Your sister-in-law hands your 5-year-old a beautifully wrapped present. He tears it open, glances at the book inside, and announces to the room: “I already have books. I wanted a dinosaur.”

Your face goes hot. Your sister-in-law’s smile freezes. And somewhere in your brain, you’re simultaneously planning an apology, a punishment, and wondering what you did wrong as a parent.

I’ve lived this moment eight times over. With eight kids ages 2 to 17, I’ve watched disappointed gift reactions play out at birthday parties, Christmas mornings, and random Tuesday afternoons when Grandma drops by with surprises. Here’s what I finally learned after years of cringing and course-correcting: this isn’t a character flaw—it’s a skill deficit with a developmental timeline.

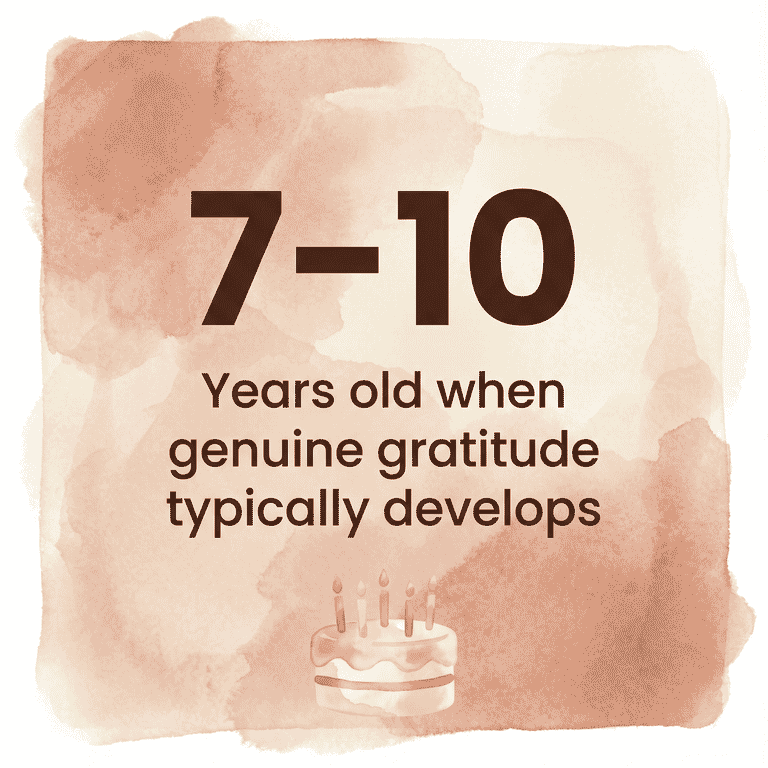

Research from UNC Chapel Hill confirms that genuine gratitude commonly emerges between ages 7 and 10. Before that, children are still developing the cognitive ability to notice kindness, attribute their feelings to someone else’s effort, and then express appropriate thanks. That’s three separate mental steps that adults do automatically—but kids have to learn them one at a time.

“Research consistently shows that children, regardless of age, who are more naturally prone to feeling grateful for things—those kids tend to have better outcomes.”

— Dr. Hasti Raveau, Licensed Clinical Psychologist

So yes, this matters. But the path to raising grateful kids isn’t through shame—it’s through understanding and practice.

Key Takeaways

- Genuine gratitude typically develops between ages 7-10—before that, ungrateful reactions reflect brain development, not character flaws

- Research shows punishing ingratitude increases compliance but doesn’t build real gratitude—and may cause anxiety years later

- The Notice, Think, Feel, Do framework walks children through the three cognitive steps required for genuine thankfulness

- Prevention works better than correction—preview gift situations and practice responses before they happen

- Brief acknowledgment in the moment, teaching conversation later is more effective than public correction

What’s Actually Happening When Your Child Rejects a Gift?

Before diving into specific scenarios, you need to understand what’s happening developmentally. This isn’t about excusing the behavior—it’s about responding effectively.

Research published in Cognitive Development found something surprising: before age 7, children believe saying “thank you” means they have to give a present back. They interpret gratitude as a promise to reciprocate—an obligation they feel unable to fulfill. So they avoid it altogether.

Here’s the other piece: the prefrontal cortex, which handles emotional regulation and gratitude expression, is the least-developed brain region in young people. Your child isn’t choosing to be rude. Their brain literally hasn’t finished building the hardware required for graceful responses.

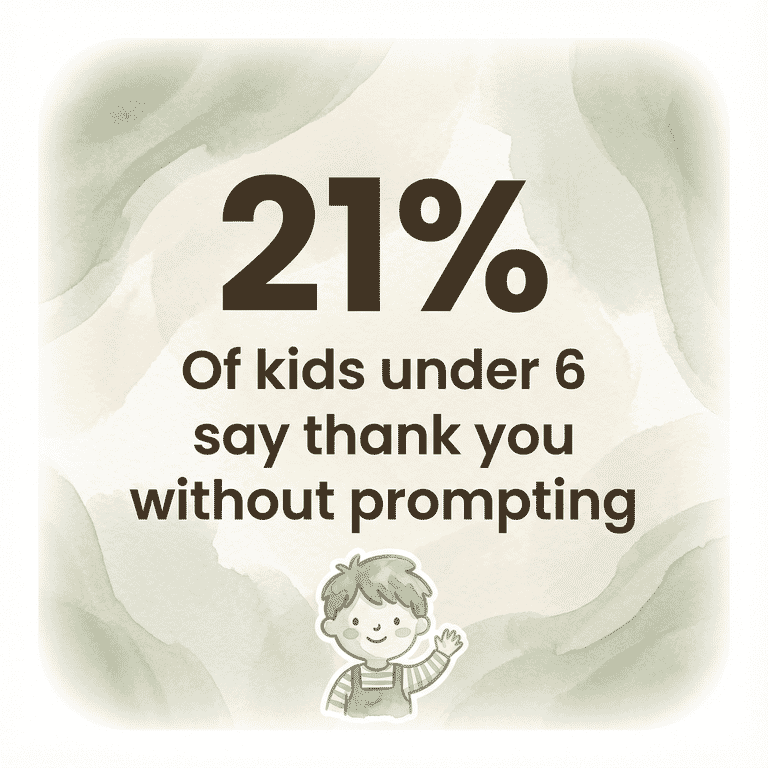

In one Halloween study of children saying thank you, researchers found only 21% of children under six said thank you without prompting, compared to 88% of children over eleven.

That’s not a parenting failure—that’s brain development doing exactly what it does. The gap closes naturally as children mature, but it takes years, not weeks.

Scenario One: Christmas Morning Overwhelm

The setup: Multiple gifts, high excitement, extended family watching, phone cameras recording everything.

What’s happening: Sensory overload plus expectation mismatch. Your child imagined opening one specific thing. Instead, they’re rapidly cycling through presents while everyone watches. Their disappointment—when it comes—gets amplified by the audience.

What to do:

- Slow the pace. One gift at a time, with pauses between.

- Position yourself near your child for quiet support.

- Prepare gift-givers in advance: “Kids this age often have big reactions. We’re working on it.”

What to say:

In the moment: “I can see you were hoping for something different. Let’s set this one aside and come back to it.”

To the gift-giver: “Thank you so much for thinking of her. She’s a bit overwhelmed right now—we’ll make sure she really looks at this later.”

Follow-up with your child (later): “That felt disappointing. What were you hoping for? [Listen.] It’s okay to feel that way. Grandma put a lot of thought into choosing something for you.”

What NOT to do: Don’t force immediate “say thank you” in front of everyone. Don’t lecture in the moment.

A UC Berkeley longitudinal study following 100+ families found that punishment increased outward compliance but did NOT build genuine gratitude—and was associated with more depression and anxiety symptoms three years later. Brief acknowledgment now, teaching conversation later. This is one of the most common gift-giving challenges families face.

Scenario Two: The Birthday Party Meltdown

The setup: Peers present, social stakes high, your child opens a gift and visibly rejects it—or worse, announces they didn’t want it.

What’s happening: Social comparison intensifies disappointment. Your child sees what friends brought and makes instant judgments. The public setting amplifies everyone’s shame response, including yours.

What to do:

- Keep your face neutral and calm. Your regulation models theirs.

- Brief, quiet intervention—not a public correction.

- Move the moment along rather than dwelling.

What to say:

In the moment (quietly): “I know. We’ll talk about it later. Right now, let’s say thank you and keep going.”

To the gift-giver: “Thank you so much for coming!” [Brief, no over-apologizing—that magnifies the moment.]

To other parents (if they notice): “Oh, you know how it is at this age—so much excitement!”

Follow-up: “At your party, when you opened [friend’s] gift, your face showed you were disappointed. How do you think [friend] felt when they saw that?”

What NOT to do: Don’t publicly shame or lecture. Don’t apologize excessively to the gift-giver. Research from Stony Brook University found that children consistently underestimate how happy recipients are when receiving gifts—they don’t realize what giving meant to the other child. That’s a teaching opportunity for later, not a lecture in the moment.

Scenario Three: The Grandparent Visit

The setup: Grandparent arrives with a carefully chosen gift. Your child responds with indifference or outright rejection. Grandparent’s face falls visibly.

What’s happening: Generational expectations differ significantly. Grandparents often remember thank-you notes and formal gratitude expressions as immediate requirements. They may interpret your child’s response as rudeness when it’s developmental limitation.

What to do:

- Acknowledge the grandparent’s feelings—research shows authentic emotional expression helps children learn.

- Don’t force performative gratitude.

- Have a brief private word with the grandparent if needed.

What to say:

In the moment: “Mom, thank you so much for this. [To child] Grandma picked this out especially for you.”

To grandparent (privately): “I know that felt disappointing. Kids this age are still learning how to show gratitude—the research says it doesn’t really click until 7 to 10. She does appreciate it; she just can’t show it the way we’d expect yet.”

Follow-up with your child: “Grandma drove all the way here to bring you something special. What do you think she was feeling when you said you didn’t want it?”

What NOT to do: Don’t force an immediate thank-you note. Don’t pretend the reaction didn’t happen—this dismisses the grandparent’s valid feelings. If you’re working on teaching children about the meaning behind gifts, these moments become learning opportunities rather than disasters.

Scenario Four: The Surprise Gift

The setup: Unexpected gift with no preparation time—neighbor drops by, relative sends a package, you bring home a “just because” present.

What’s happening: No preview means no expectation management. Your child’s unfiltered reaction emerges because they had no time to prepare a gracious response (a skill that takes years to develop).

What to do: Accept that surprise gifts carry higher disappointment risk. Keep your own expectations in check. Use the moment for observation, not correction.

Think of surprise gifts as data collection opportunities. How does your child respond without preparation? This tells you what skills they still need to develop.

What to say:

In the moment: “Oh, look what [person] sent! That was kind of them to think of you.”

If the reaction is negative: “I can see that wasn’t what you were expecting. Let’s put it here and you can look at it more later.”

Follow-up: “When someone surprises you with a gift, they don’t know exactly what you’d pick. They just wanted to make you happy. Does that change how you feel about it?”

What NOT to do: Don’t use surprise gifts as “tests” of gratitude. Don’t withhold the gift as punishment for a poor reaction. Use this as data for what to preview before major gift occasions.

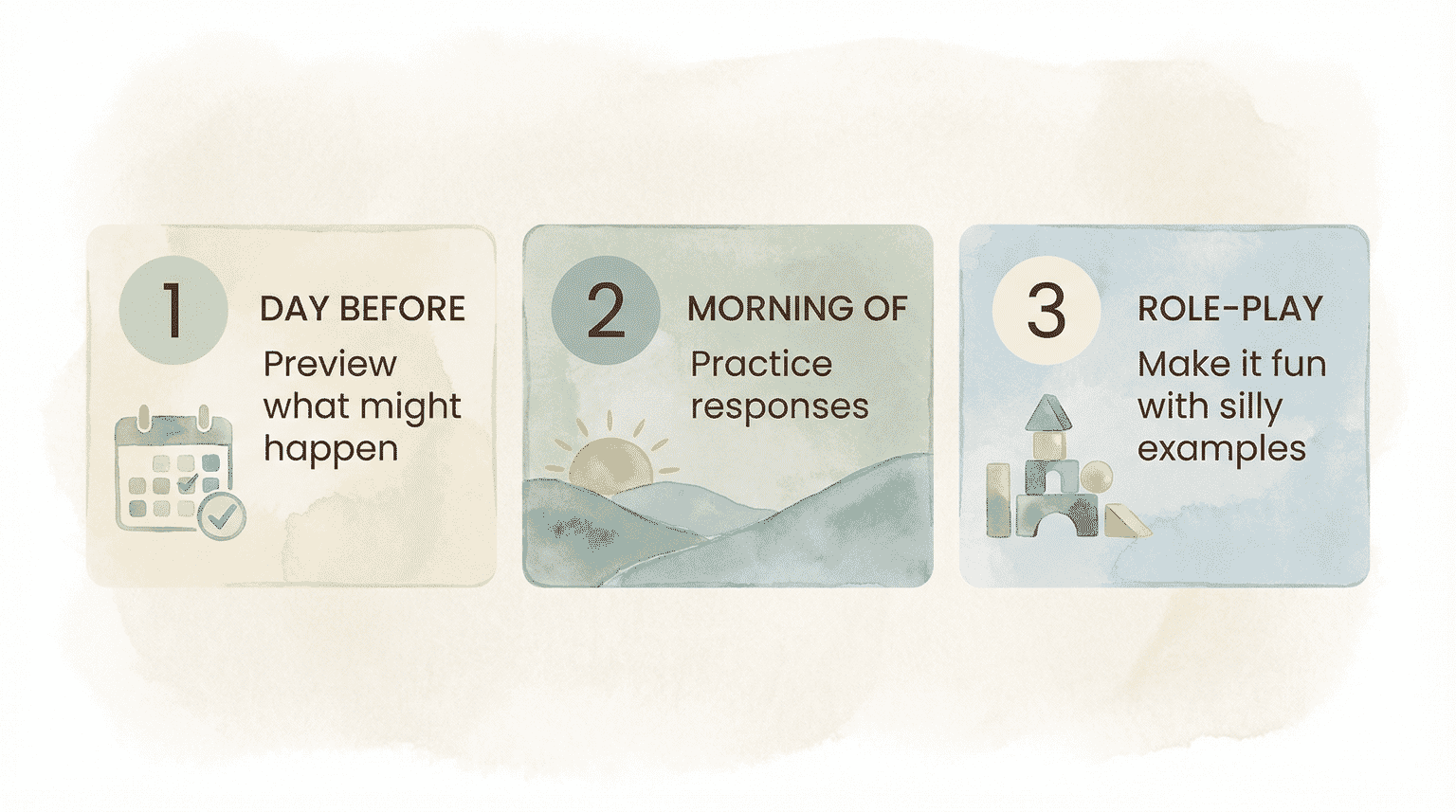

The Prevention Playbook: Before Gifts Happen

The best time to handle ungrateful reactions is before they occur. Here’s my preparation protocol after managing countless gift situations:

1-2 days before the event: “Tomorrow at Grandma’s, you might get a present. Sometimes gifts are exactly what we hope for, and sometimes they’re different. Either way, the person giving it wanted to make you happy.”

Morning of: “Remember what we talked about? What’s something you can say if you open a gift and it’s not what you expected?”

Role-play option: Practice receiving a “pretend” disappointing gift with silly alternatives. (“What if Grandma got you a potato?”) This makes it playful while building the skill.

Year-round practices:

- Model your own gratitude aloud: “I’m so glad my friend thought of me.” Research shows that on days when parents model gratitude, children show more gratitude that same day.

- Involve children in selecting and giving gifts to others.

- Narrate gift-giver’s perspective: “Uncle Mike spent time picking this—he thought you’d love the colors.”

What NOT to Do: The Evidence Against Punishment

I want to be direct about this because it contradicts most parents’ instincts.

Andrea Hussong’s research at UC Berkeley found that punishing ingratitude increased outward compliance but was associated with more depression and anxiety symptoms three years later—without building genuine gratitude.

As Hussong puts it: “It may well be that parents’ punishing behaviors accomplish greater compliance in the behavior of gratitude… but have little impact on the actual experience of gratitude.”

In other words, you can force a “thank you” but you can’t force the feeling behind it. And the forcing might cause harm.

Common mistakes:

- Forcing immediate public apology

- Taking the gift away as punishment

- Lecturing in front of others

- Threatening future gift loss (“If you can’t be grateful, you won’t get anything next time”)

What works instead:

- Brief acknowledgment, teaching conversation later

- Authentic (mild) emotional expression: “I felt sad when you said that, because Grandpa worked hard to find it”

- Practice, not punishment

Teaching Real Gratitude: The Notice, Think, Feel, Do Framework

Cognitive neuroscientist Anne-Kathrin Eiselt recommends a four-step process for building genuine gratitude:

- Notice: “What do you see about this gift? What color is it? What can it do?”

- Think: “Why do you think [person] chose this for you?”

- Feel: “How does it feel to know someone was thinking about you?”

- Do: “What’s one way you could show [person] you appreciate them thinking of you?”

Use this during follow-up conversations, not in the moment. It works because gratitude requires three developmental stages—awareness, meaning-making, and expression—and this framework walks children through all three rather than jumping straight to forced “thank you.”

The key is patience. You might have this conversation dozens of times before it clicks. That’s normal. That’s brain development.

When to Be Concerned

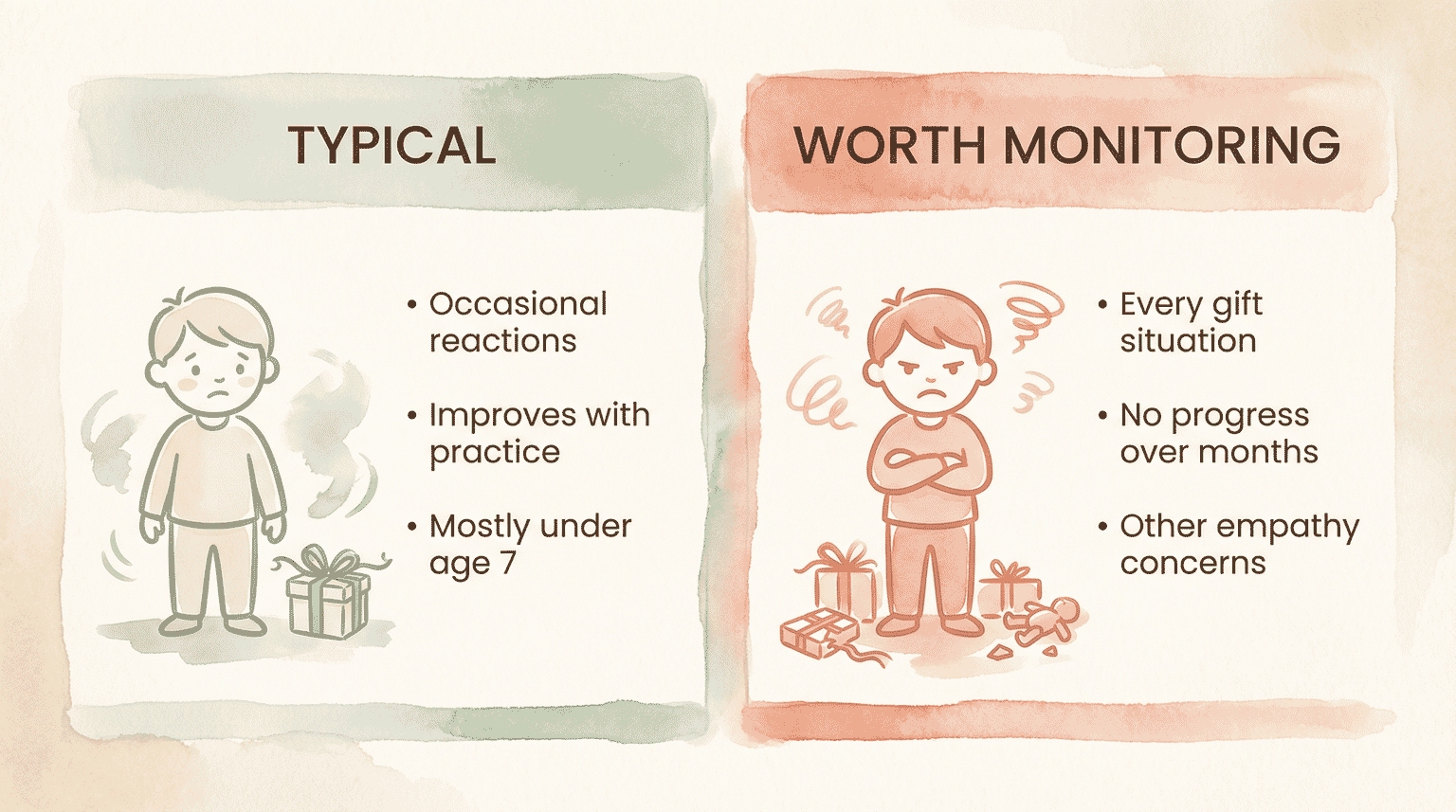

Normal: Occasional ungrateful reactions, especially under age 7. Improvement with preparation and practice over time.

Worth monitoring: Consistent reactions across ALL gift situations regardless of preparation. No progress after months of consistent coaching. Accompanied by other empathy deficits.

For detailed age-by-age gratitude development, see How to Teach Kids Gratitude.

Recovery Scripts: What to Say After

To the gift-giver (later): “I wanted to thank you again for [gift]. I know [child’s] reaction wasn’t what any of us hoped for. Kids this age are still developing the ability to manage disappointment and show gratitude—it usually clicks between 7 and 10. We’re working on it, and your gift means a lot to our family.”

To your child (same day or next day): “I want to talk about what happened when you opened [gift]. I’m not mad. I just want to understand. What were you feeling right then?” [After listening] “Those feelings are okay to have. But [gift-giver] didn’t know you felt that way—they just saw your face and felt hurt. What could you do next time that lets you feel disappointed AND helps them feel appreciated?”

To yourself: One disappointing moment doesn’t define your child’s character. This is a skill deficit, not a moral failure. Progress happens over years, not incidents.

University of Louisville psychologist Dr. Nicholaus Noles offers reassurance that should comfort every parent who’s lived through these moments.

“Don’t sweat it, they will get it eventually. Be gracious and show gratitude, and your kids will pick it up.”

— Dr. Nicholaus Noles, University of Louisville

I’ve watched this happen eight times now. The 17-year-old who once announced she hated her birthday present in front of everyone? She now writes thoughtful thank-you texts unprompted. The brain catches up. The skills develop. Your job is to guide the process without derailing it through shame.

Over to You

What’s your worst ungrateful gift moment—and what did you do in the moment? I’m collecting real stories because they help other parents feel less alone (and less mortified) when it happens to them.

I read every mortifying story—they’re proof we’re all figuring this out together.

References

- Techno Sapiens/Dr. Jacqueline Nesi – UNC Chapel Hill research on gratitude development stages

- Greater Good Science Center, UC Berkeley – Longitudinal study on parental response effectiveness

- Yahoo News/Cognitive Development journal – Dr. Nicholaus Noles research on children’s understanding of thank-you

- Parenting Translator – Research synthesis on ungrateful behavior statistics

- Detroit Free Press – Expert perspectives on gratitude and brain development

- Stony Brook University – Research on children’s understanding of giving impact

Share Your Thoughts