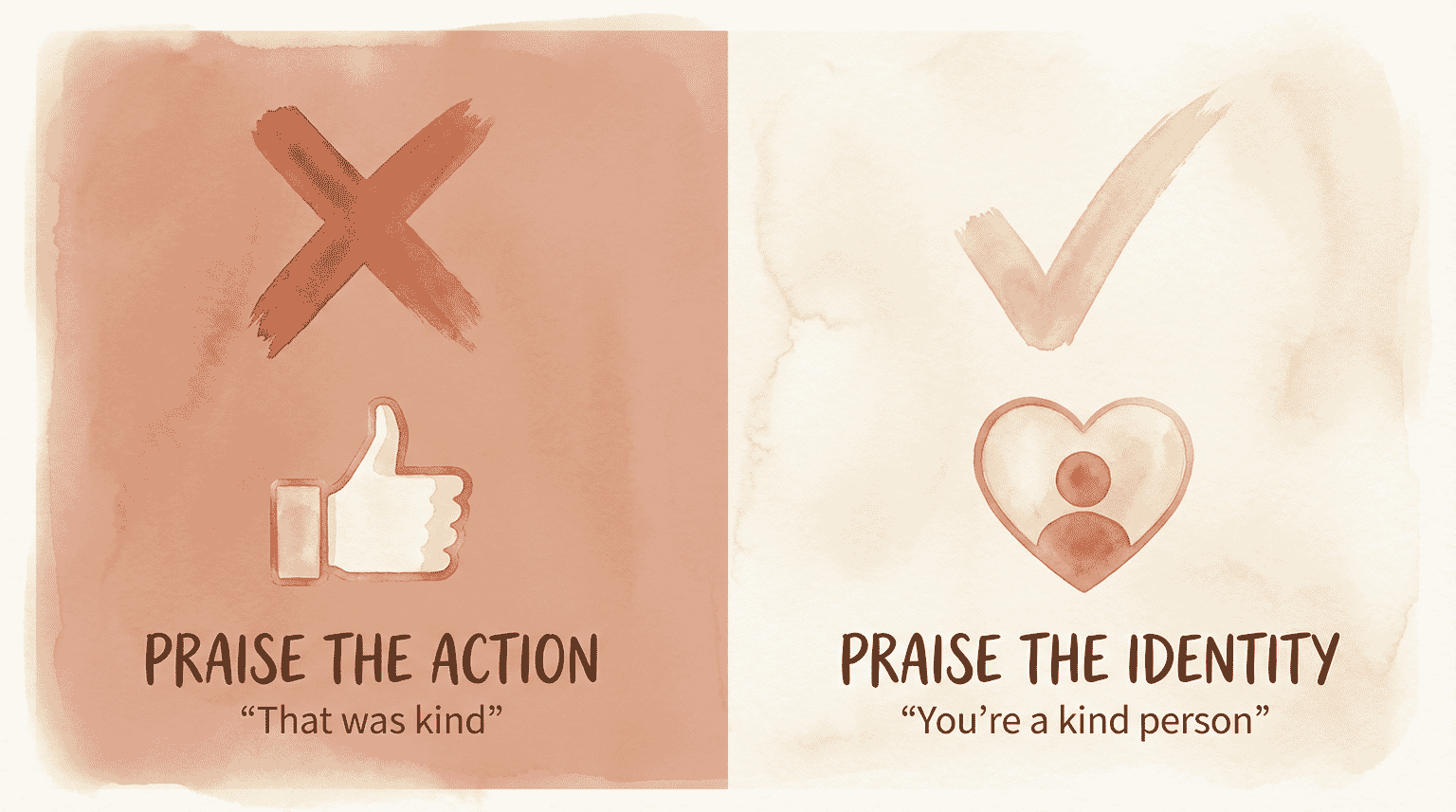

- Praising identity (“You’re a kind person”) works better than praising action (“That was kind”)

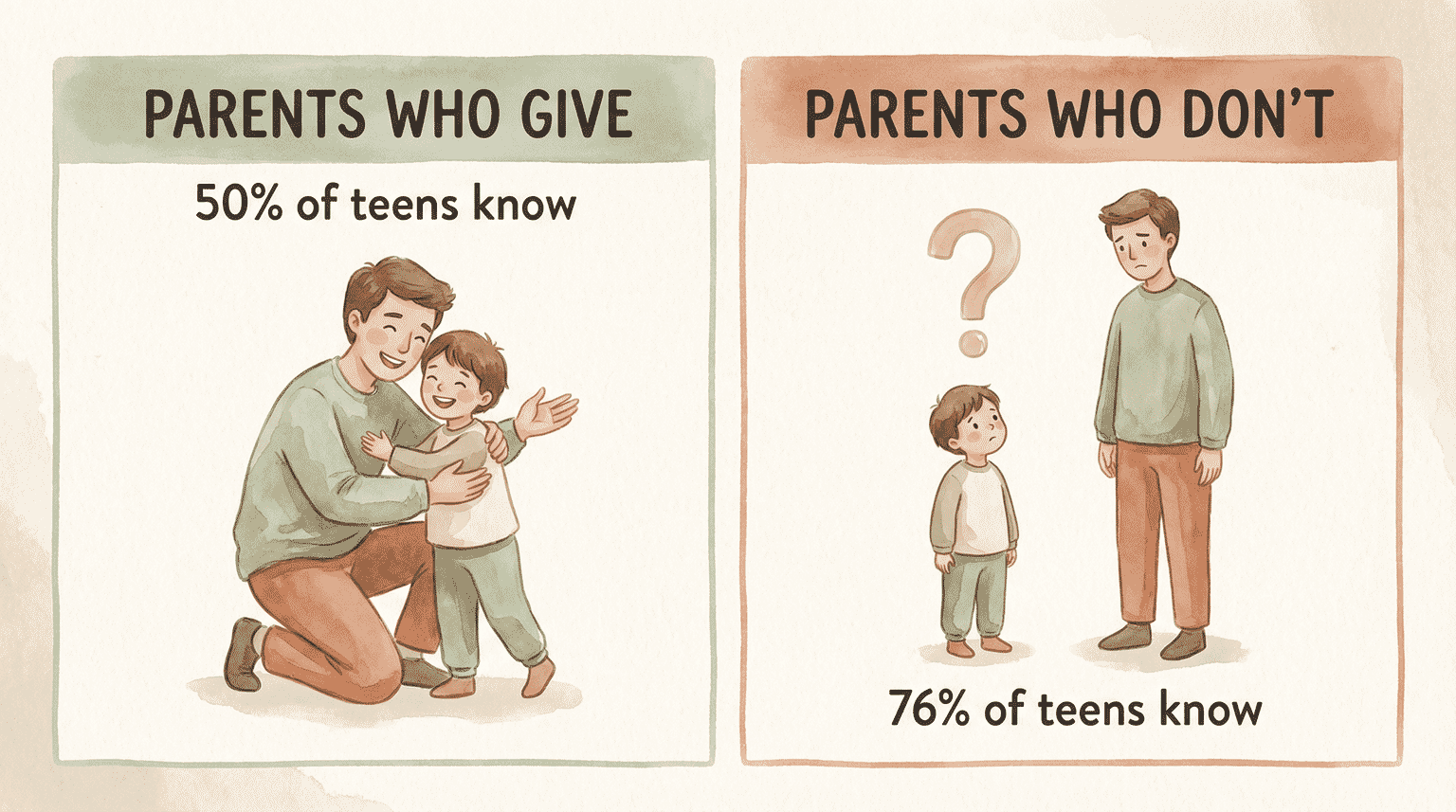

- Silent modeling doesn’t work—you must make giving visible AND discuss it with your children

Why Guilt-Free Matters More Than You Think

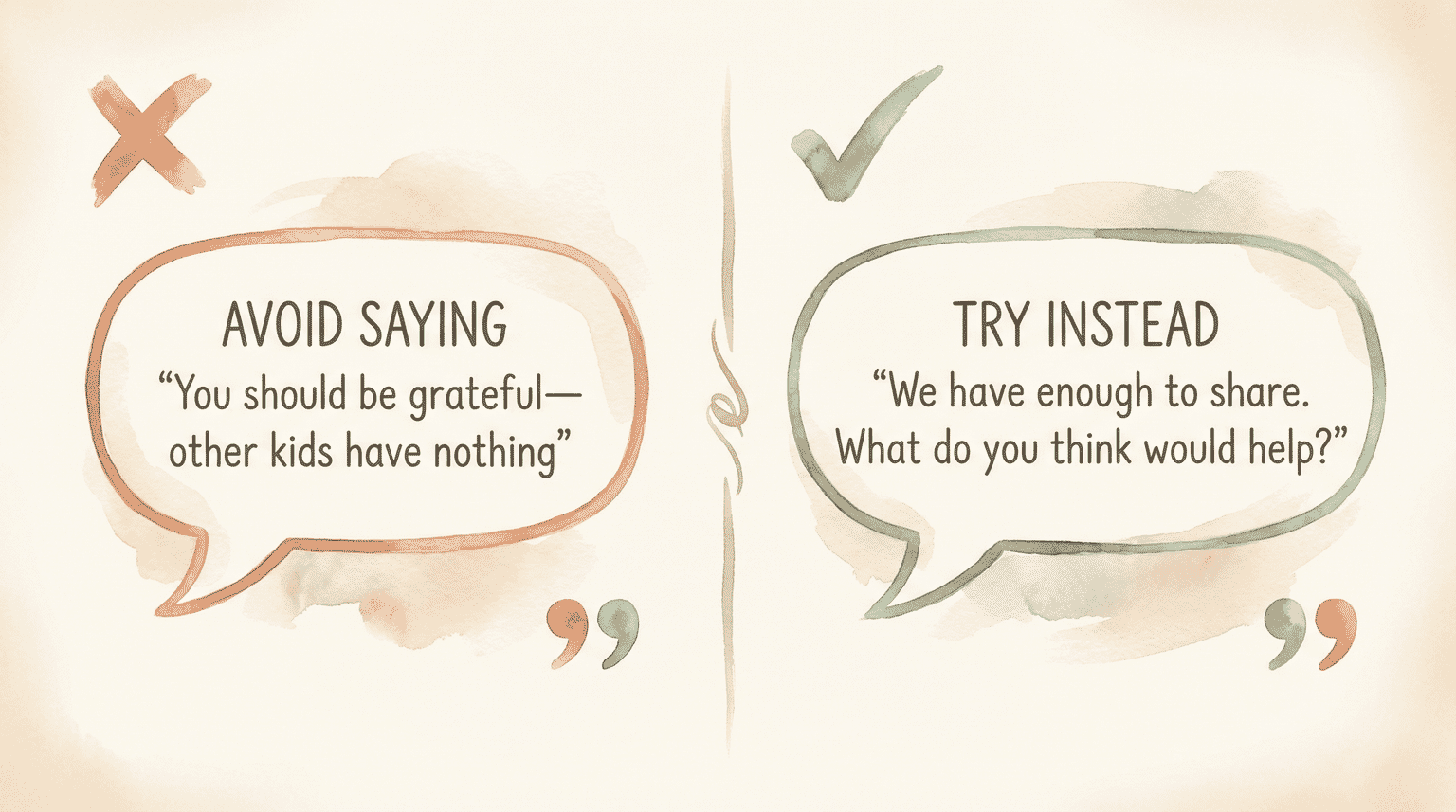

Most parents approach charity education with good intentions and terrible tactics. We lean into phrases like “You should be grateful—other kids have nothing” or “Think about children who don’t have toys.” We mean to inspire empathy. Instead, we accidentally trigger shame.

Research from UC Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center found something that stopped me in my tracks: material rewards for generosity—treats, money, even small gifts—actually reduce children’s future desire to help. Kids who receive tangible incentives offer to help others less than those who receive simple verbal praise or no reward at all.

There’s another problem with guilt-based approaches. Child psychologists describe what happens when we overwhelm children with others’ suffering: they experience “personal distress” rather than empathy.

When emotional arousal becomes too intense, children focus on managing their own discomfort rather than helping others. They shut down instead of opening up.

The goal isn’t charity from obligation. It’s generosity from genuine joy.

Strategy 1: Make Giving Visible (Because Silent Modeling Fails)

Here’s a finding that genuinely surprised me: research shows only about 50% of adolescents know when their parents give to charity. It’s essentially a coin flip. But when parents don’t give? 76% of teens accurately know that.

We assume our kids pick up on our generosity through osmosis. They don’t.

The neuroscience of charitable behavior reveals something parents need to understand about visibility.

“You have to let them know that you are doing it yourself and the child has to see that it is a regular part of the parent’s flow of life.”

— Dr. Mark Wilhelm, Professor of Economics and Philanthropic Studies, Indiana University

What this looks like in practice:

- Write donation checks at the kitchen table instead of setting up silent auto-payments

- Let your child click the “donate” button on your laptop

- Talk through your decisions: “I’m donating to the food bank this month because…”

- If you set up a family donation box system, empty it together and discuss where the money goes

One-time giving barely registers with kids. They need to see it happen repeatedly before it becomes part of their understanding of “what our family does.”

Strategy 2: Let Them Choose (Autonomy Increases Joy)

A 2019 study from the Journal of Experimental Child Psychology uncovered something parents need to hear: when sharing was less obligatory, higher levels of happiness were linked to higher levels of sharing. Force charity participation, and you reduce both joy and long-term commitment. Let children choose, and both increase.

“Giving givers choice—encouraging them to give but allowing them to choose what they give to—can make a big difference in the well-being of the giver afterwards.”

— Kiley Hamlin, Developmental Psychologist

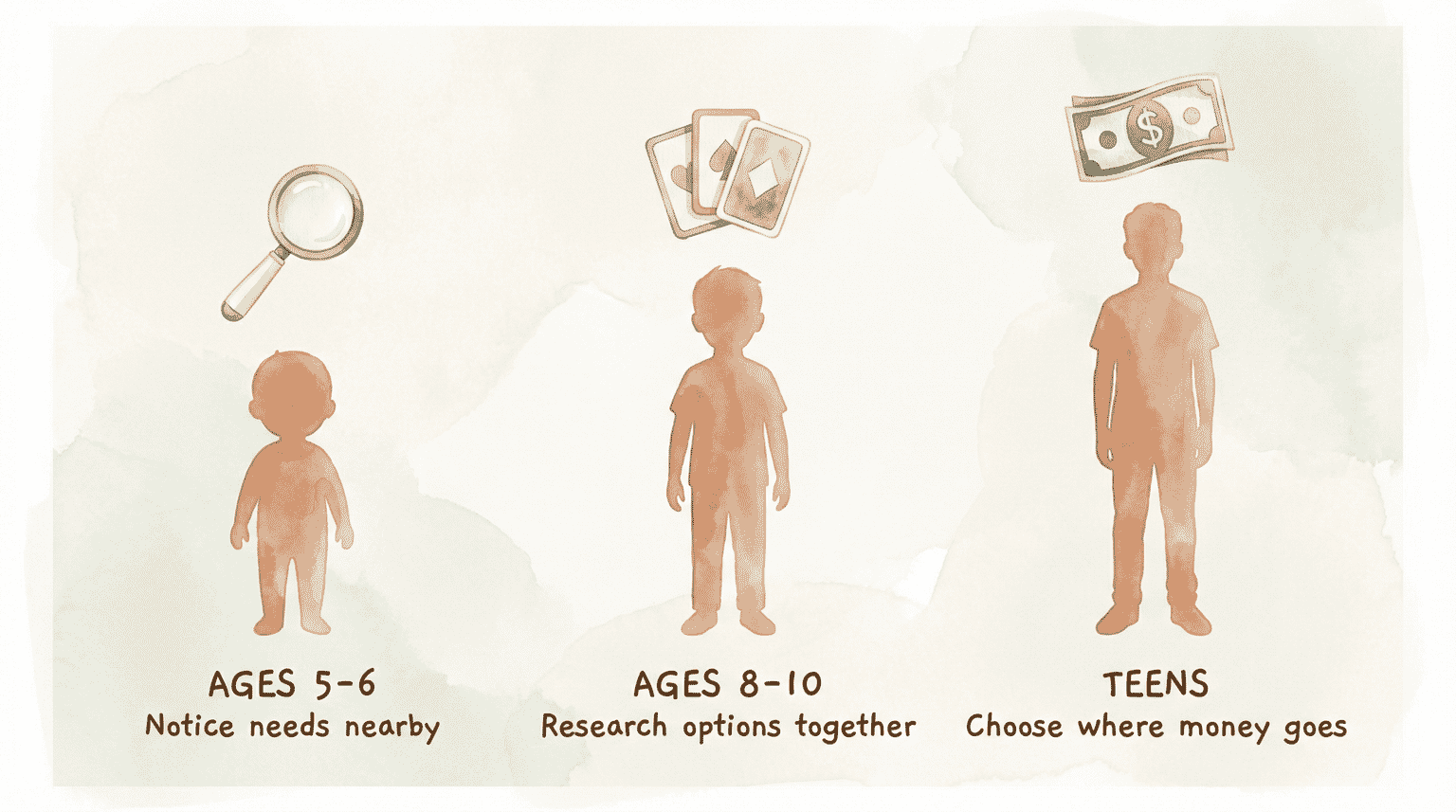

Age-appropriate choice looks like:

- Ages 5-6: “What do you notice in our neighborhood that needs help?” (They might mention stray cats, litter, or a neighbor who seems lonely)

- Ages 8-10: “Here are three organizations. Which one sounds interesting to you? Want to look them up together?”

- Tweens and teens: “You have $20 for giving this month. Where do you want it to go?”

For deeper guidance on matching age-appropriate giving expectations to your child’s developmental stage, the key is starting with their interests. Animal lovers gravitate toward shelters. Sports fans might fundraise for equipment access. Let the cause find them rather than imposing your preferences.

Strategy 3: Talk About It (Actions Alone Aren’t Enough)

I used to think modeling was everything. Then I read the research on parental transmission of charitable values, and my librarian brain had to dig deeper.

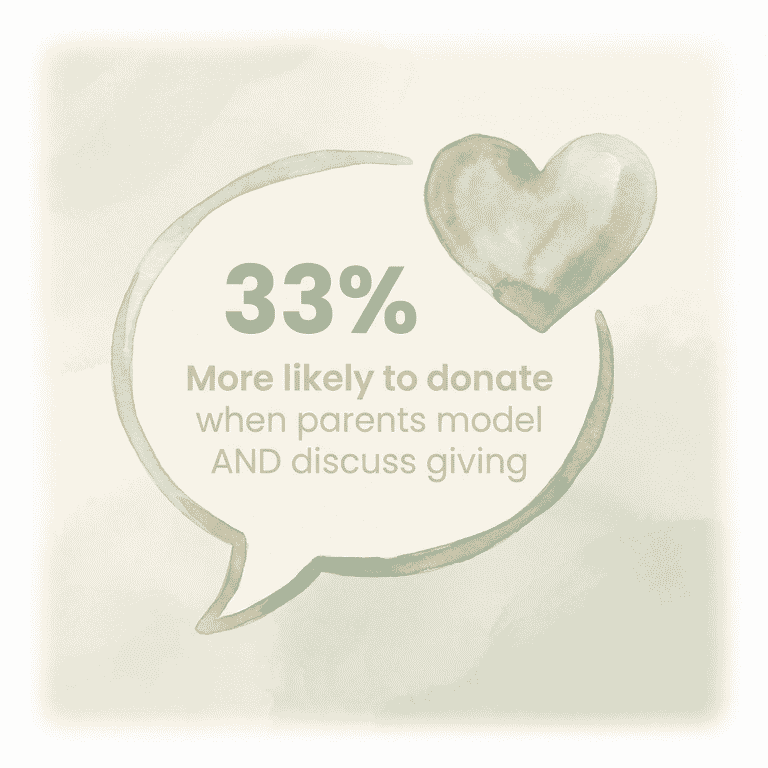

Here’s what I found: adolescents whose parents both model AND discuss giving are 33% more likely to donate compared to teens whose parents only model silently. For volunteering, the effect is even stronger—47% more likely when parents volunteer and talk about why.

The research is clear: actions alone don’t transmit values. Children need to understand the why behind your giving, not just witness the what.

This doesn’t mean lecturing. It means opening conversations that invite curiosity rather than impose guilt.

Research on how children internalize values reveals a surprising truth about communication.

“I think we assume that actions speak louder than words. But in the case of this particular behavior, it seems like you need both together to effectively teach your children generosity.”

— Sara Konrath, Researcher, Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy

Conversation starters that invite rather than lecture:

- “I just read about a family who lost their home in a fire. How do you think they’re feeling?”

- “Our community has a lot of people without enough food. What do you think would help?”

- “Why do you think some people give their money and time to help others?”

The goal is curiosity, not guilt-tripping. Discuss needs without creating anxiety. Explore solutions rather than dwelling on suffering.

Strategy 4: Praise Identity, Not Action

This small shift in language makes a remarkable difference.

When your child shares a toy or drops coins in a donation jar, your instinct might be to say “That was so kind!” Research suggests a better approach: “You’re such a kind person.”

Studies show children praised for being a kind person volunteer more time helping others compared to children praised for working hard to help. The difference is internalization.

The psychology behind identity-based praise explains why this approach creates lasting change.

“They start to internalize it and think of it as part of their identity and their character.”

— Dr. Mark Wilhelm, Professor of Economics and Philanthropic Studies, Indiana University

Phrases that build charitable identity:

- “You really care about other people. I see that in you.”

- “You’re the kind of person who notices when others need help.”

- “That’s so like you—always thinking about others.”

Phrases that accidentally create guilt (avoid these):

- “Other kids would love to have what you have.”

- “You should be grateful—some children have nothing.”

- “Don’t you want to help the less fortunate?”

These comparative statements may motivate short-term compliance but breed resentment or shame over time.

Strategy 5: Make Impact Tangible

Children under 8-10 respond better to identifiable individuals than abstract causes. A 2022 study of Italian schoolchildren found that perspective-taking training increased sharing with specific, identifiable peers—but didn’t automatically translate to donations for anonymous strangers.

What does this mean practically? Young children need to see where help goes.

Ways to make charity concrete:

- Visit the animal shelter where your family donated supplies

- Read a thank-you letter from a sponsored child

- Drop off donations directly rather than mailing them

- Volunteer together at a food pantry and see recipients’ faces

Here’s liberating news for parents worried about “giving enough”: Harvard Business School research examining 600+ Americans found that any act of giving improved happiness—the amount didn’t matter. A child donating one dollar from their allowance experiences the same emotional benefit as major donations. Small actions count.

Strategy 6: Start Early, Build Gradually

Research published in Nonprofit Management and Leadership found that children involved in charitable action before age 10 are twice as likely to sustain it throughout their lifetime compared to those who start at ages 16-18. The early window matters.

The good news? Children are naturally wired for generosity. Foundational research on altruism shows that children as young as 14-18 months demonstrate willingness to help others without expecting rewards.

We’re not creating generosity from scratch—we’re nurturing what already exists.

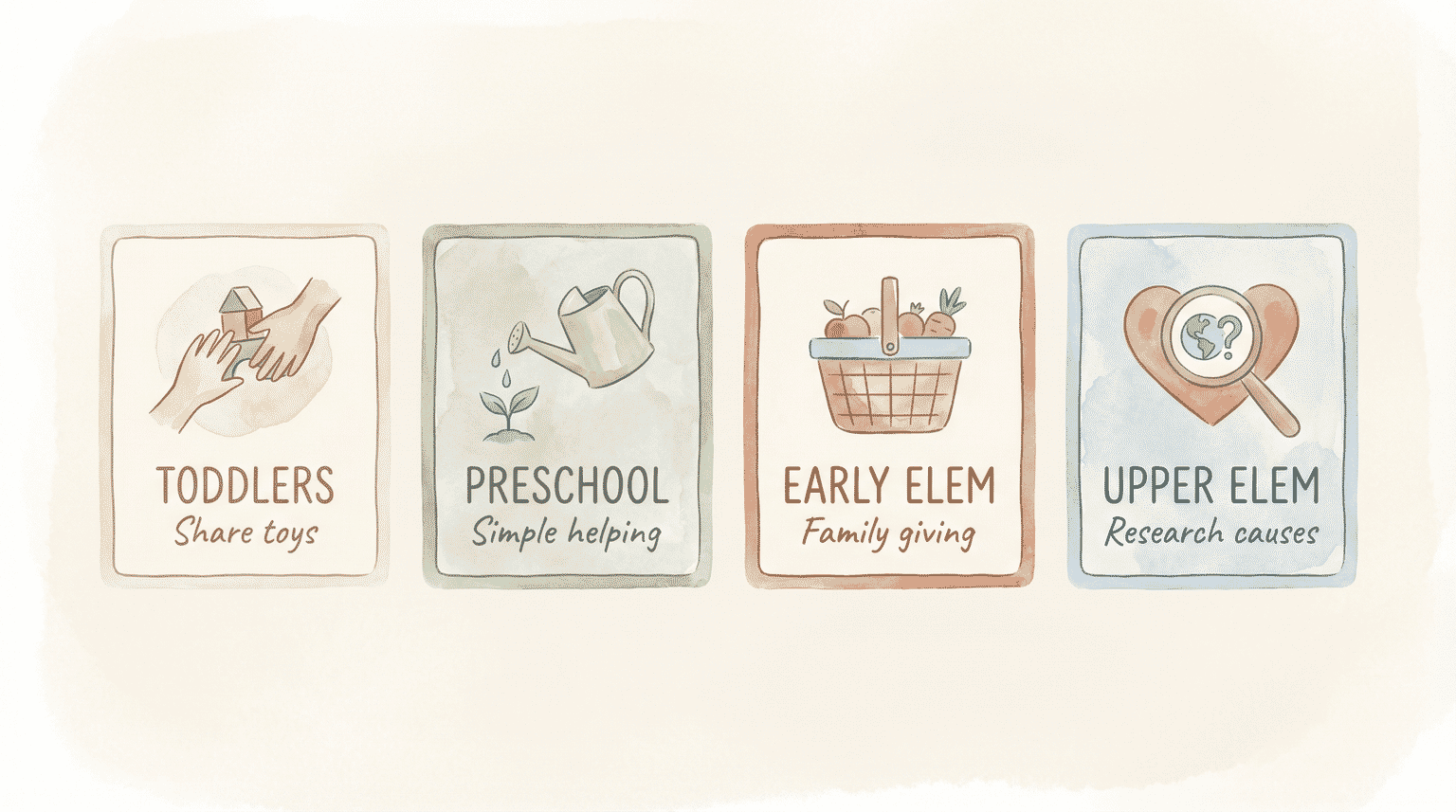

Building blocks by developmental stage:

- Toddlers (1-3): Focus on concrete sharing—”Can you hand that toy to your friend?”

- Preschoolers (3-5): Simple helping tasks with visible results—watering a neighbor’s plants, making cards for nursing home residents

- Early elementary (5-8): Community-focused giving with your guidance—choosing items for food drives, selecting causes from a curated list

- Upper elementary (8-12): Cause selection with research—looking up organizations, comparing options, understanding how donations are used

When thinking about teaching children about meaningful giving, the progression matters more than the amount. Start small, stay consistent, and let complexity increase with age.

Strategy 7: Focus on Joy, Not Obligation

A 2012 University of British Columbia study found that toddlers exhibit greater happiness when giving treats to others compared to receiving them. Let that sink in: giving made them happier than getting.

Even more striking, children were happiest when engaging in “costly giving”—actually forfeiting their own resources rather than giving at no cost. Meaningful sacrifice enhanced rather than diminished their positive experience.

“I think helping our kids experience the happiness that comes from giving to others is probably one of the most valuable ways we can nurture generosity in them.”

— Lara Aknin, Psychology Researcher, Simon Fraser University

Preserving natural joy:

- Never force participation—offer opportunities enthusiastically but respect “not today”

- Celebrate the feeling, not just the action: “How did that feel to help?”

- Frame giving as privilege, not duty: “We get to help” rather than “We should help”

- Notice and name their emotions afterward: “You’re smiling—I think helping made you happy!”

What to Say Instead: A Quick Reference

| Instead of… | Try… |

|---|---|

| “You should be grateful—other kids have nothing” | “We have enough to share. What do you think would help?” |

| “Don’t you want to help the less fortunate?” | “How do you think it feels to need help? What would you want if that was you?” |

| “You have to give some of your allowance to charity” | “If you wanted to use some of your money to help others, what would you choose?” |

| “Think about all the kids who don’t have toys” | “I saw you share with your sister—you really care about people, don’t you?” |

| “It’s the right thing to do” | “When I give, I feel good. Have you noticed that?” |

The shift from obligation to invitation changes everything. Kids can sense when we’re lecturing versus when we’re genuinely curious about their thoughts.

When Resistance Happens (And It Will)

My 6-year-old once refused to donate a single toy to the holiday drive. My instinct was to lecture about gratitude. I’m glad I didn’t. (If you’re struggling with teaching kids to donate toys, resistance is normal.)

Forcing charitable participation backfires. Research shows obligatory giving reduces both happiness and long-term commitment. When children resist, it’s not a character failure—it’s often:

- Developmental: their perspective-taking skills aren’t mature enough yet

- Emotional: they’re overwhelmed by the concept of need

- Practical: the cause doesn’t connect to anything they understand

Responses that preserve future openness:

- “That’s okay. Maybe another time.”

- “Can you tell me what you’re feeling about this?”

- “What would you want to help with, if anything?”

Then drop it. One refused donation box doesn’t predict adult selfishness. Pressure in that moment might.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I teach my child about charity without making them feel guilty?

Focus on joy rather than obligation. Research shows material rewards reduce children’s future helping desire, while letting them choose causes they care about increases happiness. Avoid comparative statements like “others have less than you” and instead frame giving as opportunity: “We get to help because we care.”

At what age should I start teaching kids about giving?

Children show natural helping instincts as early as 14-18 months. By ages 5-6, children can discuss needs they observe in their community. Research shows children engaged in charitable action before age 10 are twice as likely to sustain it throughout their lifetime.

How do you get kids interested in helping others?

Let children choose causes connected to their interests—animal lovers might support shelters, while sports fans might fundraise for equipment access. Make giving tangible and visible rather than abstract. Developmental research confirms that children who choose their own causes experience greater happiness from giving.

Do kids learn charity from parents?

Yes, but only if parents both model giving AND discuss it. Research shows children are 33% more likely to donate when parents do both. Surprisingly, only about half of adolescents know their parents give to charity—silent modeling doesn’t work. You must make giving visible and talk about why it matters.

Share Your Story

How do you talk about charity with your kids? I’d love to hear what’s resonated—and whether you’ve found the balance between teaching compassion and avoiding guilt trips.

Your charity conversations help me understand what works across different families.

References

- UC Berkeley Greater Good Science Center – Research on rewards, praise, and children’s generosity

- United Way of Massachusetts Bay – Studies on voluntary giving and happiness

- Grateful.org/Greater Good Science Center – Parental modeling and discussion research

- Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy – Long-term transmission of charitable values

- Wiley Nonprofit Management and Leadership – Early engagement and lifelong charitable behavior

- The Guardian/Harvard Business School – Psychology of giving and happiness research

Share Your Thoughts