Your 6-year-old just ripped through eight presents in four minutes. Now she’s asking “Is that all?” Meanwhile, her 2-year-old brother is happily sitting inside a cardboard box, ignoring everything else. And your teenager hasn’t looked up from the one gift card she actually wanted.

Here’s the thing: every single one of these reactions is exactly what their brains are supposed to do.

My librarian brain couldn’t let this go without investigating. After eight kids spanning ages 2 to 17—and watching roughly 1,200 gifts get opened, played with, ignored, treasured, or immediately abandoned—I started digging into the actual neuroscience. What I found completely changed how I think about gifts, gratitude, and what we should realistically expect from our kids at each age.

Key Takeaways

- Children’s brains process gifts differently at each developmental stage—the toddler ignoring expensive toys for the box is doing exactly what their brain is wired to do

- Theory of Mind develops between ages 3-7, which is when genuine gratitude becomes neurologically possible

- Gift experiences release dopamine, oxytocin, and serotonin—the same chemicals triggered by food and survival-essential experiences

- Limiting gifts actually increases appreciation by preventing the “hedonic treadmill” effect

- The relational context of a gift matters more than its cost—presence and attention create stronger neural memories than expensive items given distractedly

What’s Actually Happening in the Brain

When your child receives a gift they love, their brain launches a chemical cascade that’s been evolving for thousands of years. According to the American Psychological Association, gift-giving activates brain regions associated with pleasure, social connection, and trust—the same neural circuits triggered by food and other survival-essential experiences.

Three key chemicals drive the experience:

- Dopamine: The “wanting” chemical that creates pleasure and anticipation

- Oxytocin: The bonding hormone that signals trust, safety, and connection

- Serotonin: The mood regulator that contributes to overall well-being

The neuroscience of giving reveals something unexpected about how our brains process these moments.

“Oftentimes, people refer to it as the ‘warm glow,’ this intrinsic delight in doing something for someone else. But part of the uniqueness of the reward activation around gift-giving… is that because it is social it also activates pathways in the brain that release oxytocin… It’s often referred to as the ‘cuddle hormone.'”

— Emiliana Simon-Thomas, PhD, Science Director at UC Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center

Here’s what surprised me most in the research: the entire gift experience—from shopping to wrapping to anticipating the reaction—activates reward pathways. This explains why my 8-year-old checks the package tracking app obsessively. Her brain is getting dopamine hits from the anticipation itself, not just the final unwrapping.

And crucially, receiving a well-matched gift from someone who loves you creates a nearly identical neural response to giving one. When your child opens something they genuinely wanted from someone they genuinely love, they’re experiencing the same oxytocin-mediated reward you felt choosing it.

How Children’s Brains Develop (The Foundation You Need)

Before diving into specific ages, here’s the foundational science that explains why kids respond so differently to gifts at different stages.

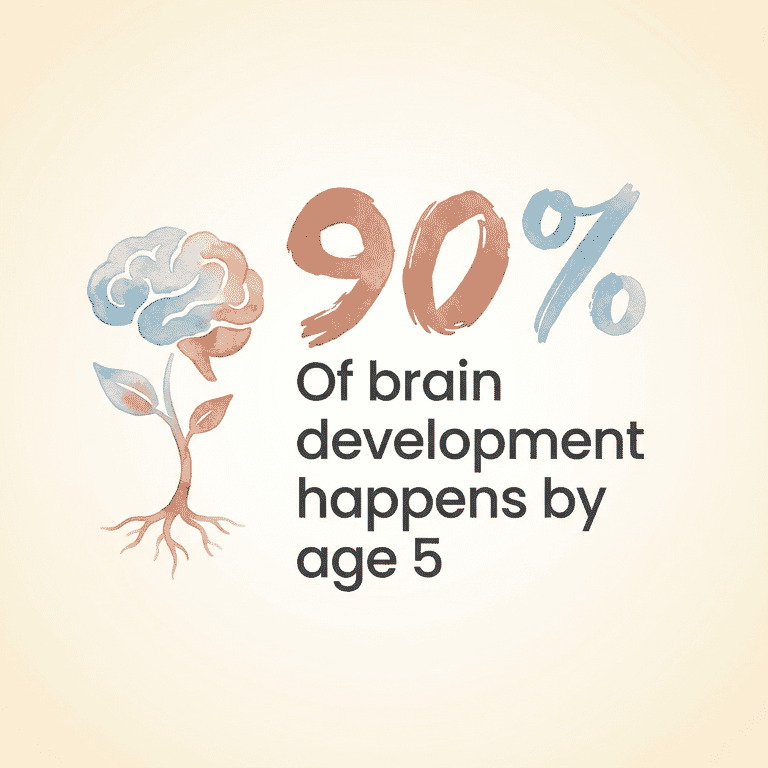

Research from Lurie Children’s Hospital reveals a staggering statistic: more than one million neural connections form every second in the first years of life. By age 5, roughly 90% of brain development is complete.

This explosive neural growth explains why early experiences matter so much. Every interaction—including gift-giving moments—becomes part of the environmental input shaping their brain architecture.

But here’s what matters for gift-giving: the brain develops from back to front. The visual processing areas mature first, while the prefrontal cortex develops last.

This back-to-front pattern explains almost everything frustrating about kids and gifts:

- Why toddlers can’t appreciate that something cost more

- Why preschoolers struggle with delayed gratification

- Why elementary kids fixate on fairness

- Why teens can reason about gifts but still act impulsively

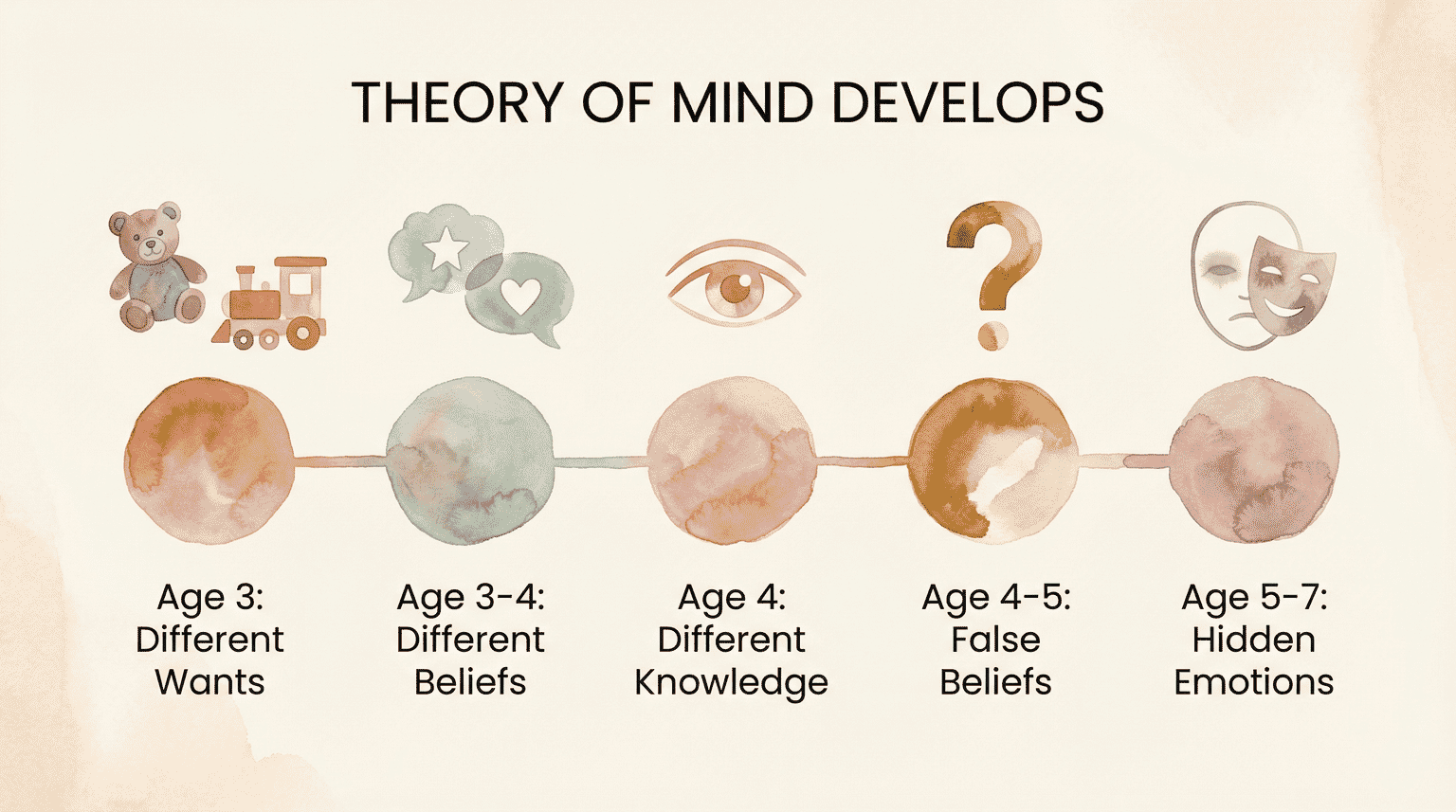

The other critical framework is Theory of Mind—the developmental progression documented by MIT researchers that describes how children learn to understand others’ thoughts and intentions. This unfolds in a predictable sequence:

- Diverse Desires (age 3): Understanding that others want different things than they do

- Diverse Beliefs (age 3-4): Grasping that others can believe different things

- Knowledge Access (age 4): Recognizing that others might not know what they know

- False Belief (age 4-5): Understanding that others can believe things that aren’t true

- Hidden Emotion (age 5-7): Realizing people can feel differently than they appear

This sequence directly affects when children can genuinely appreciate that someone thought about them, made sacrifices for them, and chose something specifically for them. In other words: when genuine gratitude becomes neurologically possible.

Ages 0-2: The Sensory Explorers

What’s happening in the brain: Synapses are forming at that million-per-second rate. Sensory processing dominates everything. The prefrontal cortex—which would allow value assessment—is barely online.

What you’ll see with gifts: Your baby or toddler cannot assess monetary value. This isn’t willfulness; it’s architecture. Their brains are wired for novelty and sensory exploration, which means the cardboard box genuinely offers more neurological reward than the expensive toy inside it.

Research from Stanford’s Neurosciences Institute shows that infant brains have significant organization from birth but retain substantial flexibility for learning through experience. Early gift experiences—whether a crinkly book or a simple stacking toy—become part of the environmental input shaping their neural architecture.

Gift-giving capacity: Here’s something beautiful I’ve witnessed with all eight of my kids. Research confirms that infants as young as 12-18 months spontaneously share food or toys with parents and strangers. This isn’t trained behavior—it’s an innate prosocial impulse. When your toddler offers you a soggy cracker, their brain is doing exactly what it evolved to do.

What parents should expect: The box being more interesting than the gift is completely normal—even developmentally optimal. Your under-2 is doing sophisticated work: exploring texture, testing gravity, discovering cause and effect. The $80 toy that does one thing can’t compete with a box that can be opened, closed, climbed in, pushed across the floor, or worn as a hat.

Gratitude capacity: Pre-verbal children express appreciation through engagement, not words. When your 18-month-old squeals and immediately starts manipulating a new toy, that IS their gratitude response. Expecting verbal thanks is like expecting them to appreciate the stock market.

Ages 3-5: Theory of Mind Awakens

What’s happening in the brain: This is when things get fascinating. Theory of Mind is emerging, which means your preschooler is beginning to understand that other people have different thoughts, desires, and knowledge than they do.

What you’ll see with gifts: Around age 3-4, children start grasping that the gift-giver intended to make them happy. This is huge. Before this stage, a gift was simply an object appearing. Now it’s connected to a person’s mind.

The five-step developmental sequence means 3-year-olds typically understand diverse desires (“Grandma knew I wanted this!”) before they can handle false beliefs. By 4-5, most children pass classic false-belief tests, understanding that someone can believe something that isn’t true—a prerequisite for sophisticated social navigation around gifts.

Gift-giving capacity: Preschoolers can now predict what others might want. Research found that children who passed Theory of Mind tasks were 10.6 times more likely to engage in strategic social behavior. In my house, this is when kids started picking out “special” gifts for siblings rather than choosing what they wanted to give.

That said, actual sharing rates remain low. Studies show preschoolers share under 6% of resources when personal cost is evident. Your 4-year-old who picked out a present for a friend but won’t share her own birthday toys? Developmentally normal.

What parents should expect: Preschoolers are navigating new cognitive territory. They understand someone chose this for them but may not fully grasp the effort or sacrifice involved. Prompted thank-yous are appropriate but forced effusiveness isn’t neurologically supported yet.

Gratitude capacity: We’re moving from trained response toward emerging genuine appreciation. A 5-year-old who says “Grandma got this because she remembered I like dinosaurs!” is demonstrating real Theory of Mind in action—connecting the gift to the giver’s knowledge and intention.

Ages 6-8: The Fairness Processors

What’s happening in the brain: The prefrontal cortex is gaining strength. Delayed gratification is improving (though still inconsistent). Most significantly for gift situations, the brain is now intensely focused on fairness and social comparison.

What you’ll see with gifts: If you have multiple children, you already know this stage intimately. The 7-year-old who counts presents. The 6-year-old who notices her sister got “more.” The 8-year-old who calculates rough equivalence across gifts.

This isn’t greed—it’s the brain’s fairness processors coming online. Children this age are developing sophisticated mental accounting for social equity. When my kids were this age, Christmas morning occasionally required a calculator and a calm explanation of why experiences and objects don’t compare directly. Building family gift traditions helps create shared expectations that reduce these comparisons.

Gift-giving capacity: Now empathy can drive gift selection. Children 6-8 can genuinely consider what the recipient would enjoy versus what they themselves want to give. They understand that knowing someone well helps you choose better gifts.

By this age, children can also pass the “hidden emotion” stage of Theory of Mind—understanding that people can feel differently than they appear. This means they can start to navigate socially complex gift situations: thanking Aunt Martha for the sweater even if they’re disappointed.

What parents should expect: Vocal fairness concerns. Comparison between siblings’ gifts. Questions about why someone got something specific. These are signs of healthy cognitive development, not character flaws.

Gratitude capacity: Children 6-8 can now understand effort and sacrifice behind gifts. They can genuinely appreciate that Dad took time to find this, or that Grandma spent money she could have used on herself. This is when gratitude-building conversations become neurologically meaningful.

Ages 9-12: The Abstract Thinkers

What’s happening in the brain: Abstract thinking is emerging. Social identity is forming. Peer influence on preferences is intensifying—sometimes dramatically.

What you’ll see with gifts: This is the age when gift preferences suddenly seem externally driven. The 10-year-old who wants exactly what his friend has. The 11-year-old who dismisses anything “babyish.” The 12-year-old whose entire wish list comes from social media.

In my house, this stage brought requests I’d never heard of for items that apparently “everyone” had. My librarian brain wanted to research these trends; my mom brain just wanted to understand why everything I’d chosen was suddenly wrong.

Gift-giving capacity: Children this age can plan genuinely thoughtful gifts. They understand symbolic meaning—that a gift can represent a shared memory, an inside joke, or a statement about the relationship. My tweens started giving each other gifts that referenced experiences only they understood.

Research from the Templeton Foundation confirms that even small acts of generosity activate the mesolimbic reward system. Tweens who experience this reward from giving are building neural pathways that support lifelong generosity.

What parents should expect: Desire for peer-approved gifts. Embarrassment about previously loved items. Seemingly sudden shifts in preferences. This is identity formation in action—exhausting but necessary.

Gratitude capacity: Genuine appreciation is fully possible now. Children 9-12 can understand complex sacrifices: that parents work to afford things, that grandparents live on fixed incomes, that gifts represent choices to spend resources this way rather than that way. They may still struggle to express it gracefully.

Ages 13-17: Approaching Adult Processing

What’s happening in the brain: Reward processing resembles adult patterns. The prefrontal cortex is more developed but still not complete—which explains the gap between teenagers’ sophisticated reasoning and occasional impulsive decisions.

What you’ll see with gifts: Research from Carnegie Mellon, featured on the Hidden Brain podcast, found a consistent pattern: gift givers focus on the “moment of exchange” while recipients focus on the long-term experience with the gift. Teenagers exemplify this—they may not react dramatically to unwrapping but will genuinely use and appreciate a well-chosen gift over time.

This age also shows a shift toward experiential preferences. Studies consistently find that experiences tend to bring more sustained happiness than material possessions at equivalent prices. My teenagers would rather have concert tickets than objects, dinner out with a friend than a new item.

Gift-giving capacity: Teenagers can give genuinely meaningful, relationship-building gifts. They understand nuance: that sometimes a small, perfect gift outweighs an expensive generic one. They can anticipate how someone will feel receiving something specific.

Understanding the deep human drive behind generosity helps explain why teens often become more giving-focused during these years.

“Giving isn’t just something on our to-do list. It’s something that’s a fundamental component of the human experience.”

— Elizabeth Dunn, Psychology Professor at the University of British Columbia

Teenagers are cognitively ready to experience this fully.

What parents should expect: Possibly muted immediate reactions (this doesn’t mean they’re ungrateful). Preference for experiences or gift cards that enable choice. Genuine thoughtfulness in gifts they give to others. The shift from receiving-focused to giving-focused pleasure often accelerates in these years.

Gratitude capacity: Adult-like appreciation is possible. Teenagers can understand sacrifice, effort, and intention at sophisticated levels. They can also, when emotionally regulated, express genuine thanks. When they don’t, it’s often about prefrontal cortex development lagging behind their intellectual understanding—they know they should express gratitude but struggle with execution.

The Four-Gift Rule: Why Science Says Limits Work

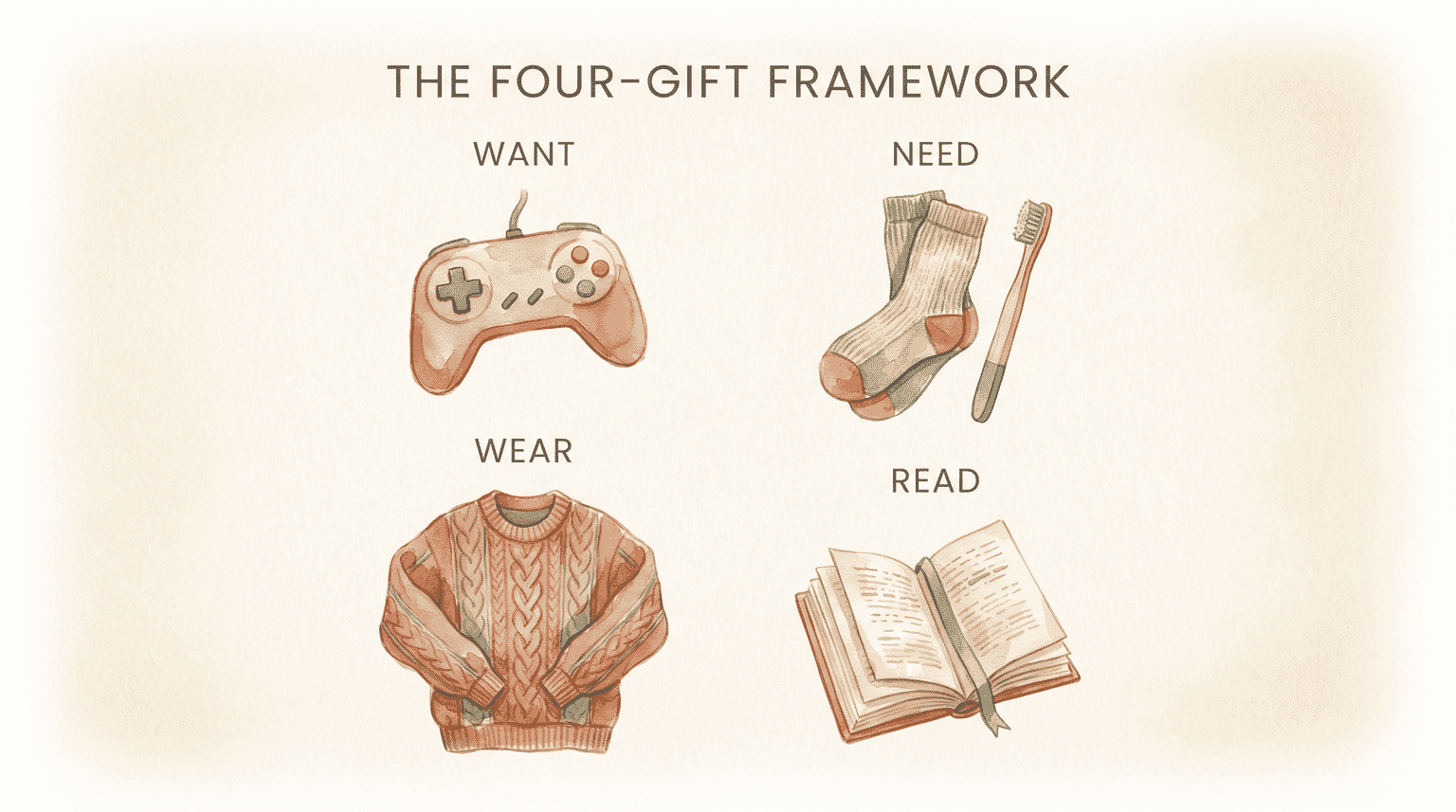

If you’ve heard of the “Something they want, something they need, something to wear, something to read” approach, here’s why it works at a neurological level.

The brain adapts to pleasure through a phenomenon researchers call the “hedonic treadmill.” More gifts don’t mean more happiness—they mean faster adaptation and less appreciation for each one.

“Try giving gifts that don’t do just one thing, so [the receiver] doesn’t get bored.”

— Sonja Lyubomirsky, Distinguished Professor of Psychology at UC Riverside

The four-gift framework naturally incorporates variety—different categories serving different needs—which keeps the brain engaged rather than adapted. It also prevents the overwhelm that leads to worse play outcomes.

In my house of eight kids, limits paradoxically created more joy. When everything is special, nothing is special. When four things are special, each one gets attention, exploration, and genuine appreciation.

Memory, Bonding, and Why Context Beats Cost

Here’s something that surprised me when I dug into the research: the neurological experience of a gift is shaped more by relational context than by the gift itself.

Elizabeth Dunn’s research reveals why:

“We see in our work that people are more likely to feel joy in giving when they can either directly observe or vividly imagine how their generosity is actually making a difference for the recipient… it’s important to bear witness to the delight of receiving.”

— Elizabeth Dunn, Psychology Professor at the University of British Columbia

This witnessing effect works both directions. When you watch your child open a gift, your brain releases oxytocin—the bonding hormone. When your child sees your excited anticipation, their brain incorporates that relational warmth into the gift memory.

This is why a small gift given with full presence and attention can neurologically outweigh an expensive gift given distractedly. The oxytocin-mediated bonding becomes part of the memory itself.

The broader impact of kindness and generosity shapes how we see our place in the world.

“It’s the warm glow effect. When we’re being kind or witnessing kindness, you kind of feel like we’re all in it together… we’re all human, all interdependent. You just feel good about the world.”

— Sonja Lyubomirsky, Distinguished Professor of Psychology at UC Riverside

Gift rituals—the traditions, the anticipation, the witnessing—create lasting neural associations that shape how children experience connection and generosity throughout their lives.

Practical Guidance for Parents

Age-Appropriate Gratitude Expectations

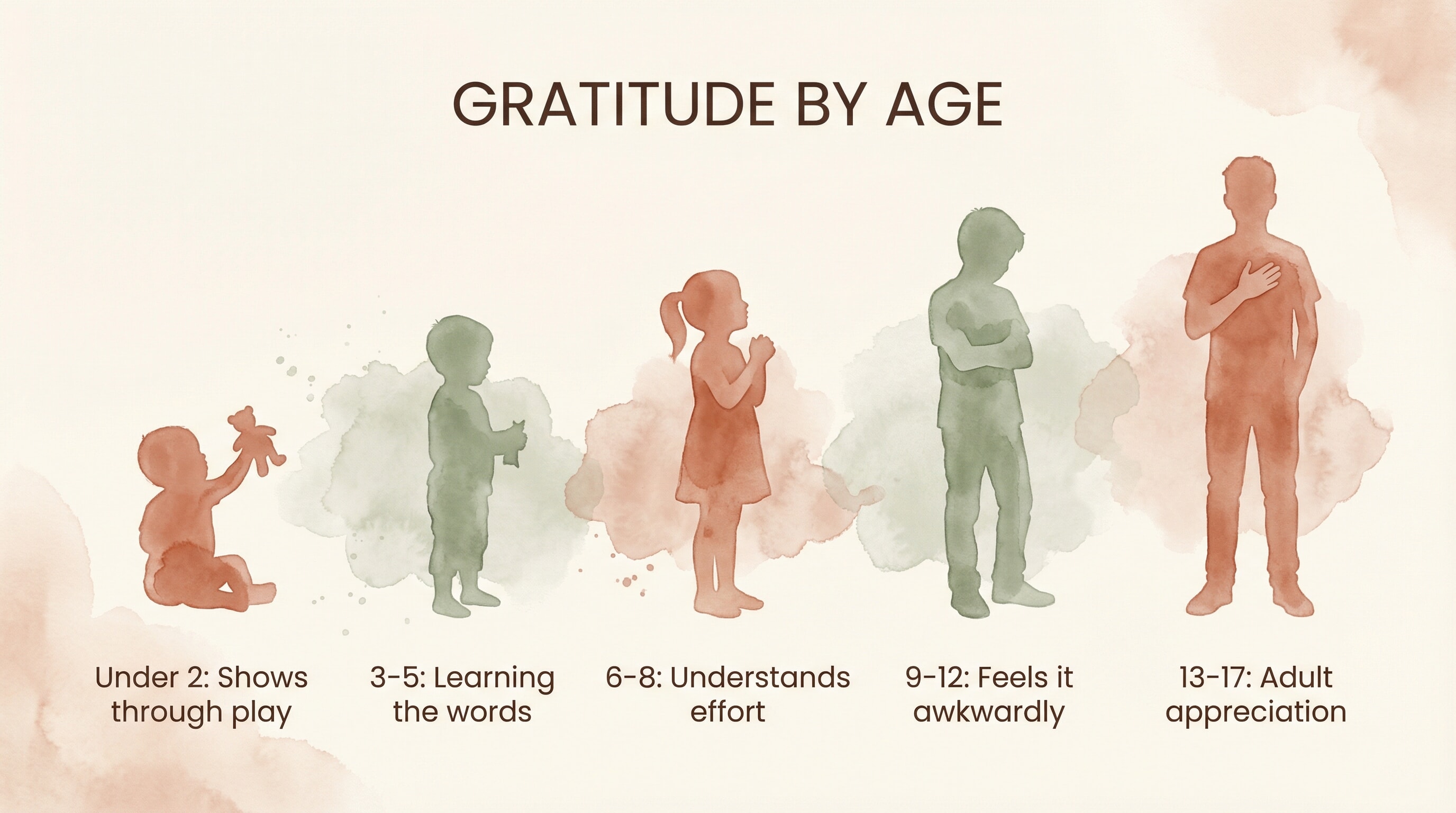

Based on the neuroscience, here’s what’s realistic:

- Under 2: Gratitude expressed through engagement, not words

- Ages 3-5: Prompted thank-yous are appropriate; genuine understanding emerging

- Ages 6-8: Can understand effort behind gifts; gratitude conversations are meaningful

- Ages 9-12: Genuine appreciation possible; expression may be awkward

- Ages 13-17: Adult-like appreciation; may need space before expressing it

When Children Seem Disappointed

First, remember that the prefrontal cortex—responsible for regulating emotional expression—isn’t fully developed. A disappointed reaction doesn’t mean your child is ungrateful; it means their brain hasn’t fully developed the capacity to manage and mask feelings.

When your child seems disappointed, try: “I notice you’re having a reaction to this gift. That’s okay—you can feel however you feel. Can you tell me about it?”

This approach acknowledges their emotional reality while opening a conversation. Later, when emotions have settled, you can discuss gratitude and effort without it feeling like punishment for having feelings.

If difficult gift situations arise, addressing them directly works better than forcing performed gratitude.

Preparing Children’s Brains for Gift Occasions

The anticipation itself activates reward pathways—use this intentionally:

- Talk about what gift-opening will feel like

- Discuss that some gifts might surprise them

- Role-play gracious responses beforehand (for socially complex situations)

- Set realistic expectations about quantity

Teaching Giving at Each Stage

Building gift-giving values happens developmentally:

- Toddlers: Notice and praise spontaneous sharing; don’t force it

- Preschoolers: Let them choose small gifts for others; discuss what the recipient likes

- Elementary: Involve them in choosing and wrapping; discuss why this gift fits this person

- Tweens: Support their independent gift-giving; discuss the experience afterward

- Teens: Give them budget and autonomy; share your own giving experiences

The Bottom Line

What I’ve learned from eight kids and hundreds of research papers is this: children’s brains are doing exactly what they’re supposed to do at each stage. The toddler ignoring the expensive toy for the box? Perfect sensory exploration. The 7-year-old counting presents? Fairness processors developing on schedule. The teenager underwhelmed on Christmas morning but genuinely using the gift for months? Age-appropriate reward processing.

Understanding the science hasn’t made gift-giving easier, exactly—I still have to navigate eight different developmental stages every December. But it has made it less frustrating. When I know why something is happening, I can meet my kids where they actually are instead of where I think they should be.

The research is clear that gift experiences—both giving and receiving—shape brain development in lasting ways. The oxytocin released during gift rituals builds attachment. The anticipation and surprise strengthen reward pathways. The experience of giving creates neural associations between generosity and well-being.

Every gift occasion is brain-building. And knowing that changes everything about how I approach them.

Frequently Asked Questions

At what age do children understand gift-giving?

Children begin understanding gift-giving in stages. By 12-18 months, infants spontaneously share. Around age 3-4, Theory of Mind emerges—the ability to understand that others have different wants. By age 5-6, most children grasp that givers have intentions and make sacrifices, enabling genuine appreciation rather than just excitement about receiving.

Why do toddlers not care about expensive gifts?

Toddlers’ brains cannot assess monetary value—their prefrontal cortex won’t fully develop until their mid-20s. Instead, toddler brains are wired for novelty and sensory exploration. A cardboard box offers more manipulation possibilities than an expensive toy, making it more neurologically rewarding.

Why does my child get more excited about the box than the gift?

This is developmentally normal, especially under age 3. Young brains are wired to seek novelty and sensory exploration. A box can be opened, closed, climbed in, decorated, or transformed—offering multiple interaction possibilities that sustain engagement longer than many single-purpose toys.

When can children feel genuine gratitude?

Genuine gratitude requires understanding that someone made an effort or sacrifice on your behalf—a cognitive ability developing alongside Theory of Mind. Most children begin developing this capacity around ages 5-7. Before this, children can learn to say “thank you” but may not neurologically experience the feeling adults recognize as gratitude.

Is it better to give children experiences or toys?

Research suggests experiences often provide longer-lasting happiness, partly because they don’t trigger the “hedonic treadmill” as quickly. However, the best approach depends on age: young children under 6 benefit from tangible items they can explore sensorially, while older children and teens often derive more sustained joy from experiential gifts.

What happens in a child’s brain when they receive a gift?

When children receive a desired gift, their brains release dopamine (creating pleasure), oxytocin (promoting connection with the giver), and serotonin (regulating mood). If the gift comes from someone the child loves and matches their desires, the neurological response can be as powerful as the “warm glow” adults experience when giving.

Join the Conversation

What’s something in this article that changed how you think about gifts? Or what question do you still have about how kids experience gift-giving? I’m constantly learning new things about this topic—and reader questions often spark future research dives.

Your insights help me understand what parents really want to know about kids’ brains.

References

- What Happens in Your Brain When You Give a Gift – American Psychological Association research on the neuroscience of gift-giving and the warm glow effect

- Brain Development in Early Childhood – Lurie Children’s Hospital on neural development milestones and the importance of early experiences

- Give Well, Feel Great: The Science of Gift Giving and Receiving – Templeton Foundation research on generosity and the mesolimbic reward system

- Theory of Mind – MIT Open Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science on the developmental sequence of understanding others’ minds

- Bridging Nature and Nurture: The Brain’s Flexible Foundation from Birth – Stanford research on how infant brains balance innate organization with experience-dependent flexibility

- Cash Support for Low-Income Families Impacts Infant Brain Development – Duke University’s Baby’s First Years study on environmental enrichment and brain development

Latest in Gift Science

-

Why Toddlers Say “Mine” (It’s Not Selfishness)

by

· Updated

Continue reading →: Why Toddlers Say “Mine” (It’s Not Selfishness)That fierce MINE! over someone else’s birthday present isn’t bad behavior. It’s your toddler’s brain making a developmental leap, and understanding the science helps you respond without shame or struggle.

-

Should Boys Play With Dolls? The Science Says Yes

by

· Updated

Continue reading →: Should Boys Play With Dolls? The Science Says YesWhen my son asked for a baby doll and my mother-in-law redirected him to trucks, I watched his face fall. New brain imaging research reveals why that moment matters more than most parents realize.

-

Gifts Kids Will Remember: The Science Behind Them

by

· Updated

Continue reading →: Gifts Kids Will Remember: The Science Behind ThemYour child tore through six birthday presents and forgot them all, but still talks about that one afternoon making bracelets together. New research reveals the three brain mechanisms that determine which gifts become lasting memories and how to activate them.

-

DIY Gifts Kids Can Make: The Science of Why

by

· Updated

Continue reading →: DIY Gifts Kids Can Make: The Science of WhyYour grandmother treasures that wonky clay handprint more than the cashmere scarf you carefully selected. New research reveals three psychological mechanisms that explain why homemade gifts hit differently and how to help your kids tap into that power.

-

Sibling Gift Jealousy: Why It Happens and What Helps

by

· Updated

Continue reading →: Sibling Gift Jealousy: Why It Happens and What HelpsYour five-year-old has been the perfect helper for exactly twelve minutes before disappearing under the table in tears. Understanding why children measure love in wrapped packages can transform how you handle every gift-giving moment.

-

When Do Toddlers Learn to Share? Age by Age Guide

by

· Updated

Continue reading →: When Do Toddlers Learn to Share? Age by Age GuideYour toddler just grabbed a toy and won’t let go while another parent watches. Here’s why that fierce mine is actually a sign of healthy brain development and what actually works instead of forced sharing.

Share Your Thoughts