You’ve watched it happen: the gift is opened, the obligatory “thank you” is mumbled, and your child’s eyes are already scanning for the next package. Or worse—they actually complain. You feel that familiar mix of embarrassment and frustration, wondering where you went wrong.

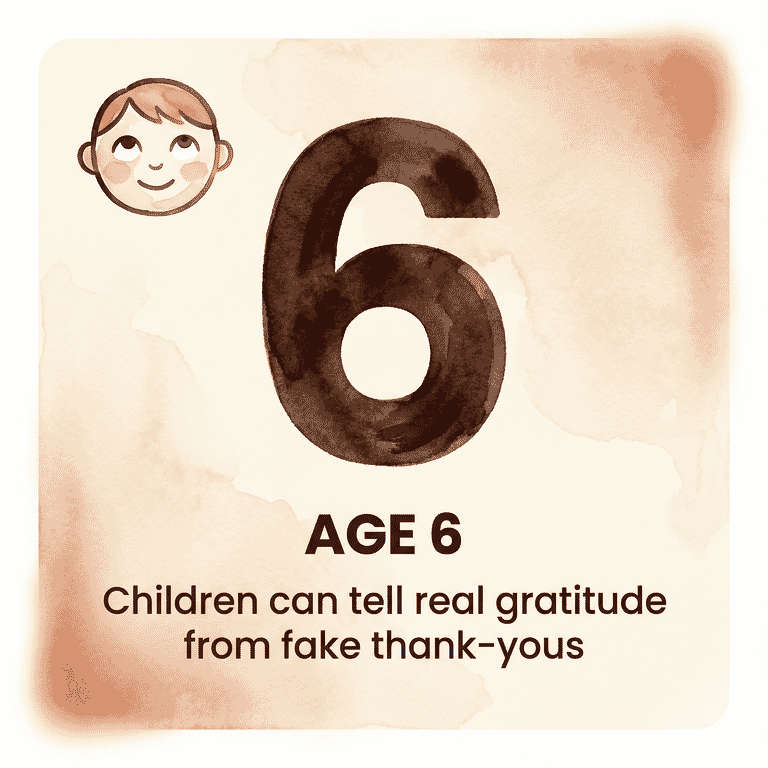

Here’s the thing: “Say thank you” doesn’t teach gratitude. It teaches compliance. And deep down, our kids know the difference. Research shows that even six-year-olds can distinguish between someone who said thank you and someone who actually meant it.

My librarian brain couldn’t let this go without digging into the research. What I found changed how I approach gratitude with all eight of my kids: a framework that breaks gratitude into four teachable components. Not vague advice about “modeling appreciation”—but specific places where parents can actually intervene when gratitude isn’t clicking.

According to St. Louis Children’s Hospital research, gratitude does more than make kids polite. It increases empathy, boosts self-esteem by reducing social comparison, improves emotional regulation, and reduces anxiety by shifting focus from problems to positives. Those benefits are worth pursuing—but first, we need to understand what we’re actually teaching.

Key Takeaways

- Gratitude has four teachable components: Notice, Think, Feel, and Do—and “say thank you” only addresses the last one

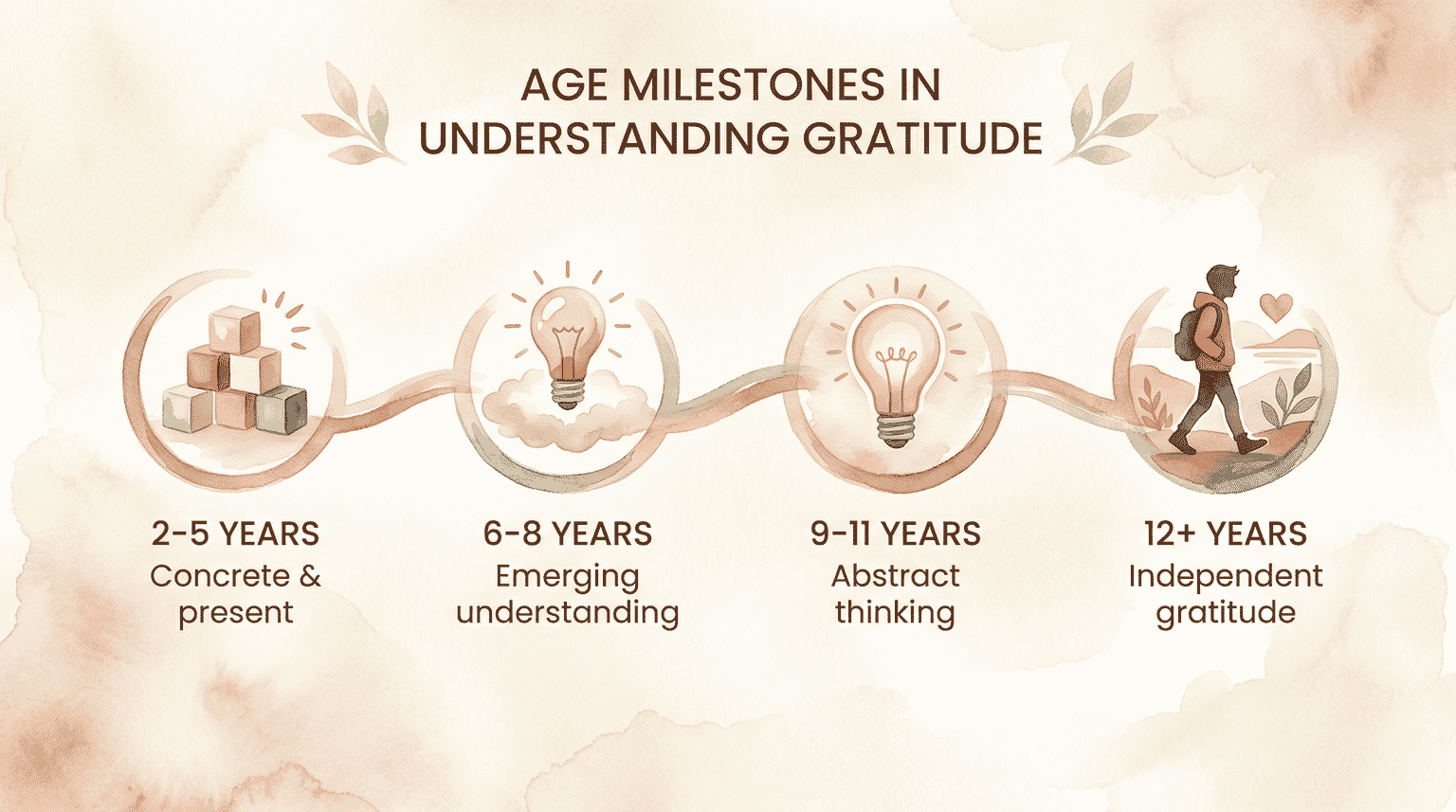

- Children commonly develop full gratitude capacity between ages 7 and 10. (When do kids understand gift giving?), so adjust expectations by age

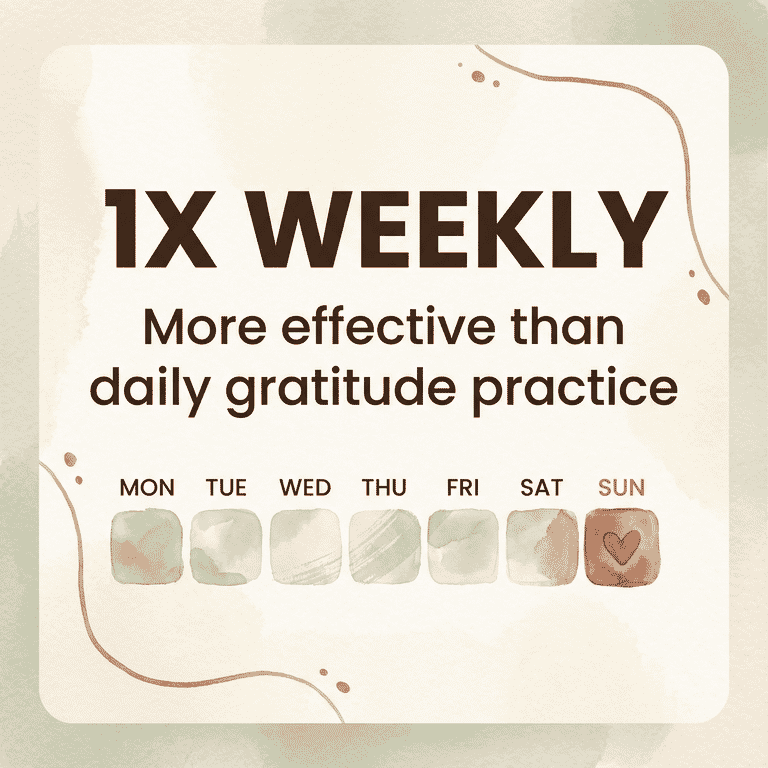

- Weekly gratitude practice is more effective than daily—overdoing it can backfire

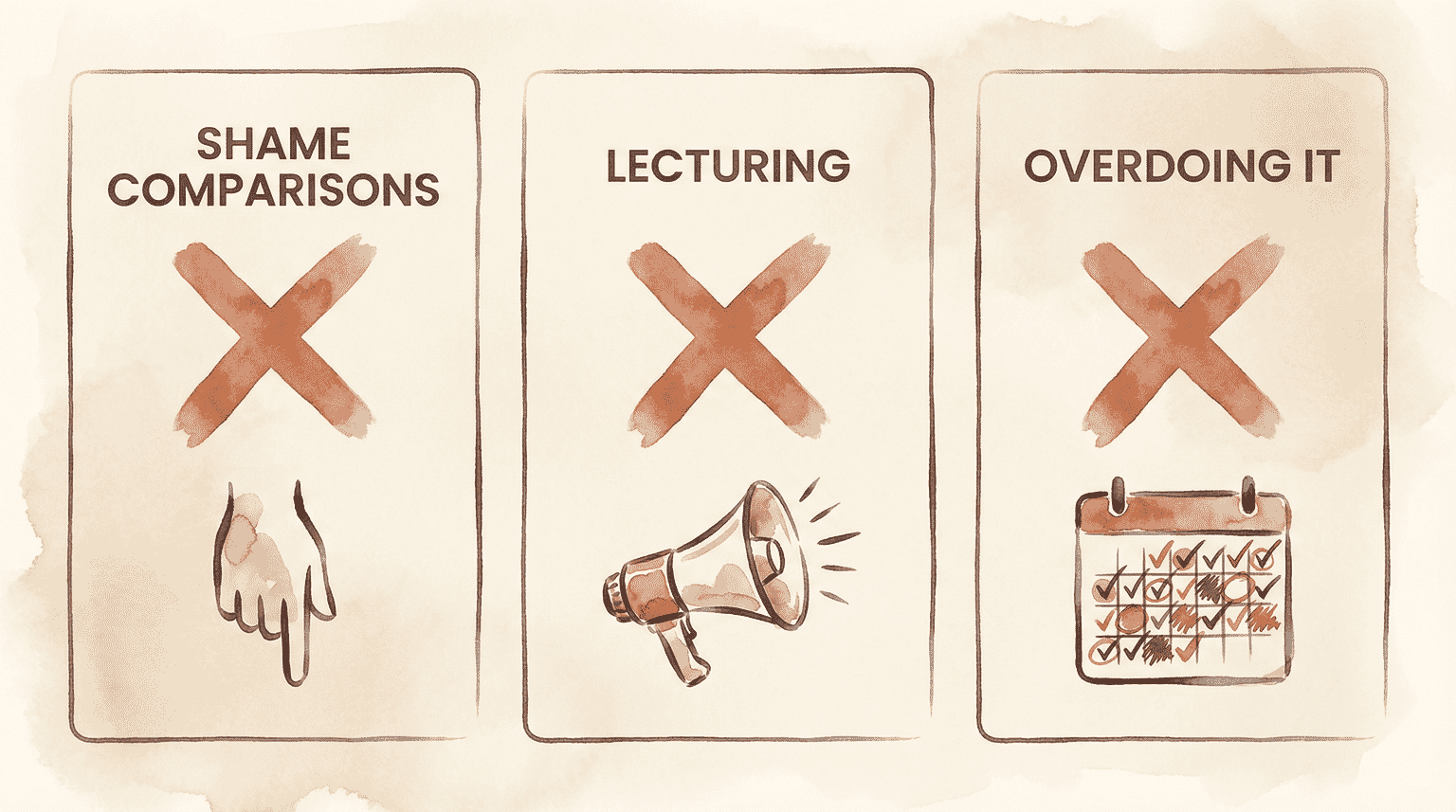

- Shame-based comparisons (“kids in other countries have nothing”) don’t build gratitude—they build guilt

- Your own gratitude practice matters more than instruction—grateful parents tend to raise grateful kids

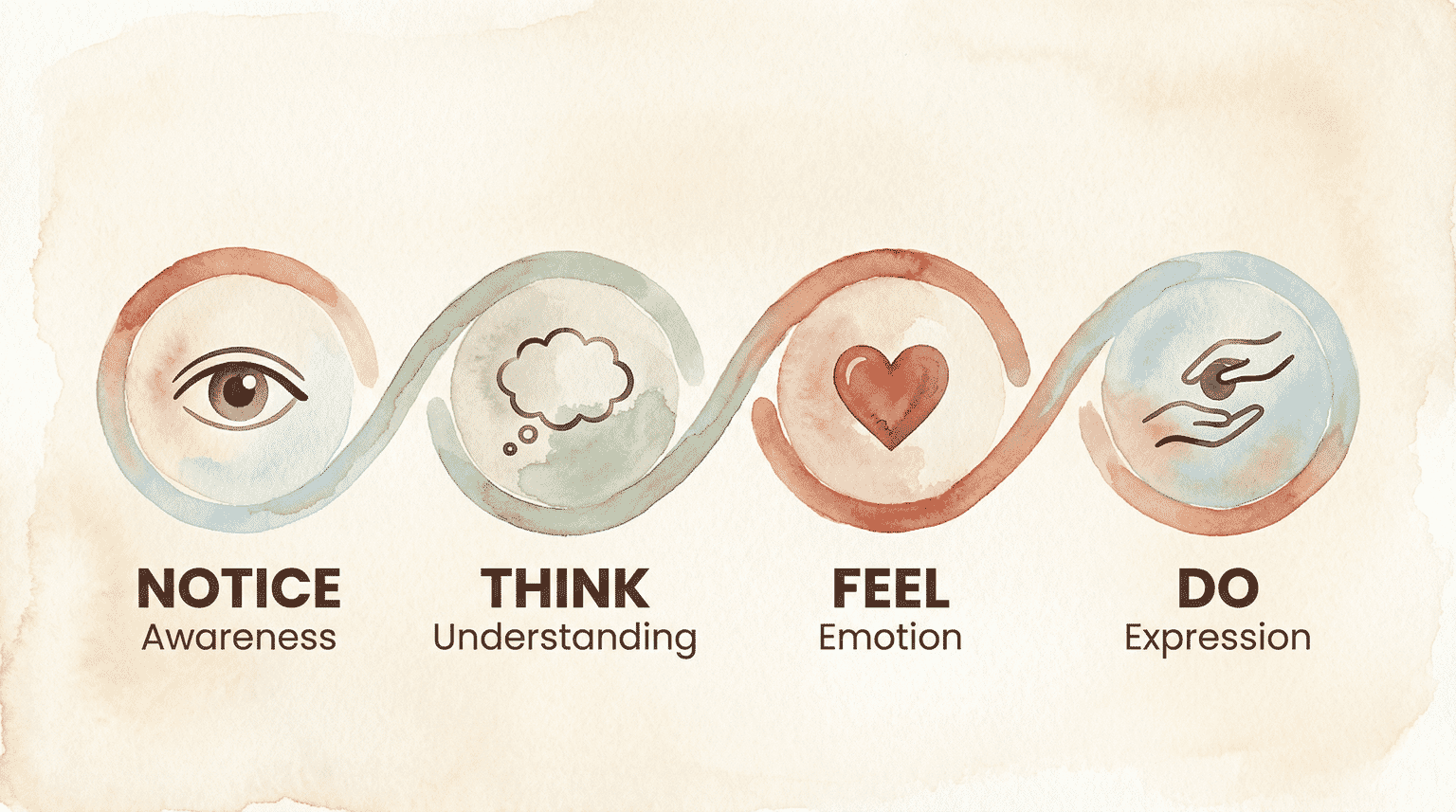

The Four Components Model: Notice, Think, Feel, Do

Andrea Hussong, PhD, who leads UNC Chapel Hill’s Raising Grateful Children project, has spent years studying how gratitude actually develops in children. In a Harvard EdCast interview (2023), she explained her research-based framework:

“We talk about gratitude as sort of having four beats. It’s what you notice, that you either have or have been given… And then it’s how do you make sense of that thing that you have? And it’s your thoughts and feelings about it that is going to lead you to feeling grateful or not.”

— Andrea Hussong, PhD, Director of UNC Chapel Hill’s Raising Grateful Children Project

Here’s the framework in action:

- Notice — Recognizing what you have or have been given

- Think — Understanding why someone gave or did something for you

- Feel — Experiencing positive emotions connected to receiving

- Do — Expressing appreciation through words or actions

When your child seems “ungrateful,” the breakdown is happening somewhere in these four beats. Maybe they didn’t notice what they received. Maybe they noticed but didn’t connect it to someone’s thoughtfulness. Maybe they understood intellectually but didn’t feel anything. Or maybe they felt grateful but didn’t know how to show it.

This is why generic prompts fail—they skip straight to “Do” without building the foundation. Understanding the four components gives you specific places to intervene.

Component #1: NOTICE (Awareness)

The first beat is simply becoming aware of what you have or what someone did for you. This sounds obvious, but children—especially young ones—often don’t register gifts or kindness as anything special. It’s just… there.

What noticing looks like

For my 4-year-old, noticing is very present-moment and concrete. Research from Community Early Learning Australia (2022) confirms this: preschoolers are most grateful for people, positive experiences, and food—not abstract concepts. My older kids can notice more subtle things: that their friend saved them a seat, or that I remembered their favorite snack.

Even young children can tell the difference between authentic appreciation and going through the motions. This is why forced “thank yous” often feel hollow to everyone involved.

By age six, kids have developed enough social awareness to recognize when gratitude is genuine versus performative—which means they know when they’re being performative too.

Parent scripts that build noticing

- “What was something good about today?”

- “Did you notice that Grandma packed your favorite cookies?”

- “What’s something you have that you really like?”

When kids say “nothing” or “I don’t know”

This happens constantly in my house. Don’t give up. Try getting more specific: “What was something you ate today that tasted good?” or “Was there a moment when you laughed?”

You’re training their attention toward positives—and that muscle takes practice. I’ve watched my 8-year-old go from “nothing happened” to genuinely identifying moments after a few weeks of consistent, low-pressure questions.

Component #2: THINK (Understanding)

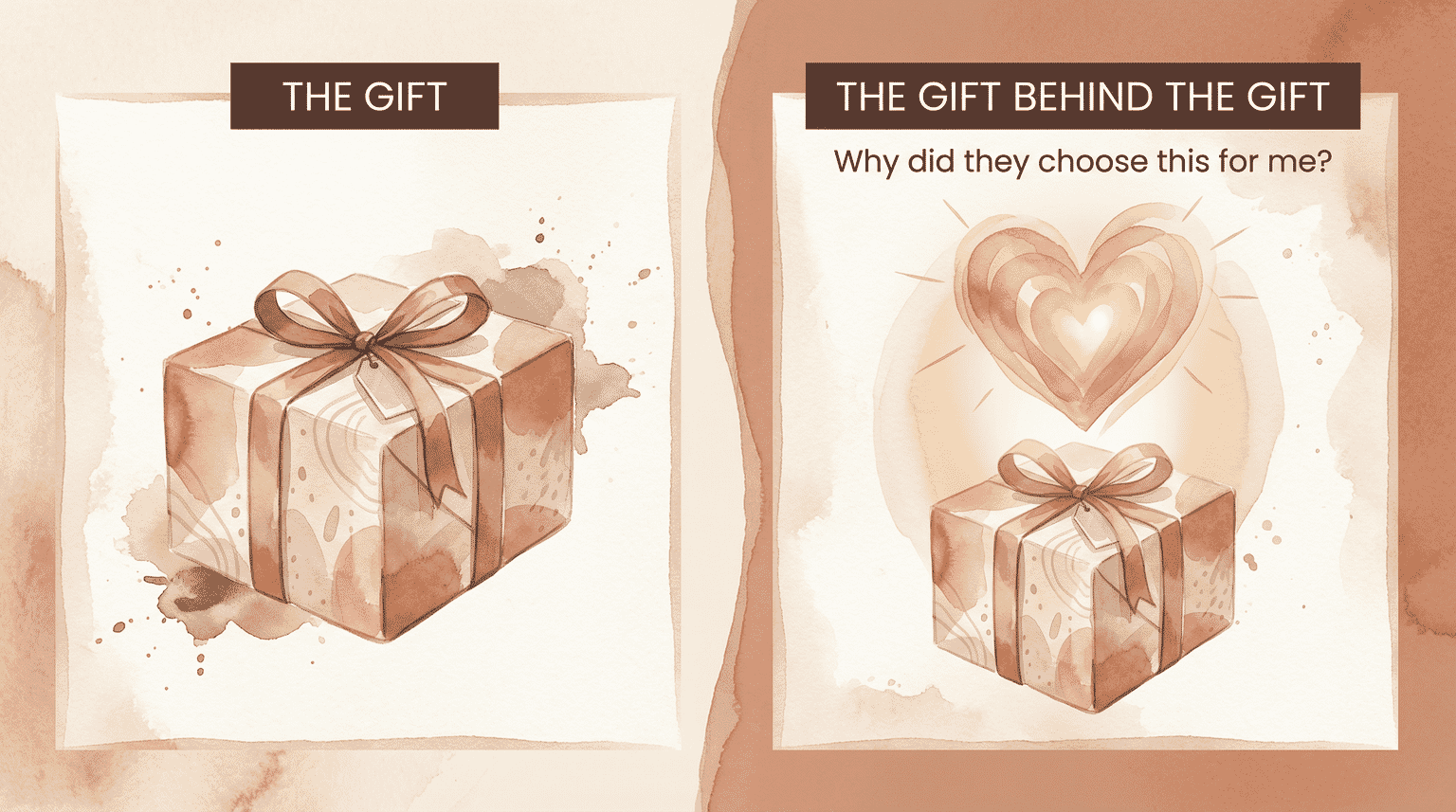

Once children notice what they received, they need to make sense of it. This is where perspective-taking comes in: Why did someone give this to me? What effort or thought went into it?

Hussong calls this finding “the gift behind the gift.” When a child understands that Aunt Sarah chose the butterfly sweater because she remembered a conversation from six months ago, gratitude becomes personal and relational—not just about the object.

What thinking looks like

The APA (2023) explains that the brain regions involved in social information processing—understanding others’ intentions—are still developing in young children. My 2-year-old cannot do this yet. My 6-year-old is just starting. By 10, my kids can genuinely reflect on why someone might have chosen something specific for them.

Parent scripts that develop thinking

- “Why do you think Grandpa picked that book for you?”

- “What do you think she was hoping you’d feel when she gave you this?”

- “How do you think he knew you’d like it?”

When kids focus only on the object

This is developmentally normal for younger children. Instead of correcting, gently redirect: “I noticed Grandma wrapped this so carefully. She must have been excited to give it to you.” You’re modeling the thinking process out loud—showing them what that second beat looks like.

Component #3: FEEL (Emotional Connection)

Here’s where many parents try to force it—and where forcing always backfires. The third component is actually experiencing positive emotions connected to receiving something.

You cannot lecture a child into feeling grateful. The feeling has to arise naturally from noticing and thinking.

What feeling looks like

Christina Karns, a neuroscientist at the University of Oregon, explains that for toddlers and preschoolers who don’t yet have complex perspective-taking abilities, “just sharing the sensory aspects of feeling good is appropriate.” My 4-year-old’s gratitude feeling is excitement. My 15-year-old’s might be a quiet warmth she doesn’t even verbalize.

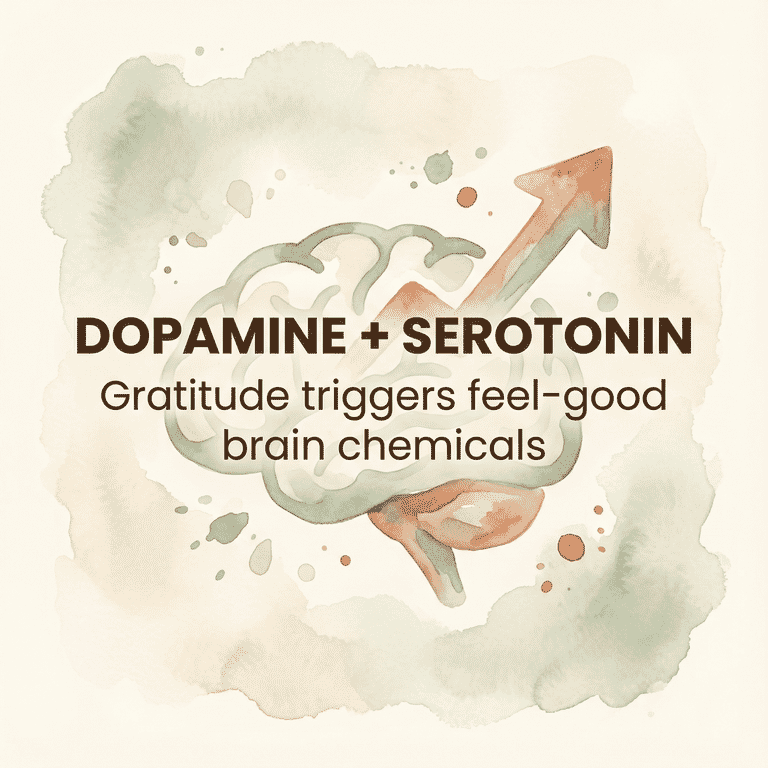

University of Rochester (2024) explains why these feelings matter neurologically: focusing on thankfulness triggers dopamine and serotonin release, reducing anxiety and depression over time.

This connects to the broader science of how gifts affect children’s brains. The emotional component isn’t just nice to have—it’s creating real changes in brain chemistry.

Parent scripts to support feeling

- “How did it make you feel when she remembered you like that?”

- “What’s it like knowing he thought about you?”

- “Does that give you a warm feeling inside?”

When kids seem emotionally flat

Don’t panic. Some children process internally and won’t show obvious emotion. Others are overwhelmed and need time. I’ve learned with my quieter kids to circle back later: “I noticed you got pretty quiet when you opened that. How are you feeling about it now?”

Component #4: DO (Expression)

Only after noticing, thinking, and feeling can expression become genuine. The “Do” component is what most parents fixate on—but it’s actually the final step, not the starting point.

Beyond “say thank you”

Expression can take many forms: verbal thanks, written notes, drawings, hugs, helping the person, or using the gift in front of the giver. If you’re looking for strategies on getting kids to write thank-you notes, that’s one important avenue—but it’s not the only way children show appreciation.

Parent scripts for expression variety

- “How could you show her you appreciated it?”

- “What’s a way to let Grandpa know this meant something to you?”

- “Would you like to draw a picture or tell her in person?”

When thank-yous feel forced

Psychology Today (2023) found that children displayed more gratitude on days when parents talked about gratitude more frequently—but through questions and conversation, not demands. If expression feels robotic, back up to the earlier components. Genuine expression follows genuine feeling.

Common Mistakes That Backfire

My librarian instincts kicked in here: I wanted to know what doesn’t work. Turns out research has clear answers.

Mistake #1: Shame-based social comparisons

The temptation to point out how good our kids have it compared to others is strong. But Hussong’s research shows this approach backfires.

“Particularly parents who have more privilege in their families, they use social comparison a lot to try to invoke gratitude… We can inadvertently give the message that having less stuff is somehow not as good.”

— Andrea Hussong, PhD, UNC Chapel Hill

I’ve caught myself doing this. It doesn’t build gratitude—it builds guilt. And guilt isn’t the same thing.

Mistake #2: Lecturing instead of asking

Hussong’s research emphasizes: “It’s really about just walking them through that reflection piece—not talking for them or lecturing them about how grateful they should be, but just asking some really open-ended questions.”

Mistake #3: Overdoing it

This surprised me. The APA reports that people who expressed gratitude once a week—but not three times a week—reported greater well-being. Harvard researcher Dr. Milena Batanova warns: “If you’re talking to your kids about what they’re grateful for too often, it can water down the effects, or bore them. Then it can have a counterproductive effect.”

Mistake #4: Forcing expression before feeling develops

When we demand “say thank you” before the emotional groundwork exists, we’re training performance, not gratitude.

Mistake #5: Reacting negatively when kids aren’t grateful

When your child blows it—and they will—Hussong recommends taking their perspective first before guiding them toward awareness. If you need specific strategies for handling those ungrateful moments, a measured response matters more than an immediate one.

The Parent Modeling Effect

Here’s research that gave me permission to focus on myself: a 2023 study from Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center found that on days parents felt more gratitude, they experienced greater well-being and felt closer to their children—regardless of how challenging caregiving was that day.

Earlier research from Applied Developmental Science established that grateful parents tend to raise grateful kids. Not through instruction, but through demonstration.

The researchers put it this way: “Parents can improve their well-being, relationships with their children, and family functioning, not necessarily by engaging in more intense parenting practices or increasing engagement with their children, but by practicing simple positive activities—namely, gratitude.”

When I verbalize my own gratitude—”I’m so glad we have this cozy house on such a cold night”—I’m showing my kids what the internal process looks like. My 8-year-old has started mimicking this. Not because I told him to. Because he heard me do it.

Building Gratitude Habits That Stick

The research on frequency is clear: once weekly is the sweet spot. Emmons and McCullough’s foundational research found that weekly gratitude journaling for ten weeks produced significant increases in well-being.

This finding freed me from the pressure of daily gratitude rituals. Once a week is not only enough—it’s actually better than more frequent practice.

The key is consistency over intensity. A weekly habit maintained for months beats a daily practice that fizzles after two weeks.

Ritual suggestions that actually work

- Dinnertime rounds: Each person shares one thing they’re grateful for (we do this maybe twice a week, not daily)

- Bedtime reflection: “What was something good about today?” as part of the tucking-in routine

- Car rides: The captive-audience commute is perfect for casual gratitude conversations

The key: integrate into existing routines rather than adding new tasks. With eight kids, I don’t have bandwidth for elaborate gratitude journals. But I can ask one question at dinner.

If you want to explore why gratitude rituals work on a deeper level—and why consistency matters more than intensity—the psychology is fascinating.

What Developing Gratitude Actually Looks Like

Here’s a quick reference for calibrating expectations:

| Age | What Each Component Looks Like |

|---|---|

| 2-5 | Concrete, present-moment focus. Grateful for pudding at lunch, not abstract kindness. Sensory experience of feeling good is appropriate. |

| 6-8 | Emerging understanding of others’ intentions. Needs scaffolding through questions. Can recognize genuine vs. performative gratitude. |

| 9-11 | Abstract reasoning developing. Can identify the “gift behind the gift.” Less parental structuring needed. |

| 12+ | Can generate own gratitude perspectives. May resist family rituals—needs autonomy respected. Gratitude often expressed privately. |

Research suggests gratitude commonly emerges fully between ages 7 and 10. A 2024 study links gratitude to happiness in children by age five—but expecting a 5-year-old to independently demonstrate all four components isn’t realistic.

Understanding these stages is part of teaching values through gifts—meeting children where they developmentally are, not where we wish they were.

Frequently Asked Questions

At what age can children understand gratitude?

Children have capacity for gratitude from early development, though it commonly emerges fully between ages 7 and 10. Research links gratitude to happiness by age five. Young children (2-5) understand gratitude concretely—they’re grateful for pudding at lunch, not abstract kindness. Complex perspective-taking develops as brain regions for social processing mature.

What are the four components of gratitude?

The Four Components Model identifies gratitude as having four “beats”: Notice (awareness of what you have or received), Think (understanding why someone gave it), Feel (emotional response to receiving), and Do (actions expressing appreciation). Developed by UNC Chapel Hill’s Raising Grateful Children project, this framework shows parents where to intervene when gratitude isn’t developing naturally.

How often should kids practice gratitude?

Research suggests once weekly is more effective than daily practice. A study found that people expressing gratitude once weekly reported greater well-being than those practicing three times weekly. Harvard’s Dr. Milena Batanova warns that talking about gratitude too often “can water down the effects, or bore them.”

Why does my child seem ungrateful?

Children’s brains are still developing the regions responsible for social processing and perspective-taking—skills essential for gratitude. Rather than labeling a child as ungrateful, identify which component they might be missing: noticing, thinking about the giver’s intention, connecting emotionally, or knowing how to express appreciation.

I’m Curious

Which component of gratitude does your child struggle with most—noticing, thinking, feeling, or expressing? I’d love to hear what’s worked for building each piece. These specific strategies help other parents know where to focus.

I read every response—your experiences help me refine these strategies.

References

- Harvard EdCast: How to Raise Grateful Children – Four Components Model framework and research-based strategies from UNC Chapel Hill

- American Psychological Association – Frequency guidance and developmental brain research

- Greater Good Science Center, UC Berkeley – Research on parental gratitude benefiting children

- St. Louis Children’s Hospital – Gratitude’s role in emotional development

- Parent Magazine Florida – Age-specific gratitude research findings

- Community Early Learning Australia – Gratitude in young children

- University of Rochester Medical Center – Neurological benefits of gratitude

- Psychology Today – Evidence-based gratitude conversation strategies

Share Your Thoughts