Your calendar is packed. Soccer practice, piano lessons, a tutor for reading, and maybe—if there’s time—a playdate with structured activities. Meanwhile, your child hasn’t said “I’m bored” in weeks. That sounds like success, right?

Here’s what the research actually shows: you might be engineering imagination right out of your child’s day.

Key Takeaways

- Imagination is a learnable skill that strengthens with practice—not a fixed gift some kids have and others don’t. (Try construction toys.)

- Boredom is the doorway to creativity, not a problem to solve—complaints of “nothing to do” often precede the most inventive play

- Screen time duration matters less than who chooses content and who plays alongside your child

- At least 2 hours weekly of nature exposure significantly boosts creativity compared to manufactured play settings

- Fewer toys and more constraints actually focus creative energy—a child with 3 toys plays deeper than one with 40

The Problem No One Wants to Name

We’ve been sold a story that more activities mean more development. More enrichment equals more prepared kids. But a 2023 study published in PMC found something that stopped me in my researcher tracks: imagination requires “separation from the mundane, or day-to-day routines and demands” to actually function.

That separation? It’s exactly what our packed schedules eliminate.

The same research identified imagination as “key to survival—a component of resilience that enables us to develop ideas, competencies, and strategies to resist or change challenging conditions.” This isn’t about making nice paintings or playing pretend. It’s about raising kids who can adapt, problem-solve, and envision possibilities that don’t yet exist.

Yet as Harvard developmental psychologist Paul Harris observes:

“Once we move away from the preschool… the idea that children could learn simply by exercising their imagination is rarely something that’s deployed.”

— Paul Harris, Developmental Psychologist, Harvard Graduate School of Education

In my house, with eight kids spanning ages 2 to 17, I’ve watched this play out repeatedly. The schedule gets full, the “productive” activities multiply—and the wild, weird, wonderful imagination play disappears. Not because my kids lost their capacity for it. Because we stopped leaving room for it.

How Imagination Actually Works

Here’s something my librarian brain couldn’t let go: we talk about imagination like it’s a mystical gift some kids have and others don’t. The research tells a different story.

According to the National Library of Medicine, imagination is “a process of the mind somewhere between cognition, recall, and play.” It operates at the intersection of what we know, what we remember, and what we can playfully recombine. And critically, it’s “a talent that can be learned and refined over time.”

Imagination isn’t a gift. It’s a muscle.

The 2023 PMC research reinforced this with two powerful metaphors: imagination as a “muscle” that strengthens through regular exercise, and imagination as a “gift” that requires active use to maintain.

Both metaphors point to the same truth—imaginative capacity is developable, not fixed. Like any skill, it grows with practice and atrophies without it.

What’s fascinating is how reality-bound children’s imagination actually is. Harvard’s Paul Harris explains that children’s pretend play is “reality bound enough for it to help them think through situations.” When my 4-year-old hosts a tea party for stuffed animals, she’s applying everything she knows about liquids, containers, and social interaction. She pours from the spout. She waits for it to “cool.” She passes cups without spilling.

This isn’t escapism. It’s rehearsal. Research shows that when 3-year-olds are asked to “stop and think” and imagine outcomes before acting, they predict results more accurately than when answering immediately. Imagination helps children process reality, not escape it.

The Boredom Mechanism

“Mom, I’m bored.”

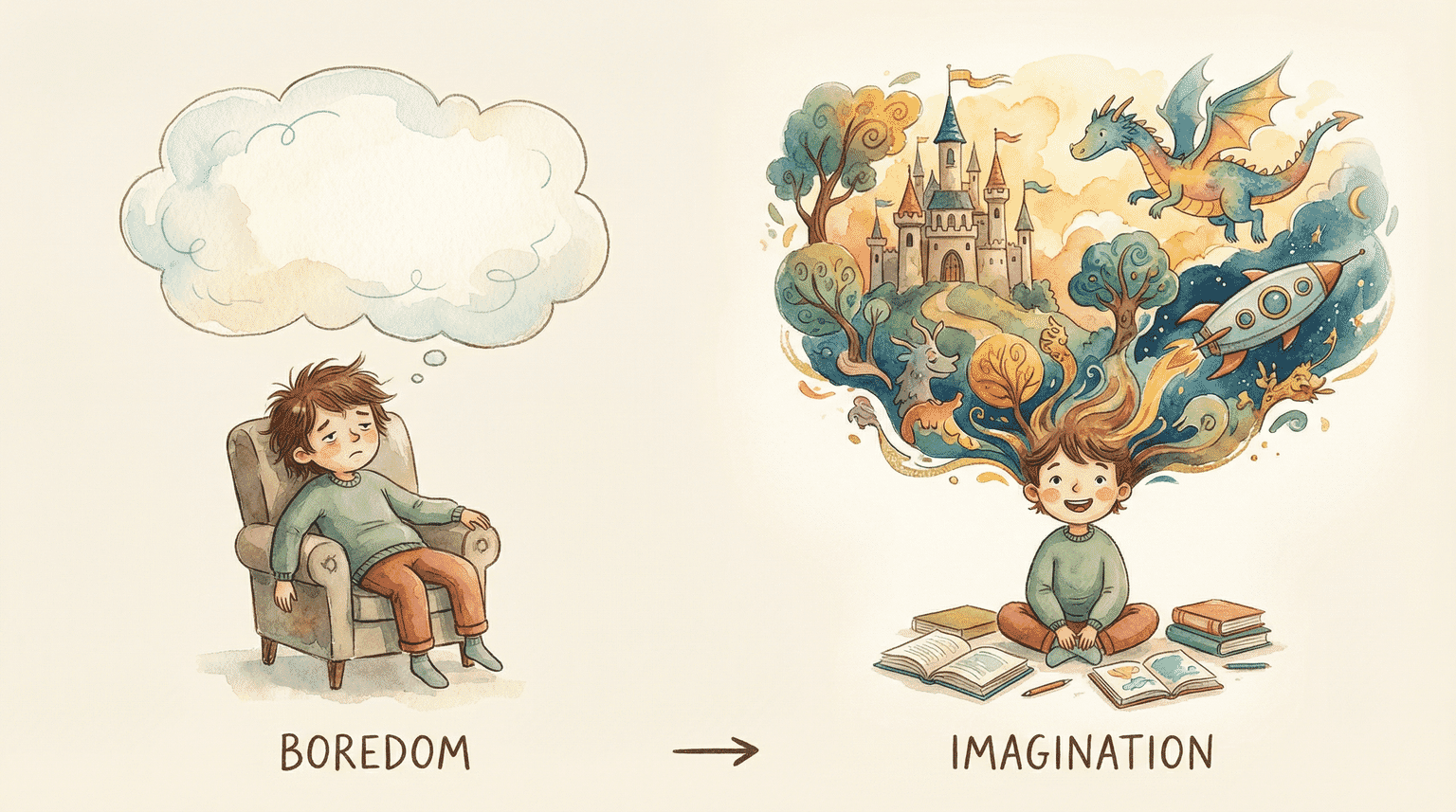

I used to hear that as a problem to solve. Now I recognize it as the sound of imagination warming up.

Research distinguishes between “spontaneous imagination”—the playful, emergent kind—and “controlled imagination”—the purposeful, directed kind. Spontaneous imagination is where novel ideas come from. It’s also the kind that requires what researchers call “a measured, slower pace” to emerge.

You can’t schedule spontaneous imagination. You can only create conditions where it has space to appear.

When children’s time is completely filled, the mechanism that generates creative thinking has no opportunity to activate. It’s like expecting plants to photosynthesize in a windowless room—you’ve eliminated the essential condition.

In my house, I’ve watched this countless times. The complaints of “there’s nothing to do” almost always precede the elaborate blanket fort, the invented card game, the spontaneous puppet show. The boredom isn’t the problem. The boredom is the doorway.

The Constraint Paradox

Here’s where the research gets counter-intuitive. More isn’t better. In fact, the 2023 PMC study found that “something less than pure freedom can enrich imagination.”

Constraints actually focus creative energy.

This matches what I’ve observed across eight kids and a thousand-plus gifts: the child with forty toys plays with none of them. The child with three plays deeply and inventively with all of them. If you’re curious about the research on fewer toys and deeper play, the findings are consistent—limitation creates the friction imagination needs to ignite.

Think of it like this: unlimited options create decision paralysis. A few interesting materials create a puzzle to solve.

A cardboard box, some markers, and nothing else becomes a spaceship, a house, a turtle shell, a time machine. The magic isn’t in the materials. It’s in the constraint itself.

Why Environment Matters More Than You Think

Physical space sends signals. When children enter a space that looks different, feels different, operates by different rules, their brains shift modes. This is why dedicated play spaces—even a corner of a room—can activate imagination in ways that scattered toys throughout the house cannot.

But not all environments are equal. A 2024 scoping review in Educational Psychology Review examined 45 studies on nature and creativity. The findings were striking: children in environments with natural materials showed significantly improved creativity, problem-solving, and focus compared to manufactured settings.

Why? The researchers point to what they call “soft fascination”—the effortless attention that natural settings capture. Unlike manufactured toys designed to demand attention, natural environments gently engage the senses while leaving cognitive space for creative incubation.

One teacher observed children in natural outdoor play:

“You could see they could feel the sounds in their bodies. And the senses, just being outside… you could see them getting into it.”

— Teacher observation from nature-creativity study, 2024

The review found that at least two hours weekly of nature exposure is necessary for creativity benefits, with more immersive experiences outperforming indoor plants or window views.

Children preferred natural play zones because of the diversity of raw materials and open-ended possibilities—while manufactured zones were described as “predictable” and “tedious.”

The Screen Time Mechanism (What Actually Matters)

This one surprised me.

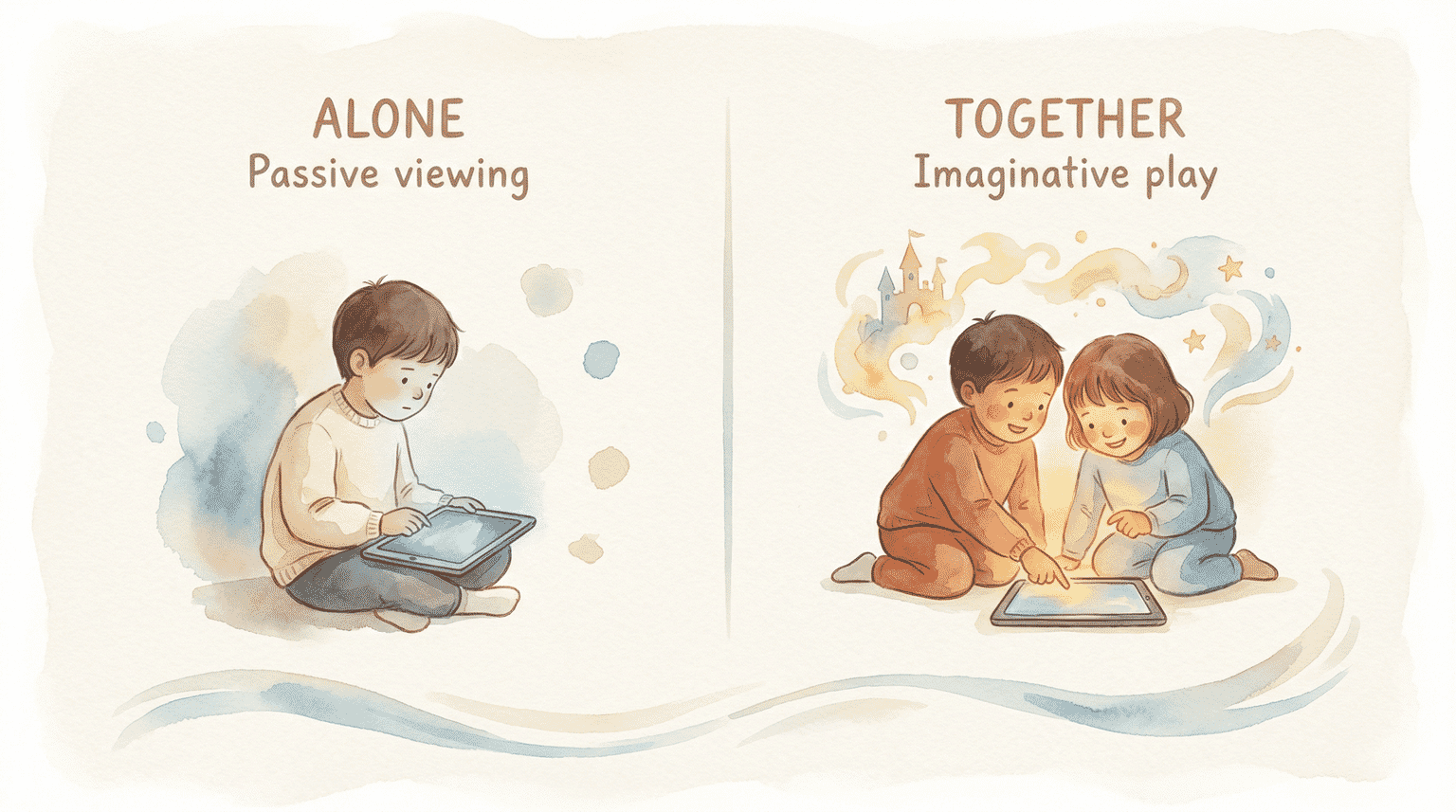

A 2023 study of 772 families found no relationship between time spent on screens and imagination levels. Let that sink in. Duration wasn’t the variable that mattered.

What did matter? Two things: who chooses the content and who plays alongside the child.

Children who selected their own content showed significantly higher imagination elaboration scores than those whose content was chosen by adults. And imagination flexibility scores were highest in children who played with siblings or peers rather than alone or with adults.

The researchers explain that peer play requires negotiation—children must agree on rules, share control, improvise together. This social friction trains exactly the cognitive functions that support imagination. Adults, well-meaning as we are, tend to take observer positions rather than engaging as equal participants.

The practical takeaway isn’t “ban screens.” It’s “attend to autonomy and social context.”

Resisting the Enrichment Pressure

Here’s the permission I needed to hear, and maybe you do too: the research doesn’t support our anxious stacking of enrichment activities.

What the research supports is imaginative play itself—the kind that happens when children have space, materials, and freedom to direct their own experience.

As Paul Harris notes, imagination is “a source of pleasure for children” that remains undervalued as a learning tool. The pretend tea party, the elaborate block construction, the invented world with its own rules—these aren’t breaks from learning. They are learning.

I’ve watched my 15-year-old help my 4-year-old build an elaborate “zoo” out of couch cushions and stuffed animals. No curriculum. No outcomes. No adult-designed enrichment. Just two siblings separated by a decade, co-creating a world according to rules they invented together.

That’s imagination working exactly as it should.

Creating the Conditions

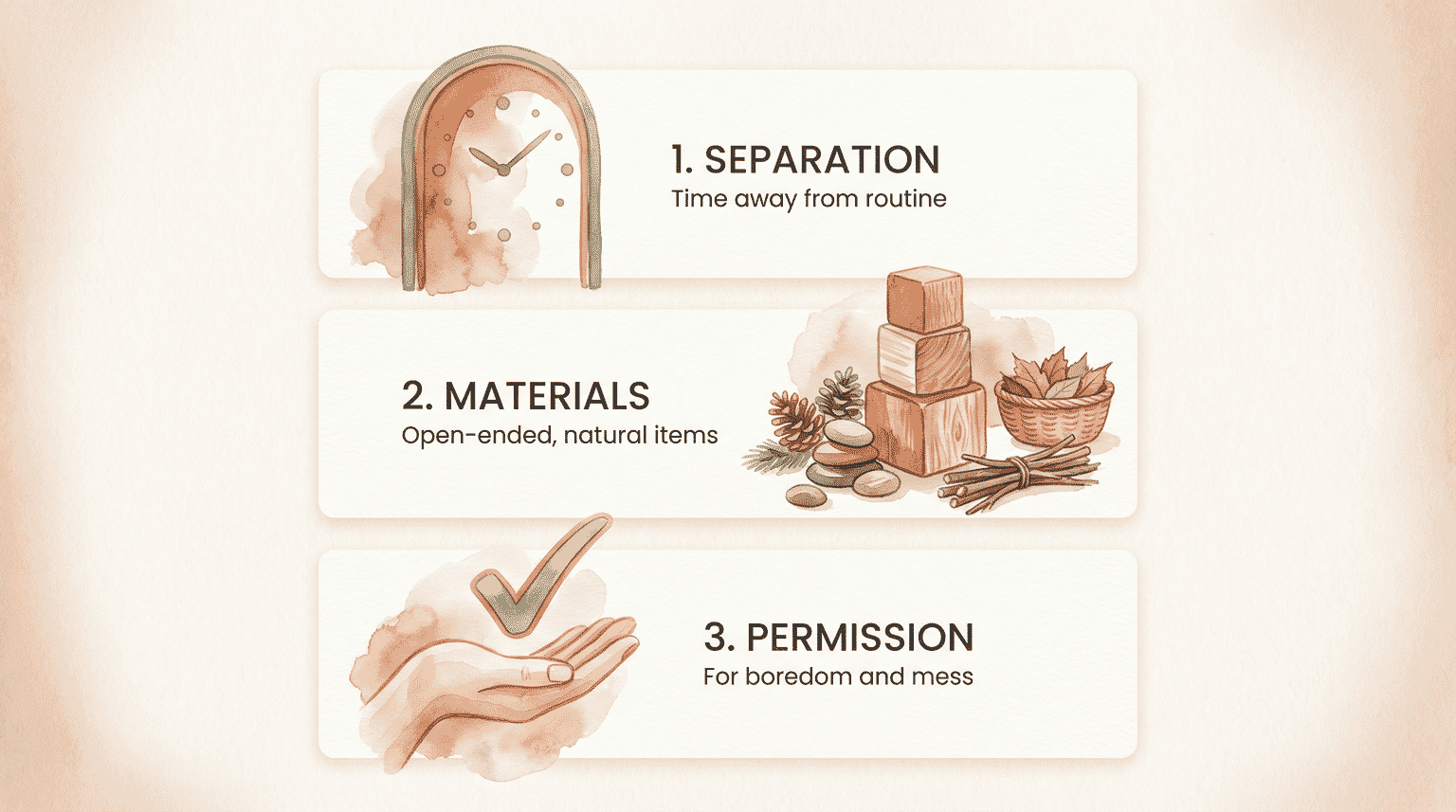

Based on what the research shows, imagination needs three things:

Separation: Time and space that feel different from the mundane. This could be a dedicated play area, an afternoon without scheduled activities, or simply ten minutes where you deliberately stop directing.

Materials: Not more materials—better ones. Natural, open-ended, combinable. Blocks, scarves, boxes, sticks. Things that can become anything rather than things designed to be one thing only.

Permission: Both yours and theirs. Permission for boredom. Permission for mess. Permission for play that looks like “nothing” but is actually everything.

If you’re thinking about gifts that align with your family’s values, this framework helps. The goal isn’t finding the perfect imagination-sparking toy. It’s creating the conditions where any materials become fuel for creative thinking.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does screen time actually damage children’s imagination?

Research suggests duration isn’t the key variable. What matters more is whether children choose their own content and whether they have social partners in play. A 2023 study found no relationship between time spent on screens and imagination levels—but significant relationships between autonomy, social play, and imaginative capacity.

Why does boredom help creativity?

Boredom creates the mental separation from routine that imagination requires to activate. Research distinguishes between spontaneous imagination (emergent, playful) and controlled imagination (directed, purposeful). Spontaneous imagination—the source of novel ideas—requires unscheduled time to emerge.

How much unstructured time do children need?

Research doesn’t specify exact amounts, but the consistent finding is that more immersive, self-directed experiences outperform brief or adult-structured ones. For nature exposure specifically, at least two hours weekly shows creativity benefits. The key is regularity and genuine freedom, not duration alone.

What if my child just complains during unstructured time?

That’s the mechanism working. The discomfort of boredom often precedes imaginative engagement. Rather than solving the boredom immediately, try waiting. What emerges from “there’s nothing to do” is often more creative than any activity you might have suggested.

What About You?

How do you create space for imagination in your family? I’m curious whether you’ve intentionally left gaps in the schedule—and what emerges when boredom has room to breathe.

Your boredom stories might be exactly what another overwhelmed parent needs to read.

References

- Applied Imagination – PMC (2023) – Research on imagination as learnable capacity and conditions that support it

- Nature-Creativity Connection – Educational Psychology Review (2024) – Scoping review of 45 studies on nature exposure and creativity

- Active Screen Time and Imagination – PMC (2023) – Study of 772 families examining screen time and imaginative capacity

- The Nature of Imagination – Harvard EdCast (2022) – Paul Harris interview on developmental psychology of imagination

- Imagination: The Cornerstone of Innovation – NLM (2021) – Framework for imagination as developable capacity

Share Your Thoughts