Your daughter comes downstairs after thirty minutes of scrolling, slumps onto the couch, and sighs. “Everyone’s life is so much better than mine.” She’s 12. She got the phone six months ago. And somewhere between breakfast and now, she’s concluded that her ordinary Tuesday means she’s failing at life.

I’ve watched this scene unfold with my older kids more times than I’d like to admit. And my librarian brain couldn’t let it go without understanding why this keeps happening—and more importantly, what we can actually do about it.

Here’s what the research shows: this isn’t about your child being dramatic or ungrateful. It’s about how curated content works on developing brains, and why kids need specific tools to navigate it.

Key Takeaways

- Kids don’t automatically understand that Instagram shows highlight reels, not reality—hands-on demonstrations work better than lectures

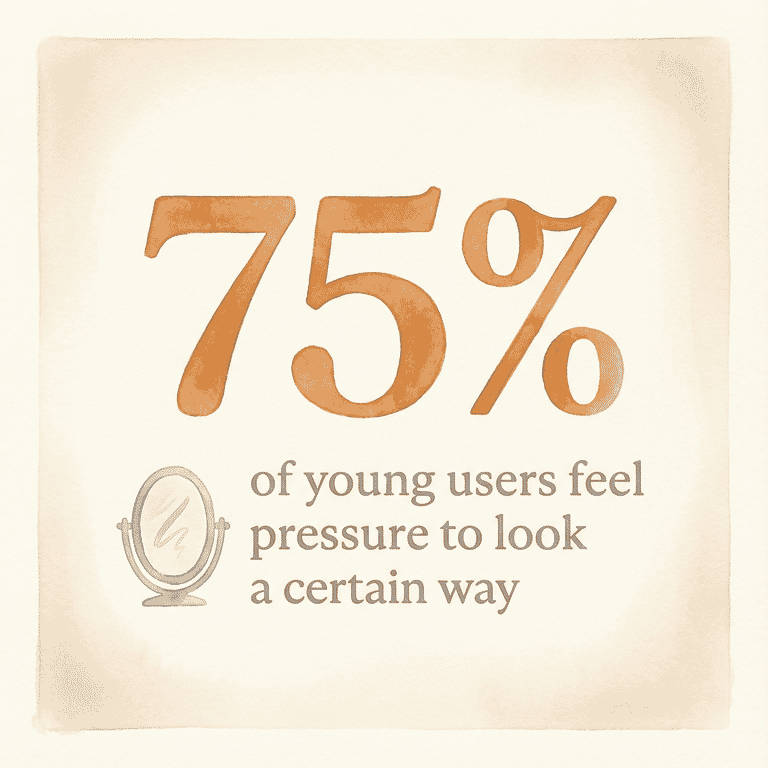

- 75% of young Instagram users feel pressure to look a certain way based on platform content—filter awareness activities help counter this

- Boredom—not genuine interest—drives most teen scrolling, so addressing boredom directly is more effective than restricting screen time

- When comparison statements emerge, validate feelings first, then gently probe—this builds media literacy over time

- These aren’t one-time conversations but ongoing dialogues that plant seeds for later self-awareness

What Your Child Is Actually Seeing (And Why It Matters)

Let’s start with what “curated content” actually means. Clinical therapist Alyssa Acosta of Loma Linda University puts it plainly: social media platforms are “flooded with meticulously curated profiles, showcasing seemingly perfect lives, flawless appearances, and ideal bodies.”

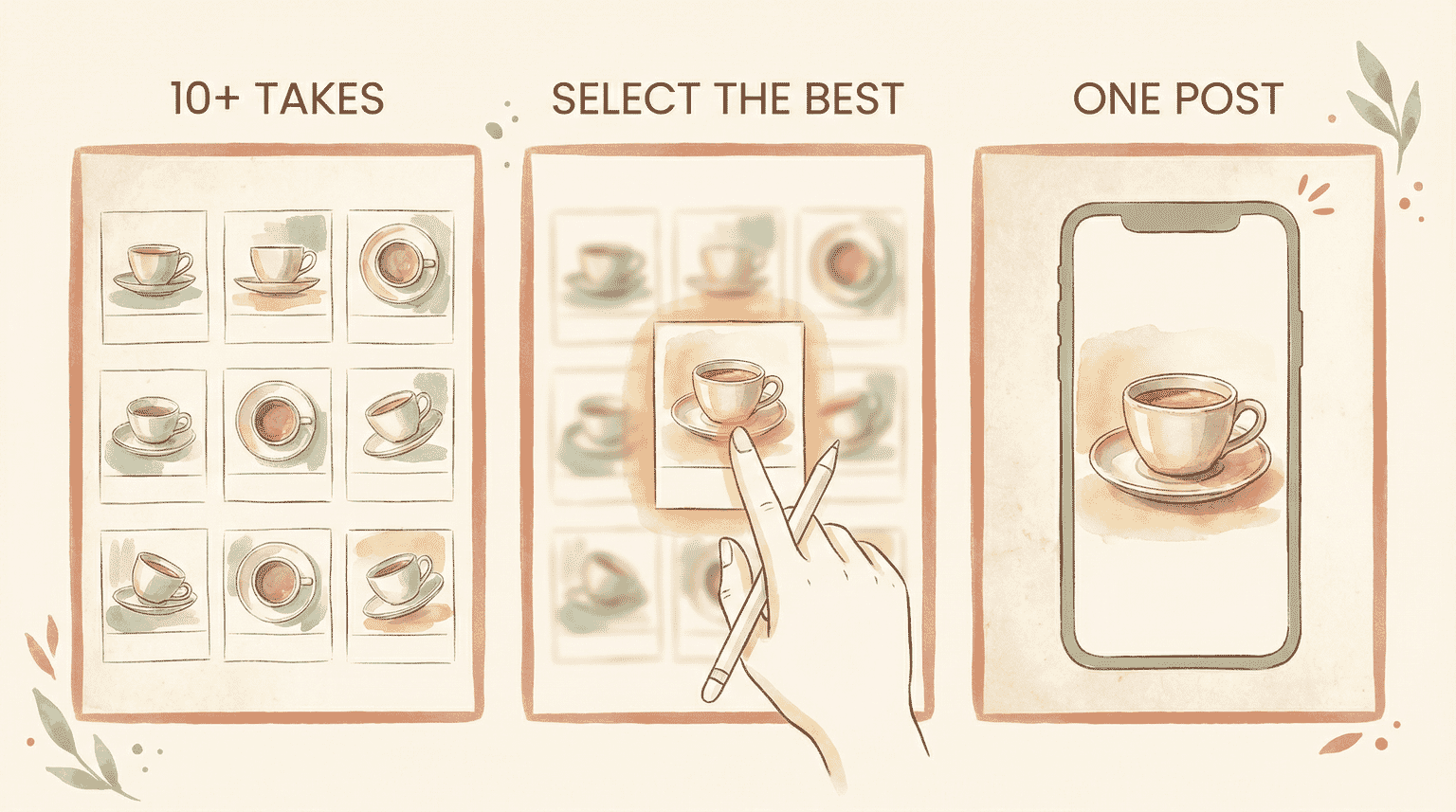

Translation: nobody posts their messy Monday. They post the one good photo from forty attempts. The vacation highlight, not the airport meltdown. The perfect outfit, not the three they rejected.

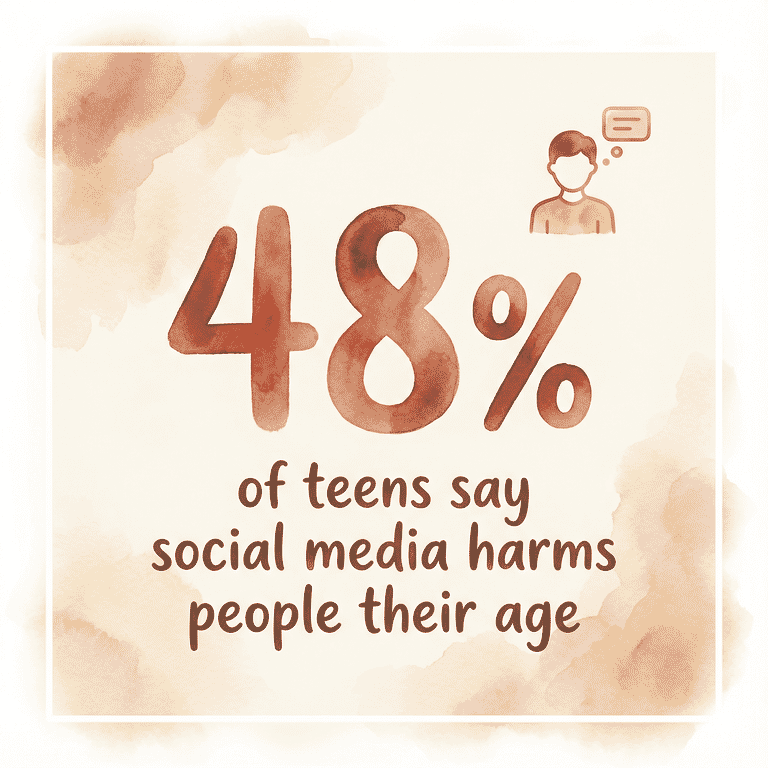

This matters because kids don’t automatically know this. A 2024 study from Penn State Extension found that 48% of teens believe social media negatively impacts people their age—yet they often can’t articulate how curation works. They’re aware something feels wrong, but lack the literacy to understand why.

Nearly half of teens recognize something’s off about social media—but they can’t explain why it feels that way.

That gap between sensing a problem and understanding it is exactly where media literacy comes in. Without the right tools, kids are left feeling bad without knowing why.

The mechanism is what researchers call “upward social comparison.” According to a 2024 NIH study tracking youth ages 10-14, social media comparisons are “more extremely upward” than comparisons made in real life. When your child compares herself to a classmate at school, she sees that classmate having bad days too. Online, she only sees highlight reels—and assumes they’re reality.

Here’s where understanding how digital culture shapes children’s expectations helps: this isn’t isolated to Instagram. It’s part of a broader pattern in how kids now experience curated versions of everything, from unboxing videos to influencer gift hauls.

Strategy #1: The Curation Demonstration

Before you explain curation, let your child experience it.

Here’s the activity: Pick something mundane—a cup of coffee, a stack of books, the dog. Have your child take 10-15 photos of it using different angles, lighting, and arrangements. Then ask: “Which one would you post?”

As they choose, ask:

- “What made you pick that one?”

- “What’s different about the others?”

- “If someone only saw this one photo, what would they think about this moment?”

Why this works: Rachel Rodgers, associate professor of applied psychology at Northeastern University, notes that “the level of literacy around the fact that these images are highly curated and often digitally altered is really variable.” This activity closes that gap by making the selection process visible—using your child’s own choices.

I’ve done this with my 10-year-old. She took 12 photos of her breakfast and spent three minutes picking the “best” one. Then it clicked: “Wait, so that’s what everyone else is doing too?”

What this teaches: Every post represents a choice. What appears effortless often took dozens of attempts to create.

Strategy #2: The “Behind the Grid” Conversation

Timing matters here. Have this conversation either before your child creates their own account, or when comparison statements emerge (“She’s so pretty,” “Their family is so much cooler”).

Conversation script:

Start with curiosity, not lecture: “I’m curious about something. When you scroll through Instagram, how do you decide what’s real versus what’s… performed?”

Then explore: “Think about your favorite account. What do you imagine happens right before they post? Right after?”

Go deeper: “Has there ever been a time when something looked amazing online, but when you experienced it yourself, it wasn’t quite the same?”

Adapt for different ages:

For younger kids (10-12), focus on the selection process: “If you could only show five photos from your whole week, which would you pick? What wouldn’t make the cut?”

For teens (13+), acknowledge complexity: “I’m not saying everything online is fake. But I am saying everyone—including adults—shows their best version. What do you think about that?”

The American Psychological Association emphasizes that ongoing discussions work better than single talks. This isn’t a one-time lecture; it’s a conversation you’ll return to.

Strategy #3: The Filter Reality Check

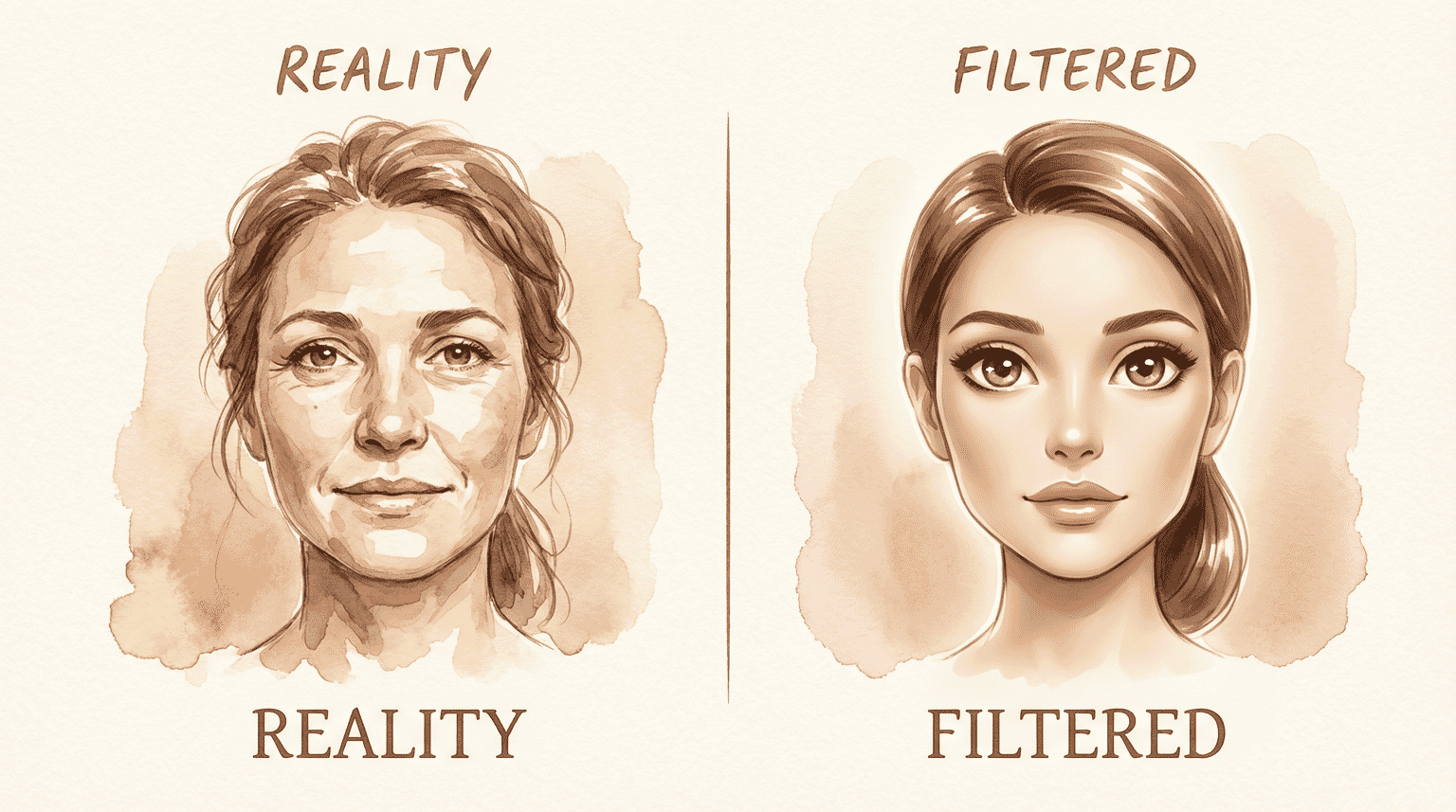

Filters are everywhere—and kids often don’t realize how dramatically they alter appearance.

The activity: Open Instagram together and explore filters. Take the same selfie with and without filters. Compare them side by side.

Discussion points:

- “What changed? Eyes bigger? Skin smoother? Jaw narrower?”

- “If you saw both versions without knowing they were the same person, would you guess they were?”

- “What happens if someone only ever posts the filtered version?”

Research from the NIH documents a phenomenon called “Snapchat dysmorphia”—people seeking cosmetic procedures to look like their filtered selfies. That’s the extreme end. But the everyday version is children believing filtered faces represent normal appearance.

The statistics are striking. That pressure eases when kids understand what they’re actually looking at.

When children learn to identify filter effects, they start questioning what they see rather than accepting it as reality. That skepticism is healthy.

What this teaches: The faces they see aren’t real faces. Altered appearances are normalized—but that doesn’t make them authentic.

Strategy #4: The Boredom Alternative Approach

Here’s something the research revealed that surprised me: University of Washington researchers tracked teens moment-by-moment and found that boredom—not genuine interest—is the primary driver of scrolling.

Kids open Instagram because they’re bored. Then they scroll through “a ton of junk,” as researcher Alexis Hiniker put it, seeking something stimulating. The most valued part of the platform? Direct messages—actual friend connection—not the endless feed.

The strategy: Instead of restricting screen time (which treats the symptom), address boredom directly.

Work with your child to create a “boredom alternatives” list. Keep it accessible wherever they usually grab their phone:

- Sketch for 5 minutes

- Text a friend to actually hang out

- Step outside—literally just stand on the porch

- Start a puzzle or project left unfinished

This works because it reframes the problem. Your child isn’t scrolling because they love Instagram; they’re scrolling because nothing else is competing for their attention in that moment.

Hiniker acknowledged what many parents fear to admit: “That value is definitely there, but it’s really buried in gimmicks, attention-grabbing features, content that’s sometimes upsetting or frustrating, and a ton of junk.”

What this teaches: Scrolling is often a response to boredom, not a genuine desire for content. Recognizing that pattern gives kids power over it.

Strategy #5: The Comparison Interrupt

When your child says “Her life is so much better” or “I wish I looked like that,” you have a brief window to respond helpfully.

In the moment:

Validate first: “It sounds like seeing that made you feel something. Tell me more about what you noticed.”

Then gently probe: “If you were posting, what would you choose to show? What would you leave out?”

Normalize the gap: “That feeling of comparing yourself—pretty much everyone gets it. Even adults. It doesn’t mean something’s wrong with you.”

Within 24 hours, follow up:

“I’ve been thinking about what you said yesterday. Can we talk about it more?”

Then explore: What specifically triggered the comparison? Was it appearance, lifestyle, friendships, or something else? Does this happen often, or was it unusual?

A 2024 study found that the vast majority of young users experience FOMO—that fear of missing out that social media amplifies.

Your child’s response is normal. The goal isn’t eliminating comparison (impossible) but developing awareness of it.

This applies beyond social media, too. The same comparison dynamics appear when kids notice what friends receive as gifts or experience on vacations—understanding the root mechanism helps with all forms of comparison to what peers have or experience.

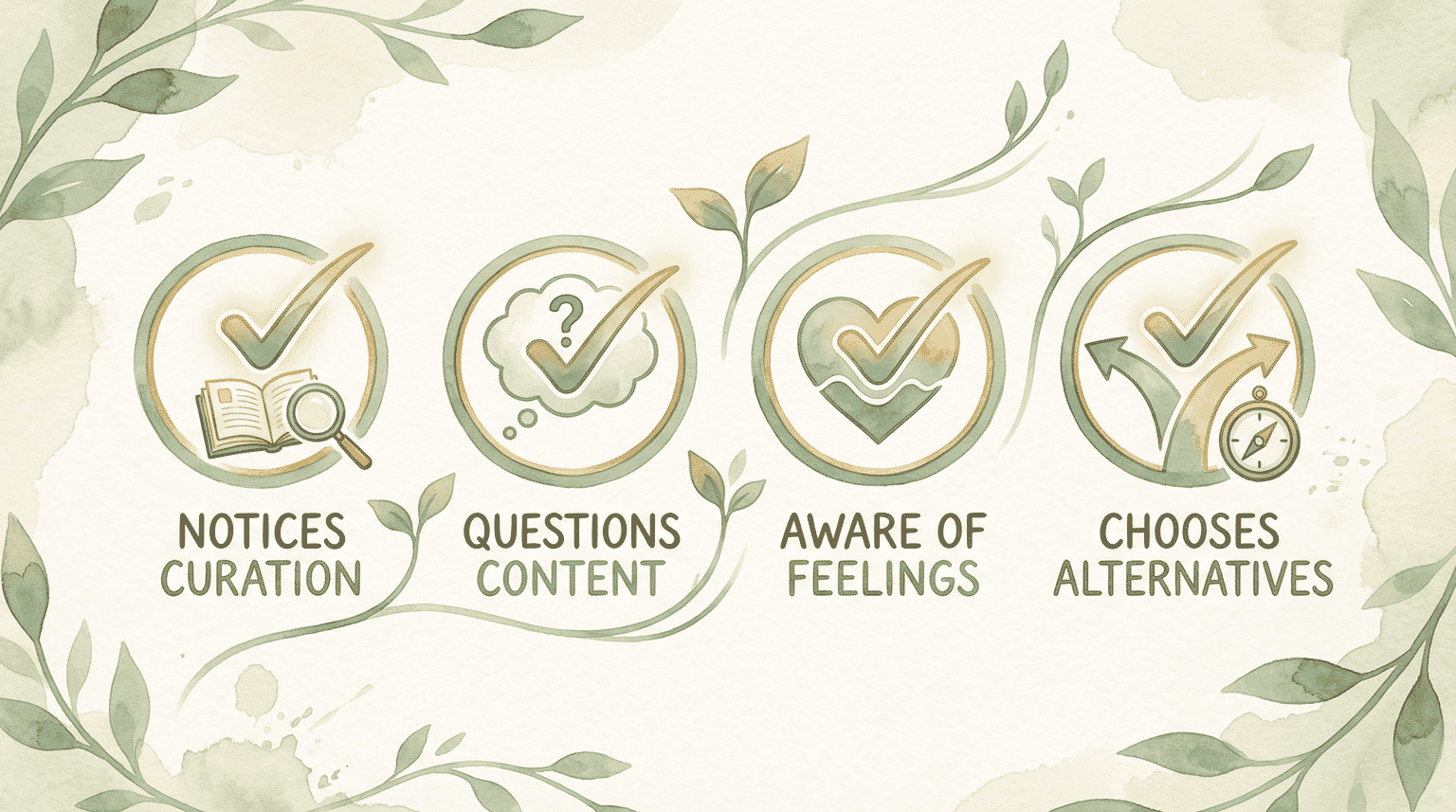

Recognizing When Strategies Are Working

Signs your child is developing media literacy:

- They notice curation themselves (“That’s probably not what it actually looked like”)

- They question before comparing (“I wonder how many takes that took”)

- They express awareness of how scrolling makes them feel

- They occasionally choose alternative activities over the phone

When to be concerned:

The APA identifies warning signs including: choosing social media over in-person interaction consistently, sleep disruption, continued use despite expressed desire to stop, and deceptive behavior to access platforms.

Research from NIH indicates approximately 24% of adolescents meet criteria for social media addiction. If your child spends more than three hours daily on platforms and shows signs of distress, that warrants attention.

Remember: some comparison is developmentally normal. Adolescents are supposed to be figuring out who they are relative to others. The question is whether social media is distorting that natural process.

The Ongoing Conversation Framework

The responsibility for navigating curated content shouldn’t fall on kids alone.

“It is not and should not be the sole responsibility of teens to make their experiences better, to navigate these algorithms without knowing how they work, exactly.”

— Rotem Landesman, Researcher, University of Washington

This isn’t about perfecting a single conversation. It’s about creating many small moments where media literacy naturally emerges.

Weekly check-in questions:

- “What’s been the best thing you’ve seen online this week? The worst?”

- “Notice anything that seemed too good to be true?”

- “How does scrolling usually leave you feeling?”

Parent modeling: Your own relationship with curated content matters. Narrate your own awareness: “I just saw someone’s vacation photos and felt a little jealous. Then I remembered she probably didn’t post the delayed flight.”

I’ve done this imperfectly for years across 8 kids. What I’ve learned: the 17-year-old who rolled her eyes at these conversations at 13 now catches herself mid-scroll and puts the phone down. The seeds take time. Plant them anyway.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is Instagram bad for kids’ self-esteem?

Instagram can harm self-esteem through constant exposure to curated, idealized content that triggers unfair comparisons. The visual nature of the platform—where users share only their best moments—creates a distorted view of reality that developing minds struggle to evaluate critically. Research shows 75% of young users feel pressure to look or achieve a certain way based on what they see.

How do I talk to my child about fake Instagram posts?

Start with a hands-on demonstration rather than a lecture. Have your child take 10 photos of something simple, then choose “the best one” together. This reveals the selection process behind every post. Follow with open questions: “If you only saw this one photo, what would you think about this moment?” The American Psychological Association recommends ongoing discussions rather than a single talk.

What is curated content on social media?

Curated content is material carefully selected, edited, and presented to show only the most favorable version of reality. On Instagram, this means users choose their best photos, apply filters, write captions that emphasize positives, and delete posts that don’t perform well. Clinical therapist Alyssa Acosta describes platforms as “flooded with meticulously curated profiles, showcasing seemingly perfect lives.”

How do filters affect body image?

Filters distort children’s perception of normal appearance by normalizing altered features. Researchers have documented “Snapchat dysmorphia”—where individuals seek cosmetic procedures to resemble their filtered selfies. Studies show 32% of teen girls say Instagram makes existing body image issues worse, and 75% of young users feel pressure to look a certain way based on platform content.

Join the Conversation

Have you talked to your kid about Instagram’s highlight-reel problem? I’d love to hear whether they believed you—and whether any of these strategies have actually shifted how they feel after scrolling.

Your stories help other parents know they’re not navigating this alone.

References

- American Psychological Association – Parent guidance on adolescent brain development and social media vulnerability

- Loma Linda University Behavioral Health – Clinical perspective on curated content and self-image

- Penn State Extension – 2025 survey findings on teen attitudes toward social media

- National Institutes of Health (PMC) – Research on social comparison and youth well-being

- Northeastern University – Expert analysis on media literacy gaps in adolescents

- University of Washington – Research on boredom as primary driver of scrolling behavior

- American Journal of Applied Psychology – Statistics on FOMO and self-comparison among young Instagram users

- National Institutes of Health (PMC) – Research on social media addiction criteria and mental health correlations

Share Your Thoughts