Your 3-year-old is melting down. Not because she’s tired or hungry—because you turned off the iPad. You’ve tried transition warnings. You’ve tried timers. You’ve tried that calm voice the parenting books recommend. Nothing works.

Here’s what my librarian brain couldn’t let go: Why do some families navigate screen endings without tears while most of us brace for impact? I dug into the research expecting to find better transition strategies. What I found instead completely reframed how I think about gift decisions.

Key Takeaways

- Children who can sustain physical play have 37% fewer screen time tantrums—play capacity matters more than executive function skills

- The 10-minute test reveals whether your child has developed internal coping resources or relies on screens for emotional regulation

- Every gift is a vote for which coping strategy your child develops—ask four questions before purchasing

- Children actually prefer play when offered meaningfully—the screen default is convenience culture, not kids’ choice

The 90% Problem

Over 90% of families report that screen time limits cause tantrums (much like gift-opening tantrums). If you’re nodding right now, you’re in the overwhelming majority. But here’s where it gets interesting: a 2024 study from Frontiers in Psychology tracking 654 preschoolers discovered something researchers didn’t expect.

The children who transitioned smoothly from screens? They weren’t the ones with better executive function skills. They weren’t the ones whose parents had mastered the “five-minute warning.”

They were the ones who could play—really play—with physical toys. (Do TikTok sensory toys count?).

Specifically, 37.1% of children who engage in sustained toy play experience no tantrums during screen transitions. The researchers put it plainly: “Play behavior with real toys is a stronger preventor of screen time tantrum than executive function skills.”

I’ve watched this play out with my own kids. My 4-year-old, who can disappear into block towers for 30 minutes, barely notices when screen time ends.

Her 6-year-old brother, who flits between activities and asks “what can I do?” every ten minutes, treats the iPad’s removal like a personal betrayal. Same house. Same parents. Same rules. Different play capacity.

Why Physical Play Changes Everything

The Moscow State researchers behind the 2024 study draw on Vygotsky’s theory that play serves as “an imaginary or illusory form of fulfillment of impossible wishes.” In plain terms: play is absolutely frustration-free because everything is possible within it.

When your daughter becomes a doctor in her pretend game, the emotions she experiences are real, and the tension she works through genuinely dissipates. She’s building internal resources for managing frustration—resources she can draw on when the screen goes dark.

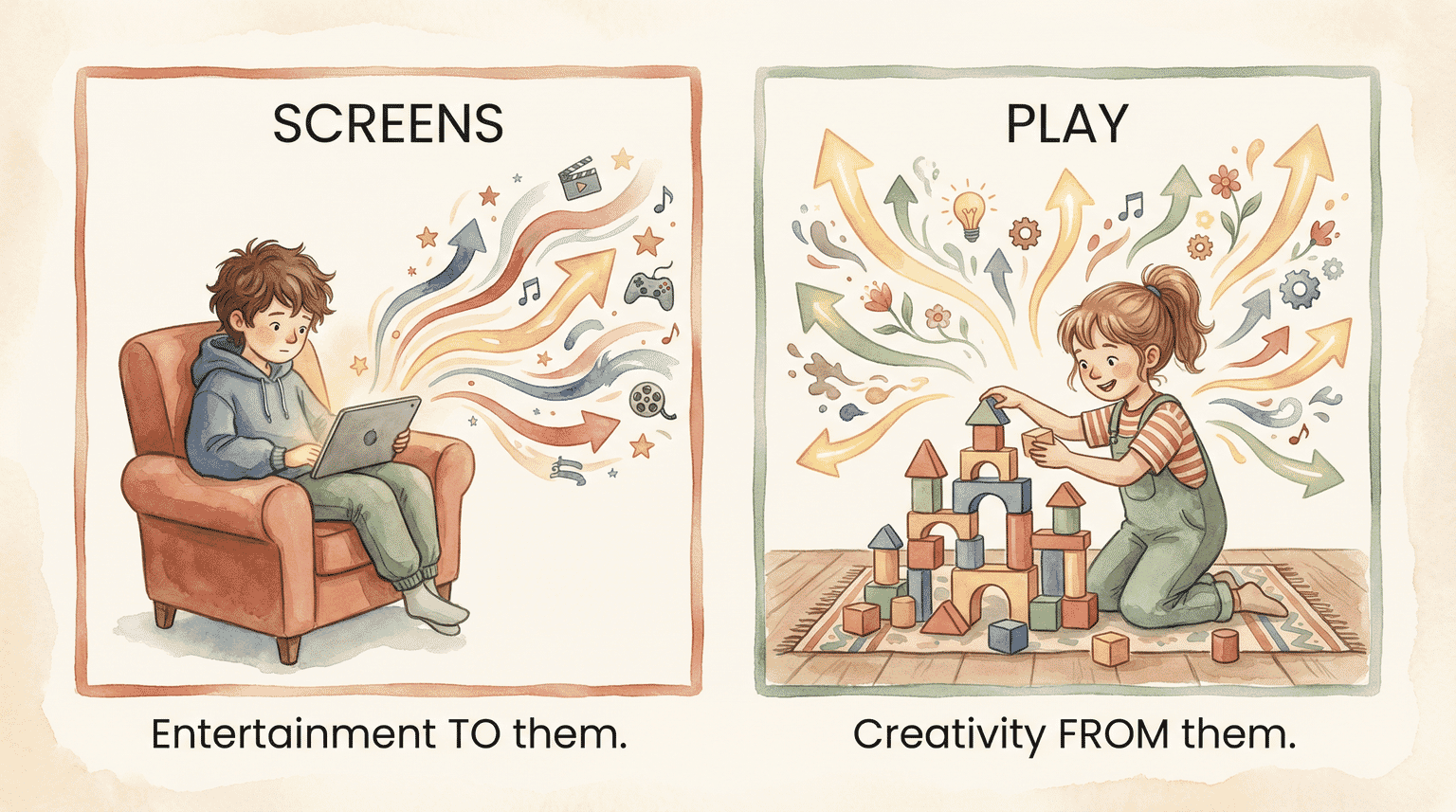

Here’s the mechanism: screens provide entertainment to children. Play requires something from them. That difference matters enormously for brain development.

A 2022 study on preschooler cognition found that children meeting the ≤1 hour/day guideline were 3.48 times more likely to have higher working memory.

The researchers explain why: “Extended screen time likely displaces developmentally appropriate activities. Since screen-based devices tend to provide impoverished stimulations compared to the real-time environment, such displacement may affect early brain development.”

This is the displacement effect—screens don’t just add to a child’s day, they subtract from it. Every hour on the iPad is an hour not spent developing why simple objects engage children longer than complex toys or building the frustration tolerance that comes from towers that fall down and puzzles that don’t quite fit.

The comparison couldn’t be clearer. One approach fills a child up from the outside. The other draws something out from the inside. And honestly? Only one builds the internal resources that last.

The Pacifier Trap

Here’s where well-meaning parents (myself included) get stuck. Your toddler is losing it in the grocery store. You hand over the phone. Peace descends. Problem solved, right?

Not according to a 2024 longitudinal study that followed 462 children from 12 to 36 months.

“When a child experiences negative affect due to having to give a toy back to a friend, offering to distract them with screen media may well reduce negative affect in that instant. However, it may hinder social interaction and prevent exploring alternative strategies for regulating the negative affect experienced.”

— Computers in Human Behavior, 2024 Longitudinal Study

In other words, screens as pacifiers prevent children from developing their own coping strategies. Worse, the research suggests children may learn to exhibit negative emotions instrumentally—crying specifically because they’ve learned it leads to screens.

I’ve seen this cycle in my own house. The difference between teaching delayed gratification through brief discomfort versus teaching kids that discomfort always gets fixed by a device is the difference between building regulation and building dependence.

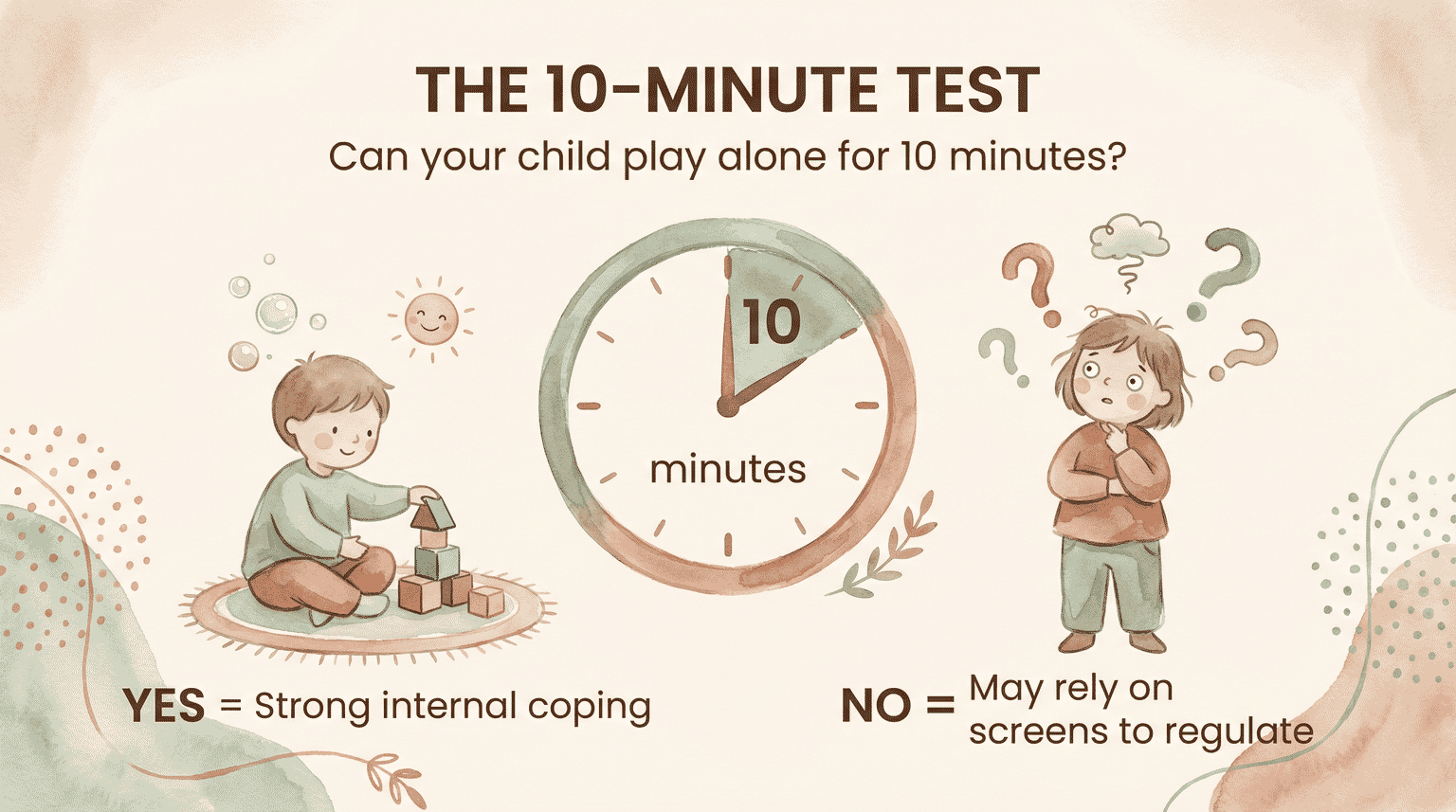

The research offers a sobering diagnostic question: Can your child play alone for 10 minutes? Children who can’t showed significantly more screen time tantrums (p < 0.001). That 10-minute threshold reveals whether children have developed internal resources for managing frustration—or whether they've learned to rely on external entertainment.

The Numbers We Need to Face

Let’s look at where families actually are. According to a 2025 University of Michigan poll, three in five children watch TV or videos daily. Nearly a third engage in video games. The majority of parents admit to handing over phones or tablets in the car, in public, or whenever they need their child occupied.

I’m not judging—I’ve done all of these things. With eight kids, survival mode is a permanent address, not a temporary stop.

But the research paints a concerning picture. A 2023 Canadian study found only 15% of children aged 3-4 meet screen time guidelines. Nine in ten U.S. children are introduced to devices before their first birthday.

As the researchers note: “The highest cost of too much screen time for young children is the loss of opportunities for social learning and practice.”

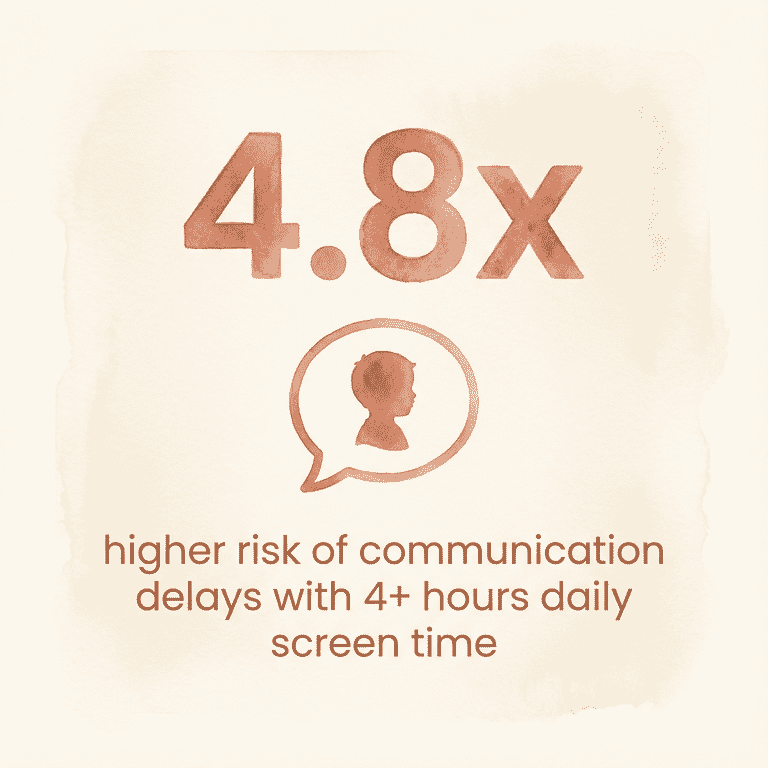

The stakes are real. A 2023 Japanese cohort study following 7,097 families found a dose-response relationship: children with 4+ hours of daily screen time at age 1 had 4.78 times higher risk of communication delays at age 2. The association persisted at age 4.

What parents can control, according to a systematic review of 53 studies: 17 of 20 studies found parental screen time predicts child screen time. A device in the bedroom strongly associates with higher usage.

Sedentary behavior, including screen time, tracks from early childhood into adulthood—meaning habits established now tend to stick.

When Screens Actually Work

Here’s where I deviate from the fear-based narrative. Not all screen time is created equal.

A 2025 APA review of 124 “educational” apps found most scored poorly on actual learning criteria. But—and this matters—psychological research has identified what makes media genuinely effective: meaningful interaction with characters, applicability to everyday experiences, and avoiding distracting effects and advertisements.

“If we use psychological science as a basis to create media products that capitalize on how human brains learn, we can develop better products and kids will get more out of it.”

— Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Temple University

The key distinction: interactive beats passive. Children who form “parasocial relationships” with characters—finding them trustworthy and friend-like—learn more effectively. Kids answer math problems faster when a character’s responses relate directly to their answers. AI-powered interactive characters show promising results for science learning.

“AI should always be considered a supplement to social interaction. Parents need to make sure that their children’s closest emotional relationships are with those who matter the most.”

— Dr. Sandra Calvert, Georgetown University

Let that sink in. The research isn’t anti-screen—it’s pro-connection. Screens become problematic when they replace human interaction, not when they supplement it.

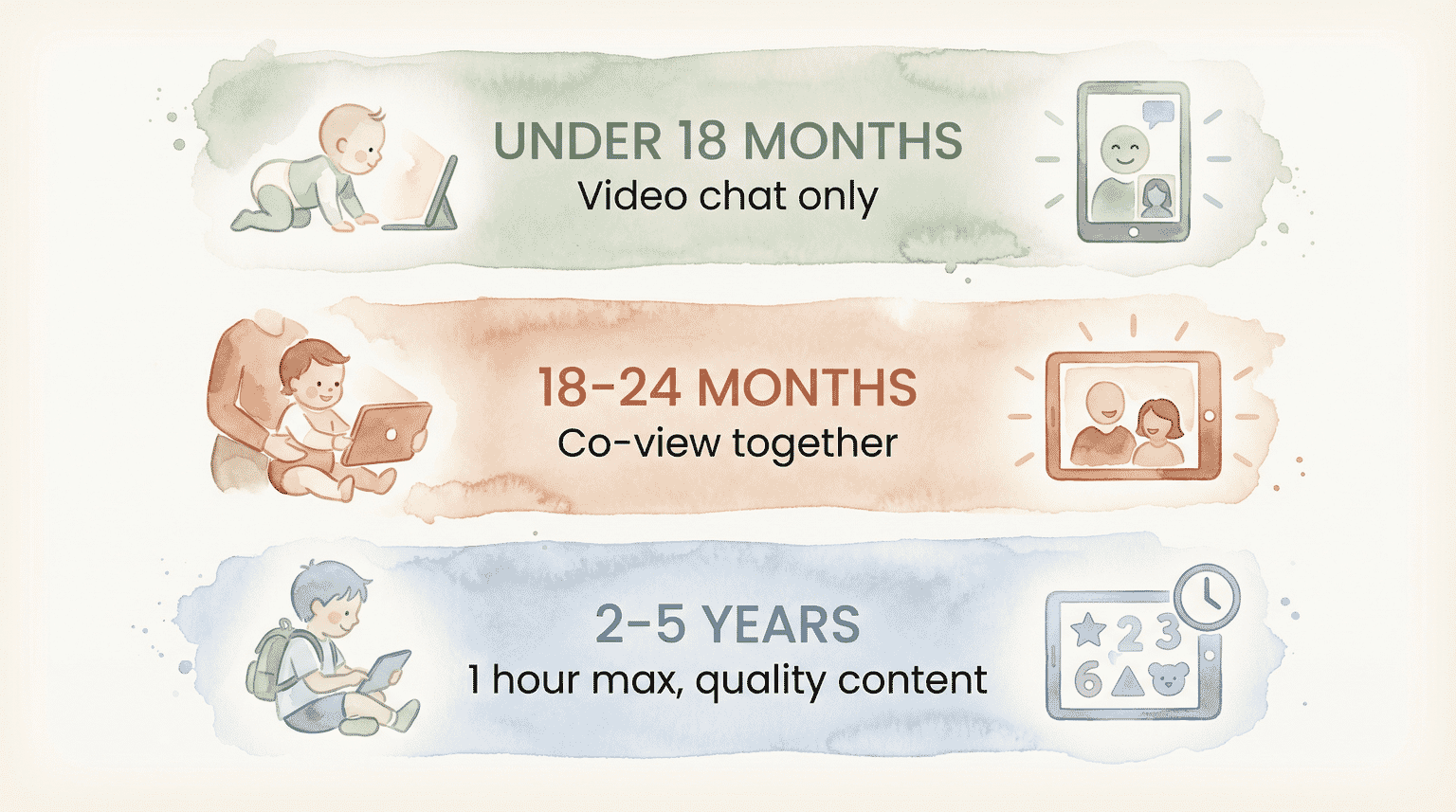

| Age | Recommendation | Reality Check |

|---|---|---|

| Under 18 months | Video chat only | 90% exposed to devices before age 1 |

| 18-24 months | High-quality content, co-viewed | Start slow, watch together |

| 2-5 years | ≤1 hour/day quality programming | Only 15% meet this guideline |

The gap between recommendations and reality is enormous. But rather than feeling guilty about the gap, focus on what the research actually shows matters: how screens are used, not just how much.

Dr. Thomas Robinson of Stanford is more direct: “For infants and young children, I recommend avoiding screens altogether. Young children benefit from more face-to-face time with their parents and other family members.”

The Gift Lens

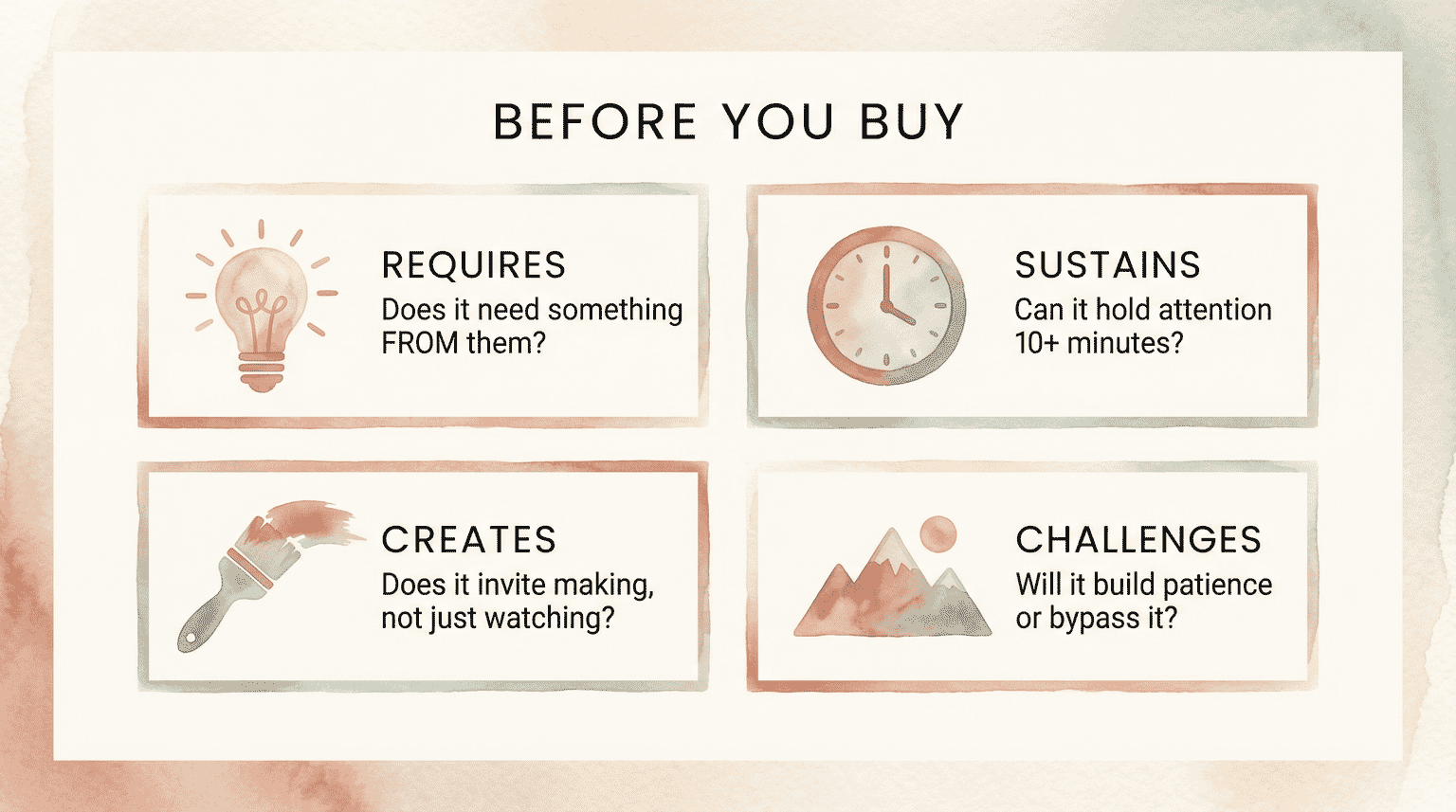

So what does this mean for the shift toward digital gifts and purchasing decisions?

Every gift is a vote for which coping strategy your child develops. A tablet loaded with games votes for external entertainment as regulation. Building blocks, pretend play sets, or open-ended toys vote for internal resources.

I’m not saying never buy screen-related gifts—we have gaming consoles and the kids use them. But I’ve started evaluating gifts through a play-capacity lens.

Questions I ask before purchasing:

- Does this require something FROM my child, or provide entertainment TO them?

- Could this sustain 10+ minutes of independent engagement?

- Does it invite creation, or just consumption?

- Will this build frustration tolerance or bypass it?

For the relatives conversation (or the screen time negotiation), I’ve found this framing helps: “We’re trying to build [child’s name]’s ability to play independently. Toys that don’t need batteries or wifi really help with that.” Most grandparents remember open-ended toys fondly—it’s an invitation, not a criticism.

“Play is the key to how young children learn and develop… risky play isn’t about recklessness but about appropriate challenges that allow young children to explore what they’re capable of.”

— Sarah Clark, MPH, Co-director, University of Michigan Mott Poll

Screens can’t offer that kind of challenge. Blocks can. Cardboard boxes definitely can.

The Path Forward

Here’s the preference paradox that surprised me most in the research: children actually prefer play when offered meaningfully. The Canadian study noted: “Given the choice, children will nearly always opt for talking, playing, or being read to over screen time in any form.”

The screen default isn’t a child’s choice—it’s convenience culture. Kids want connection and engagement. They settle for screens.

Start here: Can your child play alone for 10 minutes? If not, that’s your intervention point—not stricter screen limits, but building play capacity. Start with five minutes. Sit nearby but don’t direct the play. Let them struggle with boredom. Let them figure it out.

In my house, this looks like weathering complaints. “I’m bored” is not an emergency I need to solve. My job is to provide materials and space, then get out of the way.

The 2024 research reframes the entire screen debate: We’ve been focused on limiting screens when we should be focused on building alternatives. Children with strong play capacity don’t need strict limits—they naturally transition because they have somewhere engaging to go.

Every gift decision either builds that capacity or undermines it. Choose accordingly.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does my child have tantrums when screen time ends?

Research suggests children who cannot sustain independent play for 10 minutes show significantly more screen time tantrums. These children haven’t developed internal resources for managing frustration—they’ve learned to rely on screens as external emotional regulators. Building play capacity, not enforcing stricter limits, appears to be the actual solution.

Is screen time bad for toddlers?

Research shows a dose-response relationship: a 2023 study found that 4+ hours of daily screen time at age 1 was associated with nearly 5 times higher risk of communication delays. However, the greater concern may be displacement—what screens subtract from a child’s day in terms of social learning and play opportunities.

What should toddlers do instead of screen time?

Physical play develops both motor skills and frustration tolerance. Sustained play with physical toys—particularly play that children initiate and direct themselves—builds the emotional regulation capacity that actually makes screen transitions easier. The key is play that challenges without external entertainment.

How much screen time is OK by age?

The AAP recommends avoiding screens (except video chat) before 18 months, limited high-quality content with co-viewing at 18-24 months, and no more than 1 hour daily for ages 2-5. However, only 15% of preschoolers meet these guidelines. Focus less on strict minutes and more on whether children have developed alternative ways to manage boredom.

Do educational apps help children learn?

Most “educational” apps score poorly on actual learning criteria. The research distinction that matters: interactive content where children respond and receive feedback outperforms passive viewing. Even good apps should supplement, not replace, social interaction and physical play.

What About You?

How do you balance screen time with other activities at your house? I’d love to hear what’s worked for reducing the meltdowns when screens go off—and what alternatives have actually held your kid’s attention.

I read every reply and test the toy suggestions with my own crew.

References

- Frontiers in Psychology (2024) – Play behavior as prevention factor for screen time tantrums

- Computers in Human Behavior (2024) – Longitudinal study on screen time and emotional development

- JAMA Pediatrics (2023) – Japanese cohort study on screen time and developmental delays

- Paediatrics & Child Health (2023) – Canadian research on preschool screen time

- PMC (2022) – Screen time and cognitive development in preschoolers

- PMC (2023) – Systematic review of screen time correlates

- University of Michigan Mott Poll (2025) – National poll on children’s play habits

- American Psychological Association (2025) – Research on digital educational media effectiveness

Share Your Thoughts