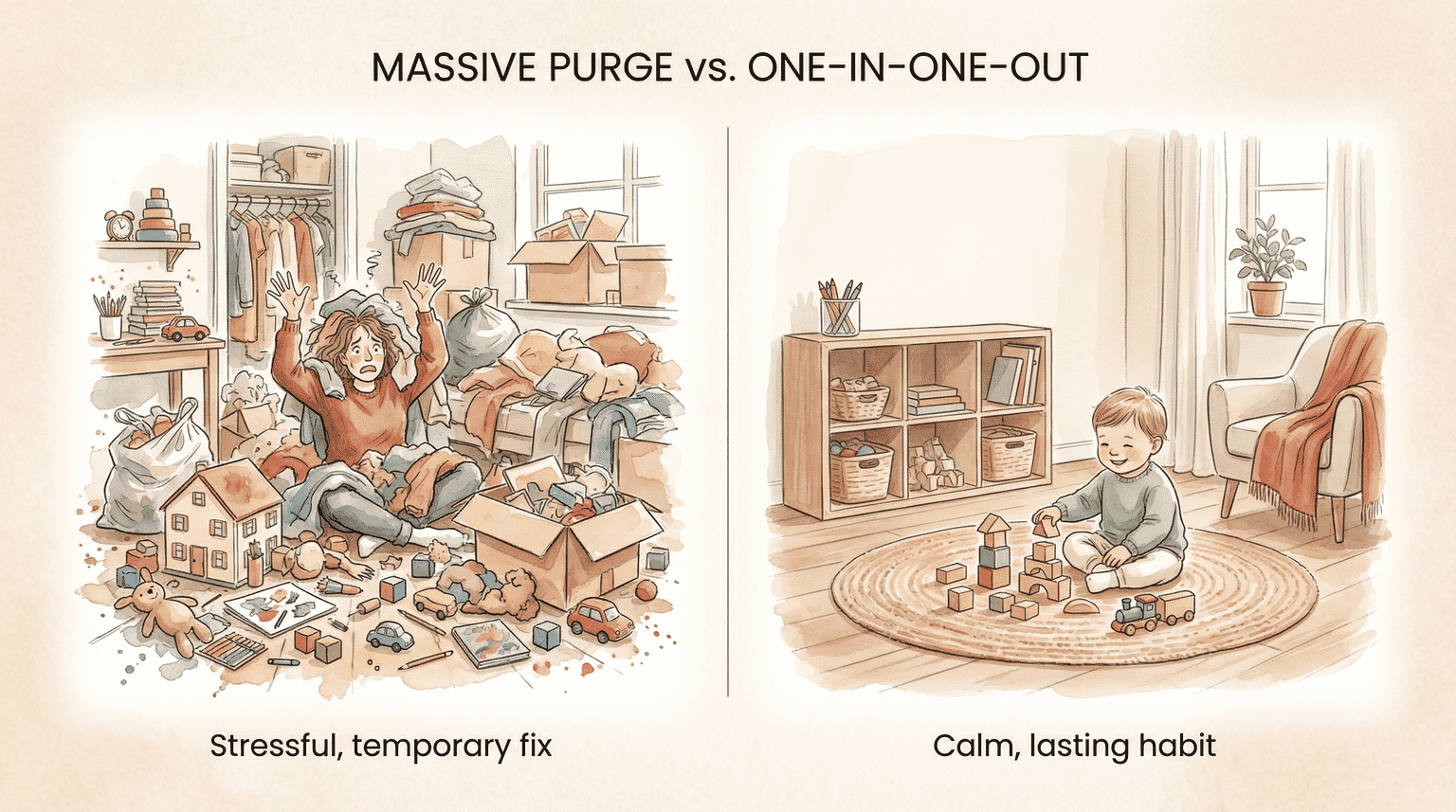

You’ve tried limiting toys. You’ve tried the massive declutter. And somehow, three months later, you’re back to stepping on LEGOs at 2 AM and wondering how the playroom exploded again.

I get it. With eight kids between ages 2 and 17, I’ve watched toy collections multiply like rabbits despite my best efforts. What finally worked wasn’t a dramatic purge—it was a simple maintenance system that prevents the chaos from returning in the first place.

Key Takeaways

- The one-in-one-out rule is maintenance, not a purge—one toy leaves for every new one that enters

- Children must choose what goes—forced removal always backfires and creates resistance

- Time it right: do the swap before birthdays and holidays, or within 24-48 hours of new toys arriving

- Age-appropriate conversations make all the difference—toddlers need simple choices, tweens need autonomy

- Twice yearly rhythm (before birthdays, before holidays) builds a sustainable lifelong habit

The One-In-One-Out Rule: What It Actually Means

Here’s the principle: for every new toy that enters your home, one existing toy leaves. That’s it.

The Art of Education University’s organizational research defines it clearly: “For every new item brought into the classroom, remove an old or unused one. This habit keeps your space balanced and ensures you’re only adding items that truly serve your teaching goals.”

Swap “classroom” for “playroom” and “teaching goals” for “your child’s developmental and play needs,” and you have the framework.

“For every new item brought into the classroom, remove an old or unused one. This habit keeps your space balanced and ensures you’re only adding items that truly serve your teaching goals.”

— The Art of Education University

What makes this different from general decluttering? It’s maintenance, not a massive purge. You’re not asking your child to part with twenty toys at once. You’re building a sustainable habit—one decision at a time.

How to Make One-In-One-Out Work in Your Home

The rule sounds simple. Implementation is where most families stumble. Here’s what I’ve learned actually works:

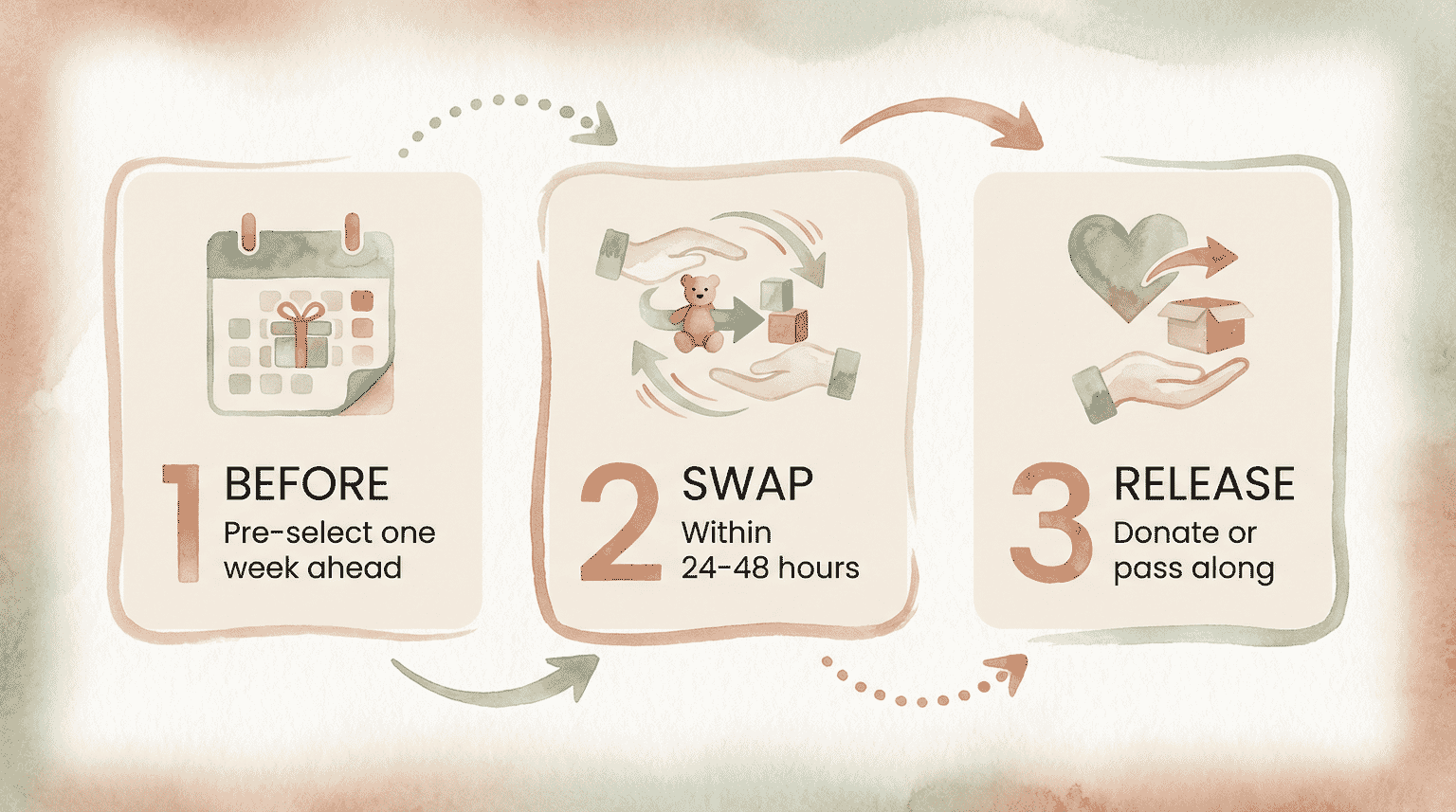

Before the New Toy Arrives

The best time to implement one-in-one-out is before the new toy shows up—ideally a week before birthdays or holidays. This is the proactive approach, and it prevents the emotional overload of asking a child to give something up while they’re still clutching their shiny new thing.

I call it “pre-selection.” Sit with your child and say: “Your birthday is coming up. Let’s make sure there’s room for your new presents by choosing one toy that’s ready to help another child.”

This framing matters. You’re not taking something away—you’re making space for something exciting.

The Swap Moment

If you didn’t do it beforehand, complete the swap within 24-48 hours of the new toy arriving. Wait longer, and the new toy becomes “just another toy” without the motivational power.

Do the decision-making in the play space—not abstractly while scrolling through mental toy inventories. When kids can see and touch their options, they make faster, more confident choices.

And this is crucial: the child chooses what goes. I’ve watched this fail spectacularly when parents select the “out” item. My 6-year-old will happily part with a toy she hasn’t touched in months—unless I suggest it, at which point it becomes her most treasured possession. Autonomy is everything.

Here’s the hard truth: forced removal always backfires. When you pick the toy that goes, you create resistance and attachment to things they’d otherwise happily release.

Let them lead. Even if their choice doesn’t make sense to you, honoring their autonomy builds trust—and makes the next swap easier.

Where the “Out” Item Goes

For younger kids, donation framing works beautifully: “This toy gets to make another child really happy.” My 4-year-old loves imagining another kid playing with her old toys.

For older children (8+), consider consignment or resale—it teaches that belongings have real value and connects effort to outcome. My 12-year-old is more willing to part with toys when she knows the money goes toward something she wants.

Broken or incomplete items? Straight to recycling, no guilt required. A puzzle missing three pieces isn’t serving anyone.

Getting Your Child On Board (Without the Battle)

Here’s what the research doesn’t tell you: the rule only works if your child participates willingly. Forced decluttering backfires every time. I’ve seen it with my own kids—resistance creates attachment to things they’d otherwise happily release.

Age-Appropriate Conversation Starters

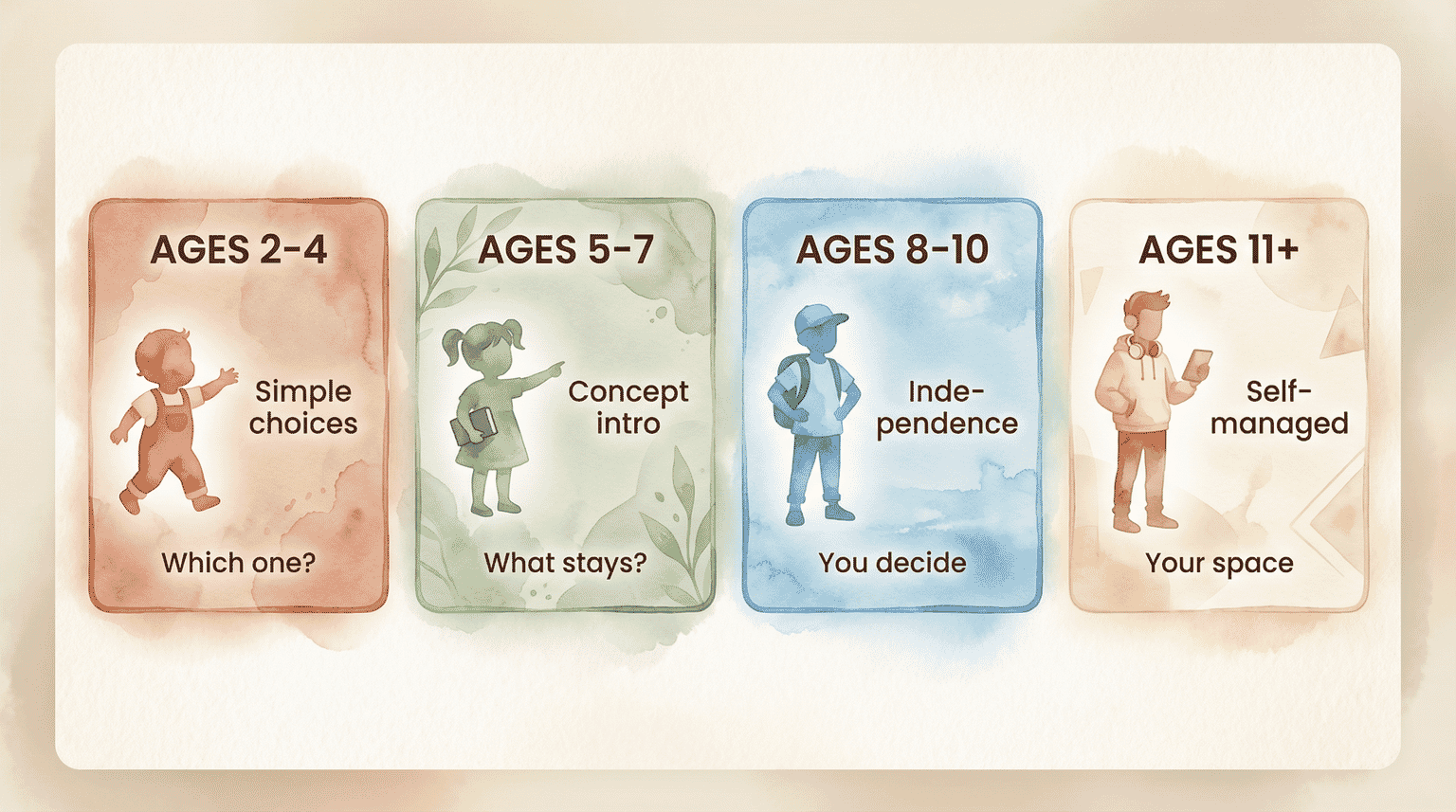

The way you introduce this depends entirely on your child’s developmental stage.

Ages 2-4: Keep it simple and concrete. “Your toy box has room for one special new friend. Which toy is ready to go help another child?” Offer two specific options rather than an open-ended question—decision fatigue is real for toddlers.

Ages 5-7: They can grasp the concept now. “Every toy in your room gets played with because we make room for what you love most. What should stay, and what’s ready for a new home?”

Ages 8-10: Appeal to their growing independence. “You get to decide what stays. What do you actually play with?” My 10-year-old responds well to being treated like the expert on her own belongings.

Ages 11+: By this point, if you’ve been doing this consistently, they often manage it independently. If you’re starting fresh with a tween, try: “Your space, your stuff, your call—but the rule is one thing out for every new thing in.”

When They Say “I Love ALL My Toys”

You’ll hear this. Guaranteed. Here’s what works:

The favorites reframe: “I know you love lots of toys! Let’s find the ones you love most—the ones you’d grab first if we could only keep five.”

The trial separation: For kids who genuinely can’t decide, try a two-week storage test. Box up the undecided items. If they don’t ask for something in two weeks, it’s ready to go. (In my experience, they rarely ask.)

Focus on what they’re gaining: “Making room means your favorite toys are easier to find and you have more space to actually play.” Children respond better to addition than subtraction.

If you’re interested in exploring teaching children about gift values more broadly, this same autonomy-first approach applies there too.

Making the “Out” Decision Easier

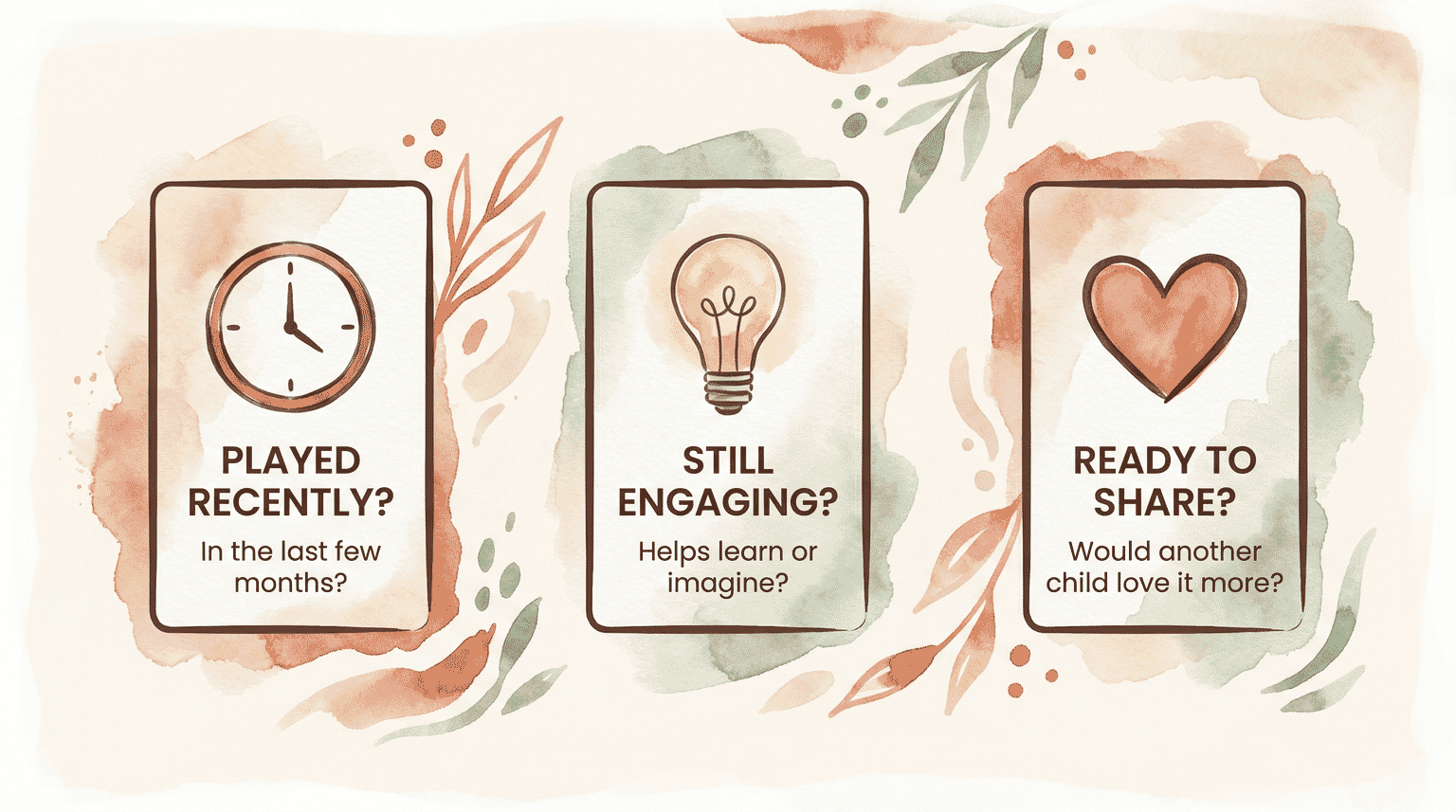

Even with buy-in, the actual choosing can feel overwhelming. I’ve adapted three decision-making questions from organizational research that work surprisingly well:

- “Have you played with this in the last few months?” Not years—months. Kids cycle through interests quickly.

- “Does this toy help you learn or imagine new things?” This gets at whether it’s genuinely engaging or just taking up space.

- “Would another child enjoy this more than you do right now?” This reframes giving away as generosity, not loss.

The “broken or incomplete” automatic-out rule: If it’s missing pieces, doesn’t work properly, or is damaged beyond play value—it goes without discussion. No guilt, no deliberation.

The exception box: Some items carry genuine sentimental weight. Allow 2-3 items in an “exception box” that don’t count toward the rule. But be firm on the limit—everything becomes sentimental if there’s no boundary.

When One-In-One-Out Doesn’t Apply

I’m a realist. Some categories don’t fit neatly into this framework:

Building collections that work together. LEGO sets, train tracks, magnetic tiles—these are meant to combine. A “set” counts as one item, not fifteen.

Consumable craft and art supplies. Markers dry out. Paper gets used. These cycle naturally and don’t need the rule.

Books. I keep books on a separate system entirely. If your child’s bookshelf is overflowing, consider starting with a toy rotation system for toys while leaving books unlimited—literacy is the one area where “too many” isn’t really a problem.

Genuine developmental growth. Sometimes children legitimately need more toys—when they’ve aged out of infant items and into preschool play, for instance. Use judgment here. The rule prevents accumulation, not appropriate expansion.

Building the Habit That Lasts

The secret isn’t perfect implementation—it’s predictable rhythm. We do one-in-one-out before birthdays and before the holiday season. Twice a year, consistently. The kids know it’s coming, so there’s no surprise or resistance.

Organization experts note that maintaining a balanced environment—where new items are offset by removing unused ones—prevents clutter from re-accumulating after initial decluttering efforts.

The rhythm is what makes this sustainable rather than a one-time event you’ll need to repeat.

Over time, I’ve watched the process shift from parent-led to child-initiated. My 15-year-old now clears things out before I even mention it. She’s internalized the habit. That’s the real goal—children who grow up making intentional choices about what they own.

Managing Gift-Givers

The trickiest part? Grandparents and relatives who show love through volume.

Keep it simple and appreciative: “The kids have so many wonderful toys already. We’re trying to teach them to really appreciate what they have. Would you consider an experience gift this year—or maybe contributing to something bigger they’ve been wanting?”

Most gift-givers want to make kids happy. Redirecting toward experiences or contributions to larger items (a bike, a special outing) still lets them feel generous without adding to the pile. For families considering rotating toys by age as a complementary strategy, this becomes even more manageable.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do you explain the one-in-one-out rule to kids?

Use age-appropriate language focusing on making room for what they love most. For ages 3-5: “Your toy box has room for one special new friend. Which toy is ready to go help another child?” For ages 7+, emphasize their control: “You get to decide what stays—what do you actually play with?”

At what age can children understand the one-in-one-out rule?

Most children can participate meaningfully around age 3, though conversations look different at each stage. Toddlers need simple either/or choices with parent guidance. By ages 5-7, kids understand the concept with light support. Children 8 and older can often manage independently once the habit is established.

Does the one-in-one-out rule actually work?

Yes, when implemented consistently. The key is making it a predictable rhythm—before birthdays, before holidays—rather than constant policing. Children must feel ownership over their choices; items removed against their will create resistance that undermines the whole system.

What do you do with items removed using one-in-one-out?

Three main paths: donation (frame positively as “making another child happy”), consignment or resale (for older kids who understand value), or disposal for broken items. Broken or incomplete toys can go directly to recycling without guilt.

Join the Conversation

Does one-in-one-out work at your house? I’d love to hear what’s made it stick—or what’s made it fall apart. Real implementation stories help other parents know what to expect.

Your one-in-one-out wins and fails help other families figure this out.

References

- The Art of Education University – Organizational research on the one-in-one-out principle and decision-making frameworks for maintaining balanced spaces

Share Your Thoughts