Your daughter spent thirty minutes watching unboxing videos yesterday. Today she needs the exact pink unicorn journal that “everyone has.” By next week? She’ll have moved on to rainbow slime, as if the journal never existed.

This isn’t random. It’s not even about the journal. What you’re watching is one of the oldest patterns in human psychology—one that social media has supercharged into something parents have never had to navigate before.

Key Takeaways

- Children don’t want objects because they’re inherently amazing—they want them because someone they admire demonstrated the object is worth wanting

- Social media creates a “hyper-mimetic environment” where kids rapidly cycle through unstable models of desire—explaining why wish lists rewrite themselves weekly

- Research shows phone bans alone don’t improve mental health because they fail to address the underlying social dynamics

- The key distinction: thick desires (sustained, skill-connected) versus thin desires (sudden, brand-specific, ephemeral)

- Awareness breaks the spell—when children understand how their desires form, they gain capacity to evaluate their wants rather than being driven by them

The Scene Every Parent Recognizes

Here’s a scenario researchers love to describe because it captures something essential about human nature: Place two identical toys in front of two preschoolers. The moment one child picks up a toy, the other child wants that specific toy—not the identical one sitting untouched. It’s as if the first child’s interest conferred some special status onto the object that the second child can’t resist.

I’ve witnessed this exact dynamic approximately eight thousand times in my house. My favorite version involved two stuffed animals at naptime. If my younger one chose the panda, suddenly my older child needed the panda—despite having ignored it for weeks.

Redirect the little one toward the teddy bear? Now the teddy bear was apparently her “heart’s desire all along.”

This isn’t about the toy. It’s about the other person wanting it.

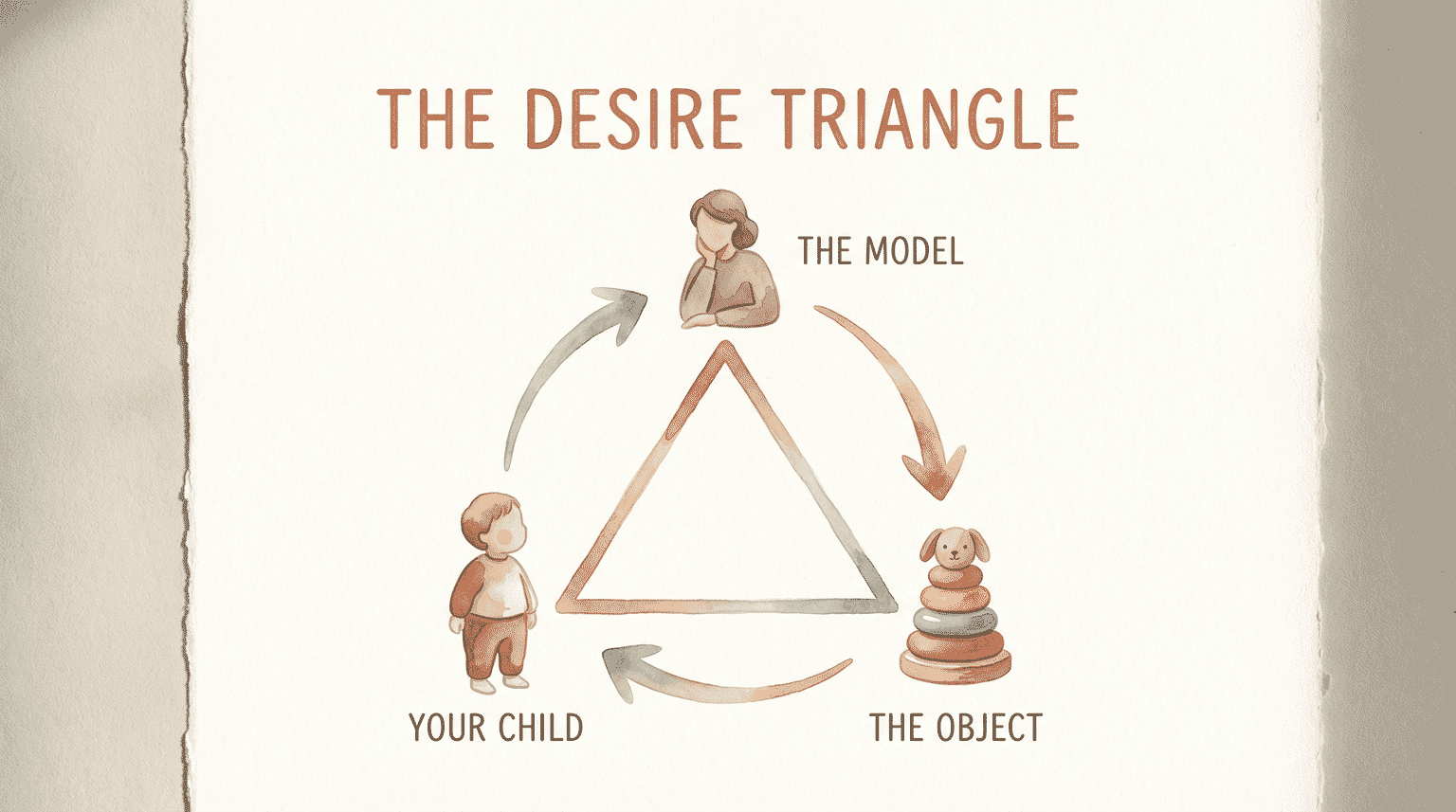

The Desire Triangle—How Wanting Actually Works

Philosopher René Girard spent his career mapping this territory, and his core insight still startles me: “Man is the creature who does not know what to desire, and he turns to others in order to make up his mind. We desire what others desire because we imitate their desires.”

We think desire works in a straight line—we see something, we want it. Girard called this the “Romantic Lie.” The truth is messier. Desire is triangular: there’s your child, there’s the object, and crucially, there’s the model—the person whose wanting makes the object desirable.

Here’s what makes this neurologically real: A 2021 analysis in Christian Scholars Review notes that imitation begins within hours of birth—replicated across over a dozen independent laboratories. Mirror neurons fire both when we perform an action and when we observe someone else performing it.

Even more striking, brain scans show that resisting group preferences activates neural patterns associated with physical pain.

Going against what others want literally hurts. This explains why “just ignore what your friends have” feels like impossible advice to children—their brains are wired to align with the group.

Why Social Media Makes Everything Worse

If mimetic desire has always existed, what’s different now?

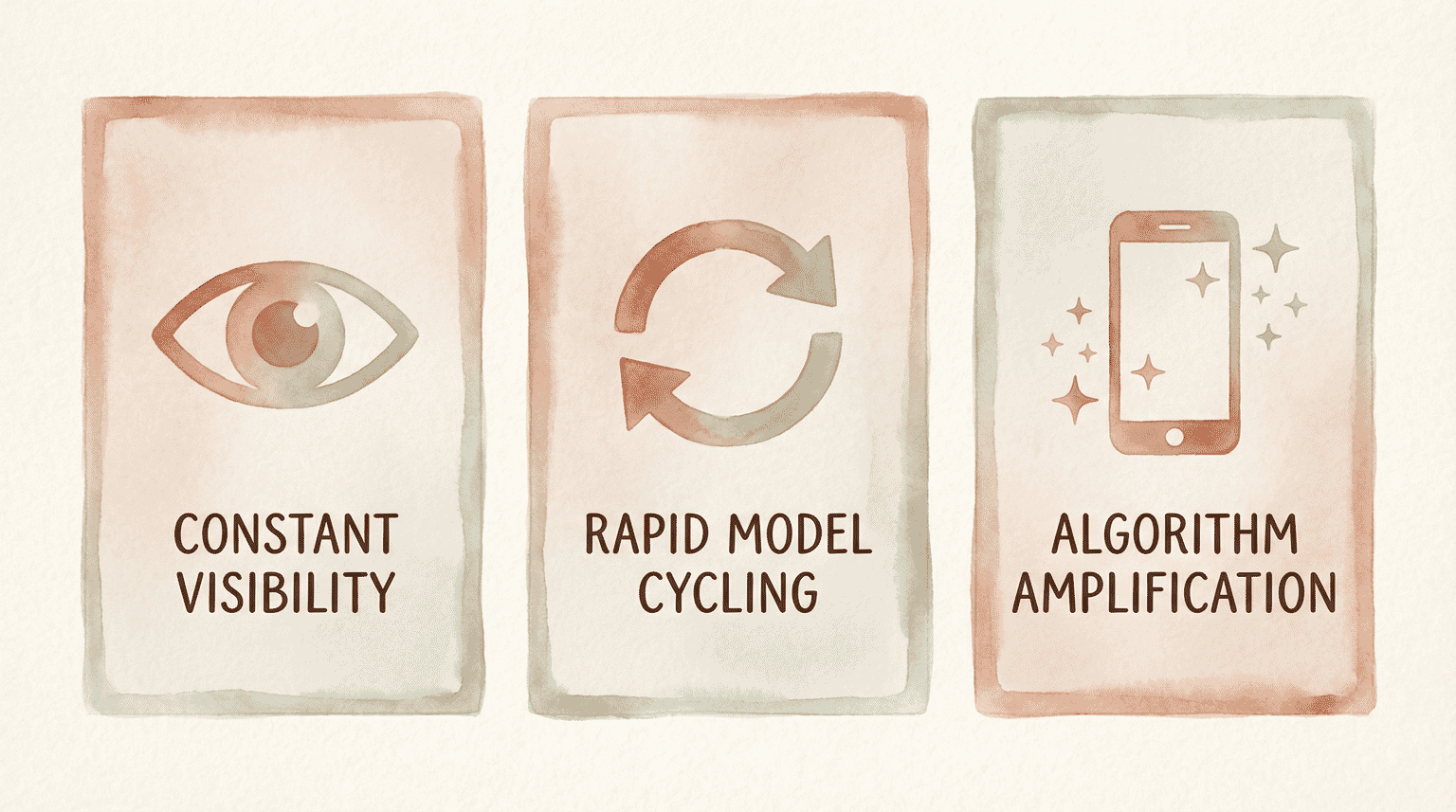

Researchers describe today’s digital landscape as a “hyper-mimetic environment” where young people “rapidly cycle through unstable models of desire.” The 2025 PMC analysis identifies three ways social media amplifies the mechanism:

- Constant visibility. Your child sees what peers have, what influencers recommend, what’s trending—all day, every day. FOMO isn’t just fear of missing out on events; it’s fear of missing out on wanting the right things.

- Rapid model cycling. Yesterday’s favorite YouTuber is replaced by tomorrow’s. Each new model brings new desires. This is why your child’s wish list seems to rewrite itself weekly.

- Algorithm-driven exposure. The more your child watches unboxing videos, the more the algorithm serves similar content. Desire gets amplified, reinforced, and multiplied.

This connects to how digital culture shapes gift expectations more broadly—the constant stream of content creates a baseline of expectation that previous generations never experienced.

The result? Children cycling through wants faster than ever before, powered by the same dopamine response that makes social media likes addictive. The wanting itself becomes a form of entertainment.

Why Phone Bans Don’t Work

Here’s where my librarian brain got hooked: the 2025 PMC research found that smartphone bans in schools “do not enhance students’ mental health” despite clear correlations between excessive phone use and poorer outcomes.

A February 2025 Lancet study confirmed this directly: “There is no evidence that restrictive school policies are associated with overall phone and social media use or better mental wellbeing in adolescents.”

Why? Because restriction doesn’t address the underlying mechanism. Take away the phone, and the mimetic dynamics within peer networks continue. Kids still compare. Still want what others have. Still cycle through desires based on social models.

The researchers put it directly: “The belief that simply restricting young people’s access to social media will eliminate [negative outcomes] is likely misguided, as it fails to address the underlying social dynamics and psychological mechanisms.”

What actually helps? Girard himself offers the key: “Mimetic rivalry loses its power only when it is exposed.”

Awareness breaks the spell. When children understand how their desires form—when the unconscious becomes conscious—they gain the capacity to evaluate their wants rather than being driven by them.

Thick vs. Thin Desires—A Parent’s Diagnostic Tool

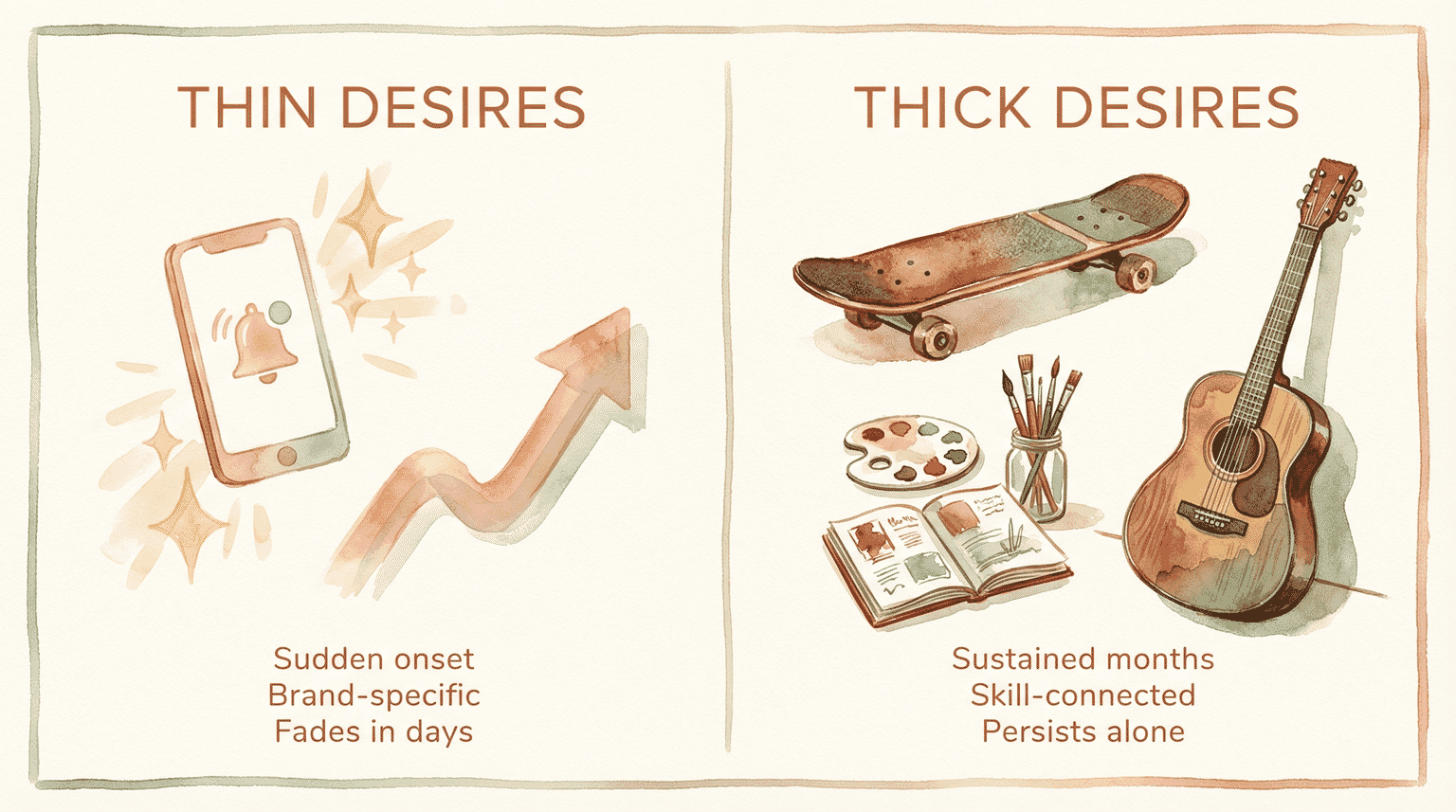

Luke Burgis, who applies mimetic theory to contemporary life, offers a framework I find genuinely useful. He distinguishes between thick desires (built up throughout life, connected to core identity, enduring) and thin desires (highly mimetic, ephemeral, “here today and gone tomorrow”).

As Burgis puts it: “Thin desires are blown away with a light gust of wind. A new model comes into our life. The old desires are gone. Suddenly, we want something else.”

Signs of thin desires:

- Sudden onset, often after seeing someone else with the item

- Brand-specific or influencer-connected

- Intense urgency that fades within days

- Child can’t articulate why they want it beyond “everyone has one”

Signs of thick desires:

- Sustained interest over weeks or months

- Connected to activities or skills they’re genuinely developing

- They can explain what they’d actually do with it

- Interest persists even without peer reinforcement

When my 10-year-old wanted a specific skateboard for months, kept watching tutorials, practiced on borrowed boards—thick desire. When my 8-year-old suddenly needed rainbow slime after one playdate? Thin. The slime lasted two days before becoming a sticky regret in the carpet.

Breaking the Pattern—What Actually Helps

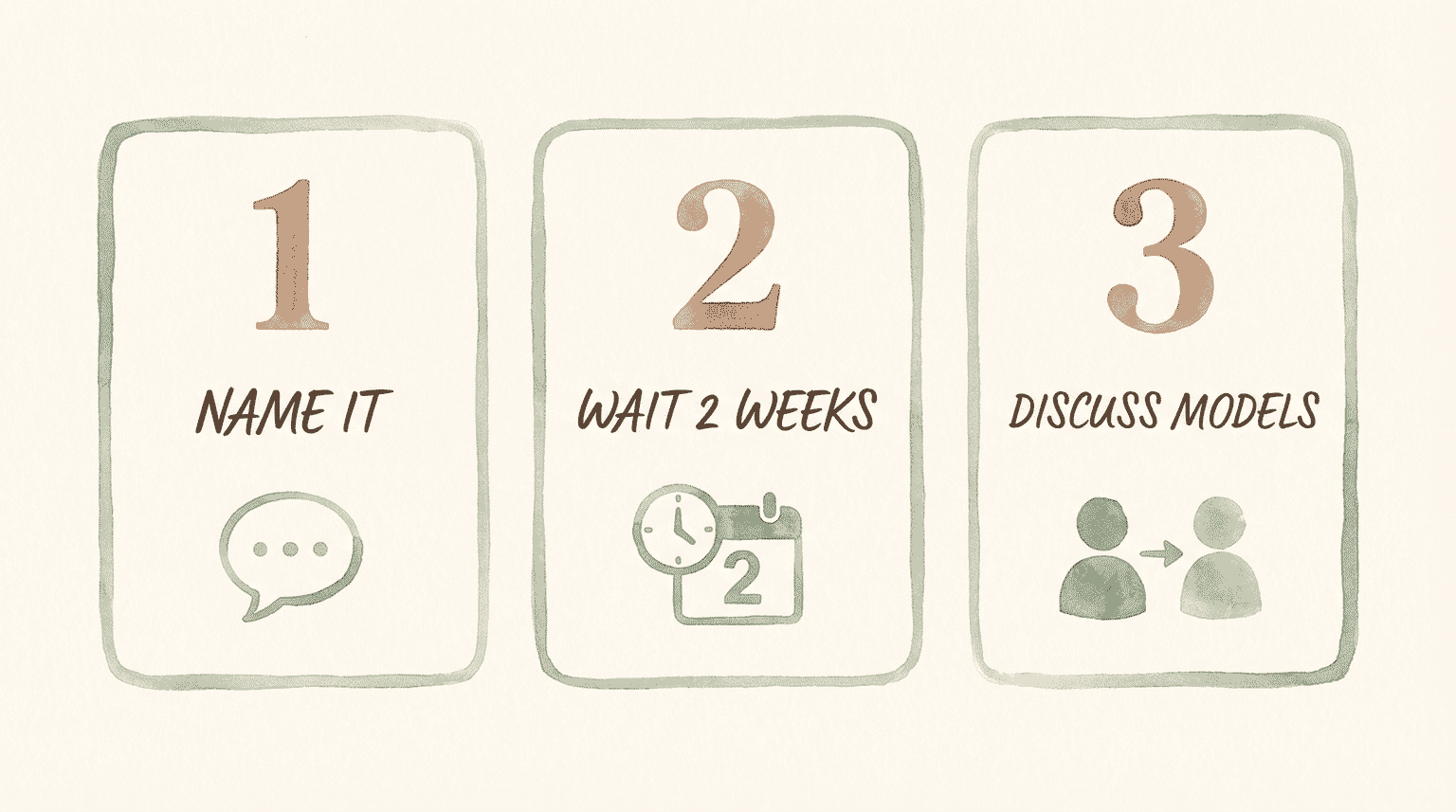

Understanding when mimetic desire becomes persistent requests is useful, but the deeper goal is helping children develop awareness of their own wanting. Here’s what works in my house:

Name it. Give the mechanism a name children can understand. “It sounds like you want this because Maya has it. Let’s think about whether you’d want it if she didn’t.” This simple reframe brings the unconscious process into awareness.

Introduce waiting periods. Thin desires evaporate; thick ones persist. A “wishlist waiting period” of two weeks reveals which wants are real. My kids know to add items to a running list rather than expecting immediate purchase. It’s remarkable how many items quietly disappear from the list.

Discuss models openly. Ask who they want to be like and why. “You really like what this YouTuber has—what is it about her you admire?” This conversation helps children recognize that they’re not really wanting the object; they’re wanting something the model represents.

Pre-exposure conversations. Before high-risk situations—birthday parties, holiday catalogues, YouTube time—acknowledge what’s coming:

“You might see toys there that suddenly seem amazing. That’s normal—our brains do that when we see other kids excited about things. Let’s talk about it after and see if you still feel that way.”

— Pre-party conversation example

Identify their actual interests. Help children discover what Parker Palmer calls listening to their life: “Before I can tell my life what I want to do with it, I must listen to my life telling me who I am.”

What does your child return to again and again, even without external prompting? Those are the thick desires worth cultivating.

The Deeper Gift

Understanding mimetic desire isn’t about eliminating it—that’s probably impossible and potentially undesirable. Imitation is how we learn, connect, and develop. The goal is helping children become aware of the mechanism so they can evaluate their desires rather than being unconsciously driven by them.

This awareness is itself a gift. Children who understand why they suddenly want what everyone else has are better equipped to recognize their genuine interests, resist manipulative marketing, and eventually choose their models intentionally rather than by algorithmic accident.

In my house, we’ve started calling it “borrowed wanting”—a phrase even my 6-year-old can understand. It doesn’t stop the wanting. But it gives us language to talk about it honestly.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does my child always want what their sibling has?

This reflects mimetic desire—children learn what to want by observing what others want. When your child sees a sibling enjoying something, their brain registers the object as valuable because someone else values it, not because of what it actually is. Research shows this pattern begins within hours of birth and explains why a toy ignored for months becomes essential the moment another child picks it up.

How does social media affect what kids want?

Social media creates a “hyper-mimetic environment” that dramatically accelerates desire formation. Constant visibility of what others have amplifies FOMO, rapid model cycling (influencers, peers, characters) introduces new desires continuously, and algorithms multiply exposure to desirable objects. The result is children cycling through wants faster than ever before.

Is it normal for kids to copy what their friends want?

Completely normal—and universal. Imitation is hardwired from birth, serving essential functions in learning and social connection. The goal isn’t eliminating mimesis but helping children become aware of it so they can evaluate their desires more consciously and choose worthy models intentionally.

How do I teach my child to be happy with what they have?

Rather than restricting exposure (which research shows doesn’t work alone), help children understand how desire actually forms. Name the phenomenon when you see it, introduce waiting periods that allow thin desires to fade, and ask questions about who they want to be like and why. Making the unconscious process conscious is what actually builds lasting contentment.

Over to You

Have you noticed mimetic desire at work in your house? I’m curious whether naming it—”you want that because you saw someone else want it”—has helped your kids recognize the pattern, or just annoyed them.

Your mimetic desire stories help other parents realize they’re not imagining this pattern.

References

- Mimetic Theory: A New Paradigm for Understanding the Psychology of Conflict – Foundational research on imitation from birth and mirror neuron evidence

- Imitation, Rivalry, and Escalation: PMC/NIH 2025 Analysis – Research on social media’s “hyper-mimetic environment” and why restriction alone fails

- Mimetic Desire and the Battle for Authenticity – Luke Burgis framework on thick vs. thin desires

- Help Children Understand Mimetic Desire – Practical application of the “Romantic Lie” concept for parents

- Lancet (Feb 2025) – Evidence that school phone bans don’t improve mental wellbeing

Share Your Thoughts