Your 9-year-old is watching a Minecraft streamer unbox the new mystery figure series. Without looking up, she recites: “The rare one is 1 in 24, they drop Friday at 3pm EST, and the purple variant is already sold out.” She knows more about this product line than you know about your car insurance.

Here’s the thing: she’s not being manipulated in the way you might think. What’s happening is actually more sophisticated—and understanding it is the first step toward helping her navigate it.

Key Takeaways

- Children form real emotional bonds with streamers that make merchandise feel like relationship artifacts, not just products

- Mystery box mechanics are designed for escalation—research shows no one buys just one

- The skill children need isn’t avoiding commerce, but recognizing commercial intent from trusted figures

- Five assessment questions can help you evaluate any streamer merchandise request before deciding

Why Your Child Thinks the Streamer Is Their Friend

My librarian brain couldn’t let this one go. When my 12-year-old started referring to a YouTuber as if he’d be coming to dinner, I dove into the research.

What I found has a name: parasocial relationships. These are emotional attachments that form between viewers and media figures based on credibility, familiarity, and perceived accessibility. A 2025 systematic review found that children as young as three recognize brand logos and form these attachments.

Streamers create what researchers call an “illusion of intimacy” through constant camera gaze—that direct eye contact that mimics interpersonal interaction. Your child genuinely feels they know this person the way they know a neighbor or friend.

This is why streamer merchandise isn’t really about the toy. It’s a physical artifact of an emotional bond. When your child asks for that $35 plushie, they’re not just requesting a product—they’re seeking a tangible piece of a relationship that feels real to them.

Understanding how digital culture shapes gift expectations helps make sense of why this generation experiences merchandise differently than we did with our Saturday morning cartoon lunchboxes.

How Streamer Merchandise Actually Works

The psychology behind streamer merchandise operates on three interconnected levels. I’ve watched all three play out in my house—sometimes simultaneously.

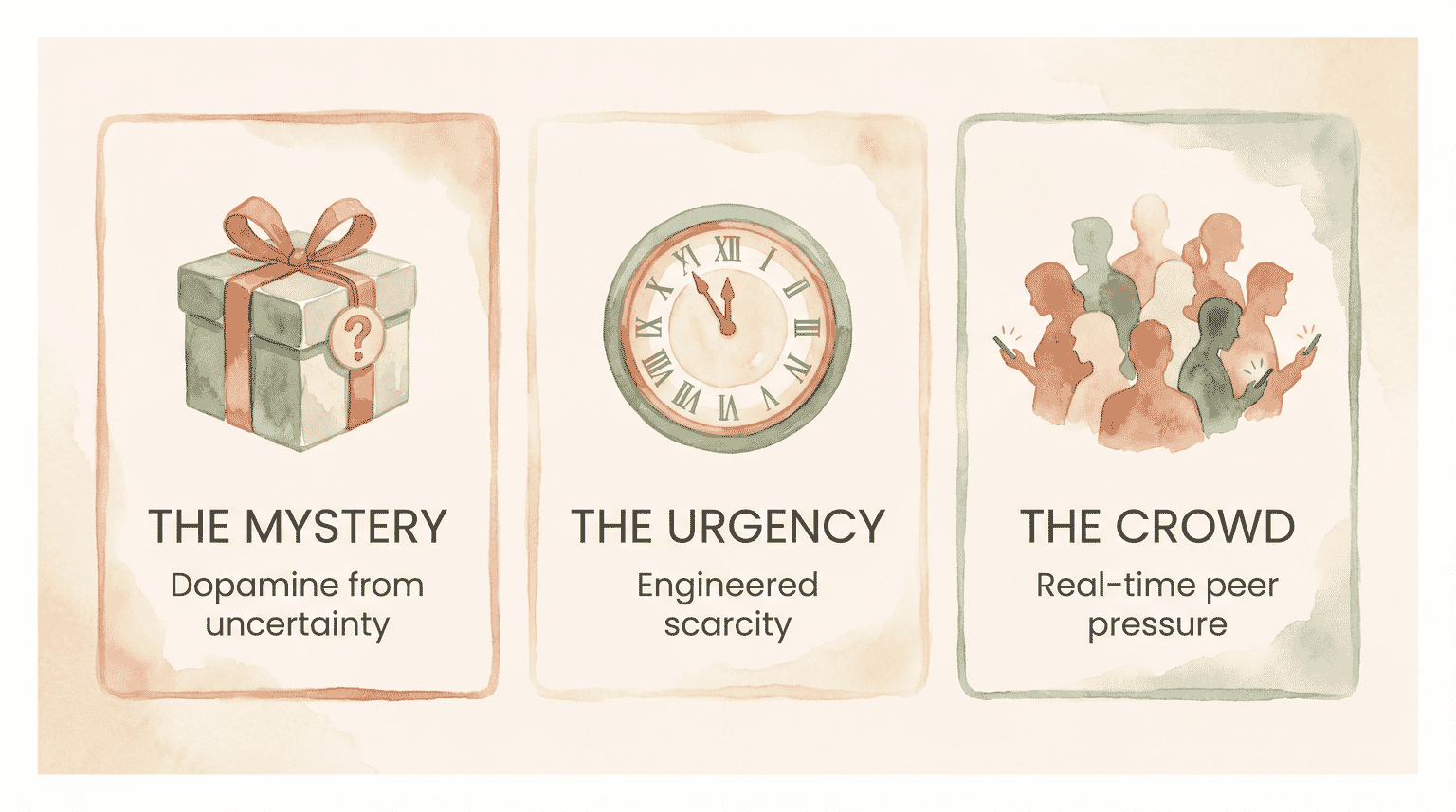

The Mystery Element

Research from 2024 found that over 65% of consumers cite “novelty and surprise” as a key purchasing factor for blind boxes, with 58% specifically attracted by the excitement of style uncertainty.

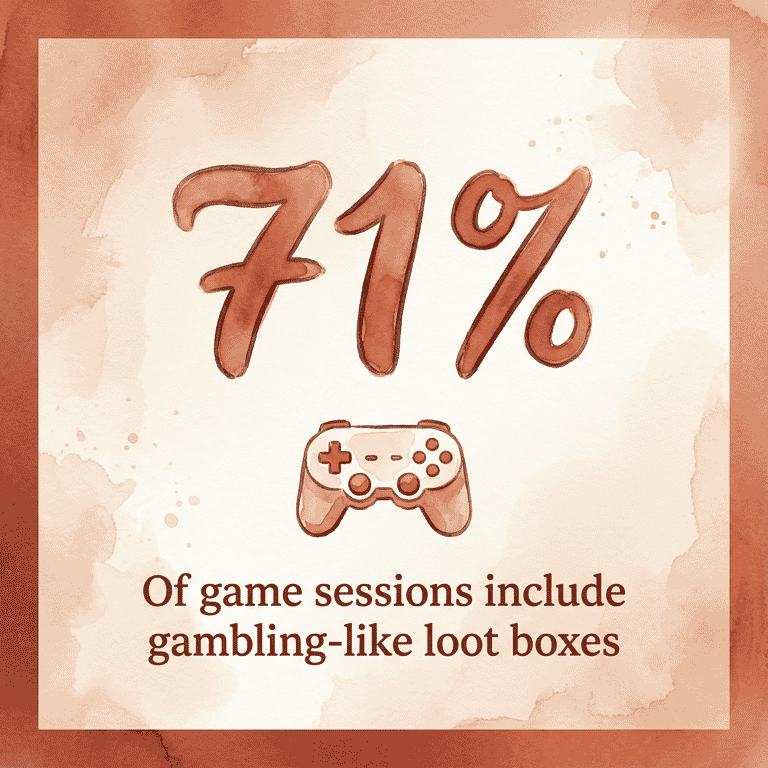

This isn’t accidental product design. The dopamine hit from uncertainty—what will I get?—mirrors gambling mechanics. A 2021 NIH study documented that 71% of game play sessions by 2018 were on games containing loot boxes, and people who purchased them were more likely to experience problem gambling behaviors later.

The Urgency Pressure

Limited editions. Exclusive drops. “Only 500 made.” The FOMO is engineered.

When viewers watch real-time unboxings, they’re experiencing scarcity in action. Someone else is getting the rare one right now. The fear of missing out isn’t irrational from your child’s perspective—it’s a reasonable response to deliberately constructed scarcity.

The Social Proof Loop

Here’s where it gets interesting. A 2022 study found that for experience products like toys, consumers rely more heavily on social influence before purchasing—and live streaming interactions have an outsized impact on purchase intention.

The researchers concluded it becomes “difficult for consumers watching a live stream to resist the temptation of concerted large-scale group action.” When your child sees the chat exploding with purchases, they’re experiencing real-time peer pressure at scale.

This connects to influencer toy reviews and how they shape preferences—the same mechanisms operate whether someone’s unboxing or reviewing.

Why One Purchase Is Never Enough

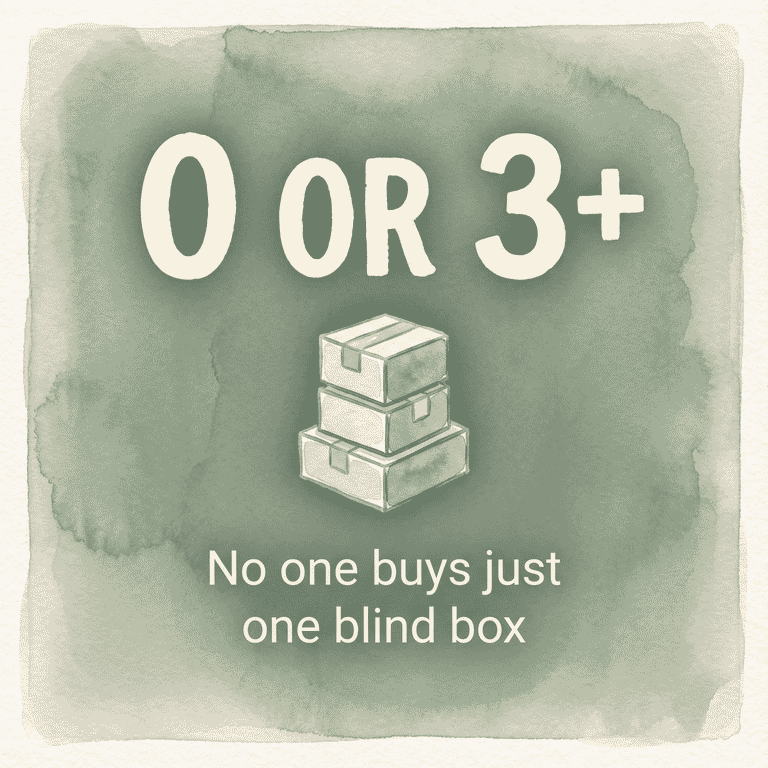

This is the finding that stopped me cold: A 2025 study found that no participants had purchased just one blind box. They either never bought any, or they bought three or more.

Let that sink in. The product structure is designed for escalation, not satisfaction.

The research identified several psychological drivers that keep buyers coming back. Near-miss reinforcement is one of the most powerful. Getting a good-but-not-best item doesn’t discourage purchasing—it reinforces it.

Your child got the blue one, which is nice, but the gold one exists. That “almost” feeling is more motivating than failure.

Illusion of control plays a role too. Your child believes they’ll be the one to get the rare figure. One participant described it: “It’s like just the excitement, maybe a bit psycho, maybe, the risk taking is the best part for me.”

Then there’s the set completion drive. Over 70% of consumers report feeling great accomplishment when completing collections. The 40% repeat customer rate is built into the business model.

As one research participant explained: “After I started to collect those, I kept going to POP-MART and kept seeing all these cute little dolls. Yeah, just kept expanding the things I’m collecting. It’s just hard to resist.”

I’ve seen this with my 10-year-old. One figure became four, then “just one more to complete the set,” then a new series launched.

Why Children Are Particularly Vulnerable

The research is uncomfortable here. The 2025 systematic review stated plainly: “The evidence does suggest that marketing has the biggest effect on the most vulnerable.”

Children face compounded vulnerability:

- Developmental inability to fully recognize commercial intent, especially from trusted figures

- Parasocial bonds that reduce critical evaluation of recommendations

- Peer pressure amplified in real-time streaming environments

- Experience products (toys, games) showing greater susceptibility to streaming influence than other categories

At an industry conference, an insider described esports events as “the training ground for future wagerers.” That’s not paranoia—that’s documented marketing strategy.

Research found that 28% of users responding to esports gambling tweets were children under 16. The audience isn’t accidental.

What Parents Can Actually Assess

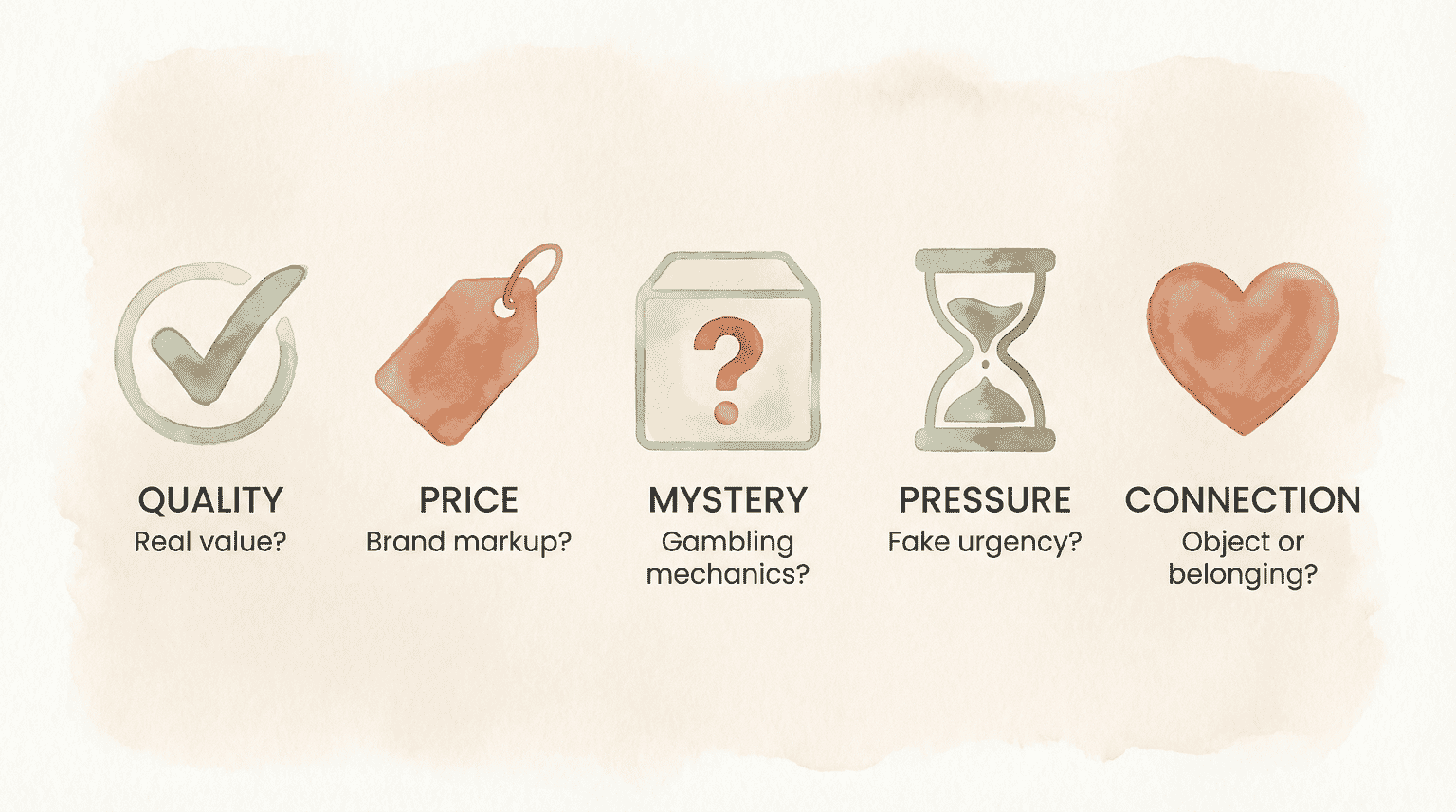

Here’s where I shift from explaining to making toy purchasing decisions you can actually use. Five questions to ask before any streamer merchandise purchase:

1. Quality question: Is this substantially different from non-branded alternatives? Many streamer plushies use identical manufacturing as generic products at half the price.

2. Value question: What’s the markup for the brand association alone? Sometimes it’s reasonable. Sometimes it’s 400%.

3. Mystery question: Does this product use uncertainty mechanics? Blind boxes, mystery variants, limited editions with random allocation—these are red flags for escalation patterns.

4. Pressure question: Is the purchase being driven by urgency or scarcity messaging? “Only available today” is a marketing tactic, not a deadline.

5. Relationship question: Does my child want the object or the connection it represents?

That last question matters most. Sometimes the answer is genuinely “the object.” But often, the merchandise is a proxy for belonging—to the creator’s community, to friends who also watch, to the relationship itself.

Talking to Children About Streamer Marketing

My approach with my kids has evolved from “no” to “let’s think about this together.”

“I can see how much you love watching them. They’re also selling products to people who watch. What makes this worth $X to you?”

— Sample parent response when your child says “I need the new mystery box!”

Validate the relationship first—it’s real to them. Then name the mechanism without being preachy: They’re a creator, and they also sell stuff.

Ask questions rather than lecturing. “What would happen if you got the common figure instead of the rare one?” “How would you feel in a week?” Children can often identify the temporary nature of the excitement when given space to think.

The key insight: Children can’t naturally recognize commercial intent from trusted figures. Your role isn’t to forbid—it’s to illuminate what they can’t see yet.

The Bottom Line

Streamer merchandise isn’t inherently harmful. My 15-year-old has a few creator items she genuinely treasures. But the psychology is more sophisticated than parents realize.

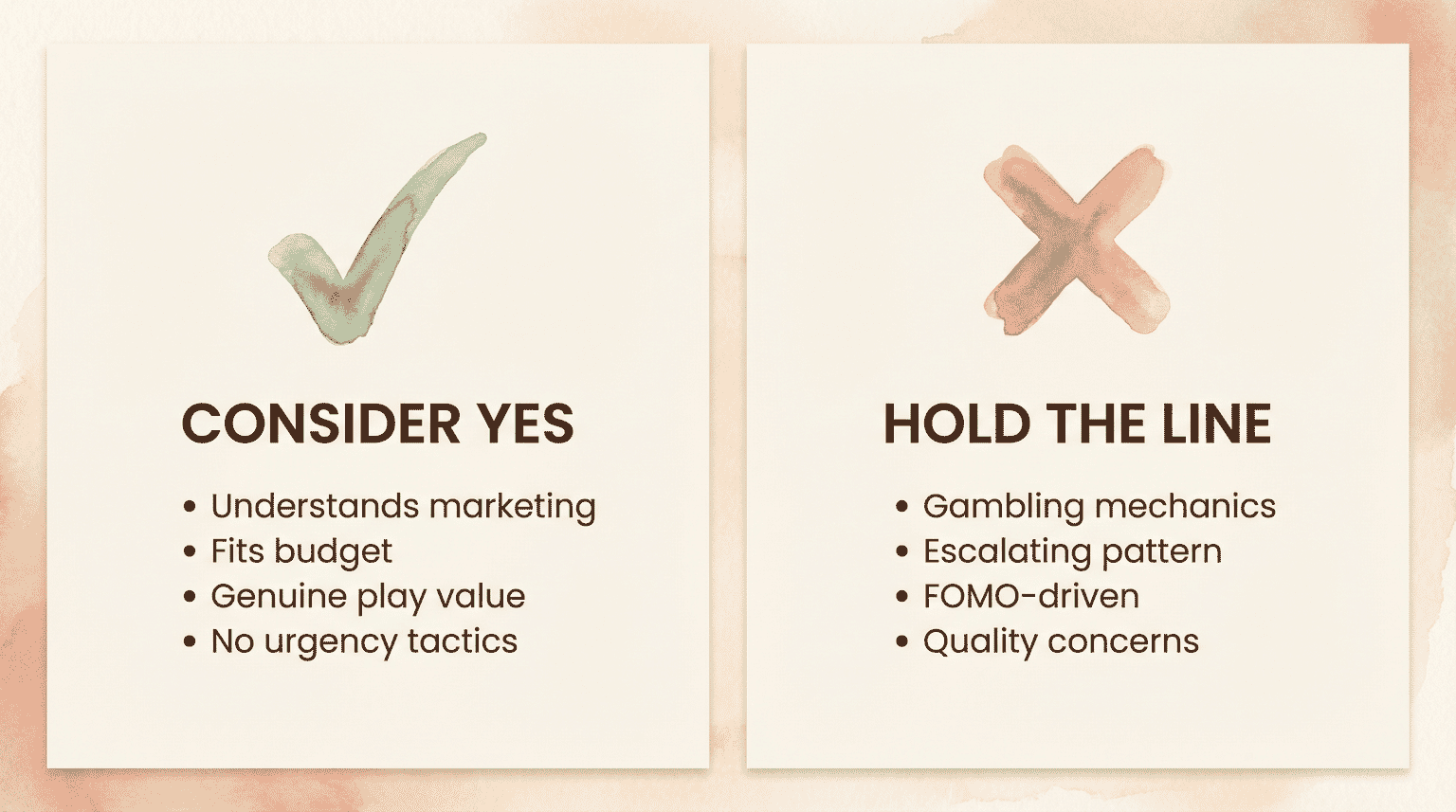

When to consider saying yes:

- Your child understands the marketing dynamic

- Purchase fits family budget without tension

- Product has genuine play or display value beyond status

- Not driven by urgency, scarcity, or mystery mechanics

When to hold the line:

- Gambling-like mechanics are the primary appeal

- Escalating purchase patterns are emerging

- Fear of missing out is driving the request

- Quality concerns about the specific product

Your child’s interest in streamers is developmentally normal. They’re forming connections in a digital landscape that didn’t exist when we were kids. Your job is to help them navigate the commercial layer that’s been carefully engineered on top of those genuine relationships.

Frequently Asked Questions

At what age can children understand streamer marketing?

Children as young as three recognize brand logos, but understanding commercial intent develops much later—often not until middle school, and even then, applying critical thinking to trusted figures like favorite streamers remains challenging without adult guidance.

Why does my child know every detail about merchandise drops?

Streaming platforms create immersive environments where product information is embedded in entertainment. Your child absorbs release dates, prices, and variant details through repeated exposure during content they enjoy—it’s incidental learning with commercial outcomes.

Should I ban my child from watching streamers who sell merchandise?

Banning is rarely effective and misses the teaching opportunity. Most successful content creators monetize through merchandise. The skill children need is recognizing commercial intent within trusted relationships, not avoiding all commerce.

Is collecting streamer merchandise different from collecting other toys?

The collecting impulse is the same, but the mechanics differ. Blind boxes, artificial scarcity, and parasocial leverage are deliberately designed to escalate purchases beyond collecting into compulsive buying patterns.

Share Your Story

Has your kid asked for streamer merchandise or mystery figures? I’d love to hear how you’ve handled the requests—and whether any conversations about persuasive intent have actually landed.

Your streamer merchandise stories help other parents decode this world too.

References

- When Games and Gambling Collide (NIH, 2021) – Research on gambling-like mechanics in gaming

- Marketing by Live Streaming (PMC, 2022) – How streaming interactions drive purchase behavior

- Psychological Analysis of Blind Box Craze (DR Press, 2024) – Consumer psychology of mystery merchandise

- Brand Marketing Impact on Children (PMC, 2025) – Systematic review of marketing effects on young audiences

- Blind Box Consumption Psychology (Current Psychology, 2025) – Qualitative study of purchasing patterns

Share Your Thoughts