Your teenager just walked past your home office and paused. “Is that… the Millennium Falcon Lego set? The big one?” You look up from the instruction booklet—step 47 of 1,087—and feel a flicker of something. Guilt? Defensiveness? Or maybe just annoyance at being interrupted mid-build.

Here’s what the research actually shows: you’re not alone. Not even close.

Key Takeaways

- 43% of U.S. adults bought a toy for themselves last year—you’re in good company

- Research shows nostalgia-driven play actually helps adults cope with stress and maintain emotional balance

- The key distinction: healthy collecting recharges you for adult responsibilities rather than replacing them

- Shared toy interests can create “horizontal parenting” moments where you connect as equals with your kids

The $28 Billion Secret in Your Closet

A 2024 Circana survey found that 43% of U.S. adults bought a toy for themselves in the last year. More striking still: from January to April 2024, adults bought more toys than any other age group—surpassing preschoolers for the first time in history.

The term “kidult” isn’t new. TV executives coined it in the 1950s for adults watching children’s programming. But the phenomenon has exploded. Kidult shoppers helped U.S. toy sales surge 37% between 2020 and 2022, reaching $28.6 billion. Today, adults over 12 consistently outspend traditional under-12 demographics.

What is a kidult? A kidult is an adult who purchases toys, games, and collectibles for personal enjoyment rather than for children. The term emerged in the 1950s when TV executives used it for adults watching children’s programming.

Today, kidults represent 18% of U.S. toy sales, with 43% of American adults reporting they bought a toy for themselves in the last year.

So if you’ve got a growing Squishmallow collection hidden in your closet or a dedicated shelf for Funko Pops, welcome to a very crowded club. The real question isn’t whether this is normal—the data says it is. The question is: what does it mean for your family?

The Psychology Behind the Purchase

My librarian brain couldn’t let this go without checking the research. Why do so many adults feel drawn to toys they haven’t touched in decades?

“When people experience stress, anxiety, sadness, loneliness or other unpleasant mental states, nostalgic reflection helps them see a bigger picture… I am increasingly seeing positive aspects of it.”

— Dr. Clay Routledge, Vice President of Research, Archbridge Institute’s Human Flourishing Lab

Nostalgia, it turns out, isn’t about being stuck in the past. A foundational study on nostalgia found it actually connects one’s past and present selves, fostering what psychologists call “self-continuity.” When you pick up that Hot Wheels car identical to one you had at age seven, your brain isn’t regressing—it’s integrating.

The pandemic accelerated everything. During lockdowns, 58% of adult respondents in a Toy Association survey acquired toys for personal use. When restaurants closed and concerts vanished, adults turned to the comforts they could access. And they kept buying even after restrictions lifted.

A BBC survey found that 47% of adults who bought toys for themselves say they’re “fun and good for their mental health.” Even more compelling: 9 in 10 adults said playing with Lego offered them relief from worries and allowed them to destress.

This isn’t Peter Pan syndrome. It’s something more nuanced—adults finding legitimate psychological benefits in play.

When Parent Collections Meet Family Life

I’ve seen this play out with my own kids in unexpected ways. The building set I bought “for the family” that somehow ended up in my office. The trading cards my husband started collecting that now fill two binders. The question that inevitably follows: Mom, why can’t we play with your Legos?

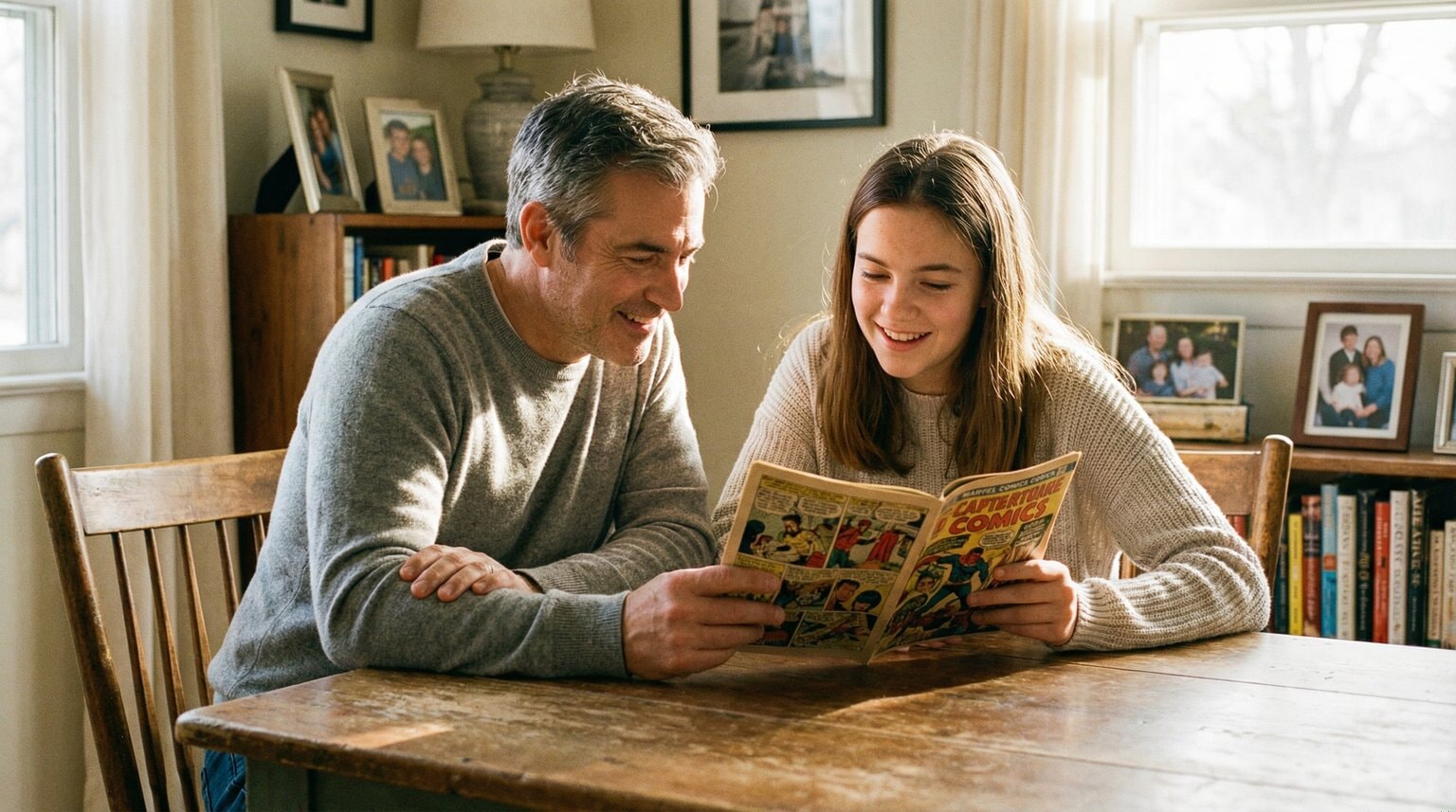

The concept of “horizontal parenting” offers a helpful reframe for thinking about this tension.

“They’ve become a really good way to be a parent on a horizontal level. Rather than talking down to [my son], we can sit together and be on the same level.”

— Dr. Richard Courtney, Head of Business Entrepreneurship and Finance, University of East London

This “horizontal parenting” concept—sitting alongside children rather than lecturing from above—suggests that parent toy ownership isn’t inherently selfish. It can create genuine connection points. When you’re both equally invested in completing a build or trading cards, something shifts in the dynamic.

But let’s be honest: there’s a difference between sharing interests and competing for the same toys.

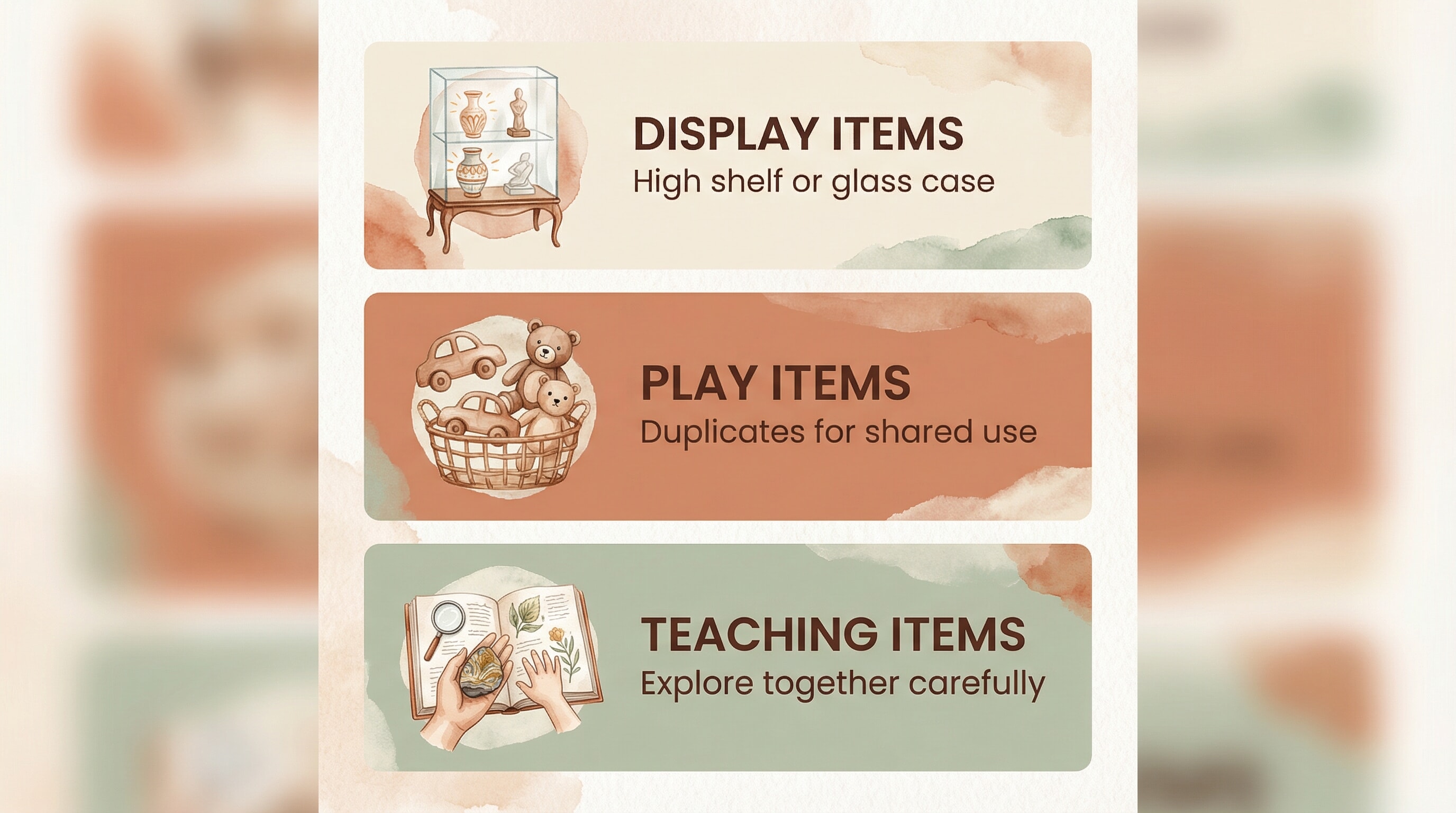

In my house, this looks like clear categories:

- Display items: get physical separation—a high shelf, a glass case, a designated room

- Play items: are duplicates or specifically purchased for shared use

- Teaching items: are collectibles we explore together but handle carefully

For younger children, physical boundaries communicate more effectively than lengthy explanations. My 4-year-old doesn’t fully grasp “this is Mommy’s special toy” as a concept—but she absolutely understands “the shelf you can’t reach.”

For older kids, the conversations become more nuanced. Explaining that adults have hobbies just like children do—and that some things are for looking while others are for playing—lays groundwork for understanding navigating tricky gift situations in their own lives.

The Line Between Hobby and Problem

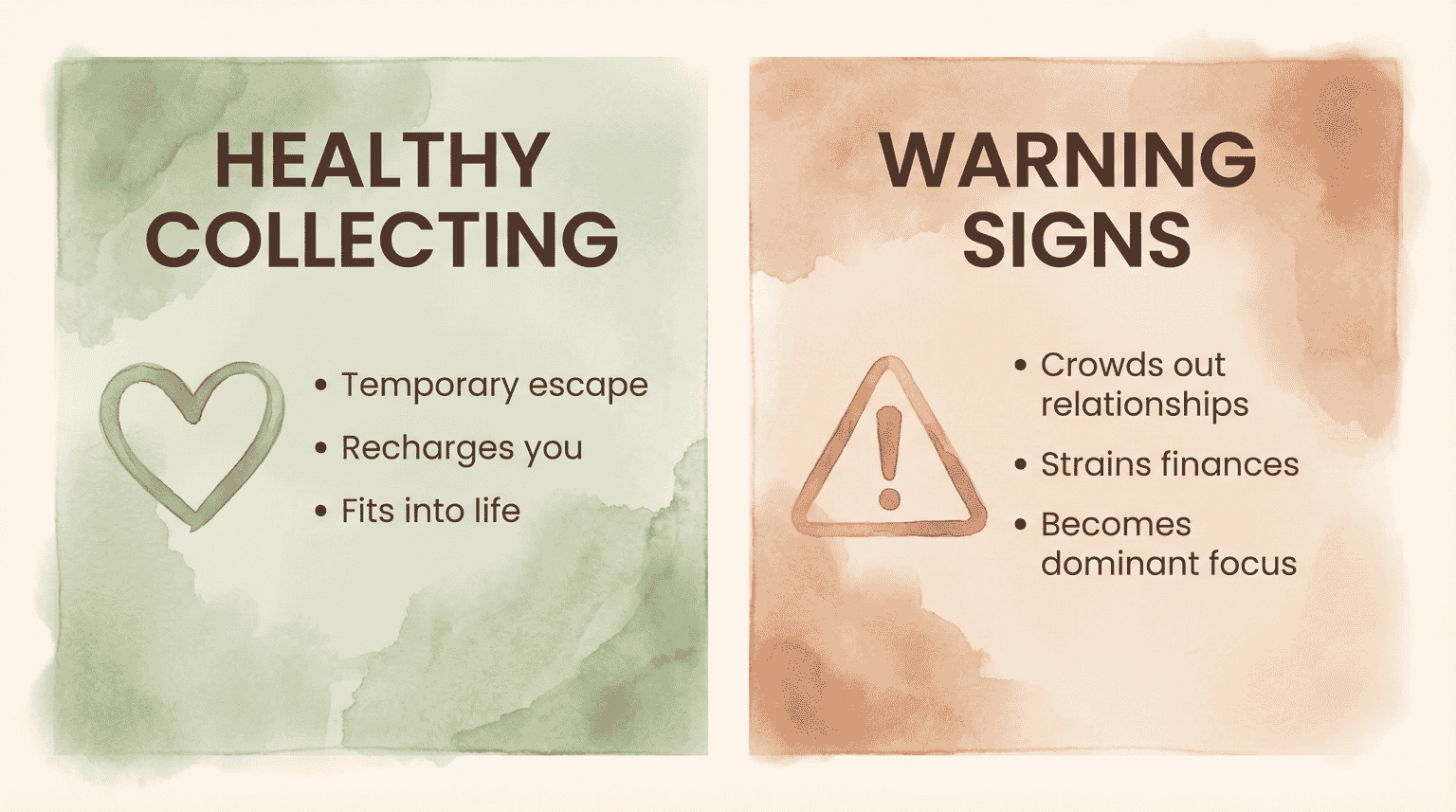

Here’s where I need to be direct. The research on kidulting is largely positive—but psychologists do draw boundaries.

“There’s a big difference between a trip down memory lane and setting up residence on memory lane. When it becomes kind of a fixation that seems to permeate throughout their whole life… that would be something, as a psychologist, I would at least begin to ask questions about.”

— Dr. Chloe Carmichael, Clinical Psychologist

Professor Krystine Batcho of Le Moyne College adds nuance: play might initially serve as an escape from burdens, but given a chance, play can also revive feelings of awe as ordinary things are seen through curious eyes from a new perspective.

The distinction matters. Healthy kidulting is temporary, bounded, and ultimately recharging. Problematic collecting crowds out relationships, strains finances, or becomes the dominant focus of daily life.

Questions worth asking yourself:

- Does my collecting energize me for adult responsibilities, or help me avoid them?

- Is spending on my collection impacting family financial priorities?

- Am I more excited to engage with my toys than with my family members?

- Would I describe my collecting as something I enjoy or something I need?

Temple University psychologist Kathy Hirsh-Pasek offers this guidance: toys “can’t be a substitute for humans. But if these toys become a way to get humans to play with other humans again, I’m all for it.”

That’s the litmus test. Does your hobby bring people together or push them apart?

Building Bridges, Not Walls

The best outcome I’ve observed—both in research and in my own home—is when kidult interests create family connection rather than family tension.

Trading card games rank among the top kidult categories, and they’re inherently social. Building sets require patience and problem-solving that cross age boundaries. Action figures and collectibles from franchises like Star Wars or Marvel often mean multiple generations share the same cultural touchpoints.

The psychology of fandom helps explain why these shared interests matter so much.

“It’s not really the object itself that matters most but rather what it represents to us. Associating with a particular group and feeling part of that group gives us a sense of being accepted and belonging which is incredibly powerful.”

— Dr. Julie Kirkham, Senior Lecturer, University of Chester

This sense of belonging extends to families. When parents and children share genuine enthusiasm for the same franchise, conversation flows more easily. When a teenager realizes their parent actually understands why that particular Pokémon card matters, something shifts. This connects to broader patterns in how gift-giving culture has evolved—we’re increasingly seeking gifts that strengthen relationships rather than just check boxes.

What if your child rejects your nostalgic interests entirely? That’s healthy too. Your 12-year-old rolling their eyes at your vintage Transformers isn’t a failure—it’s age-appropriate differentiation. The goal isn’t forcing shared interests but creating openings for connection.

The Permission Slip You Didn’t Know You Needed

Here’s what I keep coming back to: the question isn’t “Is buying toys for myself okay?” The research overwhelmingly says yes—for stress relief, for mental health, for nostalgia’s documented benefits.

The better question is “How am I doing this?”

Does your collection create joy without creating conflict? Does it open doors with your kids or close them? Does it recharge you for adult responsibilities or replace them?

If you’re reading this while eyeing that Lego set you’ve been wanting—or wondering whether to feel guilty about the building set currently taking over your dining room table—consider this your permission slip. With healthy boundaries, kidulting isn’t immaturity. It’s one more way adults navigate an increasingly stressful world.

My 17-year-old still gives me a look when I announce a new addition to my collection. But last week, she sat down next to me anyway. “Show me how this works,” she said. And for an hour, we weren’t parent and teenager. We were just two people building something together.

Frequently Asked Questions

Should parents feel guilty about buying toys for themselves?

Psychologists say no—within reason. Dr. Clay Routledge notes that nostalgic reflection helps adults cope with stress and maintain emotional balance. The question isn’t whether you buy toys, but how collecting fits into your broader life and family relationships.

Can kidult hobbies actually help parent-child relationships?

Yes. Dr. Richard Courtney describes collecting as “a really good way to be a parent on a horizontal level”—sitting together as equals rather than talking down to children. Shared interests in trading cards, building sets, or collectibles can create genuine connection opportunities.

When does toy collecting become a problem for parents?

Clinical psychologist Dr. Chloe Carmichael suggests watching for fixation that “permeates throughout their whole life.” Warning signs include: collecting that substitutes for human relationships, spending that impacts family financial priorities, or hobby involvement that crowds out parental responsibilities.

What if my child wants to play with my collectibles?

This is a natural tension in kidult households. Options include: designating some items as “display only” with physical separation, having duplicates for shared play, and creating age-appropriate collecting activities together. For younger children, physical boundaries communicate more effectively than explanations.

What toys do adults buy most often?

According to industry data, top kidult categories include trading card games (especially Pokémon), building sets like Lego, action figures and collectibles, and entertainment-licensed products from franchises like Star Wars and Marvel. Squishmallows and Funko Pop! figures also rank among bestsellers for adult consumers.

What About You?

Are you a “kidult” buyer? I’d love to hear what toys you’ve purchased for yourself—and whether you share them with your kids or keep them as display-only collections. No judgment here.

Your kidult confessions help other parents feel less alone in this.

References

- Adults Driving Surge in Toy Sales as ‘Kidult’ Trend Grows – 2025 CTV News coverage of Canadian kidult market trends

- Toys Aren’t Just Child’s Play: Mattel, Lego and Others Find ‘Kidulting’ – Los Angeles Times industry analysis with Circana data

- In Defence of Kidulting – New Humanist exploration of psychological benefits

- Why Kidults Are Rediscovering the Joy of Toys – BBC Bitesize UK market research and mental health findings

- Nostalgia as Self-Care: Embracing the Kidult Culture – Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking editorial on nostalgia psychology

Share Your Thoughts