Your daughter unwraps the beautifully wrapped box from Grandma, and her face falls. “Oh,” she says flatly. “Another sweater.” You watch your mother’s expression shift from anticipation to hurt, and suddenly you’re managing two disappointed people while your own stomach drops.

Here’s what’s actually happening in your child’s brain—and it’s not ingratitude. Psychologists call it the “backfire condition,” where gratitude and disappointment exist simultaneously. A 2023 study published in Cognition and Emotion confirmed that receiving a disliked gift creates this specific emotional blend.

Your child can genuinely appreciate that Grandma thought of them and feel let down by what’s inside the box. These aren’t contradictory feelings—they’re coexisting ones.

And your child isn’t alone. Research published in Nature found that over 75% of gift recipients have received something they didn’t want. Gift disappointment isn’t a character flaw—it’s a near-universal human experience that children need to learn to navigate.

Key Takeaways

- Disappointment and gratitude naturally coexist—your child isn’t being ungrateful, they’re experiencing what researchers call the “backfire condition”

- Preview conversations before gift-giving events help children prepare for mixed feelings

- Gift rejection activates pain responses in givers’ brains—protecting relationships matters more than the gift itself

- Simple scripts like “Thank you for thinking of me!” express genuine appreciation without faking enthusiasm

- Gratitude is a trainable skill—practice with silly role-play before real gift-giving events

Why Gift Disappointment Hurts Everyone

Here’s something that shifted my perspective entirely: when a gift-giver sees disappointment on a recipient’s face, their brain processes it similarly to physical pain. The same Nature study found that gift rejection activates neural pathways associated with social exclusion—and this effect is stronger with close relationships like grandparents and family members.

Gift disappointment is nearly universal. Three out of four people have been on the receiving end of something they didn’t want—which means your child is learning to navigate an experience they’ll face throughout their entire life.

The difference is that adults have had decades to practice their poker faces. Your six-year-old hasn’t.

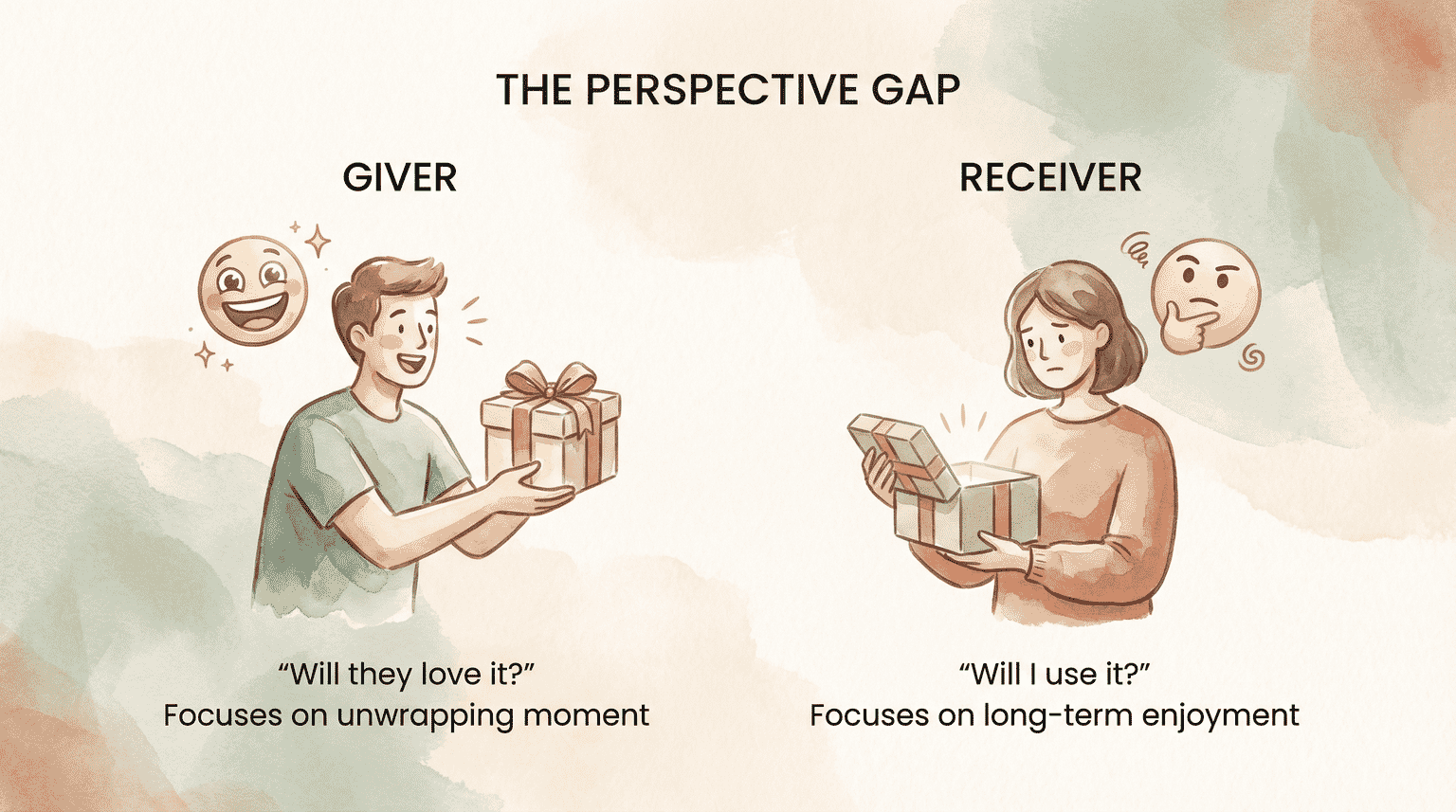

The neuroscience of gift-giving reveals an important tension between givers and receivers.

“There is a natural perspective gap… Givers focus on eliciting the biggest immediate reaction at the moment of exchange, even if the pleasure is short-lived.”

— Professor Adelle Yang, National University of Singapore

This means Grandma wasn’t being clueless about the sweater. She was imagining your daughter’s face lighting up. When that didn’t happen, she didn’t just feel mildly disappointed—she felt genuinely hurt.

Understanding this reframes why we teach gracious responses. It’s not about performing fake emotions or suppressing authentic ones. It’s about protecting relationships from real damage.

When we help children handle moments when they react ungratefully, we’re teaching them to care for the people who care about them.

Before the Gift: Prevention Scenarios

Before Christmas and Birthdays

What’s happening: Children build mental images of exactly what they’ll receive. The gap between expectation and reality creates disappointment before the gift is even unwrapped.

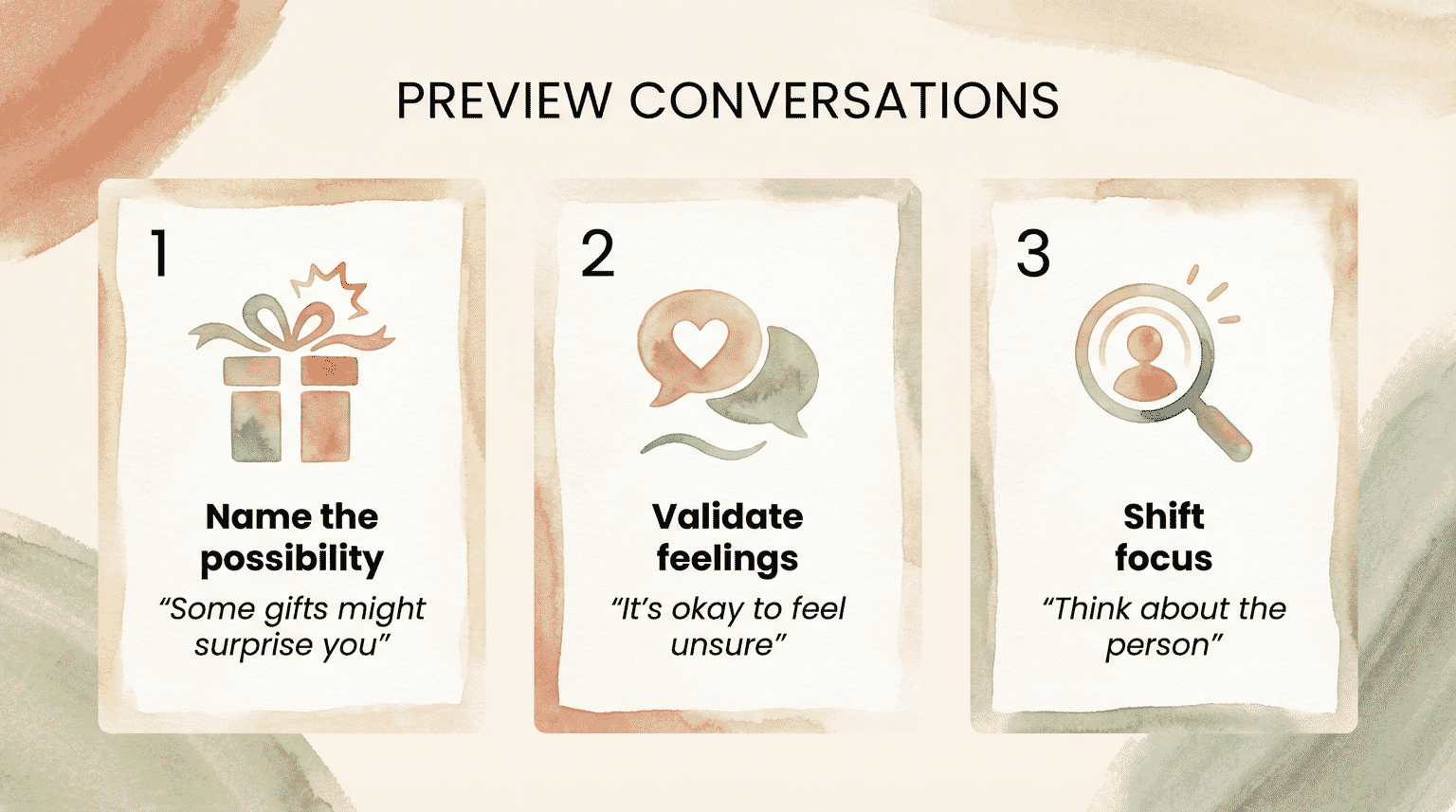

What to do: Have a preview conversation a few days before the event—not as a lecture, but as practical preparation.

What to say:

“Some gifts will be exciting, and some might surprise you in ways you didn’t expect. We can feel thankful for the person even if we’re not sure about the gift.”

I’ve found that naming this possibility in advance gives kids permission to have complex feelings without being blindsided by them.

Before Family Gatherings

What’s happening: Extended family chooses gifts based on their own memories, budgets, and ideas about what children like—which often differ dramatically from what your child actually wants. For guidance on handling truly inappropriate gifts, we have a separate guide.

What to do: Shift focus from the stuff to the relationship. This connects to your broader family gift-giving expectations and helps children understand that different families do things differently.

What to say:

“Grandma picked this because she was thinking about you. That’s the real gift—someone who loves you spent time imagining what would make you happy.”

Research supports this reframe. The “smile-seeking hypothesis” shows that givers focus on the unwrapping moment while receivers care more about long-term enjoyment. Neither perspective is wrong—they’re just different.

In the Moment: Response Scenarios

Scenario A: Christmas Morning Chaos

What’s happening: Multiple gifts, high excitement, exhausted children, watchful relatives, possibly sugar from breakfast treats. This is the hardest possible environment for emotional regulation.

What to do: Stay calm yourself. Your reaction sets the tone. This is about energy management, not moral failure.

Scripts for your child:

“Thank you! This is from you?”

“Wow, thank you for thinking of me!”

Scripts for you (whispered, if needed):

“Big smile, say thank you. We’ll talk about it later.”

What to avoid: Don’t demand “SAY THANK YOU” loudly in front of the giver. It embarrasses your child and highlights the awkward moment for everyone.

Scenario B: Birthday Party with Peers

What’s happening: Performance pressure is high. Your child is comparing gifts, managing social dynamics, and probably running on cake and adrenaline. Emotional regulation capacity is at its lowest.

What to do: Consider opening gifts after guests leave, or create a brief private opening time. If opening happens during the party, keep expectations realistic.

Scripts for your child:

“Thank you for coming to my party and bringing this!”

Scripts for you:

(Whispered) “Big smile, say thank you, we’ll talk later.”

Research on children’s emotional displays shows that even kids who can mask disappointment struggle to do so consistently—especially in high-stimulation environments.

First-graders are significantly less successful than older children at hiding reactions. This isn’t rudeness; it’s developmental reality.

Scenario C: One-on-One with Grandparents

What’s happening: An elderly relative may have spent significant money and emotional energy choosing this gift. They can’t easily return it. Their investment is high, and so is the potential for hurt.

What to do: Protect the relationship above all else. The gift can be addressed later; the relationship damage cannot be easily undone.

Scripts for your child:

“Thank you, Grandma. Can you tell me why you picked this?”

This question does something powerful—it shifts attention to the giver’s intention and often reveals a sweet story your child didn’t know.

Scripts for you (to the gift-giver):

“Mom, they loved that you thought of them.”

(Later, privately to your child):

“Grandma felt so happy giving that to you. Did you see her face when you asked about why she chose it?”

Scenario D: The Duplicate or Obvious Regift

What’s happening: Your child recognizes they already own this toy, or that the gift is clearly secondhand. They may feel confused or even insulted.

What to do: Redirect immediately to intention. The giver’s circumstances (limited budget, different awareness of your child’s collection) aren’t your child’s business to judge.

Scripts for your child:

“Thank you! Now I have two!”

Or simply:

“Thank you for this!”

Scripts for you:

“They wanted you to have something you’d enjoy. That’s what matters.”

After the Moment: Follow-Up Conversations

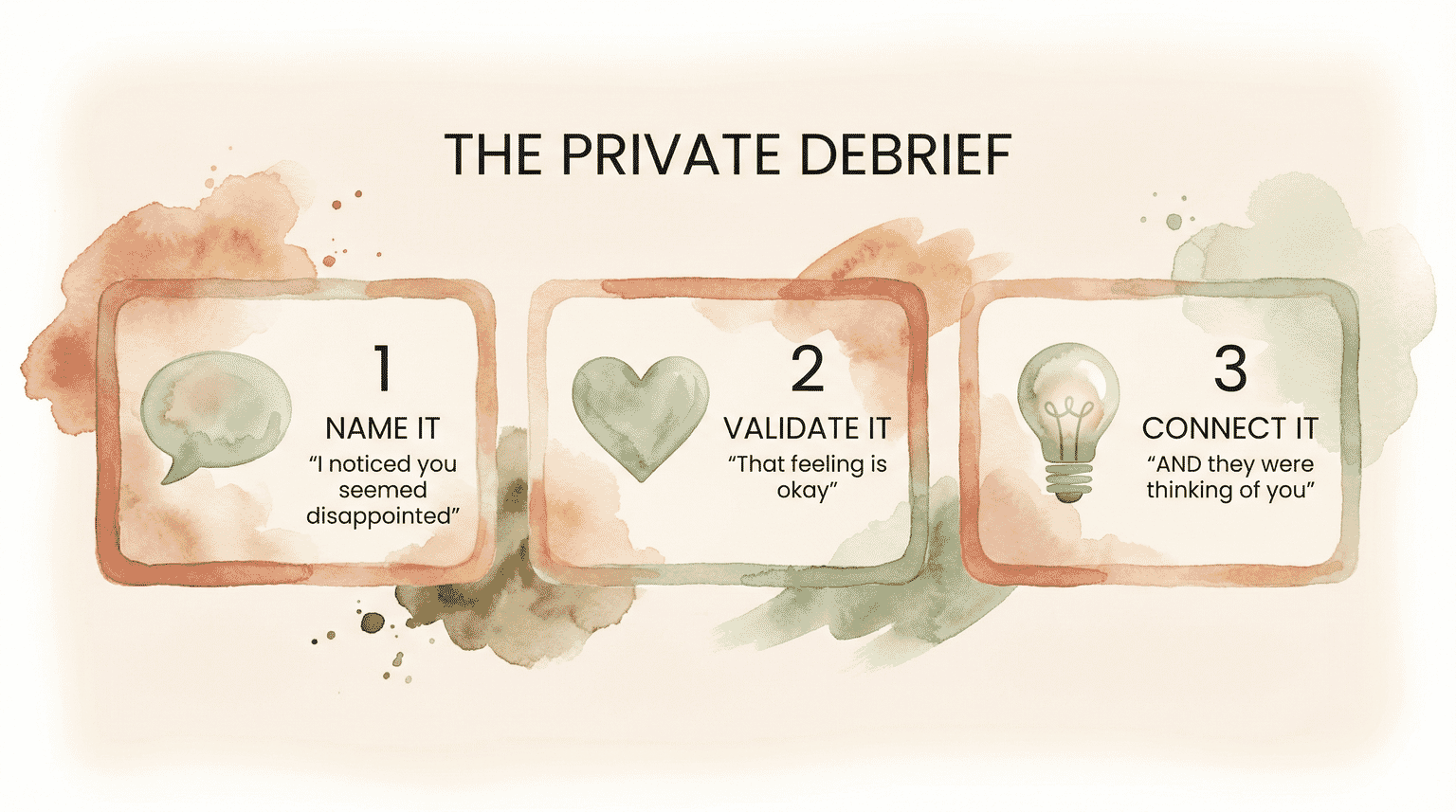

The Private Debrief

When: At least 30 minutes after the gift-opening moment, when emotions have settled.

What to say:

“I noticed you seemed disappointed about the building set from Uncle Mike. Want to talk about it?”

The goal: Validate the feeling while connecting it to the giver’s effort. Both things are true: the gift wasn’t what they wanted, AND Uncle Mike was thinking about them.

Developmental psychologists note that meaningful gratitude—actually understanding the giver’s intention—emerges gradually through early adolescence. Younger children won’t fully grasp this yet, but these conversations plant seeds.

The Thank-You Practice

When: Within 48 hours of receiving the gift.

What to do: Help your child write or draw a thank-you that focuses on the giver, not the gift. If you need detailed guidance, I’ve written about how to write meaningful thank-you notes without the usual battles.

What to say:

“What do you want Aunt Sarah to know about how you felt when she gave you that?”

This question bypasses the “but I didn’t like it” objection by focusing on the relational moment rather than the object.

The Exchange or Donate Discussion

When: Several days after the event, when emotions have fully settled.

What to say:

“Sometimes we receive things that aren’t quite right for us. We can talk about what to do with them—but the thank you always stays the same.”

This teaches an important lesson: gratitude for the giver’s intention is separate from keeping every gift forever.

Building the Gratitude Skill Through Practice

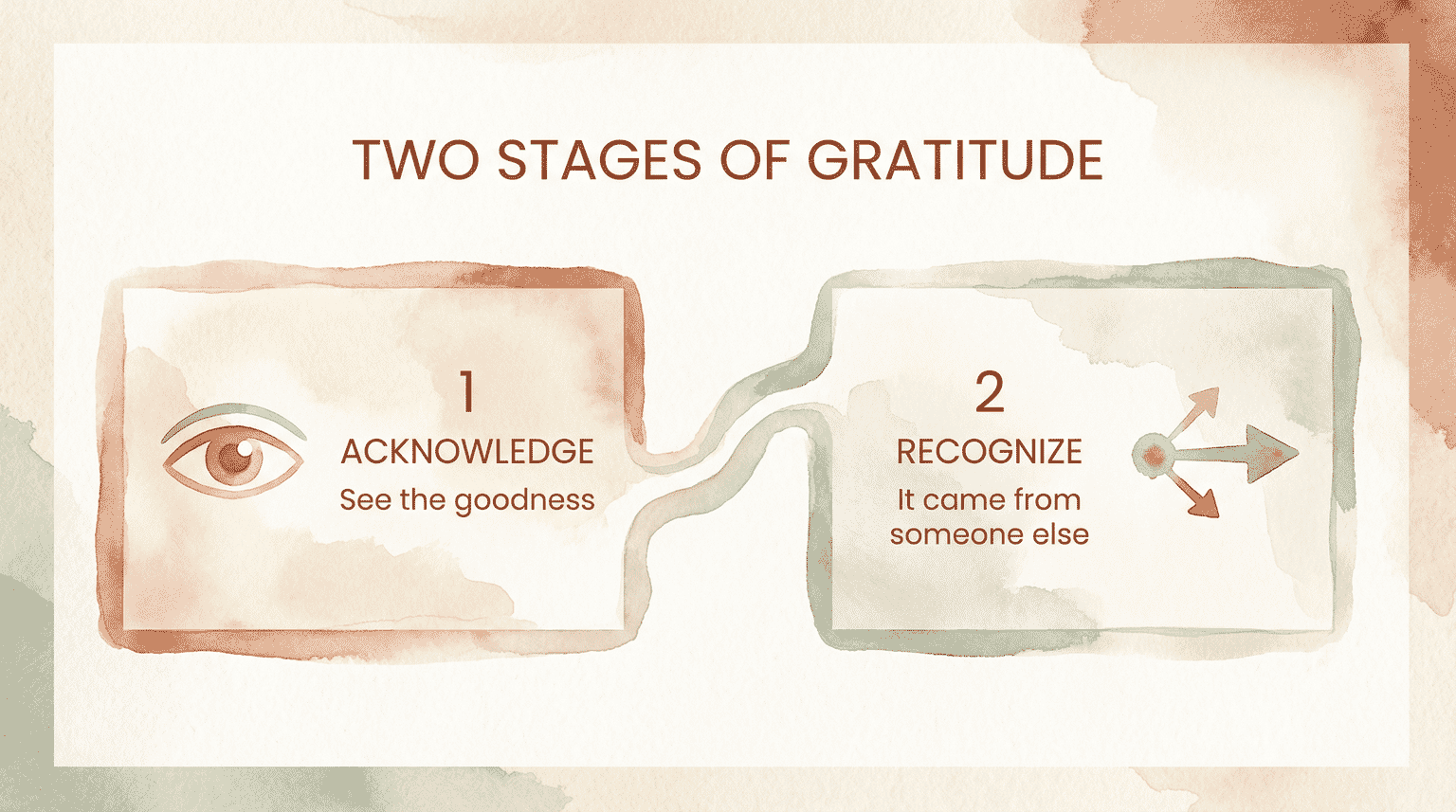

Here’s what my librarian brain needed to accept: gratitude isn’t an automatic response. It’s a trainable skill—even when kids have everything. Dr. Robert Emmons, a leading gratitude researcher, identifies two stages in genuine gratitude: acknowledging goodness and recognizing that its source lies outside oneself. Both require cognitive development and practice.

Try role-playing disappointing gifts at home:

“Pretend I gave you socks for your birthday. What would you say?”

This works especially well for children 5 and up. Make it silly—pretend to gift a banana or a single crayon. Practice finding something true to say: “Thank you! I’ve never gotten a banana before!”

For younger children, simple modeling works better: “We always say thank you when someone gives us something, even if we’re not sure about it yet.”

Research on grateful youth shows that children who develop gratitude skills demonstrate lower materialism and higher prosocial behaviors. You’re not just teaching manners—you’re building a character trait that will serve them across their entire lives.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does my child act ungrateful about gifts?

They’re not ungrateful—they’re experiencing what psychologists call the “backfire condition,” where gratitude and disappointment coexist naturally. Research confirms this is a normal response to receiving something that doesn’t match expectations, not a character defect.

What should a child say when they don’t like a gift?

Coach them toward phrases that acknowledge the giver without lying: “Thank you for thinking of me!” or “Thank you! Can you tell me why you picked this?” These express genuine appreciation for the effort while avoiding false enthusiasm about the object.

How do you handle gift disappointment in front of family?

Stay calm—your reaction sets the tone. Whisper a quick prompt if needed, then redirect attention to the giver. Save the feelings conversation for later, privately. Gift-givers feel rejection as strongly as physical pain, so protecting the relationship takes priority in the moment.

Is it okay for kids to feel disappointed about gifts?

Absolutely. Disappointment doesn’t cancel out gratitude—both emotions naturally coexist. The goal isn’t eliminating disappointment but teaching children they can feel let down AND still express appreciation for the giver’s thoughtfulness.

How do you teach gratitude without forcing it?

Practice before gift-giving events, not just after disappointment strikes. Role-play scenarios at home and focus conversations on the giver’s intention rather than the object itself. Gratitude researchers confirm it strengthens with awareness and practice over time.

Join the Conversation

How have you handled the disappointing-gift-in-front-of-the-giver moment? I’d love to hear both what you said to your child AND how you smoothed things with the gift-giver. These real-time saves are gold.

I read every comment because these moments teach us all.

References

- Mixed emotional variants of gratitude – Research on the “backfire condition” and coexisting emotions

- Givers’ feelings of social exclusion in gift failures – How gift rejection affects givers neurologically

- Incongruent affect in early childhood – Children’s developmental capacity for emotional display management

- Stronger together: Perspectives on gratitude – Gratitude development in adolescence

- What is gratitude and why is it so important? – Dr. Emmons’ two-stage gratitude framework

Share Your Thoughts