Your 4-year-old is melting down in the grocery checkout line. The promised cookie is coming—it’s literally being scanned right now—but “in one minute” might as well be “never.” You’re not raising an unreasonable child. You’re watching three different brain systems collide in real time.

Here’s what the research actually shows: children struggle with waiting because of how their brains work, how they perceive time, and how much practice they’ve had. Understanding these mechanisms won’t eliminate the checkout line meltdowns, but it transforms frustration into something closer to fascination.

At least, that’s what happened for me after my librarian brain couldn’t let this go without investigating.

Key Takeaways

- Your child’s brain literally lacks the hardware for patience—the prefrontal cortex won’t fully mature until their mid-20s

- Children experience time differently than adults—your “5 minutes” genuinely feels like forever to them

- Patience is learnable through practice—cross-cultural research shows kids who practice waiting regularly become remarkably good at it

- Early impatience doesn’t predict adult outcomes—environment and practice matter far more than innate traits

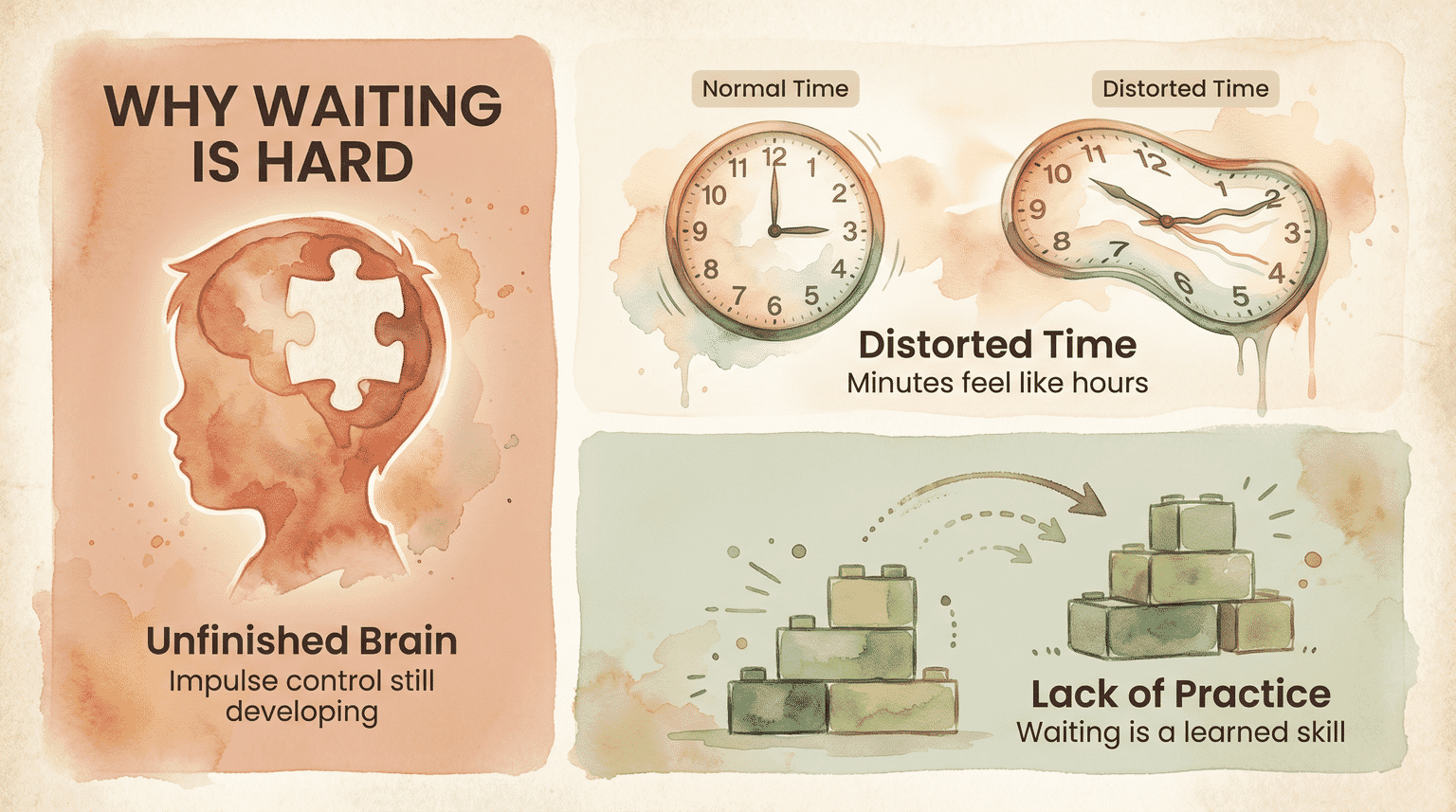

The Three Reasons Waiting Feels Impossible

When my 2-year-old screams because her snack isn’t ready this second while my 17-year-old patiently waits for college decisions, I’m watching the same three mechanisms at different stages of development.

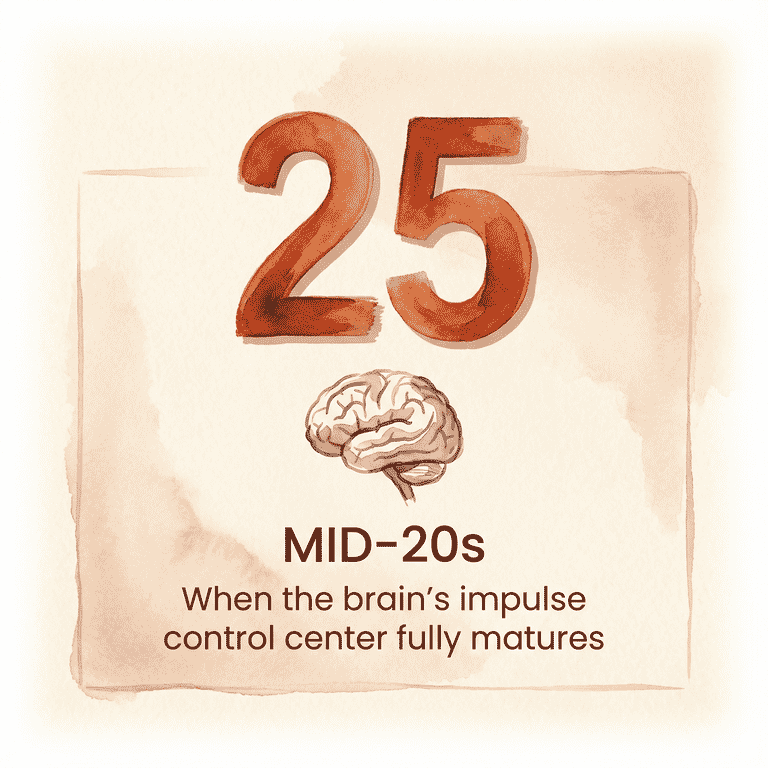

First, the unfinished brain: The prefrontal cortex—your child’s impulse control center—won’t fully mature until their mid-20s. They’re not refusing to wait; they literally lack the neural hardware.

Second, distorted time: Children and adults exist in what researchers describe as “different time streams.” Your “five minutes” is their eternity.

Third, the practice effect: Recent cross-cultural research reveals something surprising—children can wait remarkably well, but only in contexts where waiting is routine.

What’s Actually Happening in Their Brain

University of Michigan professor Pamela Davis-Kean puts it simply: “Patience is another name for self-regulation, which is both behavioral and emotional.” And self-regulation depends on brain structures that develop gradually throughout childhood.

The prefrontal cortex handles three core executive functions essential for waiting:

- Working memory: Holding the goal (“I’ll get two cookies if I wait”) in mind

- Inhibitory control: Suppressing the impulse to grab the cookie now

- Cognitive flexibility: Shifting attention away from the tempting reward

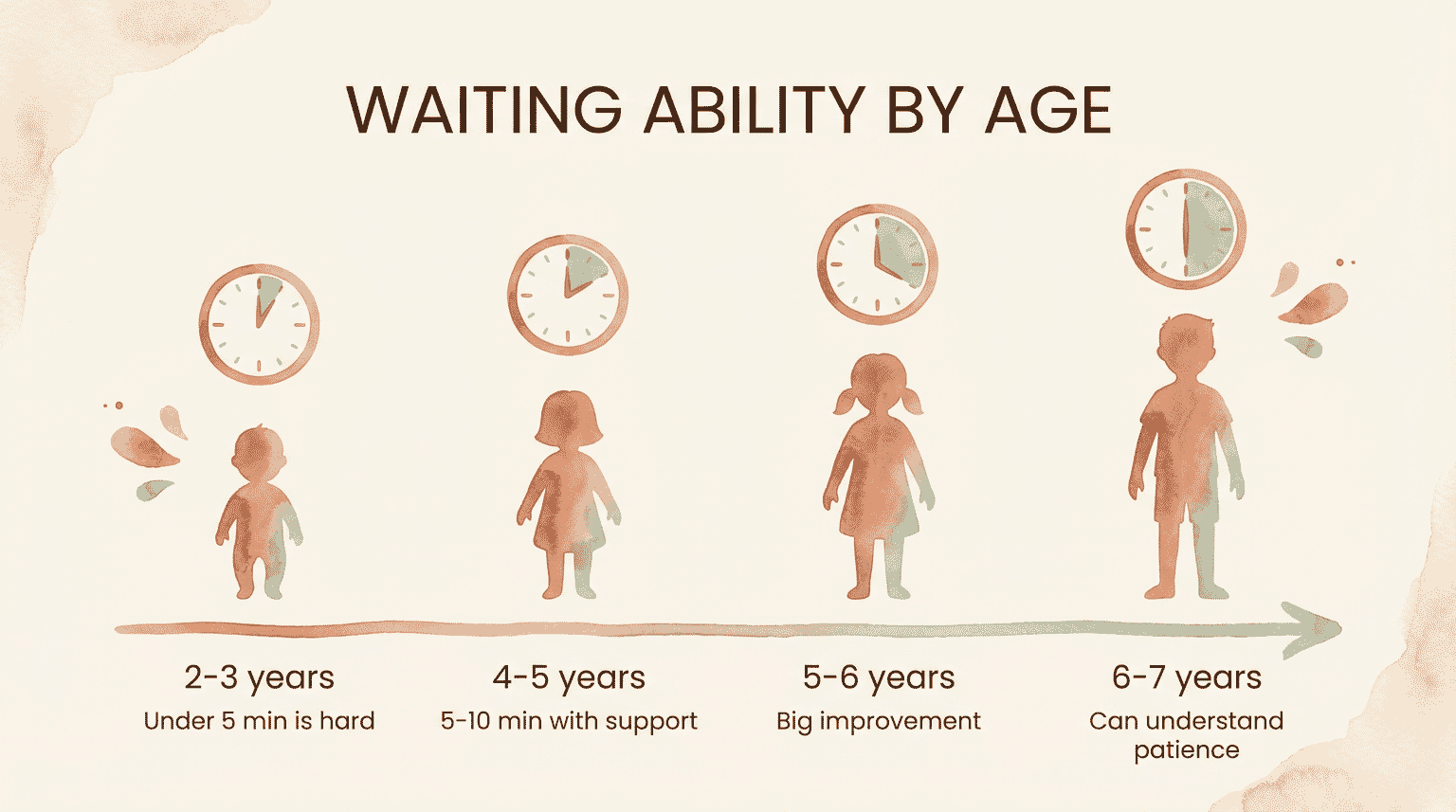

A 2021 cross-cultural study found that 3-year-olds have significant difficulty with delays over 5 minutes. By age 5, children show substantially improved waiting ability—but even they struggle when those executive functions get overwhelmed.

Here’s the critical distinction: your child isn’t choosing impatience. Penn State professor Pamela Cole explains that we live in a social world where we can’t have everything we want when we want it—and that’s where patience and self-control come in. But those skills require brain development that simply takes time.

Why Does 5 Minutes Feel Like an Hour to a 4-Year-Old?

When I tell my 4-year-old “dinner in 10 minutes,” she asks approximately 47 times if it’s ready yet. This isn’t defiance—it’s genuinely different time perception.

Young children lack the developed sense of temporal duration that adults take for granted. Without accurate time perception, “5 minutes” provides no meaningful information. It’s not a measurement; it’s just a word that means “not now.”

Research consistently shows this isn’t simply impatience—it’s a fundamentally different experience of time passing. What feels like a reasonable wait to you may genuinely feel endless to your child. This explains why “just wait” is such ineffective advice: you’re asking them to tolerate something they experience as unbearably long.

The good news? Time perception develops. Your teenager can wait for that college decision because they’ve developed the cognitive infrastructure to understand what “three months” actually means. Your toddler screaming for crackers hasn’t built that yet.

Can Any Child Learn to Wait? The Practice Effect

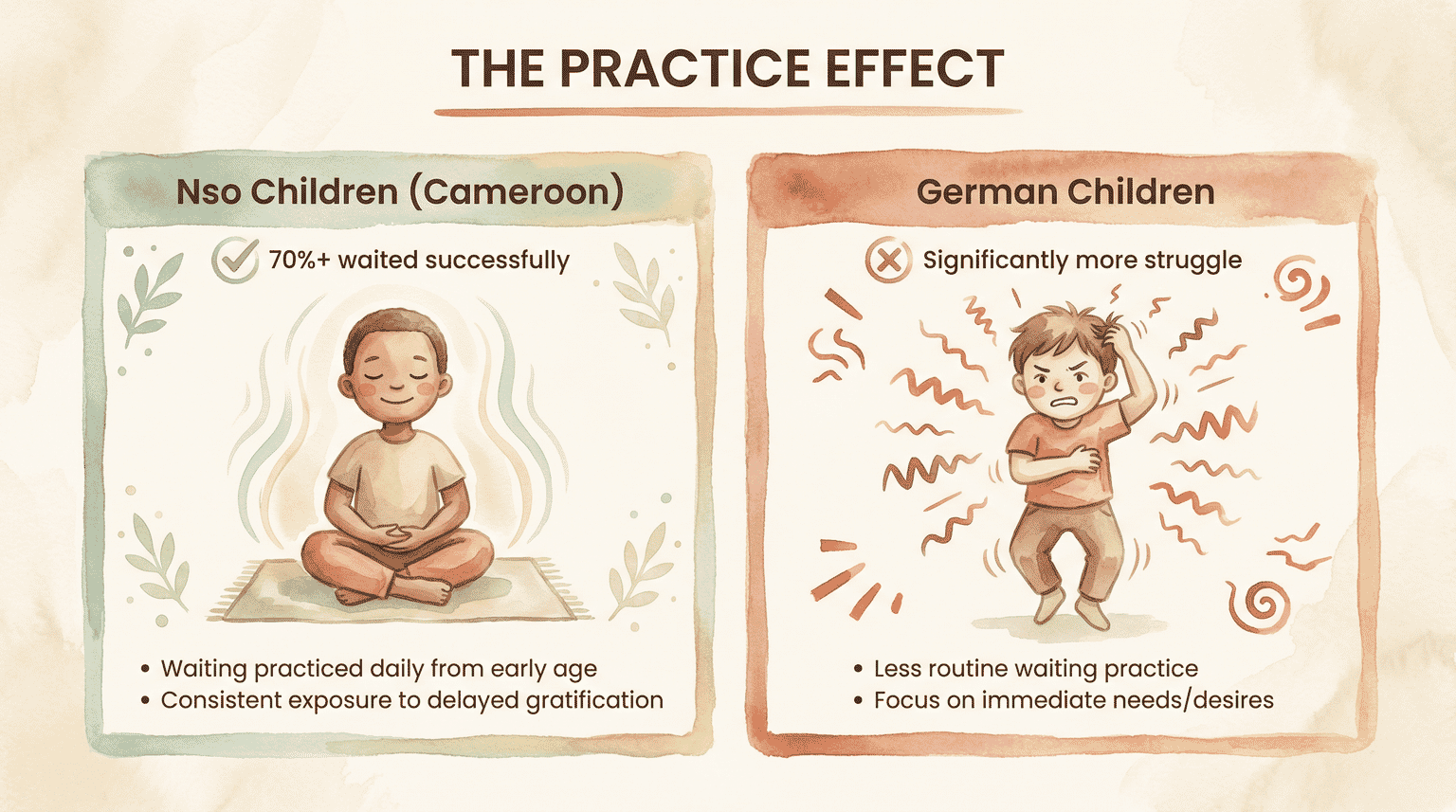

Here’s where the research gets genuinely surprising. A February 2025 cross-cultural study found that over 70% of Nso children from Cameroon could wait until the end of delay tasks—some even fell asleep while waiting. German children in the same study struggled significantly.

Why? Nso children are expected to control their emotions and wait from a very early age. Waiting is woven into their daily experience, so they’ve practiced it extensively.

Even more fascinating: Japanese children waited easily for food but struggled with wrapped gifts, while American children showed the opposite pattern. Japanese children regularly wait for everyone to be served before eating lunch at school. American children have extensive practice waiting until Christmas or party endings to open presents. (Make it fun with a scavenger hunt.) Each group excelled at waiting in contexts where they’d practiced most.

The researchers concluded that “kids have trouble waiting, but only in contexts where they’re not used to having to wait. If they’re used to waiting—like we are used to waiting for Christmas morning—they can totally do it.”

This has profound implications for today’s families. The shift toward digital gift culture and the two-day shipping generation means children may have fewer built-in opportunities to practice waiting than previous generations. Educational psychologist Michele Borba describes today’s children as part of a “now generation” where everything is instant, leading kids to expect instant gratification 24/7.

What’s Happening Inside Their Heads While They Wait

University of Notre Dame research captured something remarkable: what children actually say to themselves during challenging waiting tasks.

Graduate researcher Katie Edler explains:

“We call it private speech—while they were doing this task, some of them were expressing their frustration out loud… saying things like, ‘I can’t do this. This is so hard.’ But then we’re finding other kids that are strategizing, saying things like, ‘I have to keep trying. I can do this.'”

— Katie Edler, Graduate Researcher, University of Notre Dame

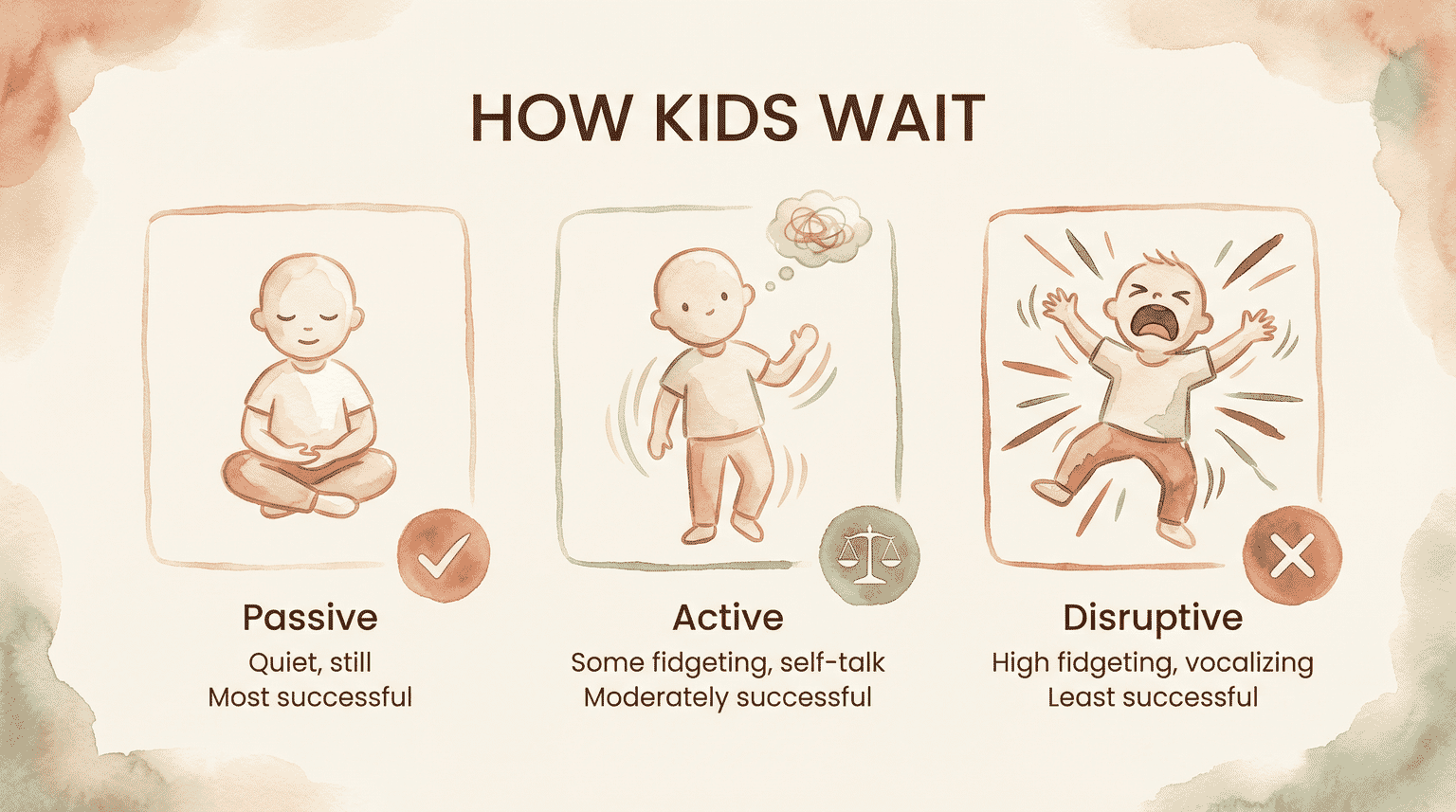

A 2023 study identified three distinct patterns in how 5-year-olds wait:

The children who succeeded weren’t necessarily the calmest—they were the ones whose strategies matched their arousal level. Children using motor strategies (fidgeting), verbal strategies (self-talk), or both resisted temptation longer than those using no strategies at all.

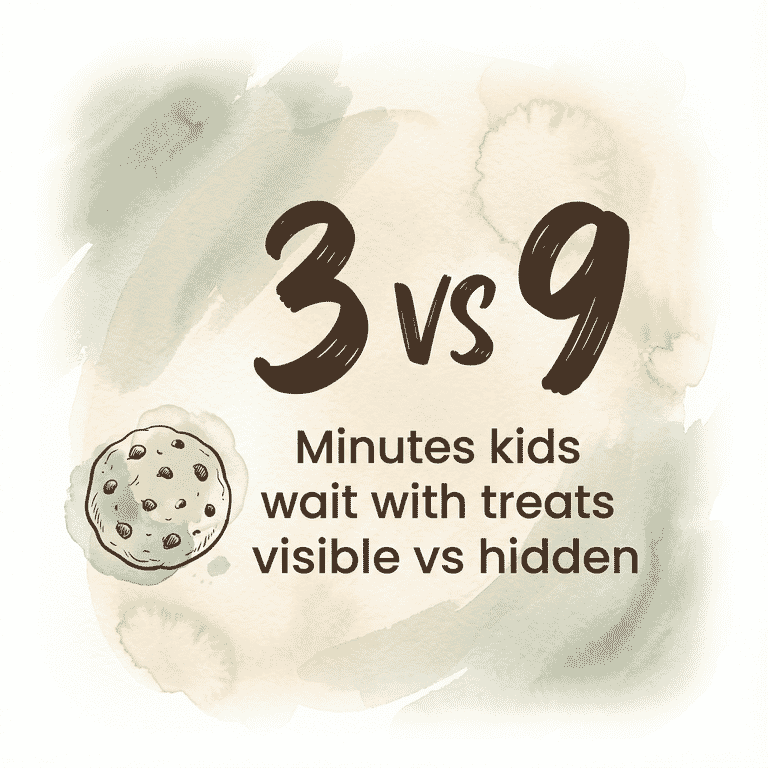

The original marshmallow research from the 1970s found that children who waited with treats visible only lasted about 3 minutes, while those with treats hidden managed almost 9 minutes.

“Out of sight, out of mind” genuinely helps—but only because it reduces the cognitive load of waiting.

Why Your Adult Brain Tricks You

Here’s something that surprised me: a 2022 study found that strategies helping adults wait actually make waiting harder for children.

When adults struggle with temptation, we’re often told to imagine how good the future reward will feel. This works for grown-ups. But for children under 12? Researchers found these future-thinking strategies are “too cognitively taxing” and may actually impair children’s ability to wait.

The study tested whether asking children ages 8-12 to imagine future rewards would help them delay gratification. Result: asking children to imagine anything while making choices significantly worsened their performance compared to no prompting at all.

I’ve definitely made this mistake. “Think about how great it’ll be when we get to the park!” doesn’t help my 6-year-old wait for the car ride—it might be making the waiting harder. Their working memory is already strained keeping the goal in mind; adding imagination tasks pushes them past capacity.

What This Means for Your Family

If your child struggles with waiting, I have genuinely good news from the research.

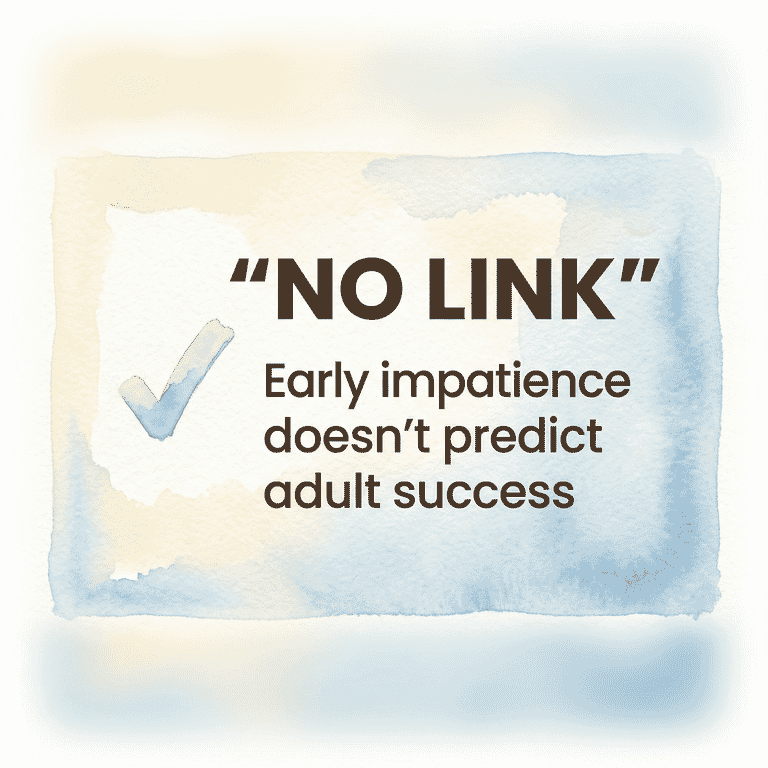

A 2020 study tracking the original marshmallow test children into their 40s found that children who quickly gave in showed “no statistically meaningful relationships” with adult outcomes including net worth, education, or health behaviors.

UCLA’s Daniel Benjamin summarized: “With the marshmallow waiting times, we found no statistically meaningful relationships with any of the outcomes that we studied.”

A major 2018 replication found that early patience differences disappeared after controlling for family environment and cognitive abilities. Environment shapes waiting ability far more than some innate “patience trait.”

This means:

- Your struggling waiter isn’t doomed. Early impatience doesn’t predict adult outcomes.

- Patience is genuinely learnable. Those Nso children prove that context and practice matter enormously.

- Developmental struggles are normal. Michele Borba reminds us that “young kids are supposed to be egocentric because their whole world is revolving around them.”

For practical strategies for teaching patience in our instant-gratification world, including specific techniques and parent scripts, I’ve put together a separate guide. Understanding the mechanisms is step one—but there’s plenty parents can do with this knowledge.

| Age | Realistic Waiting Ability | What Helps |

|---|---|---|

| 2-3 | Under 5 minutes is genuinely hard | Distraction; remove visible temptations |

| 4-5 | 5-10 minutes possible with support | Quality rewards work better than quantity |

| 5-6 | Significant capability increase | Simple self-talk strategies emerge |

| 6-7 | Can begin understanding patience conceptually | Can think about own behavior |

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does my child have no patience?

Children’s prefrontal cortex—the brain region controlling impulse control—doesn’t fully develop until the mid-20s. Your child isn’t choosing impatience; their brain literally lacks the infrastructure adults have for waiting. The years between toddlerhood and kindergarten are critical for developing these foundational skills.

At what age can children learn to wait?

Significant improvement begins around age 5, with children showing substantially better waiting ability than 3- and 4-year-olds. By age 6-7, children can begin understanding patience conceptually and thinking about their own behavior. But waiting skills develop gradually—there’s no magic switch.

Is it normal for toddlers to be impatient?

Absolutely. Educational psychologist Michele Borba explains that young kids are supposed to be egocentric because their whole world revolves around them. The overwhelming majority of preschool-aged children struggle with waiting tasks. Impatience at this age is developmentally appropriate, not a character flaw.

Why does time feel longer for kids?

Children lack the developed sense of temporal duration that adults have. Without accurate time perception, a “5-minute wait” provides no meaningful information—it simply feels endless. This isn’t stubbornness; it’s a fundamentally different experience of time passing.

Over to You

Does your child experience “later” as “forever”? I’m curious what’s helped them understand waiting—or whether you’ve just accepted that time works differently in kid-brain and adjusted your expectations accordingly.

Your waiting strategies might be exactly what another parent needs to hear.

References

- Why Children Can’t Just Wait – Cross-cultural research on patience development and context-dependence

- Patience is Learned – University of Michigan research on self-regulation development

- Comparison of Delay of Gratification Across Cultures – PLOS ONE study on age-related waiting thresholds

- Testing Emotional Resiliency – University of Notre Dame research on children’s private speech

- New Study Disavows Marshmallow Test’s Predictive Powers – UCLA research on long-term outcomes

Share Your Thoughts