Your child knows that video is sponsored. They can see the #ad in the caption. And they’re still asking for the product five minutes later.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth my librarian brain couldn’t let go: a 2022 systematic review of 38 studies found that only 40% of 11-12 year olds understand persuasive intent in advertising. But the really surprising finding? Understanding doesn’t protect them. Children who recognized sponsored content were still influenced by it.

So explaining “this is an ad” isn’t enough. What actually works is asking questions together.

Key Takeaways

- Recognizing ads doesn’t protect kids from being influenced—only 40% of 11-12 year olds even understand persuasive intent

- Three specific questions help children evaluate influencer content, not just recognize it’s sponsored

- Kids trust influencers like real friends, so lectures backfire—questions let them discover the gaps themselves

- Parents who discuss and critique media together raise kids with stronger critical thinking and less brand interaction

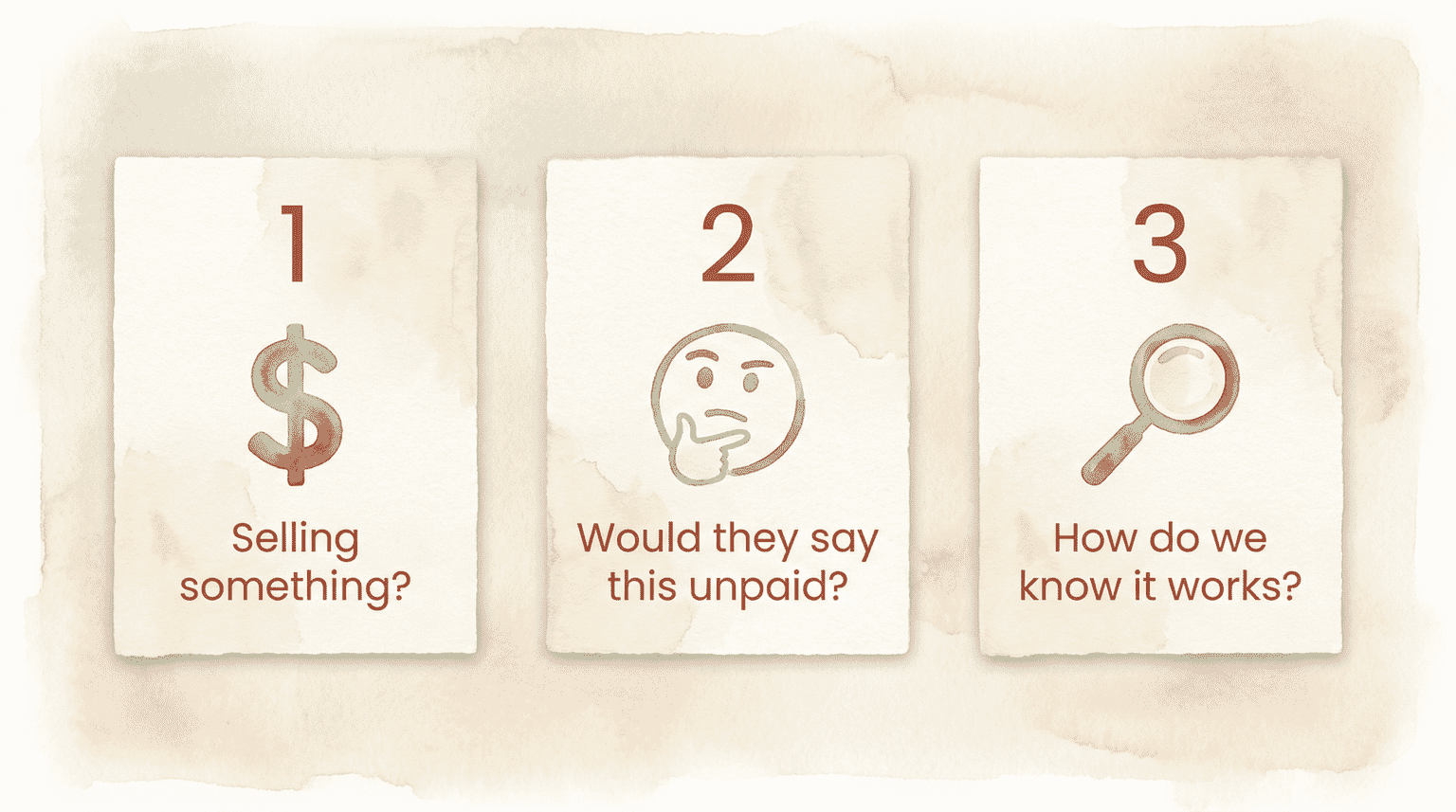

Three Questions to Ask While Watching

1. “Is this person trying to sell something?”

This builds basic recognition—the foundation. Most kids can get here with practice.

2. “Would they say this if they weren’t getting paid?”

This is where critical thinking actually starts. Research from Nature confirms that “merely recognizing the advertising intent of a message does not automatically translate into the ability to question or interpret the received content.” This question forces evaluation of motivation, not just recognition of disclosure.

3. “How do we know this actually works?”

Now you’re teaching evidence evaluation. One teen in that same study noticed an influencer using a beauty filter while promoting makeup and asked: “If the makeup was truly good, why did she need to rely on a filter?” That’s the thinking we’re building toward.

The beauty of these questions is they don’t require you to be the bad guy. You’re not saying “that influencer is lying.” You’re inviting curiosity.

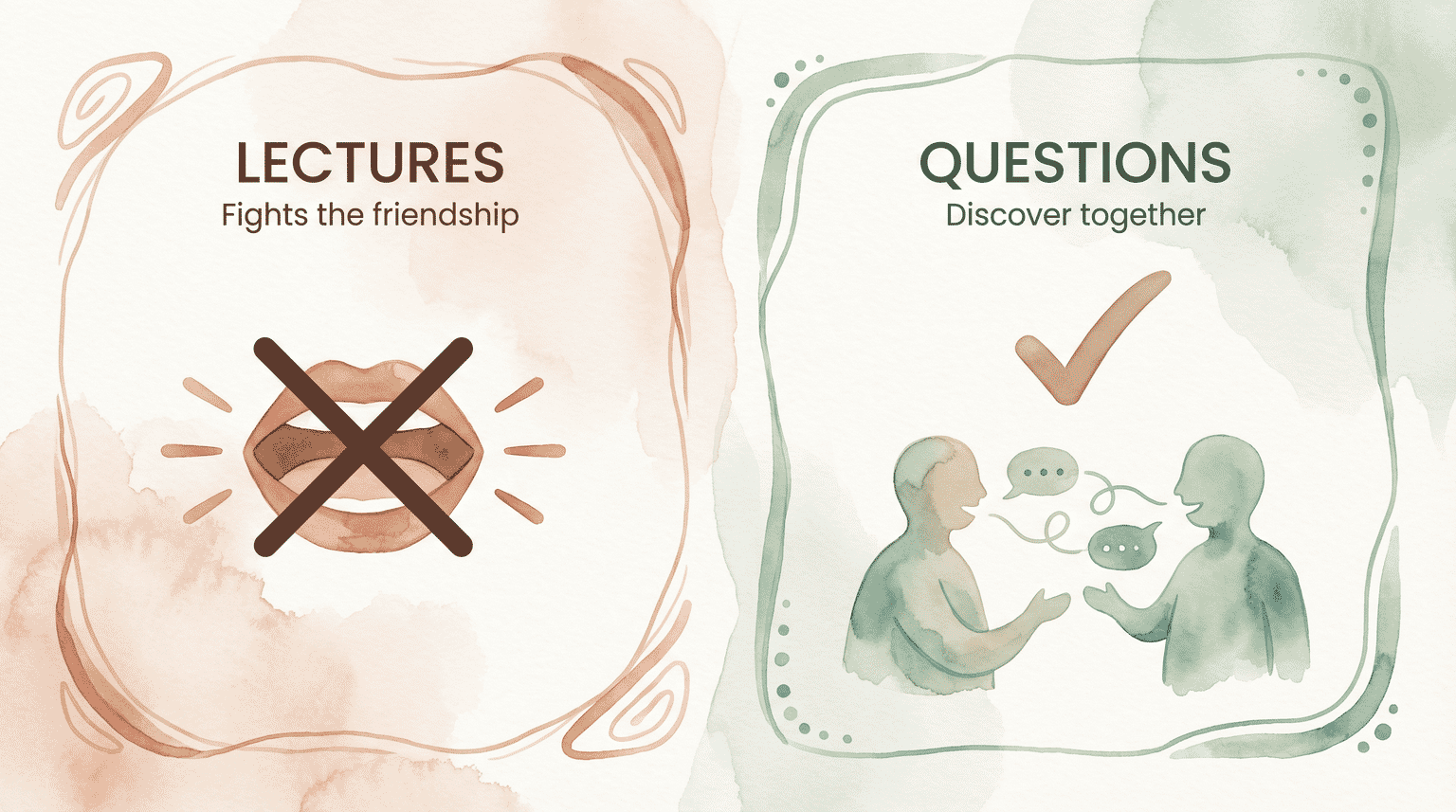

Why Questions Work Better Than Lectures

Here’s what’s happening in your child’s brain: parasocial relationship research shows that followers develop perceived friendships with influencers, leading to purchases “without reservation” because their favorite creator promotes products. Your child isn’t being gullible—they trust influencers like they’d trust a friend.

This is why telling them “don’t trust influencers” fights that friendship directly. You’re essentially asking your child to doubt someone they care about.

Asking questions together lets them discover the gaps themselves. The realization comes from them, not from you.

Studies show that parents who discuss and critique media messages have children with stronger critical thinking skills and less brand interaction—the same kind of developmental science that shapes how kids process gifts overall.

The research is clear: conversation beats correction. When you watch together and wonder aloud, you’re modeling the exact skepticism you want them to develop.

Over time, they’ll start asking these questions without you prompting them. That’s the goal.

Want to understand more about why children feel like influencers are their friends? The psychology explains a lot about how digital culture shapes gift expectations.

The takeaway: Don’t just explain that content is sponsored. Watch together, ask these three questions, and let your child practice evaluating—not just recognizing—what they’re seeing.

I’m Curious

Have these questions helped your kid think more critically about influencer content? I’d love to hear which ones landed—and whether the conversations have gotten easier or harder over time.

Your wins and fails help other families navigate influencer culture too.

References

- Advertising and Young People’s Critical Reasoning Abilities – Systematic review of 38 studies on advertising literacy development

- Do I Question What Influencers Sell Me? – Research on adolescent critical thinking and influencer content

- Rise of Social Media Influencers as a New Marketing Channel – Parasocial relationship research and consumer behavior

Share Your Thoughts