My 8-year-old builds elaborate Minecraft worlds with her older brother while my 4-year-old stacks wooden blocks beside them. Both are completely absorbed. Both are problem-solving, creating, imagining. So why does one make me feel like a “good” parent and the other trigger a low hum of guilt?

I couldn’t let that question go. My librarian brain sent me down a rabbit hole of developmental psychology studies, meta-analyses, and expert interviews. What I found surprised me—and challenged almost everything the internet was telling me about this debate.

Key Takeaways

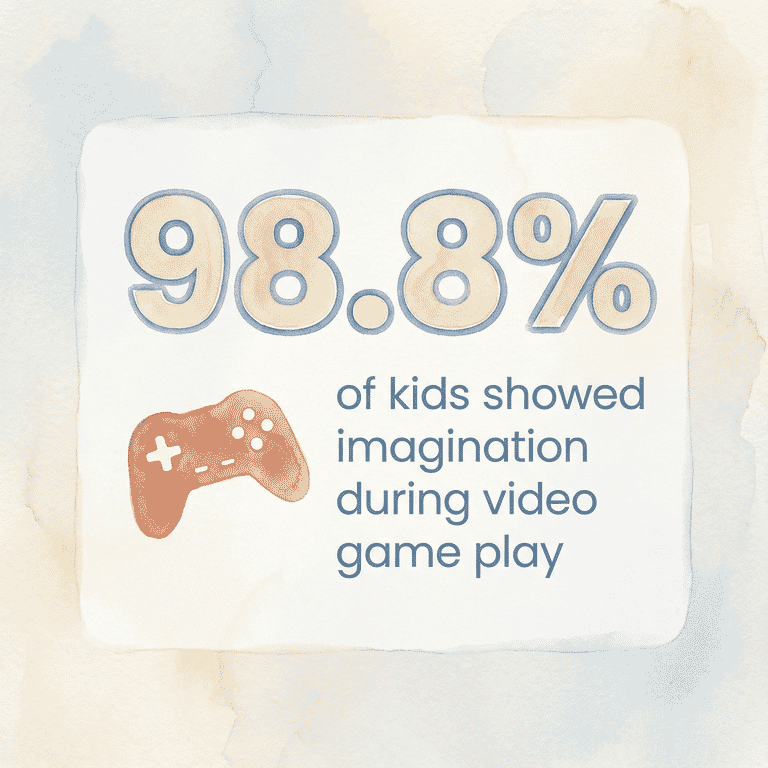

- Research shows 98.8% of children demonstrate imagination during video game play—the digital vs. traditional debate misses the point

- Three variables matter more than screen status: child agency, parent engagement, and open-ended design

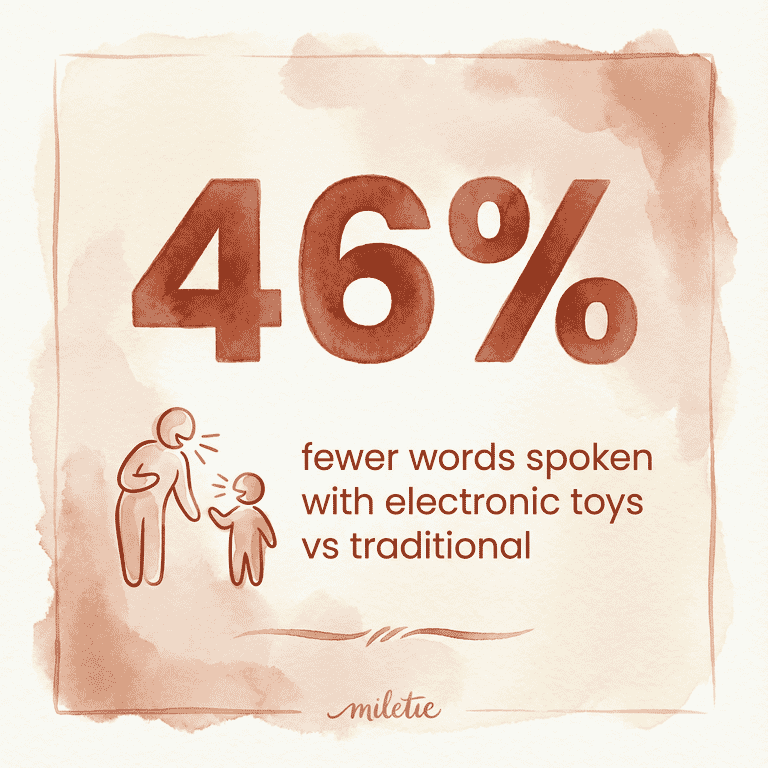

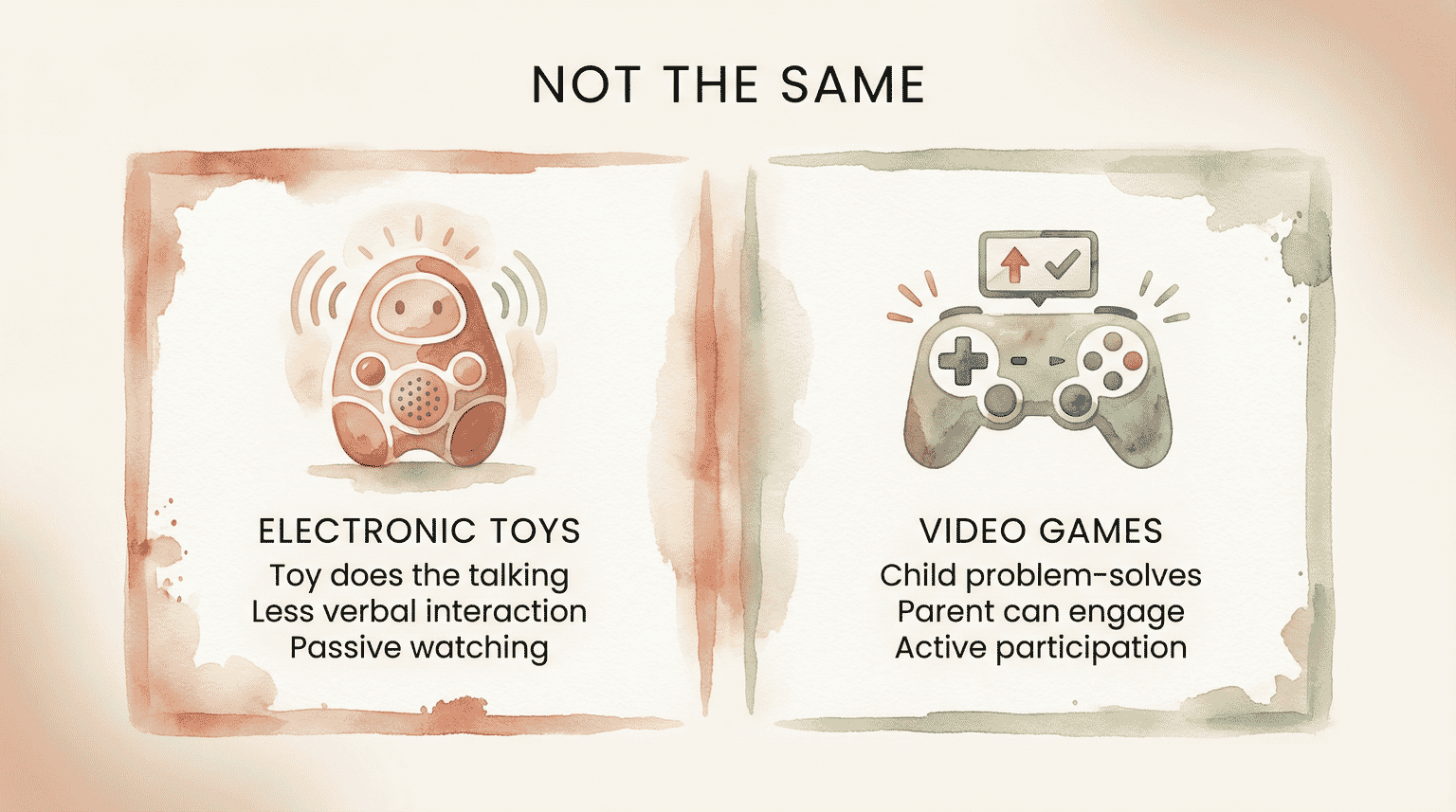

- Electronic toys and video games are not the same category—passive electronic toys reduce verbal interaction by 46%

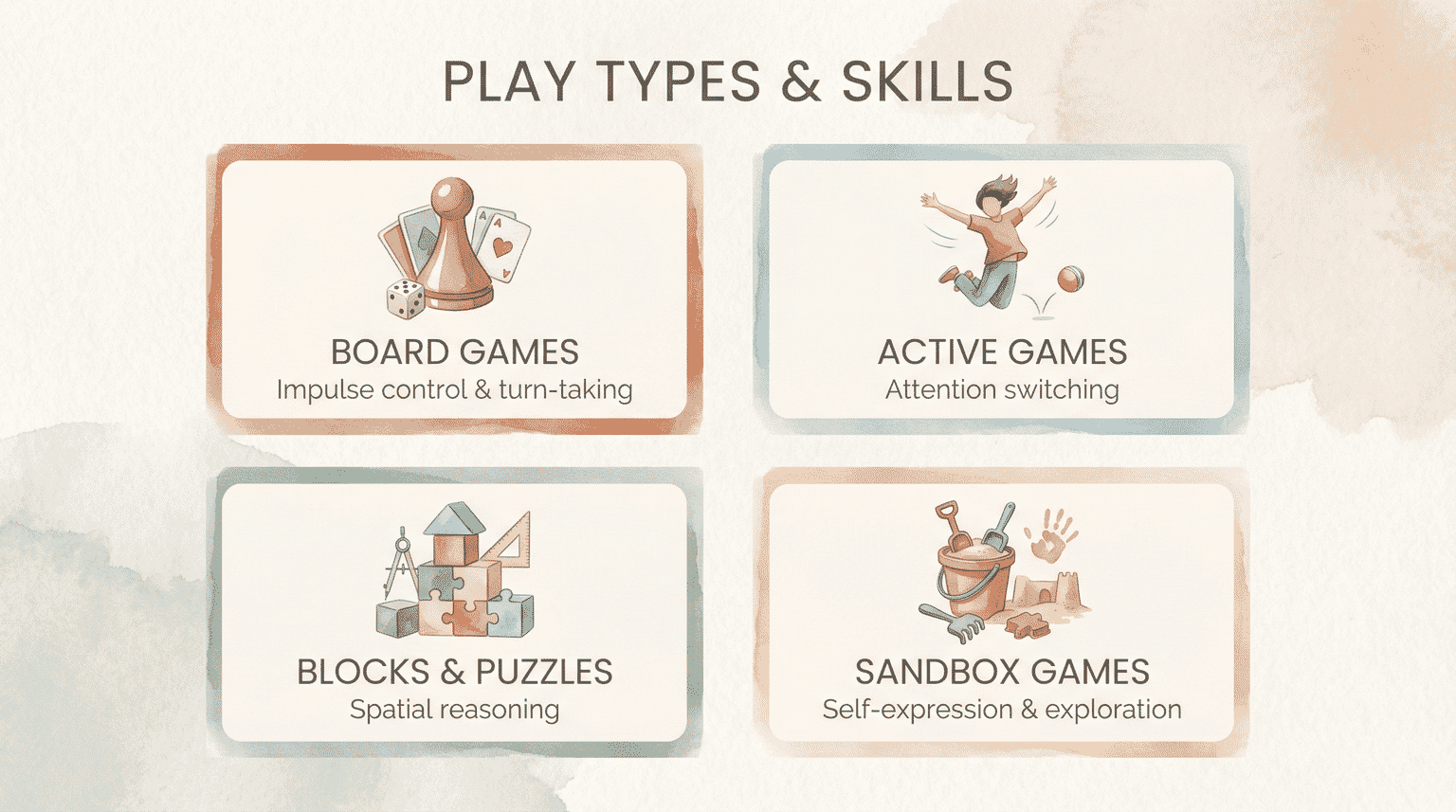

- Different play types build different skills: board games for impulse control, blocks for spatial reasoning, sandbox games for self-expression

- The best gift is often the one you’ll actually play together—parent presence transforms any play experience

The Debate That Misses the Point

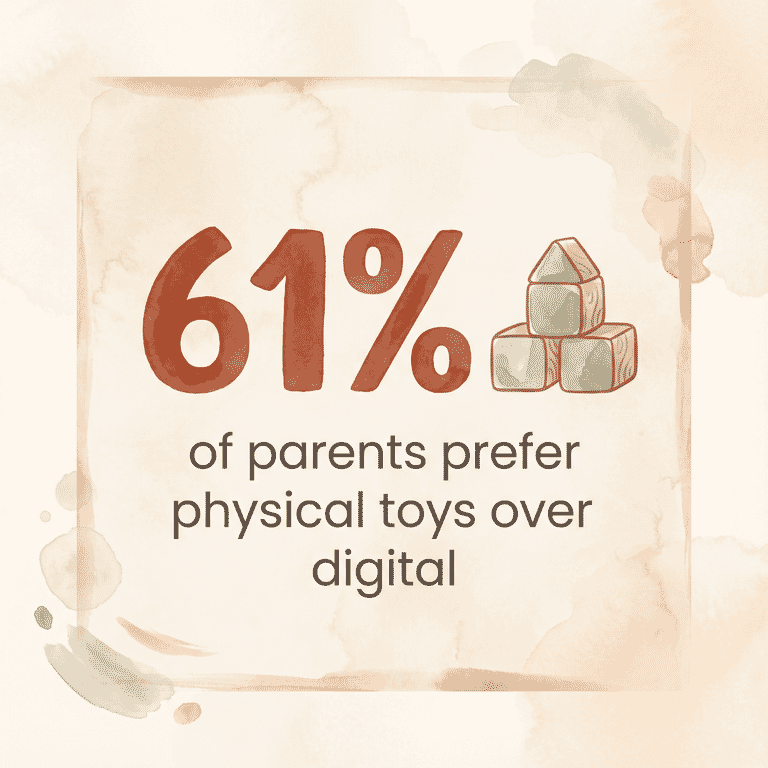

Here’s the tension most parents feel: 61% of American parents still prefer physical toys over digital alternatives, according to Berkeley Business Review research. Only 14% prefer digital. We overwhelmingly want traditional play to win.

That preference runs deep. It connects to our own childhoods, to images of wholesome play, to a vague sense that “real” toys are somehow better for developing minds.

But our instincts and the research don’t always align the way we expect them to.

Dr. Claire McCarthy at Harvard Health has noticed something troubling about modern parenting patterns.

“Parents and children are literally forgetting how to play. Parents used to bring toys to entertain their children while they waited to see me; now they just hand their child their phone.”

— Dr. Claire McCarthy, Harvard Health

The conventional wisdom sets this up as a binary—screens bad, blocks good. Pick a side. But when I dug into what researchers actually found, the picture was far more nuanced. The category of the toy—digital versus traditional—matters far less than three variables almost nobody talks about.

What the Research Actually Shows

Here’s the finding that stopped me: a 2021 NIH study observed seven-year-olds playing with both traditional toys and video games. The researchers tracked “internal state references”—moments when children voiced what characters think and feel, demonstrating imagination and social understanding.

98.8% of children made internal state references during video game play. That’s not a typo. Nearly every child engaged imaginatively while gaming.

This challenges the assumption that screens suppress imagination. Children aren’t passive recipients—they’re actively narrating, problem-solving, and emotionally engaging with digital worlds.

But here’s the nuance—children made more total internal state references with traditional toys. And the type differed: during video games, kids narrated their own experiences (“I’m scared!”), while during toy play, they voiced characters’ perspectives (“Mum is happy”).

Both demonstrate imagination, but differently. What researchers call these internal state references are windows into developing theory of mind—the ability to understand that others have thoughts and feelings different from our own. And children are practicing this skill in both contexts.

“In today’s world a lot of adults and kids are building those imaginary worlds, but it’s in the computer. It’s Minecraft and Fortnite, and it is creative. You’re building things, you’re making up your own stuff, but it’s also on a screen.”

— Dr. Barry Kudrowitz, Toy Designer and Researcher, University of Minnesota

This doesn’t mean everything digital is fine. It means we’re asking the wrong question.

The Three Variables That Actually Predict Developmental Value

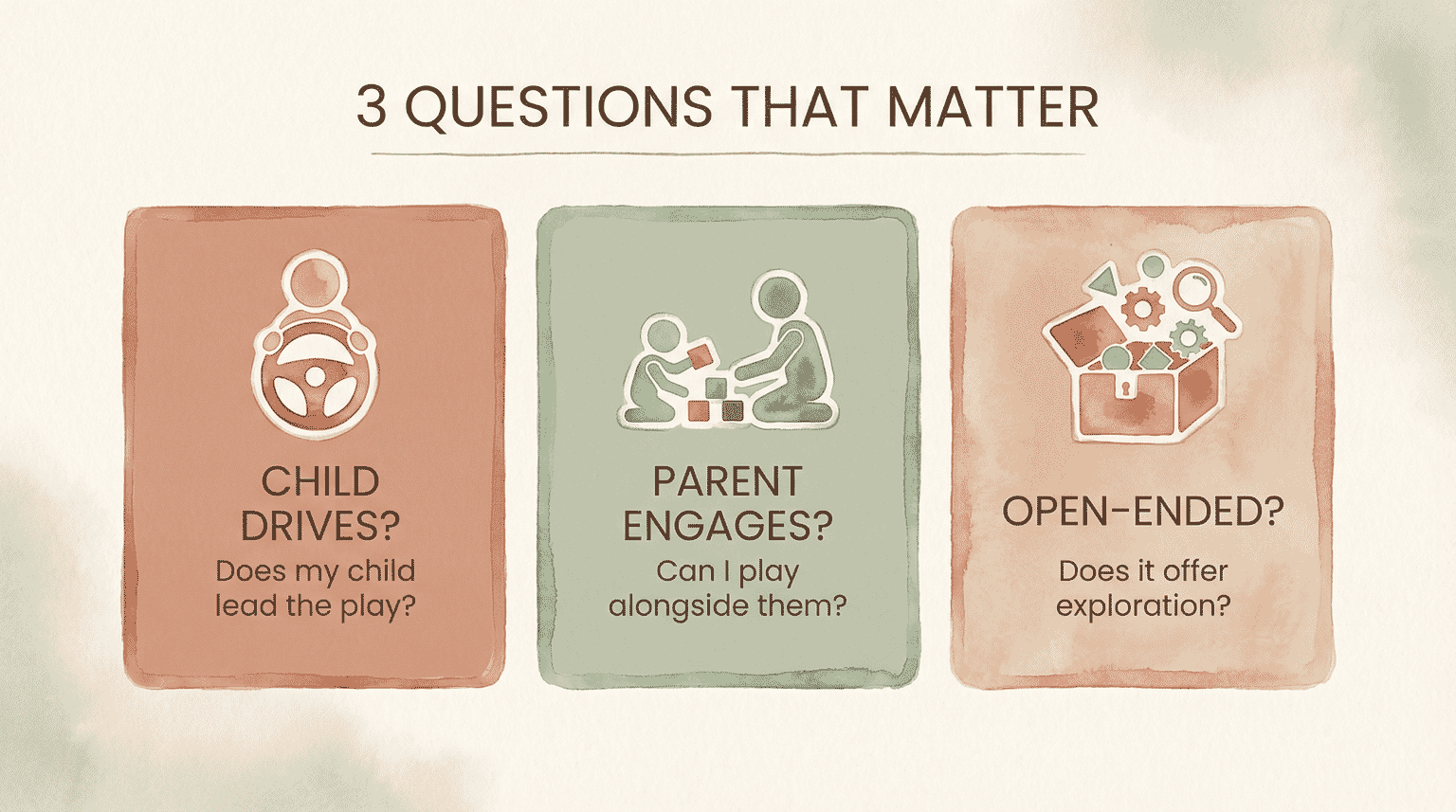

After reviewing the research, I’ve identified three factors that matter far more than whether a gift has a screen. These apply equally to a $200 gaming console and a $20 toy from the store.

Variable 1: Does Your Child Drive the Play, or Does the Toy?

Dr. Doris Bergen, Distinguished Professor Emerita of Educational Psychology at Miami University, has spent decades studying how children play.

“A really good toy is one that doesn’t do everything itself, but has the child do it. Unfortunately, I think some toys designed do too much and there isn’t really even room for children to do very much with them.”

— Dr. Doris Bergen, Distinguished Professor Emerita, Miami University

This is the child agency question. Does your child’s imagination, curiosity, and problem-solving lead the experience? Or do they passively watch the toy perform?

Dr. Kudrowitz offers a practical test: “What makes a toy a good toy is that it could be used in a variety of different contexts and it doesn’t die. You can use it for generations, for example, or in multiple different ways of playing.”

By this measure, a sandbox video game where kids build their own worlds offers more agency than an electronic toy that sings the same song when you press a button. Traditional toys aren’t automatically better—passive traditional toys exist, and active digital experiences exist too.

Variable 2: Can You Meaningfully Engage Alongside Them?

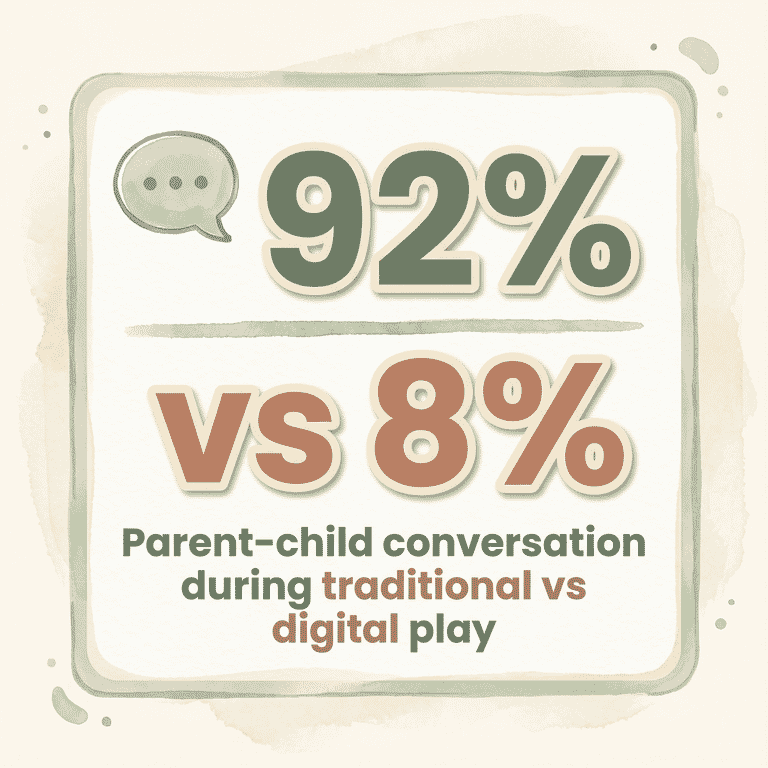

Here’s a statistic that shaped how I think about this: A 2023 study from Slovenia found that during traditional toy play, 92% of parents reported intense verbal communication with their children. During digital play? Just 8%.

That gap is staggering. But it’s not necessarily the toy’s fault.

Something has shifted in how parents approach gaming with their kids. Research from the University of Oregon found that 74% of parents now play video games with their children—up from just 30% in 2008.

When parents actively engage during gaming, the experience transforms. In my house, this looks like my husband sitting with our 10-year-old while she plays, asking questions, reacting to the story, problem-solving together. That’s completely different from handing her a device and walking away.

The parent’s presence changes everything—for digital gift experiences just as much as traditional ones.

Variable 3: Does It Offer Open-Ended Possibilities or One Narrow Track?

Not all games are created equal, and the research is specific about what matters.

A 2024 meta-analysis of 136 early childhood studies found game-based learning produced moderate-to-large cognitive benefits overall. But puzzle games showed particularly strong effects on cognitive development—an effect size of 0.63, which researchers consider large.

Meanwhile, research on cooperative versus competitive games found that cooperative game settings increase sharing attitudes and prosocial behaviors. Time spent in prosocial gaming settings correlated positively with helping behaviors months later.

The design of the game—whether it promotes problem-solving, collaboration, and open-ended exploration—matters more than the simple fact that it’s digital.

The Electronic Toy Investigation

Here’s where I need to make a critical distinction that most articles miss: electronic toys are not the same as video games.

The flashing, beeping toys marketed to young children—the ones that light up and sing when pressed—are a separate category with their own research profile. And it’s not encouraging.

A 2022 Frontiers in Psychology study found children produced 7.74 utterances per minute during traditional toy play versus just 5.29 during electronic toy play—a 46% difference in verbal output.

The electronic toys’ sounds, music, and flashing lights “dominated the interaction, interrupting children’s utterances and decreasing the space available for parent-child communication.”

Parents tend to let the toys do the talking for them. And when children talk less, parents have fewer opportunities to respond and build language skills.

This is fundamentally different from a child actively problem-solving in a video game while a parent engages beside them. We need to stop treating “screen time” as one monolithic category when the research clearly shows distinctions.

What Specific Play Types Actually Develop

I’ve watched this play out eight times now: different types of play build different skills. Here’s what the research confirms:

Board games positively predict inhibition skills—the ability to control impulses and wait for turns. A 2021 study on executive functions found board games’ social nature requires children to adapt behavior and inhibit reactions.

Exergames (active video games like those using motion controls) positively predicted switching skills—the ability to shift attention between different tasks. They combine physical and cognitive challenges requiring constant alternation between focused and divided attention.

Blocks and puzzles build spatial reasoning. Research from SUNY shows infants who play with blocks develop better spatial perception, and toddlers with more puzzle play have stronger spatial skills as preschoolers.

Sandbox digital games promote self-expression and constructivist learning—where children construct their own understanding through exploration rather than receiving prescribed knowledge.

Pretend play (traditional or digital) develops theory of mind—understanding that others have different thoughts and feelings. When my 6-year-old voices her doll’s emotions or my 12-year-old role-plays in a story-driven game, they’re practicing the same fundamental skill.

The key insight: match the play type to what your child needs to develop, regardless of category. For more on finding that balance between screen time gifts and other options, the approach stays consistent—quality and context over category.

The Parent’s Evaluation Framework

Next time you’re standing in the toy aisle or scrolling through options online, ask three questions:

Does my child drive this, or does it drive my child? Look for open-ended possibilities, not predetermined scripts.

Can I meaningfully engage alongside them? The best gift is often the one you’ll actually play together.

Does it offer exploration or just consumption? Building, creating, and problem-solving beat passive watching every time.

These questions work for video games, wooden toys, art supplies, and everything in between. They shift the focus from “is this category acceptable?” to “will this support my child’s development?”

Understanding how digital gift-giving is reshaping childhood helps put individual choices in context. But the research is clear: what matters is not whether a toy plugs in. What matters is whether it powers up your child’s imagination—or powers it down.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are video games bad for child development?

Quality matters more than category. A 2024 meta-analysis found video games produced moderate-to-large cognitive benefits, with puzzle games showing even stronger effects. Outcomes depend on game design, session length, and whether adults engage alongside children.

What toys are best for brain development?

Toys where “the child does it, not the toy.” Open-ended options like blocks, construction sets, and pretend play figures consistently outperform toys that do everything themselves. For cognitive flexibility, active video games showed benefits; for inhibition and turn-taking, board games performed best.

Do educational video games actually work?

Evidence suggests they can. A 2024 meta-analysis found game-based learning produced moderate-to-large effects on cognitive development. However, parent or educator guidance during play maximizes learning gains—the game doesn’t teach alone.

What’s better for kids—toys or tablets?

Neither category is inherently superior. Research shows children engage imaginatively with both. However, traditional toys generate more parent-child verbal interaction and stronger outcomes for motor and sensory development. The best approach combines both: traditional toys for language-rich interaction, quality games for cognitive challenges.

Over to You

How do you balance gaming and traditional toys at your house? I’d love to hear whether you’ve found ways to feel good about both—or whether the screen guilt persists even when you know the research.

Your gaming-guilt stories help other parents realize they’re not alone in this.

References

- APA Speaking of Psychology Podcast – Expert interviews on what makes toys developmentally valuable

- NIH Study on Internal States in Play – Research on imaginative engagement in video games vs. traditional toys

- Frontiers in Psychology – Electronic toys and language development

- PMC Meta-Analysis on Game-Based Learning – Comprehensive review of cognitive effects

- Slovenia Parent Survey – Parent-child interaction differences by toy type

- Berkeley Business Review – Parent preferences and toy industry trends

- Executive Functions Study – Board games, exergames, and cognitive development

- University of Oregon Research – Parent co-play trends and educational value of games

Share Your Thoughts