Here’s a number that stopped me mid-coffee: University of Michigan researchers found the average child receives about 40 pounds of new toys every year. The typical playroom? Holding 110 pounds of plastic. The one-in-one-out rule is the simplest fix I know—and after implementing it with eight kids, I’ve figured out how to make them actually buy in.

Key Takeaways

- Kids are far more willing to donate toys when they choose which one goes—ownership transforms resistance into cooperation

- Create a simple “going away party” ritual to turn toy departure into celebration rather than loss. (Our donation box system makes this easier.)

- Use the 2-question filter: Can it be played with multiple ways? Will it grow with your child?

- Age-specific strategies matter—a 3-year-old needs guided choices while a 6-year-old can decide independently

How the Rule Works

The mechanic is straightforward: when a new toy enters your home, one existing toy leaves—donated, stored, or passed along. The key is announcing this before the new toy arrives. “Your birthday present is coming tomorrow—which toy do you think is ready for a new home?”

That 40-pound annual average isn’t just clutter—it’s overwhelming for kids and parents alike. The one-in-one-out rule creates a natural brake on accumulation without requiring massive decluttering sessions.

Think of it as sustainable toy management. Instead of periodic purges that feel punishing, you’re building an ongoing habit that keeps things balanced year-round.

Two smart exceptions: Collected sets (like LEGO themes being built over time) and genuinely sentimental items can be exempt. Without exceptions, you’ll fight battles that aren’t worth winning.

The visual is simple because the concept is simple. One arrives, one departs. No complicated systems to track, no apps to download, no spreadsheets required.

Three Ways to Make Kids Love It

Let them be the decider. Research on children’s inhibitory control shows kids are far more willing to part with toys when they choose which one goes. My 6-year-old will donate three toys unprompted if she’s in charge—but try to remove one yourself? Absolute meltdown.

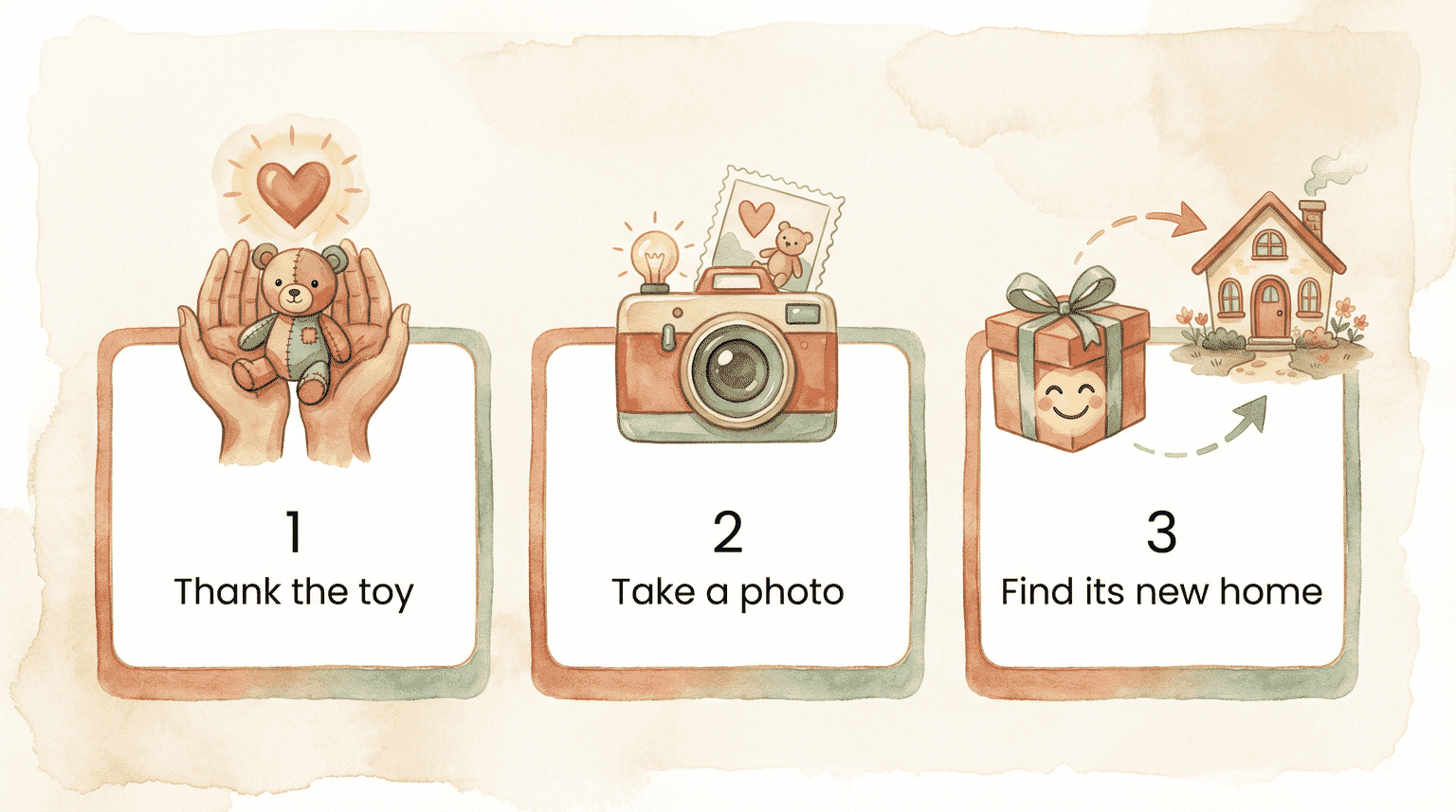

Create a “going away party.” This sounds silly until you try it. We thank the toy for its service, talk about who might love it next, and sometimes take a final photo together. It transforms loss into celebration.

Donation destinations become part of the story: “Your truck is going to help a kid who doesn’t have many toys.”

Connect old to new. Frame the outgoing toy as making room for the exciting arrival. “This toy is ready for its next adventure so your new one has a special spot.” Suddenly departure becomes part of the anticipation.

Here’s the thing—kids aren’t inherently hoarders. They learn to hold on tight when they feel things are being taken from them. Give them agency, and that grip loosens naturally.

Quick Age Guide

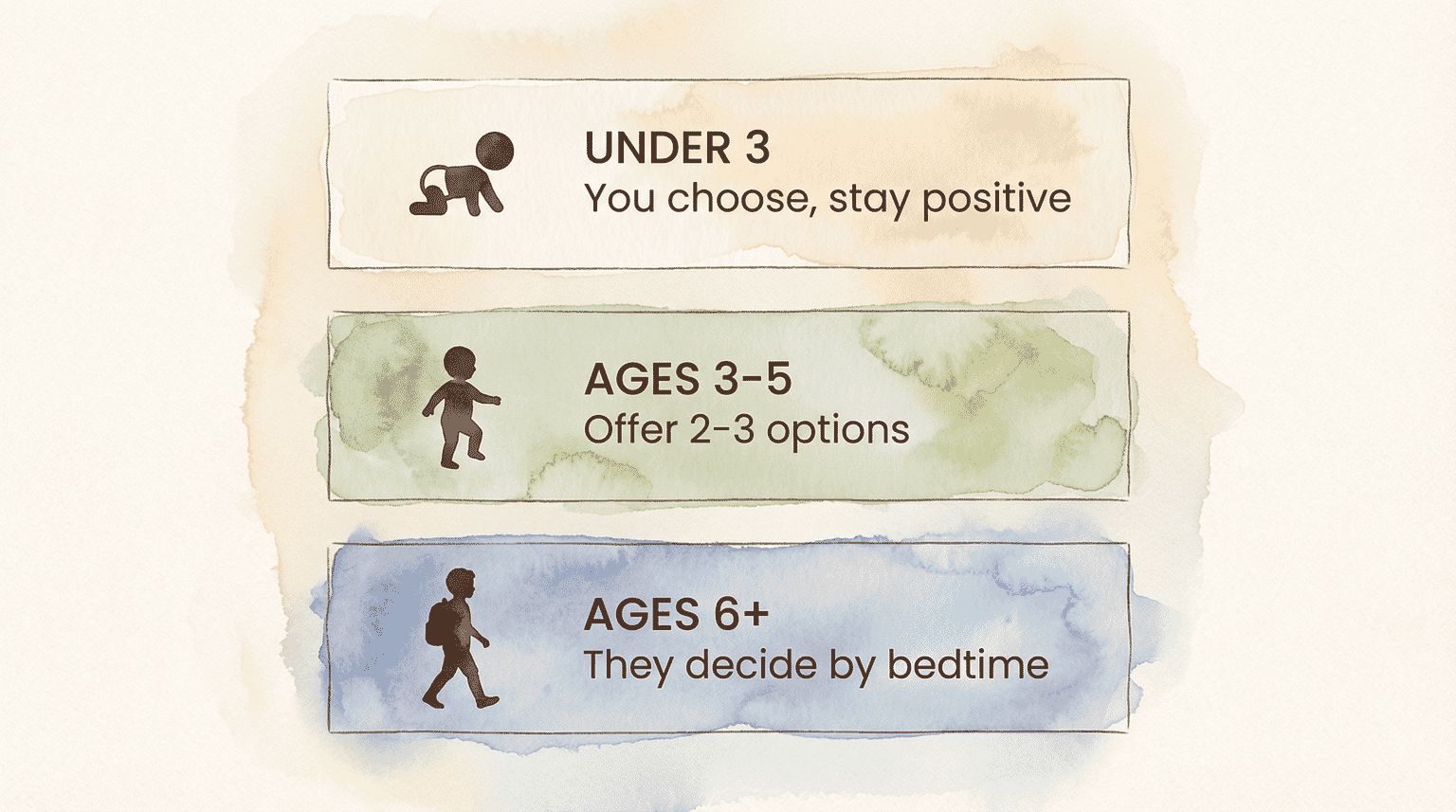

- Under 3: You make the selection, but present it positively: “This toy is going to help another toddler!”

- Ages 3-5: Guided choice works best. Research suggests children this age are still developing the decision-making skills for open selection, so narrow the field to 2-3 options.

- Ages 6+: Independent choice with a time limit. “Pick by bedtime” prevents endless deliberation.

The developmental piece matters more than most parents realize. A 4-year-old genuinely doesn’t have the cognitive capacity to evaluate an entire toy collection. Narrowing options isn’t limiting their autonomy—it’s scaffolding their decision-making skills.

And honestly? Even adults struggle with too many choices. Two or three options hits the sweet spot.

The 2-Question Keep-or-Go Filter

When my kids get stuck, I ask two questions:

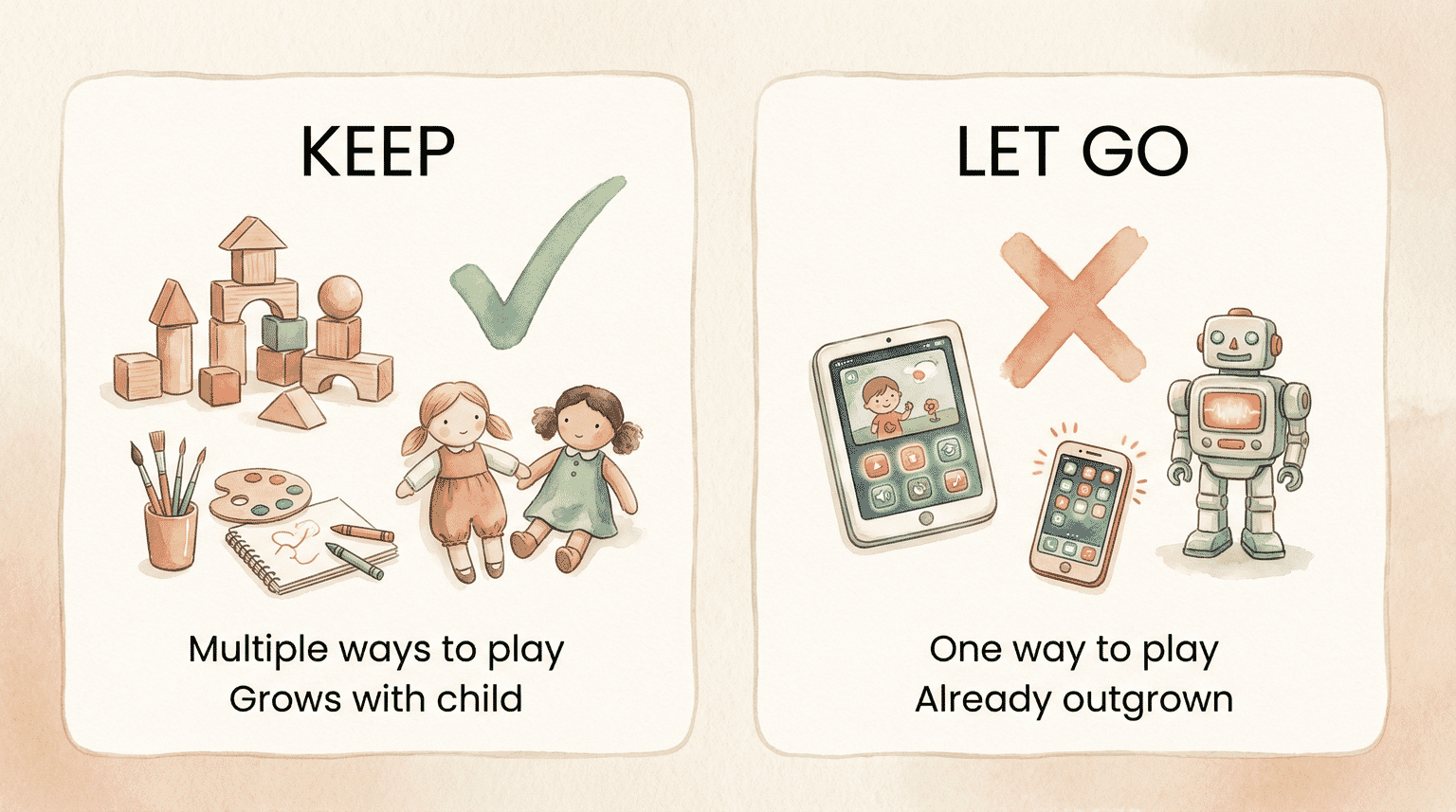

1. Can it be played with multiple ways?

2. Will it grow with you?

A 10-year study from Eastern Connecticut State University found that simple, open-ended toys with multiple parts inspire the highest quality play. Researcher Jeffrey Trawick-Smith puts it simply:

“Children are able to use them in many different ways.”

— Jeffrey Trawick-Smith, Professor of Early Childhood Education, Eastern Connecticut State University

Toys that pass both questions stay. Toys that don’t? Perfect candidates for the “going away party.”

The research backs what experienced parents already sense: that flashing electronic toy holds attention for days, but the wooden blocks get played with for years. Versatility beats novelty every time.

This filter also helps kids start thinking critically about their belongings—a skill that extends far beyond the playroom.

If you’re drowning in gifts from well-meaning relatives, our guide to managing the flood of incoming gifts tackles that conversation. And if one-in-one-out feels like just the start, a full toy rotation system might be your next step.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I get my child to let go of toys?

Give them ownership of the decision—children are far more willing to donate when they choose which toy goes. Create a simple ritual where you thank the toy together, making departure feel like a celebration rather than punishment.

At what age can children choose which toys to donate?

Around age 3, children can participate in guided choices when parents narrow options to 2-3 toys. By age 6, most can make independent selections with a reasonable time limit. Under 3, parents should choose—but framing it positively still builds the foundation.

What toys should I keep for my child?

Prioritize toys that can be played with in multiple ways and will grow with your child. Research consistently shows simple, open-ended toys hold attention longer than complex electronic alternatives.

Let that sink in. The goal isn’t fewer toys—it’s better toys, better played with, better loved.

I’m Curious

Does the one-in-one-out rule actually work at your house? Mine went through phases of accepting it and completely rebelling. Would love to hear how you’ve made it stick—or whether you’ve given up entirely.

I read every comment because toy decluttering strategies fascinate my librarian brain.

References

- University of Michigan School of Public Health – Research on toy accumulation and children’s environmental health

- TIMPANI Toy Study, Eastern Connecticut State University – Ten-year research on what makes toys developmentally valuable

Share Your Thoughts