My 6-year-old watched a toy unboxing video last week. Just one. Within 48 hours, she had asked for that exact toy fourteen times—always using the YouTuber’s name like she was referencing a trusted friend. “But Lily said it’s the BEST ONE,” she insisted.

Here’s the thing: Lily earned $26 million last year. My daughter has no idea.

Welcome to the world of influencer toy reviews—where children watch other children play with toys—never realizing they’re watching some of the most sophisticated advertising ever created. And as someone whose librarian brain couldn’t let this phenomenon go without investigation, I’ve spent months digging into what’s actually happening when our kids press play.

What I found is a multi-billion dollar industry built on children’s trust. Let me show you what’s really going on.

Key Takeaways

- Children under 12 cannot effectively defend against influencer advertising—even when they know ads exist

- Top child influencers earn $15,000-$500,000 per sponsored post, with one generating $26 million in ad revenue by age 9

- Kids nag parents more after watching unboxing videos than traditional TV commercials due to parasocial “friendship” bonds

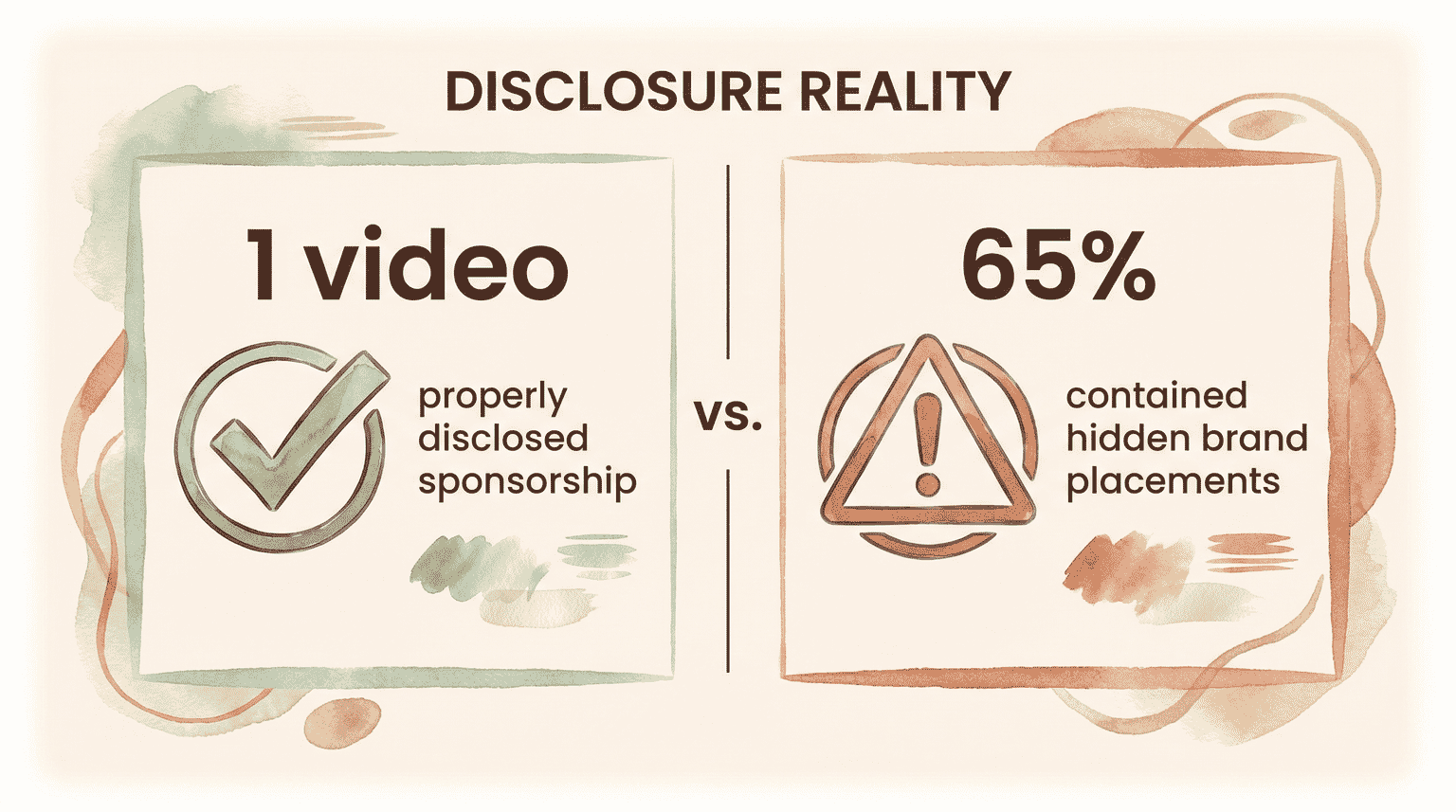

- Only 1 video out of hundreds studied actually disclosed brand sponsorship—regulations aren’t protecting your kids—teach them to spot sponsored content

- Co-viewing and age-appropriate conversations about persuasive intent are your best defense

The Business Behind “Just Playing”

Here’s the financial reality most parents never see: A 2020 analysis from William & Mary Business Law Review found that child influencers with 1.5 million followers can earn $15,000 per sponsored post. Top creators command $100,000 to $500,000 for a single piece of content.

The money is staggering. Ryan’s World—perhaps the most famous kid toy reviewer—generated an estimated $26 million in advertising revenue in 2019 alone, according to research from UNLV. By age 9, Ryan was the highest-paid YouTuber, with 95% of that income coming from advertisements rather than content itself.

This isn’t a few kids playing with toys who happened to go viral. It’s a sophisticated industry where sponsors include Nickelodeon, Walmart, Netflix, and Hasbro—brands that know exactly what they’re buying.

What are they purchasing? Access to your child through a “friend.”

Understanding this business model is part of a larger shift in how digital platforms are reshaping gift culture—one that puts children at the center of marketing strategies in unprecedented ways.

Why Your Child Can’t Tell It’s an Ad

Here’s what the research actually shows about children’s ability to recognize advertising:

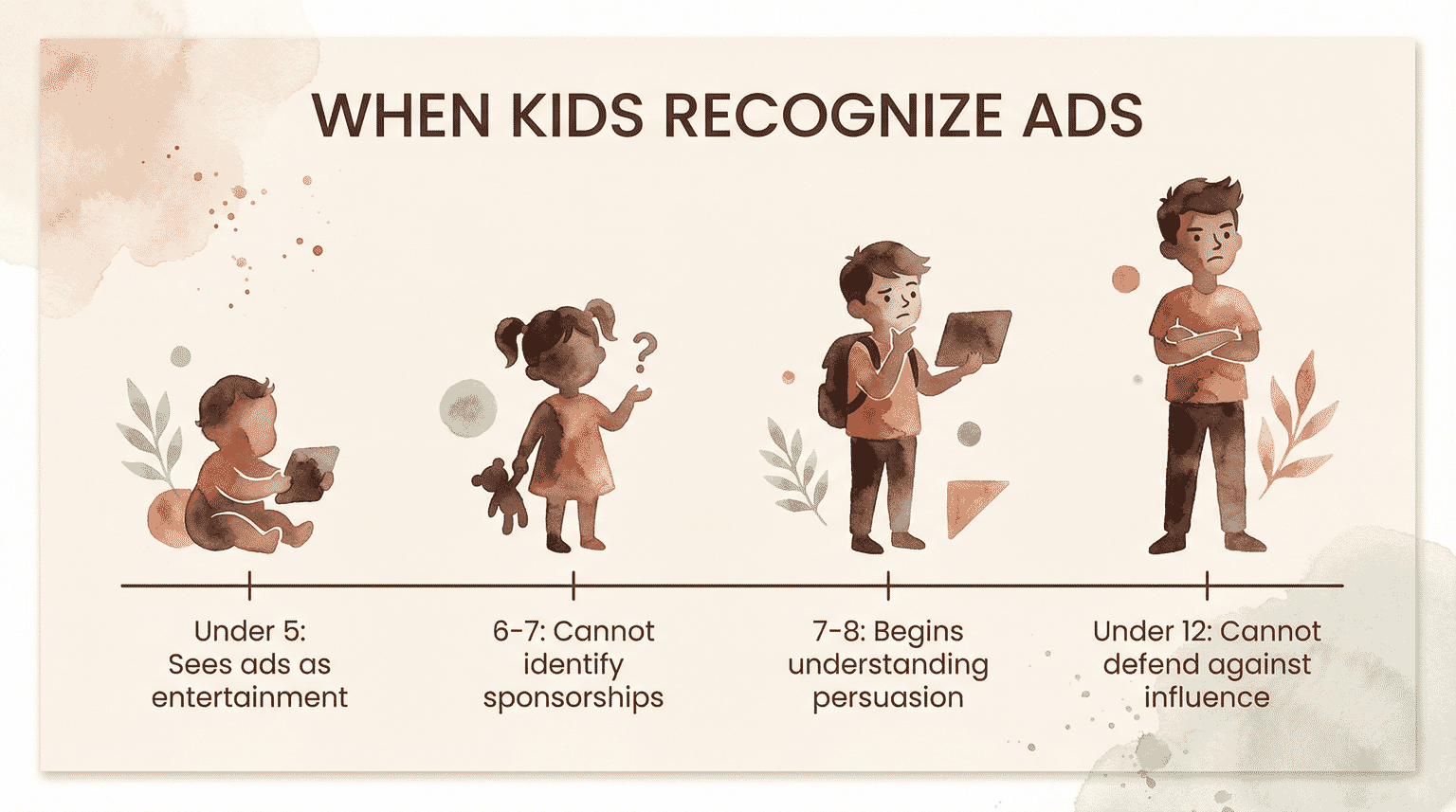

Children under 5 view advertising as entertainment. Not “sometimes confuse” it—they literally perceive commercials and sponsored content as another form of fun content to watch.

Ages 6-7 have the greatest difficulty identifying sponsorships and product placement, according to a 2023 study of 263 children.

Ages 7-8 begin understanding that advertising has persuasive intent—that someone is trying to convince them of something.

Children under 12 cannot effectively defend against advertising influence, even when they recognize it exists.

Even ages 9-16 lack awareness of hidden advertising in influencer videos, per research from the Australasian Marketing Journal.

Here’s why influencer content is worse than traditional commercials: the format itself is designed to bypass developing critical thinking. (Try these 3 questions to build it.). As Truth in Advertising stated bluntly in their 2019 FTC complaint: “Organic content, sponsored content—it’s all the same to preschoolers.”

My toddler can’t read the tiny “#ad” disclaimer. My 6-year-old doesn’t know what “sponsored” means. Even my 10-year-old, who understands commercials on TV, doesn’t connect that his favorite YouTuber is being paid to hold up that toy.

The Manufactured Best Friend

The real mechanism at work isn’t just advertising—it’s something psychologists call parasocial relationships.

These are one-sided emotional bonds where children invest genuine emotional energy believing influencers are their friends, while the influencer remains completely unaware of their existence. Children and Screens research explains that by sharing their “authentic” selves—bedroom tours, family dinners, silly moments—influencers create perceived intimacy that traditional advertising never could.

“The problem with these videos is that they send a strong message of consumerism. The central theme is that buying the promoted toy can bring unlimited happiness. Unfortunately, a child is only satisfied with the toy until they are bored and start looking for the next item to fill this void.”

— Dr. Kelli S. Burns, University of South Florida

I’ve watched this happen with my own kids. They don’t just want the toy—they want to recreate the joy they saw on screen. When the toy arrives and the experience doesn’t match the curated enthusiasm of a professionally produced video, they’re confused and disappointed. Then they’re ready for the next one.

This is why children are more likely to nag parents for products after watching unboxing videos than after traditional TV commercials. The trust transfer is profound.

When a “friend” recommends something, it hits differently than a stranger in a commercial break.

The Disclosure Illusion

Surely regulations protect our kids, right? Not quite.

The FTC requires influencers to disclose sponsored content. But a UConn Rudd Center study analyzing child-influencer videos found something remarkable: just one video out of hundreds analyzed actually disclosed a food-brand sponsorship. One.

The same study found 65% of child-influencer videos contained food brand appearances, averaging nearly 4 brands per video. Total views for the analyzed channels exceeded 155 billion.

Even when disclosures exist, they’re meaningless to the most vulnerable viewers:

- Preschoolers can’t read “#ad” or “#sponsored”

- Disclosures often flash in the first seconds before children are paying attention

- Studies show disclosures are ineffective at reducing marketing impact on children ages 9-14—and may actually increase positive attitudes about products

The Children’s Advertising Review Unit investigated Ryan ToysReview back in 2017 and concluded the unboxing videos “amounted to advertisements not properly disclosed.” Yet here we are, years later, with the problem exponentially larger.

For parents wanting to understand the broader landscape of hidden advertising on YouTube, this disclosure gap is just the beginning.

The Algorithm Trap

Even if you’ve never actively searched for toy reviews, your child has likely been served them.

YouTube’s algorithm doesn’t just suggest content—it creates exposure spirals. Pew Research found that the platform consistently recommended children’s content to viewers regardless of what they started watching. Of 346,086 unique videos analyzed, the single most recommended video was an animated children’s video.

“Do your kid—and yourself—a favor and don’t let them watch unboxing videos, especially since if your child watches a couple, YouTube will be relentless in recommending more.”

— Josh Golin, Executive Director of Fairplay

I’ve tested this myself. A few toy videos in my 4-year-old’s viewing history transformed her entire recommendations feed into an endless scroll of unboxing content. It took weeks of active management to reset.

Pester Power Amplified

“Pester power” is the academic term for what every parent knows intimately: children’s ability to influence—sometimes relentlessly—parental purchasing decisions.

BYU researcher Dr. Jason Freeman explains that pester power results directly from watching unboxing videos because “kids know the exact type of toy brand to look for once they enter a store.” The specificity is the problem. It’s not “I want a doll”—it’s “I want the LOL Surprise OMG Series 4 Lights Groovy Babe Fashion Doll.”

Children also don’t realize toy influencers receive products for free, leaving them wondering why their parents can’t provide the same abundance. In my house, this sounds like: “But they have so many toys!”

This is where these desires end up—kids’ wishlist apps that capture every influencer-sparked want with one-click efficiency.

What Actually Works

The research on countering influencer marketing points to one powerful tool: engaged parenting.

“Since children don’t have the ability to sufficiently understand the underlying persuasive intent of unboxing videos, it’s up to parents to internalize, understand, and then educate themselves. When parents critically engage with this content… they are able to teach their children how the content might shape their child’s attitudes and behavior.”

— Dr. Jason Freeman, BYU

Detection skills to develop:

- Watch for disclosure statements in the first seconds or description (#ad, #sponsored, #partner)

- Notice multiple products from the same brand in one video

- Listen for calls to purchase or links to buy

- Pay attention to unusually enthusiastic reactions to product features

But here’s the catch: Freeman’s research found parents struggle to identify paid promotions without explicit disclosure. Assume commercial intent unless proven otherwise.

Conversation starters by age:

For younger children (under 8): “Who do you think gave them that toy? How do you think they got so many?”

For older children: “Why do you think they made this video? How do they make money?”

For tweens: “If a company paid you to talk about their toy, how would you act?”

What research supports for boundaries:

- Young children may benefit from restricted media time around this content

- Older children benefit from active parental mediation: co-viewing, two-way dialogue about what’s happening

- Dr. Tim Kasser’s research suggests modeling skepticism actually works—parental mockery of advertisements has been shown to decrease children’s materialistic desires

Teaching Skepticism Without Cynicism

My goal isn’t raising kids who trust nothing. It’s raising kids who ask questions.

The researchers behind the study of children negotiating kidfluencer content recommend what French psychologist Serge Tisseron calls the “3-6-9-12 rule”—graduated screen time guidance that recognizes media literacy develops over time, not through single conversations.

Questions that build evaluation skills:

“What do you think would happen if the toy didn’t work like that?” “Do they ever show toys they don’t like?” “How would you feel if you got that toy and it wasn’t as fun?”

I’ve watched my older kids develop this radar over time. My 15-year-old now spots sponsored content instantly and finds it “cringe.” My 12-year-old is learning. My 6-year-old isn’t there yet—and that’s developmentally appropriate.

The goal is progress, not perfection.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are toy review videos bad for kids?

Toy review videos aren’t inherently harmful, but research shows they trigger more purchase requests than traditional commercials. The central problem: children under 12 cannot effectively distinguish sponsored content from genuine recommendations, making them uniquely vulnerable to embedded advertising they perceive as a trusted friend’s advice.

How do I know if a toy video is an ad?

Look for disclosure statements (#ad, #sponsored, #partner) in the first few seconds or video description. Watch for multiple featured products from the same brand, calls to purchase, or links to buy. However, research found just one video in hundreds disclosed brand sponsorship—assume commercial intent unless proven otherwise.

Why does my child want every toy from YouTube?

Children develop parasocial relationships—one-sided emotional bonds—with influencers they watch repeatedly. Unlike TV commercials featuring strangers, these videos create the illusion of friendship, making recommendations feel like trusted advice. YouTube’s algorithm then reinforces this by relentlessly recommending similar content.

At what age can children recognize advertising in YouTube videos?

Children under age 5 view advertising as entertainment. Around ages 7-8, children begin understanding persuasive intent. However, research shows children under 12 cannot effectively defend against advertising influence, and even children ages 9-16 struggle to identify hidden advertising in influencer videos.

What About You?

Does your kid reference influencers like trusted friends? I’d love to hear how you’ve handled the “but SHE said it’s amazing” conversations—and whether any approach has helped build skepticism without crushing their excitement.

These conversations are tricky—sharing yours helps other parents navigate them too.

References

- Play Is a Child’s Work (on Instagram) – M/C Journal research on children’s media consumption and influencer marketing

- Safeguarding ‘Child Influencers’ Through Expanded Coogan Law – William & Mary Business Law Review analysis of child influencer financial exploitation

- Branding Kidfluencers – UNLV Gaming Law Journal research on YouTube advertising and child influencers

- The Influencer Impact: A Parent’s Guide – Children and Screens Institute guidance on parasocial relationships and parenting strategies

- Prevalence of Food and Beverage Brands in Child-Influencer YouTube Videos – UConn Rudd Center study on disclosure failures

- Unboxing Videos on YouTube – BYU research on parent detection skills and pester power

- A Paradox Theory of Social Media Consumption and Child Well-being – Australasian Marketing Journal research on developmental vulnerability timeline

- Children Negotiating Meanings in Kidfluencers’ Channels – Journal of Media Literacy Education study on age-specific comprehension gaps

Share Your Thoughts