Your child checks the Amazon tracking page for the third time in an hour. The package was ordered yesterday. Before that, they asked about this specific toy every single day for two weeks—ever since they saw it in a YouTube video that wasn’t even supposed to be an advertisement.

Sound familiar? Welcome to digital pester power, and I’m here to tell you: this isn’t your imagination. What you’re dealing with really is different from what your parents faced.

My librarian brain couldn’t let this go without digging into the research. With eight kids spanning ages 2 to 17, I’m watching digital pester power play out across every developmental stage simultaneously—and the science behind why it feels so relentless actually helped me respond more effectively. Here’s what I found.

Key Takeaways

- Digital pester power is more intense because algorithms create endless repetition loops that traditional TV ads never could

- Children under 12 literally cannot distinguish advertising from entertainment—their brains aren’t developmentally ready

- Viewing desirable products triggers actual hunger hormones, creating physical wanting that logic can’t easily override

- The “delay technique” works because 70% of algorithm-driven requests don’t survive a one-week waiting period

- Limiting screen time to under 2 hours directly reduces product desire by 25-27%

What Makes Digital Pester Power Different

Digital pester power describes children’s persistent product requests triggered by online content—including targeted ads, influencer promotions, and algorithm-driven recommendations. Unlike traditional TV advertising, digital pester power operates continuously through personalized content feeds, making exposure harder for parents to monitor and children’s requests more frequent and intense.

Here’s the baseline we’re working with: a 2020 PMC study found that 80% of parents whose children regularly accompany them to supermarkets admitted to spending more when children were present. That’s not new—kids have always influenced family purchases.

What’s new is the ammunition.

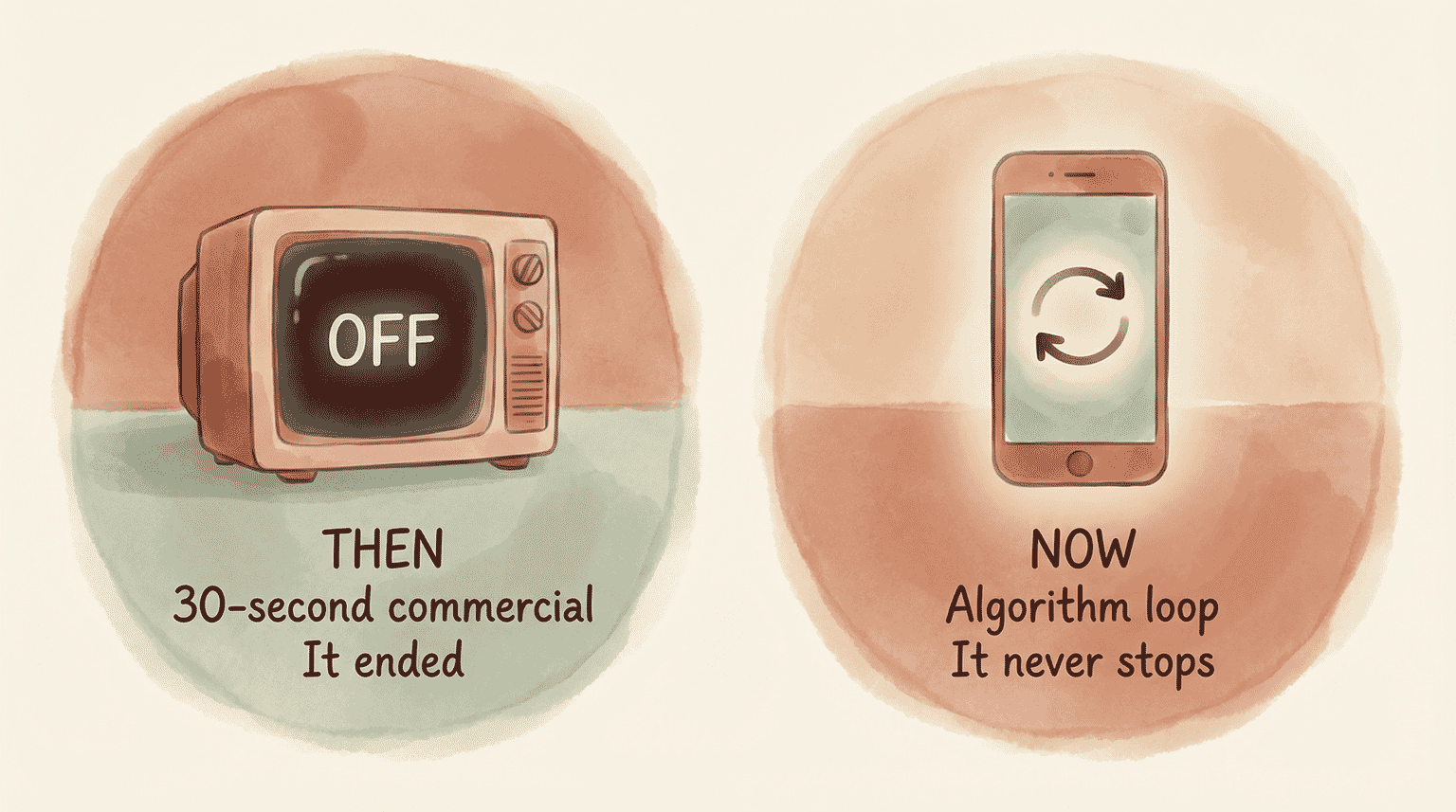

Your parents dealt with 30-second TV commercials that ended. You’re dealing with algorithmic persuasion that follows your child from device to device, session to session, creating repetition loops specifically designed to build desire.

The commercials your parents could mute or walk away from have evolved into content that doesn’t announce itself as marketing at all.

The Algorithm-to-Nagging Pipeline

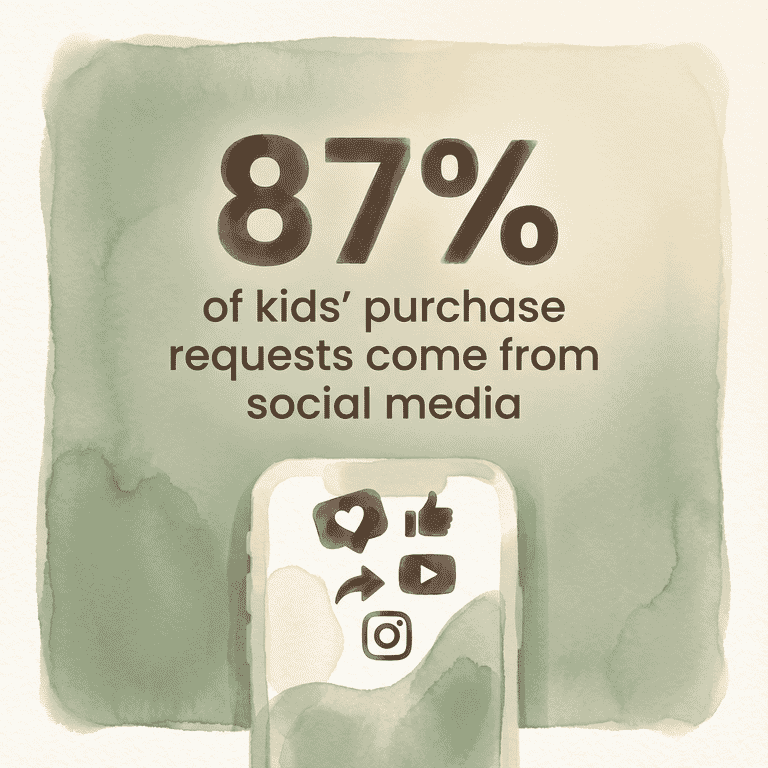

Research published in 2023 found that 87% of parents say their children influence purchase decisions, with requests primarily triggered by social media: Snapchat, TikTok, YouTube, Instagram. These platforms have become what researchers call “new socialization agents” for children.

Here’s the mechanism that makes this so persistent: recommendation algorithms are designed to show your child more of what they’ve already engaged with. If your 8-year-old watches one video about a particular toy, the algorithm doesn’t file that away—it serves up similar content repeatedly. The commercial that once aired and ended now loops indefinitely.

In my house, this looks like my 10-year-old suddenly wanting a very specific brand of slime kit. Not slime in general—that slime kit, from that channel.

I traced it back to a single video that had led to seventeen more “recommended” videos, all featuring the same product. The algorithm had created a repetition loop more effective than any advertising campaign from my childhood.

A 2021 study put numbers to this pattern: marketing influence (including packaging and advertising) strongly predicts nagging behavior, with a correlation strong enough to explain 47% of the variance in how often children pester. The pipeline from exposure to request is direct and measurable.

Understanding this mechanism helped me stop taking the requests personally. My kids aren’t greedier than I was—they’re just facing a more sophisticated system.

Why Children Can’t See What’s Happening

Here’s what changed my perspective entirely: children aren’t choosing to be susceptible to this. Their brains literally cannot process what’s happening.

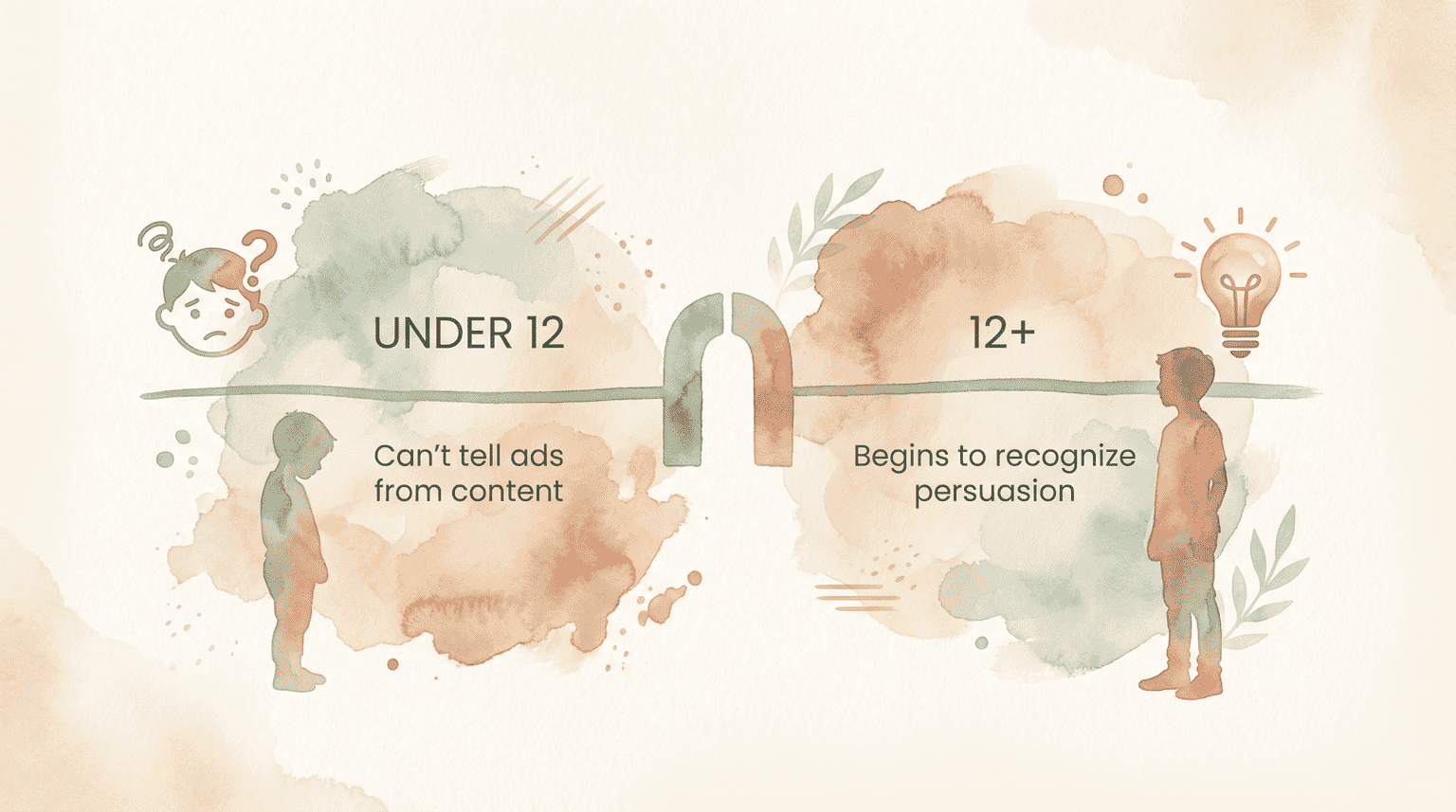

Research on digital media and child development identifies age 12 as the threshold when children begin reliably distinguishing advertisements from other media content. Before that age, children’s brains lack the cognitive development to understand that the enthusiastic person unboxing toys has persuasive intent.

The neuroscience of children’s media consumption reveals something that should shape how we respond to these requests.

“Young children cannot be expected to critically understand the commercial messages or persuasive motivations of advertisers or influencers.”

— Jenny Radesky, MD, Developmental Behavioral Pediatrician, University of Michigan

Her analysis of over 1,600 videos viewed by children ages 0-8 found frequent branded content, with “high-pleasure” unboxing videos engaging young viewers through reward mechanisms. On some channels, the duration of advertisements exceeded the duration of the actual video content. Children watching what they think is entertainment are actually watching extended commercials.

This is why a 2024 study noted that “it is seemingly more difficult for consumers, particularly children, to distinguish between advertising and entertainment in a digital setting.” The blurred lines aren’t accidental—they’re the entire strategy.

My 6-year-old once told me a YouTube creator was “her friend” who “really likes” a particular toy. That’s not naivety—that’s exactly the mimetic desire dynamic researchers have documented, where children model their wants on people they perceive as similar or admirable.

The Biological Want Response

This is the finding that genuinely surprised me: digital pester power creates actual physical wanting, not just psychological desire.

The same European study of over 7,000 children found that viewing images of desirable products triggers ghrelin secretion—the same appetite hormone that creates physical hunger sensations. When your child says “I really want it,” they may be describing something happening in their body, not just their imagination.

Children in this study averaged 2.4 hours of daily screen time, with 54.8% exceeding recommended guidelines. The research found that increasing digital media exposure was associated with higher preferences for marketed products.

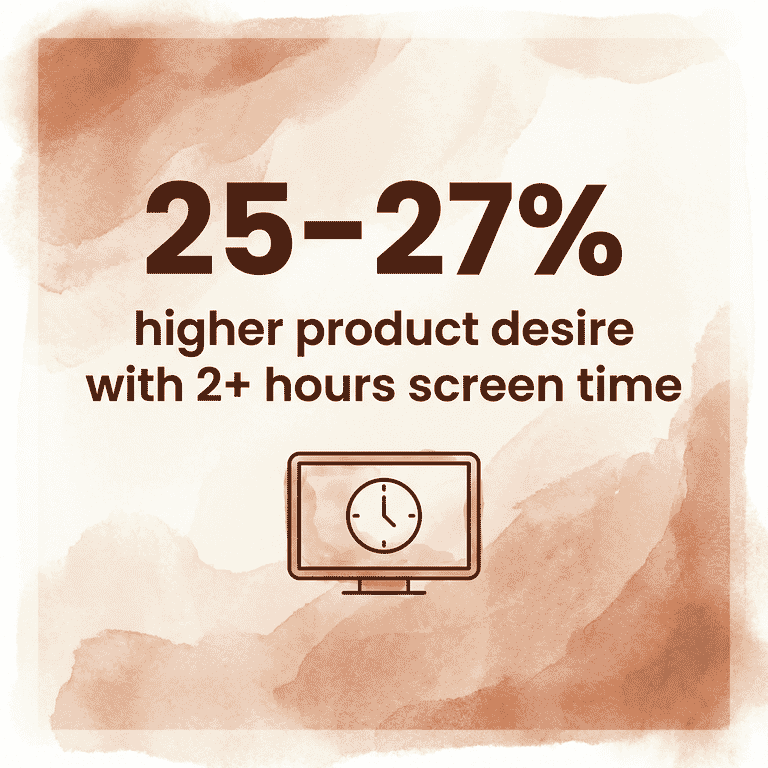

Children exceeding 2 hours daily showed 25-27% higher odds of wanting what they’d seen advertised.

This mechanism explains why digital requests feel so urgent to children—and why simply saying “you don’t need that” rarely works. The desire they’re experiencing has a biological component that logic can’t easily override.

I’ve watched this with my own kids. The intensity of wanting something they’ve seen repeatedly on a screen is different from wanting something they spotted once in a store. The algorithm-created repetition combined with physiological response creates a sense of urgency that’s genuinely distressing to them.

The Parent Blind Spot

If you feel caught off-guard by how effective digital marketing is on your kids, you’re not alone—and there’s research explaining why.

A 2022 study found that while 56% of parents were aware of television advertising to children, only 25% recognized that unhealthy products were being advertised online. We’re trained to recognize traditional commercials. We’re not trained to recognize that the 12-minute “surprise egg” video is a 12-minute advertisement.

Parents in that study described feeling “bombarded by manipulative marketing”—but many only recognized it after researchers showed them specific examples of digital advertising. After seeing these examples, 67% of parents said it changed their views on what their children were actually being exposed to.

There’s also a psychological phenomenon researchers call the “third-person effect”: parents consistently believe other children are more influenced by marketing than their own children. In one UK study, all 42 parents agreed that over 40% of children would want unhealthy foods after exposure to online advertising, yet most believed their own children would not be affected.

We underestimate what’s happening because digital marketing doesn’t look like marketing, and because we instinctively believe our kids are the exception.

Resistance Strategies That Actually Work

Understanding the mechanism makes response strategies more effective—you’re no longer fighting blind.

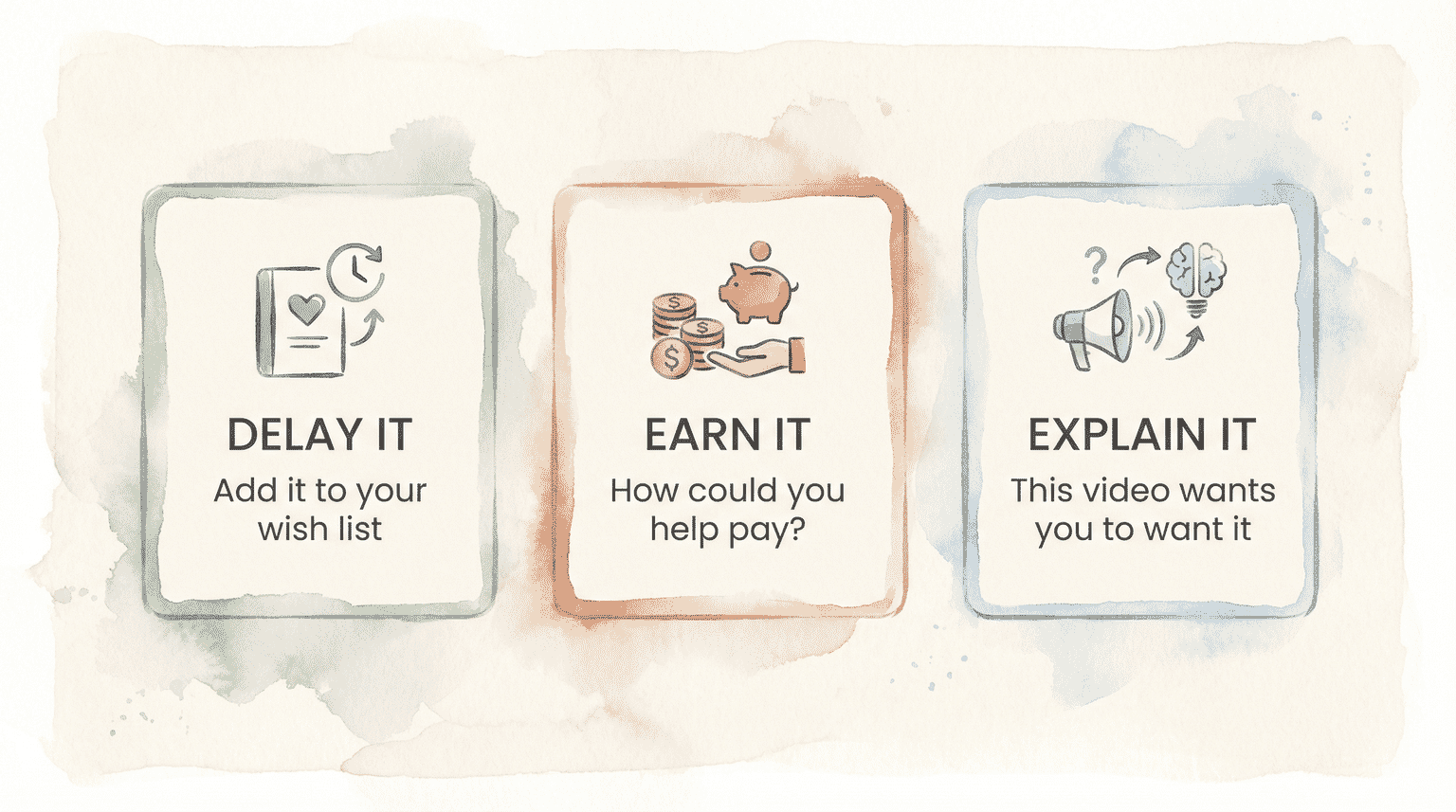

The 2023 research on co-shopping and e-commerce identified three parent strategies that work:

Promising (The Delay Technique)

“Let’s add that to your wish list and we can look at it together next week.”

One parent in the study explained: “If you really, really want that in a week from now, I’ll consider it then, and then it usually goes away.” The delay interrupts the algorithm-created urgency. In my experience, about 70% of requests don’t survive a one-week waiting period. (See our four phrases that actually work for specific language.)

Negotiating (Conditions and Trade-offs)

“If you want that, let’s figure out how you could earn part of it through chores—or what you’d be willing to give away to make room for it.”

This strategy works because it shifts from impulse to planning, engaging a different part of the brain than the immediate-wanting response.

Educating (Age-Appropriate Media Literacy)

“This video wants you to want that toy—that’s its job. The person making it gets paid when you ask me for things.”

For children under 12, keep explanations simple and non-judgmental. For older kids, more sophisticated discussions about targeting, algorithms, and sponsorships become appropriate.

Consistency Matters Most

Research on operant conditioning shows that intermittent reinforcement makes behavior hardest to extinguish. If you sometimes give in after persistent nagging and sometimes don’t, you’re functioning like a slot machine—and slot machines are specifically designed to keep people trying.

Consistent responses work faster than inconsistent ones, even when the consistent response isn’t the one they want.

Prevention Over Reaction

The research points toward proactive strategies rather than reactive battles:

Pre-screen agreements about purchase conversations reduce in-the-moment conflict. Before the tablet comes out: “Remember, watching doesn’t mean asking.”

Screen time limits directly reduce pester power. The European study found children exceeding 2 hours daily screen time had significantly higher preferences for marketed products.

Thoughtful gift decisions can short-circuit the desire-to-demand cycle entirely. When children know gifts come from intentional family processes rather than nagging, the equation changes.

Understanding this mechanism won’t eliminate pester power—it’s been around since children could point and say “want.” But knowing why digital pester power feels harder gives you better tools for responding. You’re not failing at something your parents succeeded at. You’re managing a system specifically designed by professional marketers to create desire in developing brains.

For more strategies on managing the emotional complexity of gift-related requests, our guide to common gift-giving challenges covers scenarios from grandparent conflicts to holiday overwhelm.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is digital pester power worse than TV advertising?

Digital pester power is more persistent because algorithms create personalized repetition loops. Unlike TV commercials that aired and ended, recommended content follows children across devices and sessions. A 2023 study found 87% of children’s purchase requests now come from social platforms where advertising is embedded within entertainment children cannot distinguish from genuine content.

At what age can children recognize online advertising?

Research identifies age 12 as the threshold when children begin reliably distinguishing advertisements from other media content. Before this age, children’s brains lack the cognitive development to understand that influencers and unboxing videos have persuasive intent. Simple media literacy conversations can begin earlier, but full comprehension of persuasive tactics comes later.

Does limiting screen time reduce pester power?

Yes, directly. A large European study found children exceeding 2 hours daily screen time had 25-27% higher odds of preferring marketed products. Limiting exposure reduces both algorithm-driven repetition and the biological wanting response triggered by viewing desirable images repeatedly.

Should I feel guilty for giving in to pester power?

Research suggests approximately 80% of parents resist most nagging. When children’s requests stem from biological wanting responses and cognitive inability to recognize advertising, occasional accommodation isn’t “giving in”—it’s navigating a system designed by professional marketers. Focus on establishing consistent patterns rather than perfection.

Share Your Story

How do you handle pester power in the digital age? I’d love to hear what’s worked for managing the constant “I saw it online and I need it” requests—especially strategies that don’t require saying no 500 times a day.

Tell me your best digital pester power survival tactics in the comments below.

References

- Parents’ Perceptions of Children’s Exposure to Unhealthy Food Marketing (2022) – Research on parental awareness gaps between traditional and digital marketing

- Pester Power: Examining Children’s Influence (2020) – Foundational study on children’s influence on family purchasing

- Digital Media Use and Sensory Preferences (2021) – European study on screen time and wanting responses

- Co-shopping and E-commerce Strategies (2023) – Research on parent strategies for managing digital purchase influence

- Digital Wellbeing in Early Childhood (2024) – MIT Press research by Jenny Radesky on children’s digital media exposure

- How Powerful is Pester Power? (2021) – Mixed-method study on marketing-to-nagging correlation

- Advertising Exposure and Household Purchases (2024) – UK study on advertising effects on family purchasing behavior

Share Your Thoughts