Your child ripped through six birthday presents in under ten minutes. Three weeks later, you find most of them shoved under the bed, barely touched. Meanwhile, she still talks about that afternoon you spent making friendship bracelets together last summer—an activity that cost you nothing.

Here’s the thing: this isn’t about being ungrateful or spoiled. It’s about how the brain actually encodes memories. And once you understand the mechanisms at work, you can make any gift—whether it’s a $100 toy or a $5 experience—far more likely to become a permanent memory.

Key Takeaways

- Three brain mechanisms determine whether gifts become lasting memories: emotional encoding, identity integration, and resistance to hedonic adaptation

- Children under 6 actually prefer material gifts, but by adolescence, experiences outperform possessions for lasting happiness

- The four markers of memorable gifts: special, unexpected, relationally significant, and creates a sense of feeling lucky

- How you give matters as much as what you give—anticipation, presence, and reminiscing afterward all strengthen memory formation

The Three Mechanisms That Determine What Sticks

My librarian brain couldn’t let this question go: why do some gifts become treasured memories while others essentially vanish? After digging through the developmental research, I’ve identified three distinct mechanisms that determine whether a gift becomes a lasting memory or fades within weeks.

These aren’t gift categories or age recommendations—they’re processes happening in your child’s brain. Understanding them gives you transferable knowledge that works for any gift, any occasion, any child.

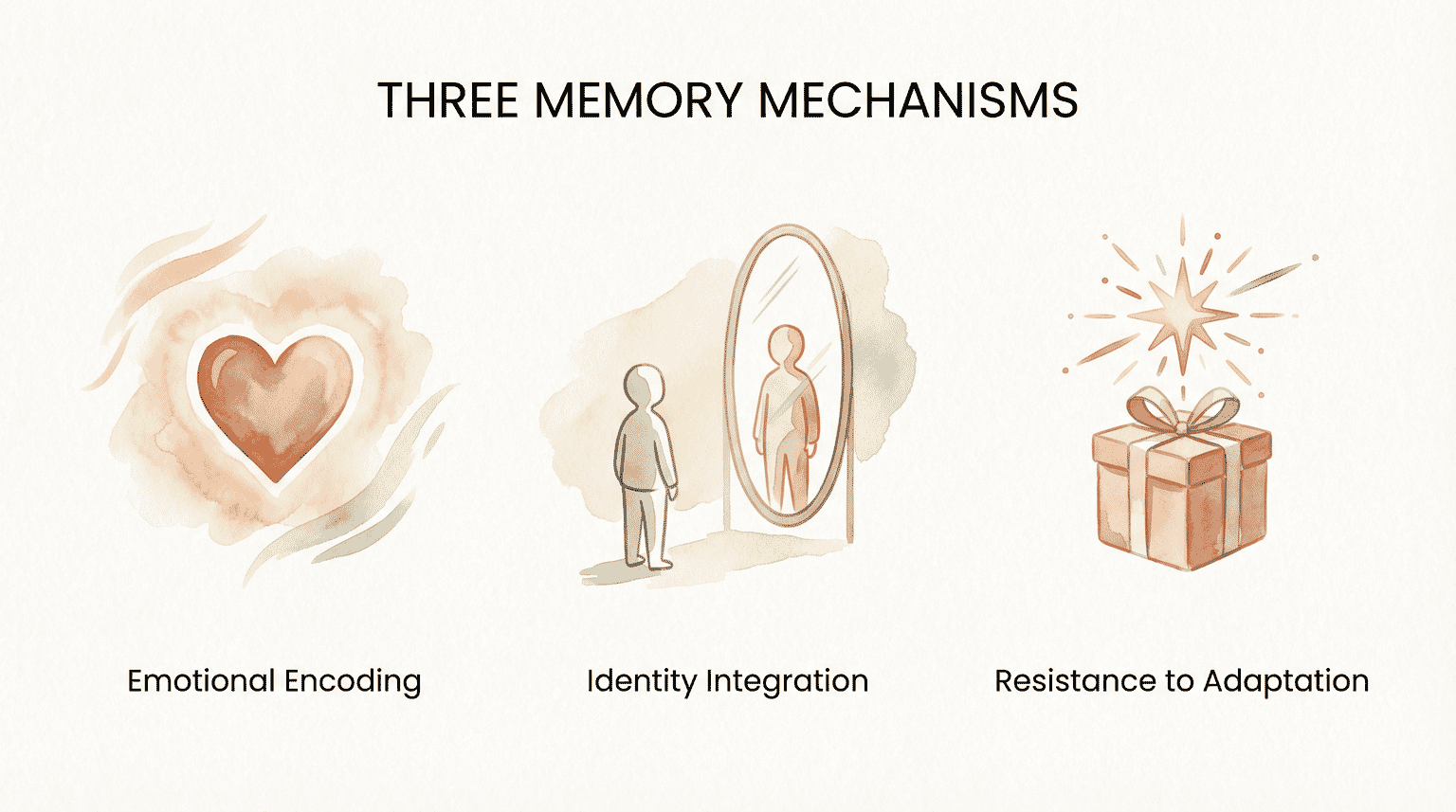

The three mechanisms:

- Emotional encoding—how feelings during the gift experience strengthen memory traces

- Identity integration—why some gifts become “part of who I am” while others stay external

- Resistance to hedonic adaptation—what makes certain gifts immune to the “novelty wore off” effect

Let’s break each one down.

Mechanism #1: Emotional Encoding

When your child experiences strong emotion during a gift moment—surprise, joy, anticipation, connection—their brain essentially tags that memory as “important, keep this one.”

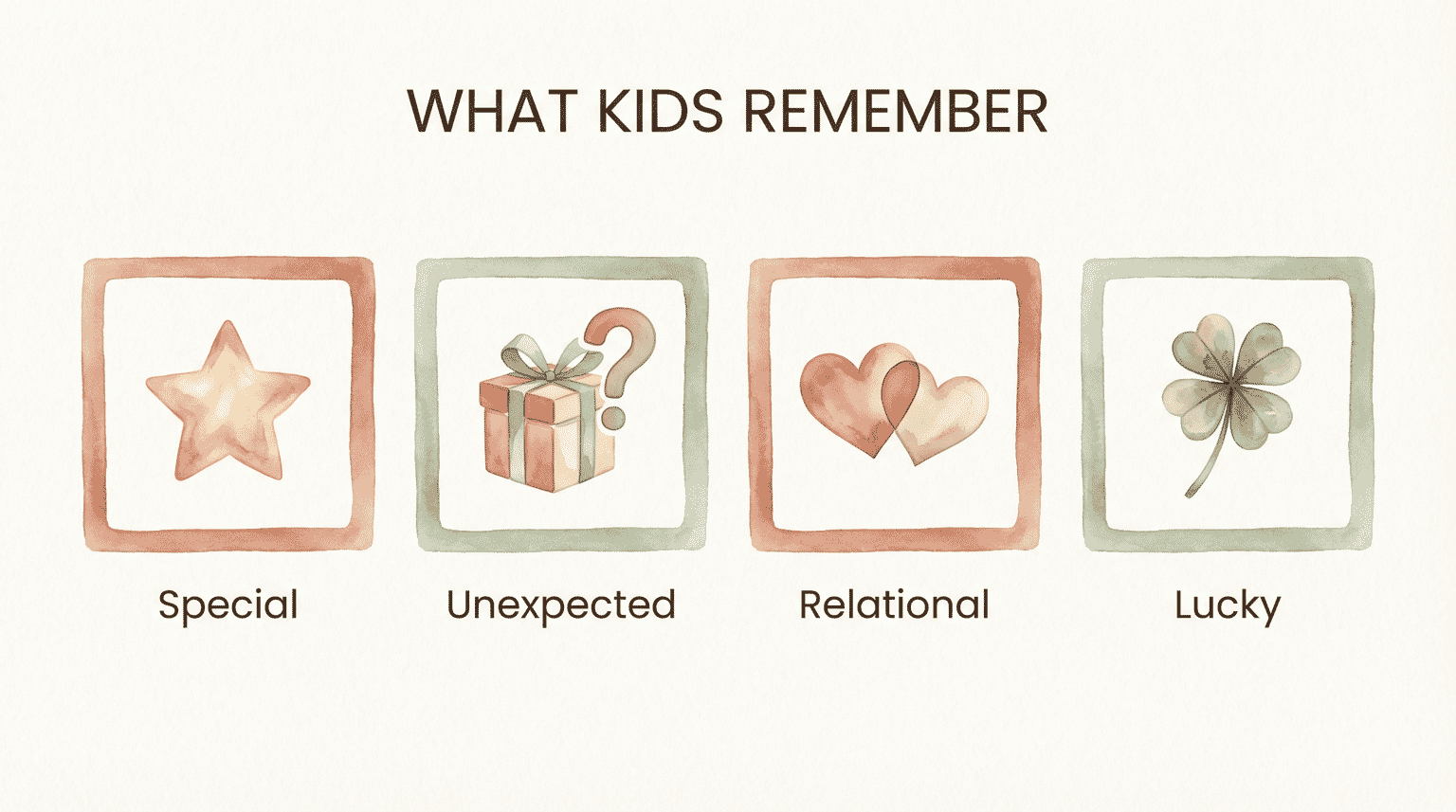

Research published in PMC (2022) identified four markers that predict whether children will remember a gift as meaningful:

“Children remember gifts that feel: special or enjoyable, unique or unexpected, relationally significant—it makes the giver happy too, and lucky—they feel fortunate to have it.”

— PMC Research on Childhood Gratitude, 2022

Notice what’s not on this list: price tag, brand name, or how many gifts they received.

In my house, I’ve watched this play out eight times now. My 12-year-old still talks about the year she got a simple journal with a letter inside explaining why I thought she was ready to record her own story. It hit all four markers—special, unexpected, relationally significant (I cried writing it), and she felt lucky.

Meanwhile, the more expensive gifts from that same birthday? She couldn’t tell you what they were.

The emotional encoding mechanism explains why how you give matters as much as what you give.

Mechanism #2: Identity Integration

Here’s where the research gets fascinating. A peer-reviewed study from PMC (2021) found that experiential purchases connect more closely to a person’s sense of self than material possessions. Experiences become “part of who I am,” while possessions remain psychologically external—things I have rather than things I am.

This explains something I’d noticed for years: my kids retell stories about experiences endlessly, but they almost never talk about possessions. The family camping trip where the tent collapsed? Still comes up at dinner. The expensive toy from that same year? Crickets.

Researchers call this “conversational value”—experiences give us stories to tell, and retelling strengthens memory. Every time your child recounts an experience to grandma, a friend, or even their stuffed animals, they’re reinforcing that neural pathway.

Material gifts, by contrast, offer limited conversational value. There’s only so much to say about a toy beyond “I have it.”

This mechanism has practical implications for gift selection. Gifts children make themselves carry special memory weight precisely because the creation process becomes part of the child’s identity story—”I made this.” The effort and intention get woven into who they are.

Mechanism #3: Resistance to Hedonic Adaptation

You’ve witnessed hedonic adaptation in action: that toy your child had to have becomes invisible within weeks. What psychologists call “hedonic adaptation” is the brain’s tendency to return to baseline happiness after acquiring something new.

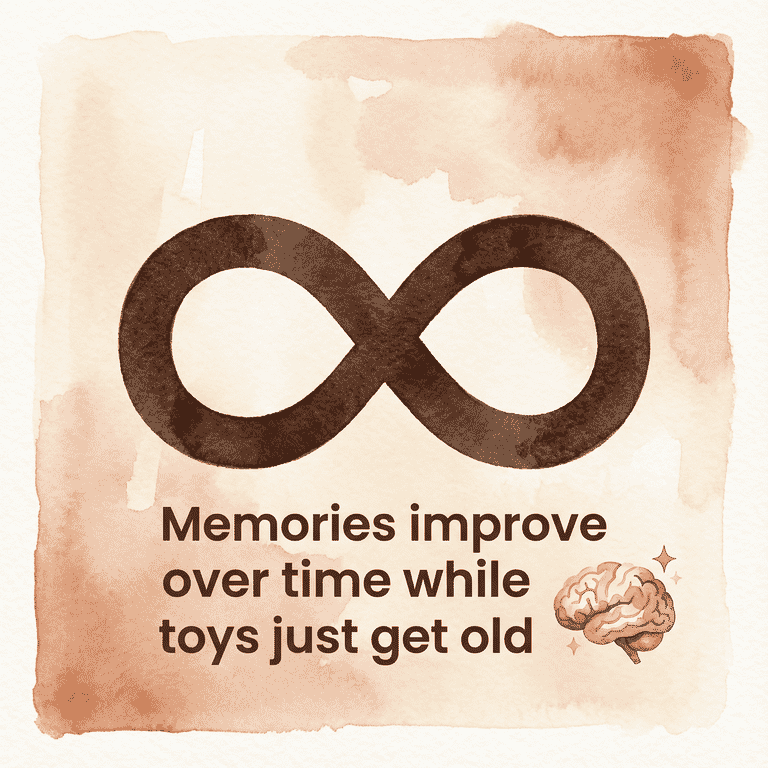

Here’s what memory researchers discovered: experiences are largely immune to this effect.

Why? Two reasons.

First, you can’t get “used to” a memory the way you can a possession. A toy sits there, becoming increasingly familiar. But a memory exists only when you recall it—and each recall is a fresh experience.

Second, memories actually improve over time. Researchers found that consumers engage in more active, positive memory construction for experiences than possessions.

Your brain smooths rough edges, highlights peak moments, and essentially edits the experience into an increasingly positive narrative. That camping trip with the collapsed tent? The misery fades while the adventure intensifies.

Possessions don’t get this treatment. They just get old.

As one PMC study noted, the value of meaningful items “extends beyond the physical objects, encompassing creativity, emotional connection, family connections, and cultural identity.” When a physical gift carries these qualities, it becomes more like an experience—and gains some resistance to adaptation.

The Cognitive Sophistication Threshold

Here’s where I need to add an important caveat: everything I’ve said about experiences outperforming material gifts has an age-related catch.

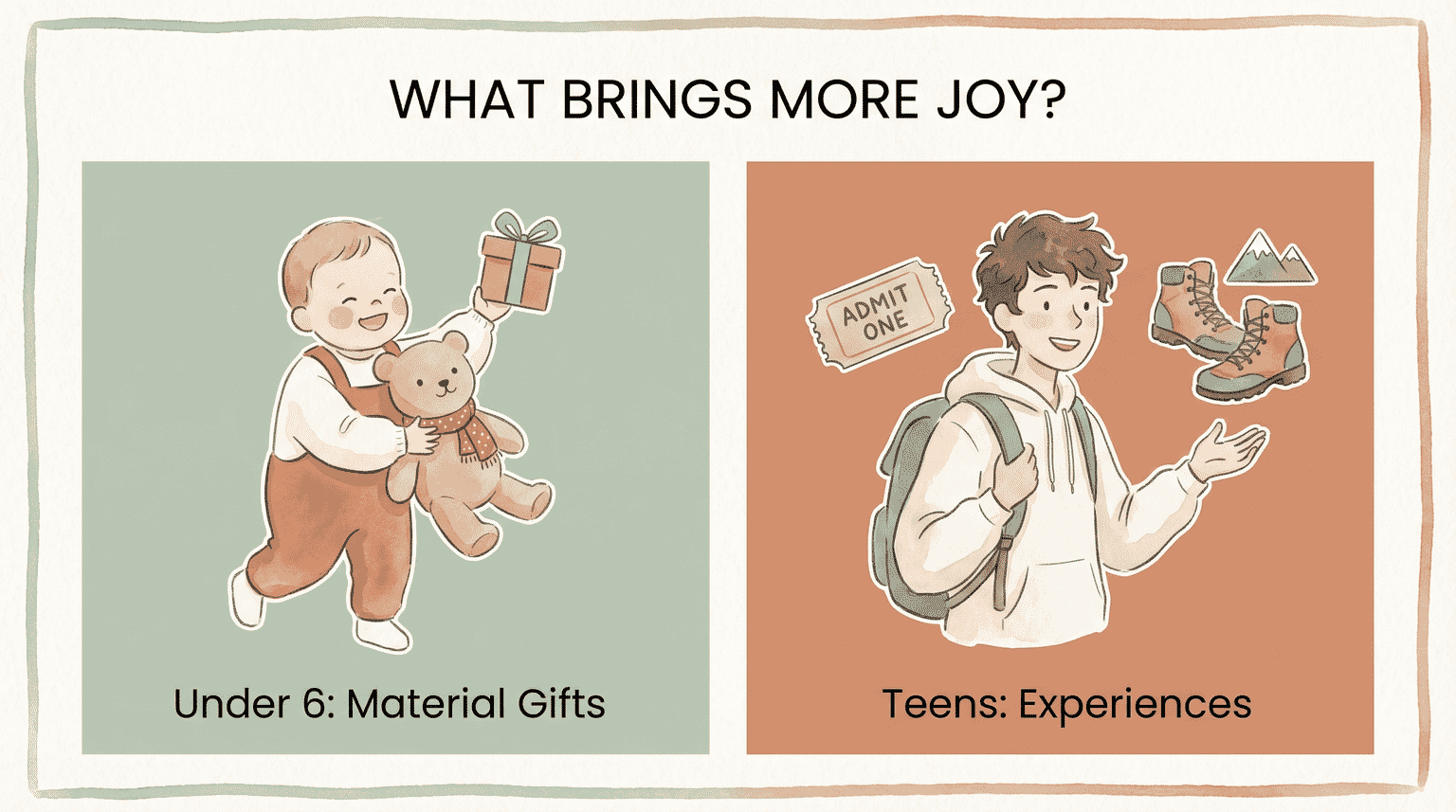

University of Chicago professor Lan Nguyen Chaplin found something that surprised many parents: children under 6 actually derive more happiness from material gifts than from experiences.

Why? As Chaplin explains:

“An experience is much more complex than a material good. Experiences are abstract, difficult to compare, and involve social interactions. To fully appreciate and derive happiness from experiences, children require cognitive sophistication.”

— Lan Nguyen Chaplin, PhD, University of Chicago

Young children’s memory systems are still developing. Research shows children form explicit memories with contextual details starting around 26 months, but episodic memory—the ability to recall specific events—develops substantially between ages 3 and 4. By age 5, children can reliably use memories to anticipate future experiences.

What does this mean practically? For toddlers and preschoolers, tangible gifts they can hold, manipulate, and see right now often work better than abstract experiences they’ll need to remember later.

But here’s the twist: by adolescence, Chaplin’s research shows the pattern reverses completely. Experiences outperform possessions for lasting happiness.

For a detailed age-by-age breakdown of how children process gifts at different developmental stages, see our complete guide to the science behind meaningful gifts.

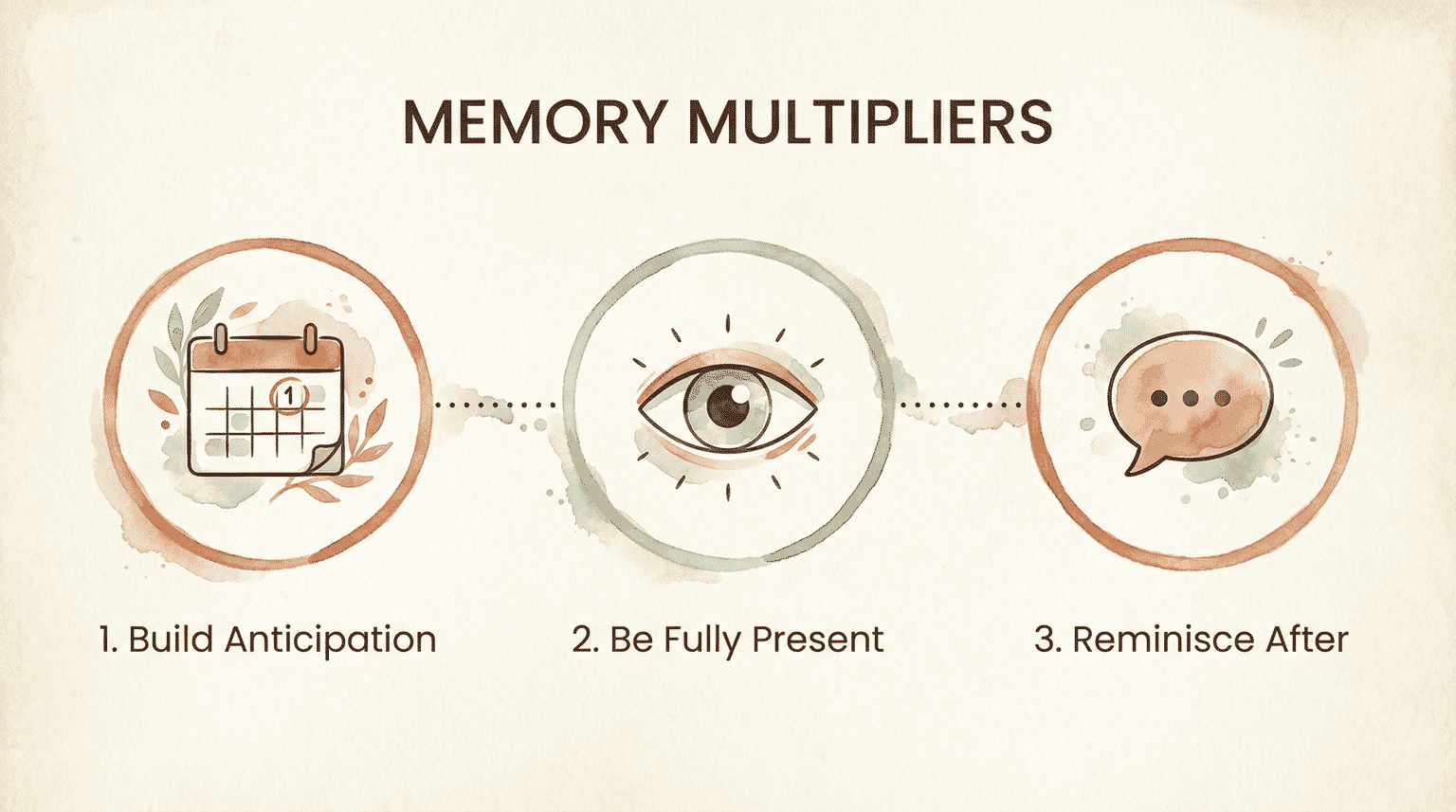

Memory Multipliers: Making Any Gift Stick

Now for the practical part. Regardless of what you’re giving, three strategies amplify the memory-forming potential.

Before: Build Anticipation

UC Davis researchers discovered that U.S. children waited nearly four times longer for gifts than for food—suggesting gift-giving occasions carry special psychological significance that builds anticipation tolerance.

This isn’t just patience training. Anticipation primes the brain for memory encoding. When your child spends days looking forward to something, they’re essentially pre-loading emotional significance onto that future moment.

Try this: For birthday gifts, start counting down a week ahead. For experiences, talk about what you’ll see, do, and feel. The waiting isn’t torture—it’s memory prep.

During: Be Fully Present

Shared attention during gift moments matters enormously. When you’re physically present but mentally scrolling through your phone, you’re missing the relational significance that makes gifts memorable.

Amy Lopez, PhD, from University of Colorado School of Medicine, notes that gift-giving creates “empathetic joy”—sharing in another’s happiness. That shared emotional moment is precisely what strengthens memory encoding for both giver and receiver.

Try this: Put the phone away. Make eye contact. Ask questions. Your attention tells your child’s brain “this moment matters.”

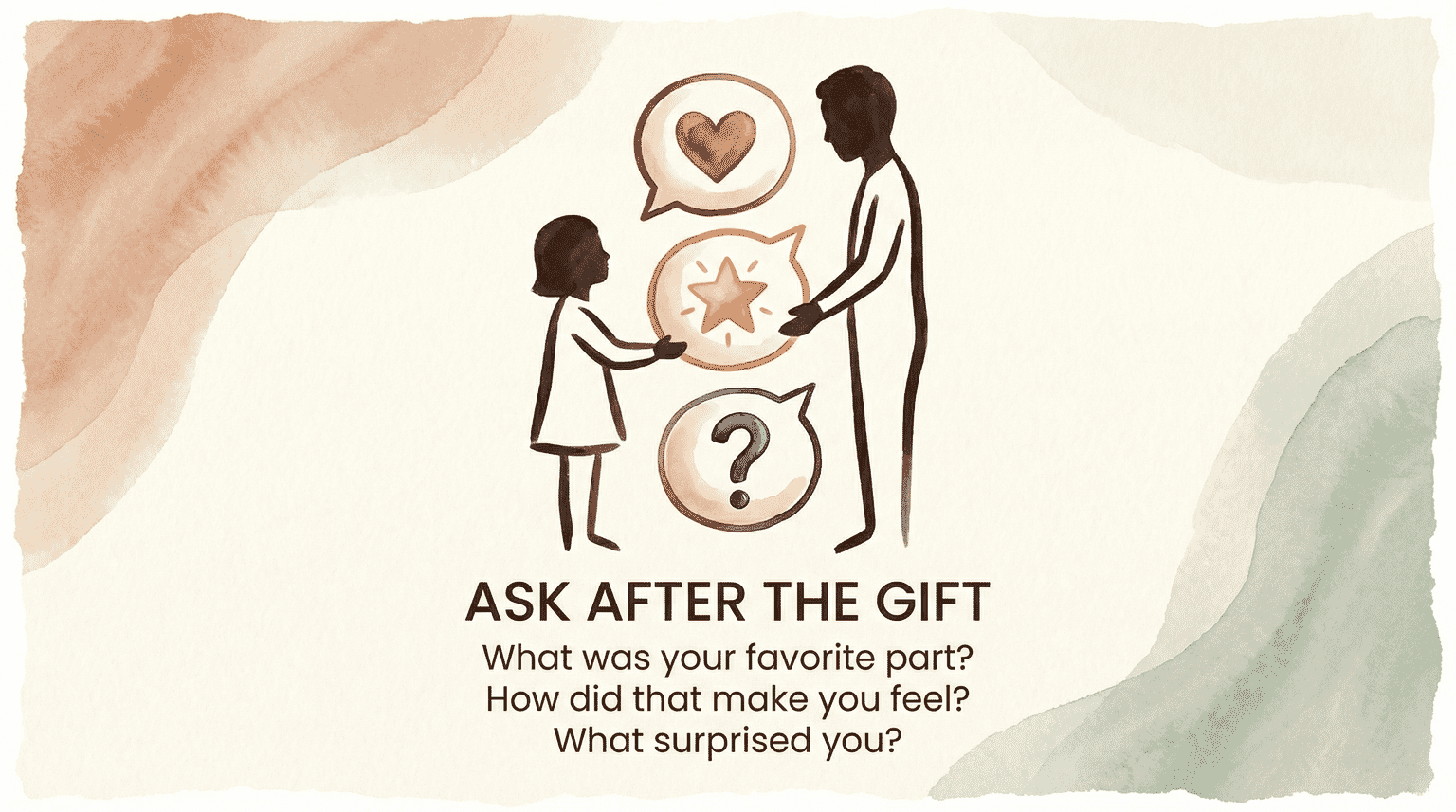

After: Elaborative Reminiscing

Developmental psychologists have documented the power of what they call “elaborative reminiscing”—the conversations after an experience that cement it into long-term memory.

This isn’t just asking “Did you like it?” It’s asking:

- “What was your favorite part?”

- “How did that make you feel?”

- “What surprised you?”

- “What would you want to do differently next time?”

These questions prompt your child to reconstruct the memory actively, strengthening neural pathways each time.

When your child receives a gift: Instead of moving immediately to the next present, pause and ask: “What do you think you’ll make with this first?” or “What made you want this one?”

Research found that parent-child conversations about past events may be more beneficial than in-the-moment discussions because temporal distance decreases emotional intensity, allowing children to better encode the lessons and meanings.

What Undermines Memory Formation

Understanding the mechanisms also reveals what works against lasting memories.

Too many gifts at once. When children open gift after gift in rapid succession, they can’t emotionally encode any single one deeply. The research on choice overload applies here: shallow engagement with many items beats deep engagement with few.

Fewer toys, more creative play. Here’s a counter-intuitive finding that surprised me: research on childhood toy memories found that children with fewer toys played more creatively, and simple toys requiring imagination were remembered more fondly than elaborate ones. Too many toys can actually stifle creativity and meaningful attachment.

Pre-programmed experiences. Toys that dictate exactly how to play leave little room for the child’s own creativity and imagination—the very elements that make memories personal and lasting.

Missing the four markers. If a gift doesn’t feel special, isn’t unexpected, lacks relational significance, or doesn’t create a sense of feeling lucky, it’s working against the memory-forming mechanisms.

Creating Gift Rituals

Finally, rituals create what memory researchers call “retrieval cues”—pathways that make memories easier to access and stronger over time.

In my house, we’ve developed traditions that make even simple gifts more memorable:

- Birthday breakfasts with decorations they wake up to

- One “experience gift” per child at Christmas, opened last

- Annual photo recreations of past gift moments

- A memory jar where we write down gift-related moments throughout the year

Physical artifacts from experiences—photos, ticket stubs, small souvenirs—serve as retrieval cues that trigger memory networks when children encounter them. These don’t need to be expensive; a rock from a special hike works as well as any souvenir.

The traditions themselves become part of the memory. My teenagers, who roll their eyes at most things, still get excited about our annual gift traditions—because those rituals have been encoding positive memories for over a decade.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do kids forget toys so quickly?

Children’s brains experience hedonic adaptation—the process where excitement from possessions fades as they become familiar. Unlike experiences, toys remain external to a child’s sense of self, making them easier to mentally discard. They also offer limited “conversational value,” meaning children rarely retell stories about possessions.

Do kids prefer toys or experiences?

It depends on age. Research found children under 6 derive more happiness from material gifts because experiences require cognitive sophistication to appreciate. By adolescence, this reverses—experiences outperform possessions for lasting happiness and memory formation.

What makes a gift meaningful to a child?

Gratitude research identified four markers: the gift feels special or enjoyable, it’s unique or unexpected, it has relational significance (makes the giver happy too), and it creates awareness of good fortune. Gifts meeting multiple markers are most likely to become permanent memories.

How do I make gifts more memorable for kids?

Focus on three phases: build anticipation beforehand (waiting strengthens encoding), be fully present during the moment (shared attention deepens memory), and use elaborative reminiscing afterward—asking open-ended questions about feelings and favorite parts. These conversations cement memories for years.

Over to You

What gift does your child still talk about years later? I bet it’s not the most expensive one. Mine remember a $3 glow-in-the-dark treasure hunt more vividly than any “big” present. I’d love to hear which gifts actually stuck—and what you think made them memorable.

Your stories help me understand what really creates lasting memories.

References

- What Makes Children Happier? Material Gifts or Experiences? – University of Chicago research on developmental shifts in gift preferences

- What Parents and Children Say When Talking about Gratitude – PMC research on the four markers of memorable gifts

- More Experience, Less Loneliness? – PMC research on experiential vs. material purchases and identity integration

- Toys from Childhood in Immigration: Placing Memories – PMC research on toy memories and creative play

- Two-Year-Olds Use Past Memories – PMC research on early memory development

- Embrace Giving This Holiday Season – University of Colorado research on gift-giving psychology

- How Children React to Waiting in Different Cultures – UC Davis research on anticipation and delayed gratification

Share Your Thoughts