Your five-year-old has never held the toy in their hands. They’ve never seen it in a store. But they can describe it in perfect detail—the exact colors, the sounds it makes, which accessories come inside. They know the brand name. They know they want it now.

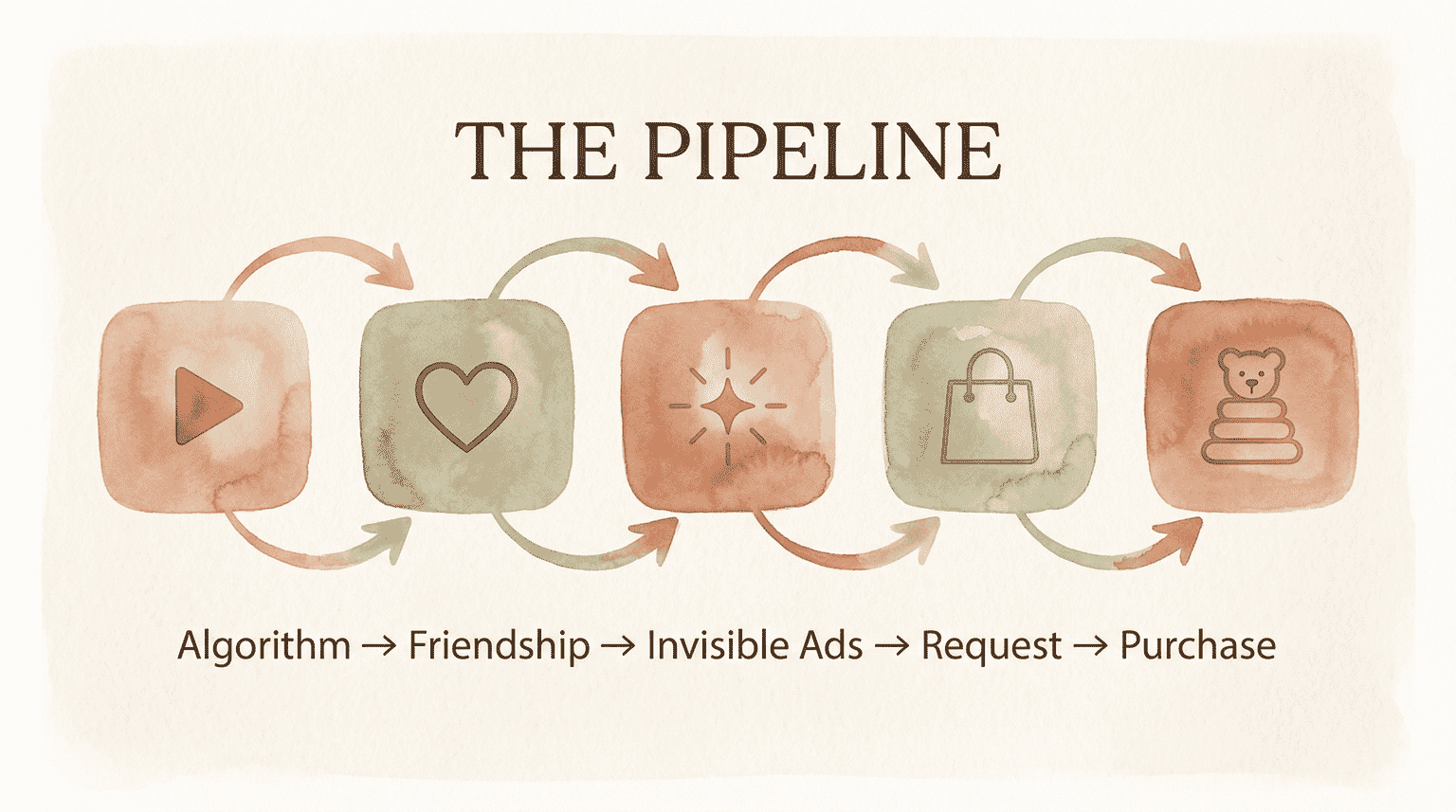

This is the pipeline at work. And once you understand how it operates, you’ll see it everywhere.

Key Takeaways

- Children form genuine one-sided friendships with YouTube influencers, making their product recommendations feel like advice from a trusted friend rather than advertising

- Kids under age 8 cannot distinguish embedded advertising from entertainment—they won’t fully understand persuasive intent until around age 12

- The marketing pipeline has five stages where parents can intervene: algorithm access, parasocial bonding, invisible persuasion, purchase requests, and retail encounters

- Co-viewing and simple questions like “I want to talk about what’s happening in this video” build media literacy over time

- Children who understand how the pipeline works become increasingly resistant to its effects

The Empire Before the Toy Aisle

Here’s a number that stopped me cold: Ryan Kaji earned $35 million in 2023. He’s thirteen years old. His 38 million YouTube subscribers—most of them preschoolers—have turned him into something more valuable than a celebrity. He’s become a brand. In 2024, he starred in his own feature film.

Ryan’s World merchandise generated over $250 million in 2020 alone, according to research from the University of Mary Washington. That’s not ad revenue from YouTube. That’s toys in Walmart. Clothing at Target. Toothbrushes, bedding, snacks.

My librarian brain couldn’t let this go. How does a kid opening toys on camera translate into that kind of commercial power? The answer isn’t luck or charm or even particularly good content.

It’s a carefully constructed pipeline—one that begins with an algorithm and ends in your living room.

Understanding this pipeline matters because it’s reshaping the broader shift in digital gift culture. The toys your children want, the gifts they expect, the way they think about stuff—it’s all being shaped by systems designed to create demand.

Stage One: The Algorithm Opens the Door

The pipeline starts with access. And access has never been easier.

Research from UNLV found that children as young as two can navigate YouTube to find the content they want. Two. Before they can read, before they understand what advertising even is, they’re swiping to their favorite creators.

One business executive described YouTube as “the most popular babysitter in the world.” Research from the University of Technology Sydney backs this up: 80% of children ages 8-12 use YouTube regularly, with 86% of teens on the platform.

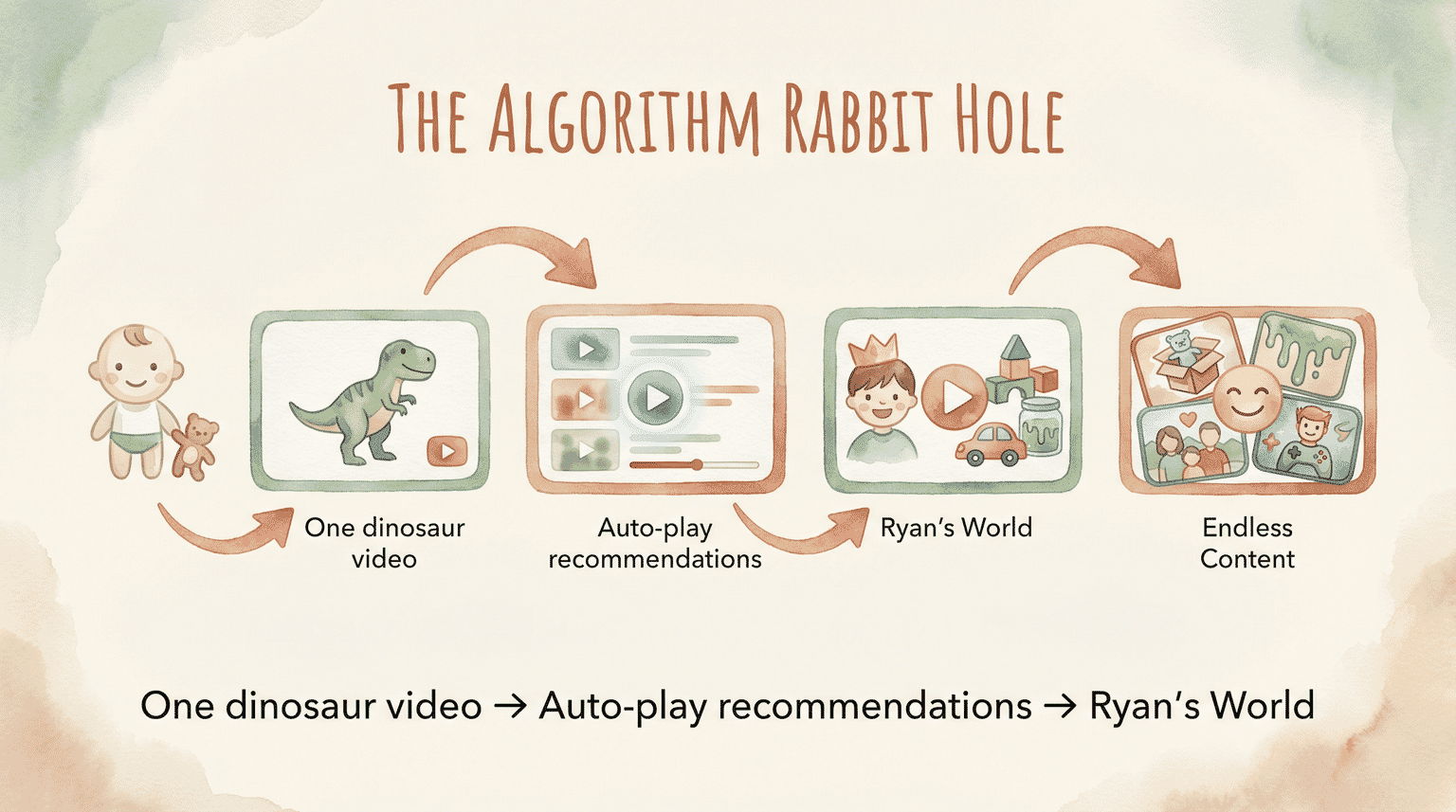

But here’s the part that makes the algorithm so effective—it doesn’t just wait for children to find content. A Pew Research study found that YouTube’s recommendation system consistently directs viewers toward children’s content regardless of their starting point. The algorithm is actively working to connect kids with creators like Ryan.

In my house, I’ve watched this happen in real time. My four-year-old started with one dinosaur video and within six “up next” auto-plays, she was deep in Ryan’s World territory. The door doesn’t just open—it pulls children through.

Stage Two: The Friendship That Isn’t

This is where things get psychologically interesting—and where most parents underestimate what’s happening.

Benjamin Burroughs, assistant professor of journalism and media studies at UNLV, studies what he calls parasocial relationships: the one-sided emotional connections viewers form with media figures. With Ryan, these connections are unusually powerful.

“There’s a feeling of proximity, of closeness to Ryan, who’s just like a regular kid with a regular family. It produces this kind of proximity to the audience.”

— Benjamin Burroughs, Assistant Professor, UNLV

My eight-year-old once referred to Ryan as “my friend Ryan.” She’s never met him. She never will. But after hundreds of hours of content, her brain has built a relationship model that feels like friendship.

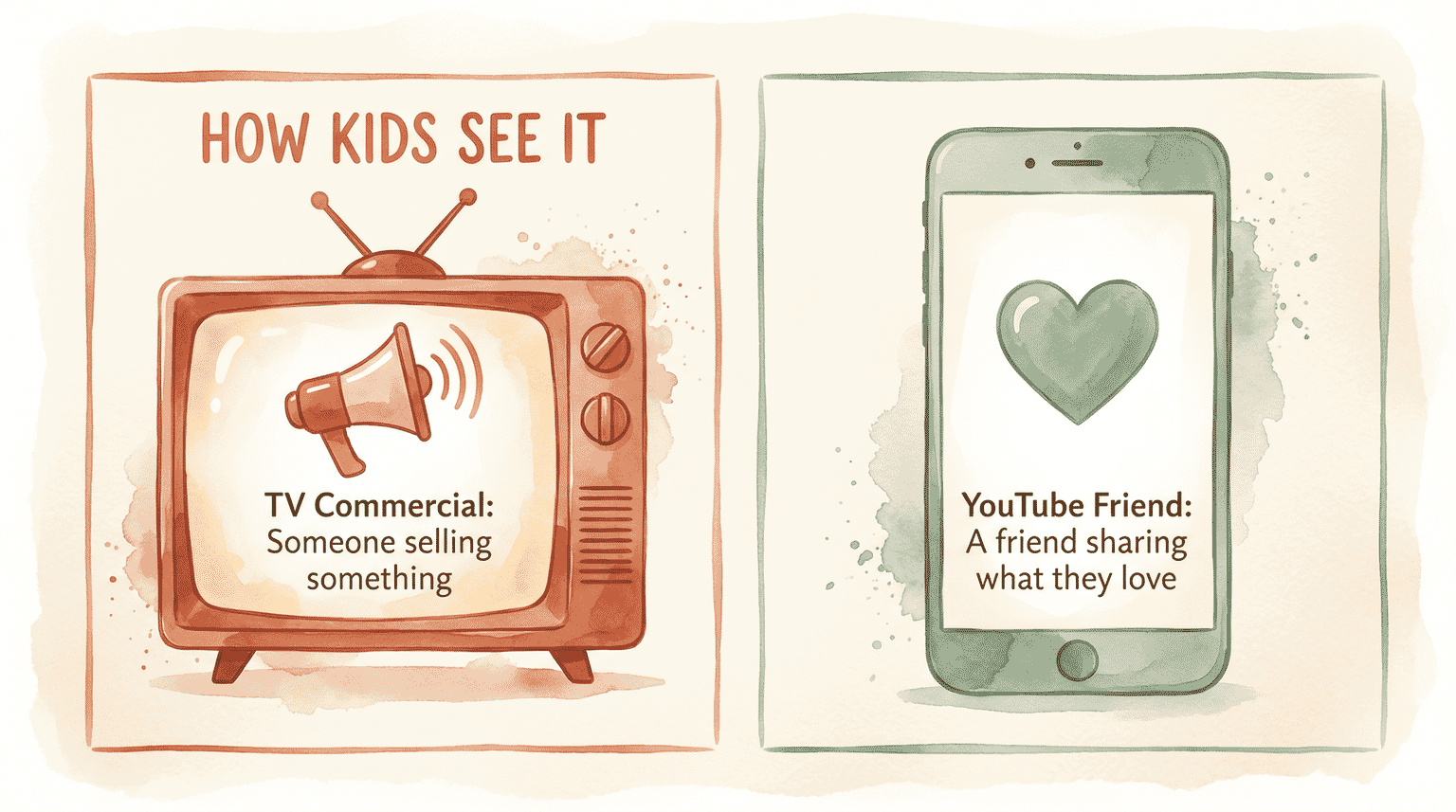

This is fundamentally different from how children experience traditional advertising. A commercial features actors playing roles. Ryan is Ryan—eating breakfast, playing games, interacting with his parents. To understand why unboxing videos captivate children so intensely, you have to understand this: children aren’t watching a show. They’re hanging out with a friend.

And when a friend recommends something, it doesn’t feel like being sold to.

Stage Three: The Invisible Persuasion

Here’s the developmental reality most parents don’t know: children under age eight believe commercials exist to help them make good purchasing decisions. They genuinely think ads are informative rather than persuasive.

Full comprehension of advertising’s persuasive intent doesn’t develop until around age twelve. Understanding the developmental science behind how children process gifts helps explain why this matters so much.

This matters enormously because embedded advertising—products woven seamlessly into entertaining content—is dramatically harder for children to identify than traditional commercials.

Foundational research on children’s advertising comprehension shows kids demonstrate significantly more sophisticated understanding of TV ads compared to influencer content.

The University of Mary Washington study documents how Ryan’s World videos employ sophisticated marketing techniques: products used as challenge prizes, family members wearing branded merchandise, special effects making toys appear more exciting. Adults understand these sparkles and sound effects are added in post-production. Children under eight cannot make this distinction.

A complaint from Truth in Advertising put it starkly: “Organic content, sponsored content—it’s all the same to preschoolers.”

So when regulators require disclosure—those tiny “paid partnership” labels—they’re implementing a solution designed for adult cognition. Preschoolers can’t read the disclosure, wouldn’t understand the word “ad,” and likely wouldn’t notice a disclaimer anyway. The persuasion operates invisibly, exactly as designed.

Stage Four: The Request Materializes

You’ve seen this stage. It usually happens in Target.

BYU research documented what they call “pester power”—children’s influence over family purchasing that develops directly from watching unboxing content. After viewing, children don’t just want “a toy.” They know exact brand names to seek when entering stores.

I’ve experienced this with six of my eight kids now. The specificity is remarkable. Not “a slime kit”—that slime kit, the one with the purple container, the one Ryan opened in the video from three weeks ago.

The content creates demand for particular products rather than general category interest. This is why brands pay influencers so much—research from the Michigan Journal of Law Reform documents rates of $10,000-$15,000 for a promotional Instagram post and approximately $45,000 for a sponsored YouTube video. These payments only make sense if the influence actually works.

And it does. By the time your child is standing in the toy aisle, pointing at specific packaging, the pipeline has already done most of its work.

Stage Five: Retail Partnerships Complete the Loop

The final stage is perhaps the most impressive piece of engineering. Ryan didn’t stay on YouTube. Through a company called Pocket Watch—founded by former Nickelodeon and Disney executives—he transformed from content creator to global brand.

Ryan’s World products now exist at virtually every price point: dollar store items for impulse purchases, mid-range toys for birthday gifts, premium items for Christmas lists. This isn’t accidental. It’s strategic distribution designed to capture demand wherever it emerges.

Burroughs observed this transformation directly: “As a child influencer, he’s being courted by companies to play with the latest toy so that other children can see it. But now, the child influencer himself has become a brand.”

The pipeline now feeds itself. Content creates product demand. Products create more content opportunities. Children watching want to be like Ryan—and being like Ryan means constant consumption.

“There is kind of a pernicious promise of YouTube that’s all about consumption. And connecting consumption and play in a way that creates this need for constant consumption.”

— Benjamin Burroughs, Assistant Professor, UNLV

My own kids have asked to do the activities shown in Ryan’s family videos. They expect our family to mirror what they see—not understanding that “regular family” content is professionally produced commercial entertainment.

The Intervention Map

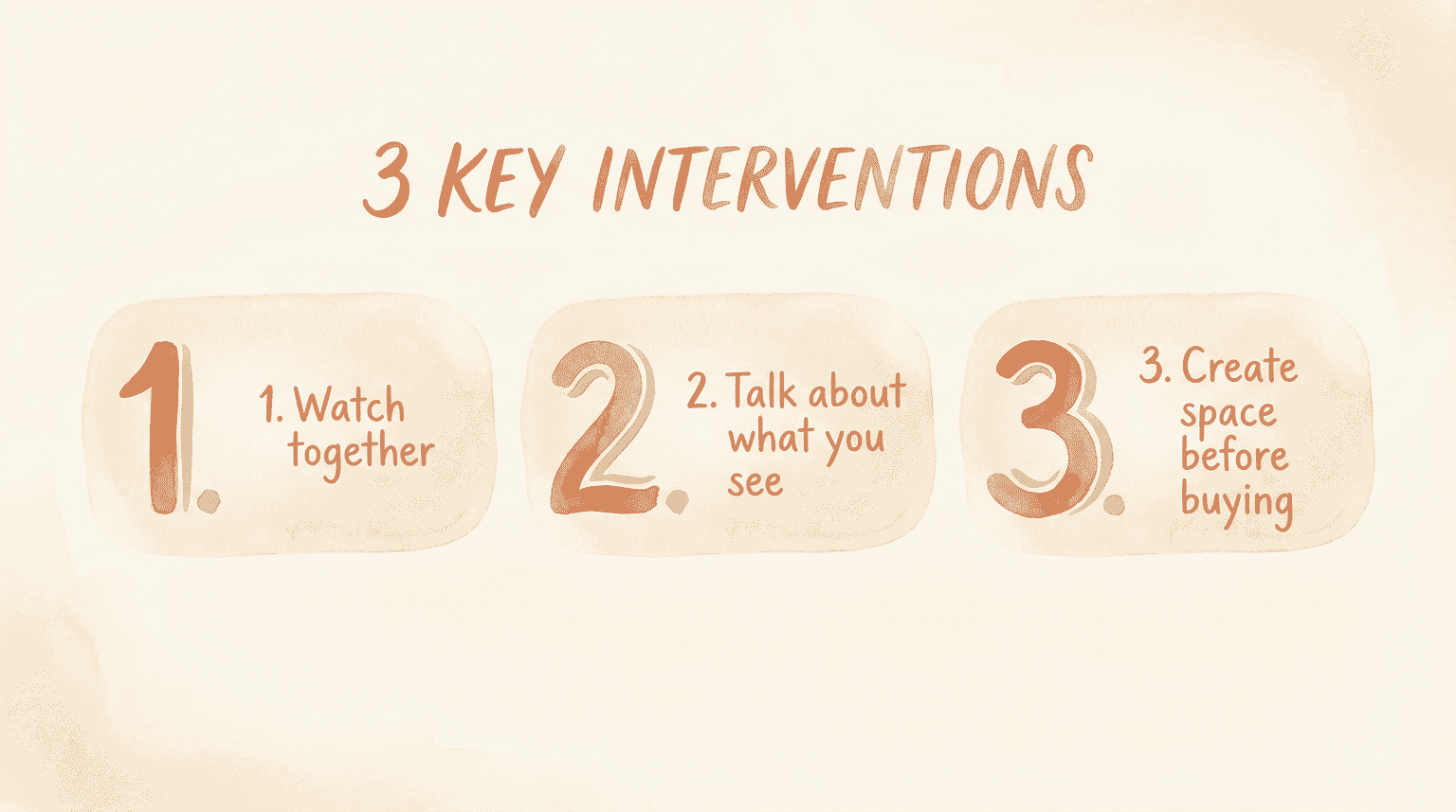

Here’s the good news: understanding the pipeline means understanding where you can intervene. You don’t have to stop the entire machine—you just need to introduce friction at key points.

Stage One intervention (Algorithm access): Consider platform alternatives with less aggressive recommendation systems. YouTube Kids offers some filtering, though it’s imperfect. Downloading specific approved content eliminates algorithmic rabbit holes entirely.

Stage Two intervention (Parasocial formation): Co-viewing disrupts the illusion of private friendship. When you watch together and comment on what you see, you insert yourself into the relationship. Research suggests active parental presence changes how children process influencer content.

Stage Three intervention (Invisible persuasion): Age-appropriate conversations about advertising begin earlier than you’d think. Even preschoolers can start understanding “Ryan gets toys to show us so we’ll want them too.”

Stage Four intervention (Request response): Validate the feeling without promising the purchase. “I can see you really want that. Let’s put it on your birthday list” acknowledges desire while creating space between exposure and acquisition.

Stage Five intervention (Retail navigation): Preview store trips. “We’re getting birthday supplies, not toys today” establishes expectations before the pipeline’s physical endpoint appears.

For more comprehensive strategies for managing toy-focused YouTube content, the key is consistency across all five stages.

What Parents Can Actually Say

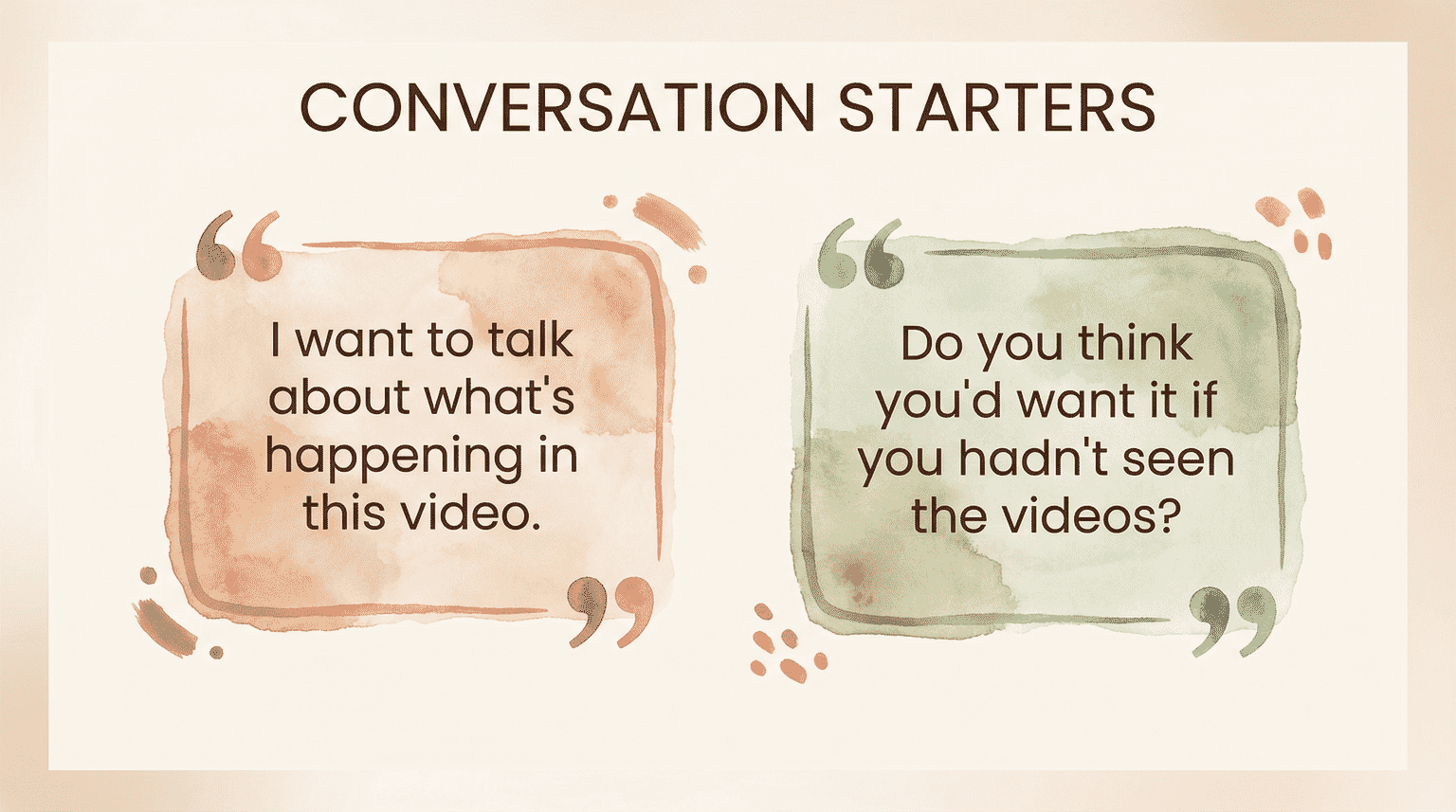

Jason Freeman, professor at BYU’s School of Communications, emphasizes that advertising literacy develops over time, not in single conversations. His research offers one particularly useful phrase:

“I want to talk about what is happening in this video.”

— Jason Freeman, Professor, BYU School of Communications

This opens dialogue without accusation or prohibition. From there, try these conversation starters:

During unboxing viewing:

“Did you notice how excited Ryan acted about that toy? I wonder if it’s really that exciting, or if he’s showing it that way so more people want to buy it.”

At store encounters:

“You’ve seen this on Ryan’s channel, right? That’s interesting—they made a toy to look just like what he plays with. Do you think you’d want it if you hadn’t seen his videos?”

For gift occasions:

“I know you love watching Ryan, and some of his toys look fun. Let’s think about which ones you’d actually play with a lot, not just which ones looked cool in the video.”

The goal isn’t to make children feel stupid for wanting things. It’s building the critical thinking skills that developmental research says won’t fully emerge until age twelve.

The Long Game

Here’s what I’ve found encouraging after watching eight kids navigate this landscape: media literacy can be taught. The URI research found that media literacy education had a statistically significant positive effect on children’s wellbeing.

Your child’s interest in Ryan’s World can actually become a teaching opportunity. That fascination with unboxing videos? It’s a doorway to conversations about persuasion, about the difference between wanting and needing, about how businesses work.

My twelve-year-old—who once wanted everything Ryan touched—now watches influencer content with a producer’s eye. “That’s definitely sponsored,” she’ll say, pointing out the careful product placement. She taught herself to see it, with years of our conversations as foundation.

The pipeline won’t disappear. But children who understand how it works become increasingly resistant to its effects. That’s not cynicism—it’s literacy.

And that’s something you can actually give them.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does my child love Ryan’s World so much?

Children develop parasocial relationships through regular viewing—they genuinely feel like Ryan is their friend. This perceived closeness makes his toy recommendations feel like suggestions from someone they trust rather than advertisements.

Is Ryan’s World appropriate for kids?

The content is designed for children under five, but developmental research shows preschoolers cannot distinguish advertising from entertainment. If your child watches, consider active co-viewing and age-appropriate conversations about what they’re seeing.

How do I talk to my child about Ryan’s World?

Start by watching together and saying, “I want to talk about what’s happening in this video.” Help children recognize when Ryan is showing them something to buy, without making them feel foolish for wanting it.

Are unboxing videos harmful to children?

Research shows embedded advertising bypasses children’s developing cognitive defenses more effectively than traditional commercials. The greater concern isn’t any single video but the cumulative effect of constant exposure on children’s relationship with consumption.

I’m Curious

How has YouTube changed what your kid asks for? I’ve watched my children go from “I want a toy” to wanting specific toys they’ve never seen in person. Would love to hear if you’ve noticed the same pipeline at work.

I read every comment and learn so much from your experiences.

References

- University of Mary Washington (2025) – Content analysis of advertising techniques in Ryan’s World videos

- UNLV (2020) – Research on parasocial relationships and child influencer impact

- BYU School of Communications (2022) – Parent detection of commercial content in unboxing videos

- El País (2024) – Expert psychological perspectives on kidfluencer industry

- University of Technology Sydney (2022) – Platform usage statistics and toy market analysis

- Michigan Journal of Law Reform (2023) – Financial mechanics of kidfluencer marketing

Share Your Thoughts