Your daughter comes home from Maya’s birthday party, and instead of bouncing with excitement about the games they played, she’s quiet. Finally, it comes out: “Maya got an iPad. And AirPods. And her own TV for her room.”

You know that look. It’s not just disappointment—it’s something closer to confusion. Like the rules of her world just shifted and she’s trying to figure out where she stands now.

Here’s what’s actually happening in her brain—and what to say in each of the scenarios where gift comparisons create these moments.

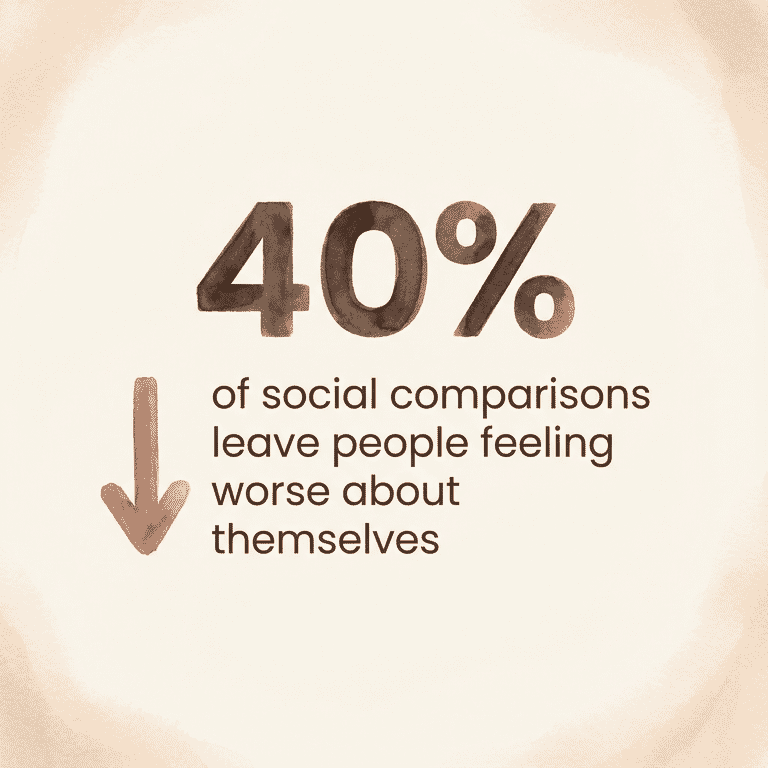

A 2023 study tracking daily social comparison found that nearly 40% of comparisons left people feeling worse about themselves, while only 4% felt better. And when those comparisons happen on social media? University of Missouri researchers found they feel “more personal and powerful” than anything that happens face-to-face.

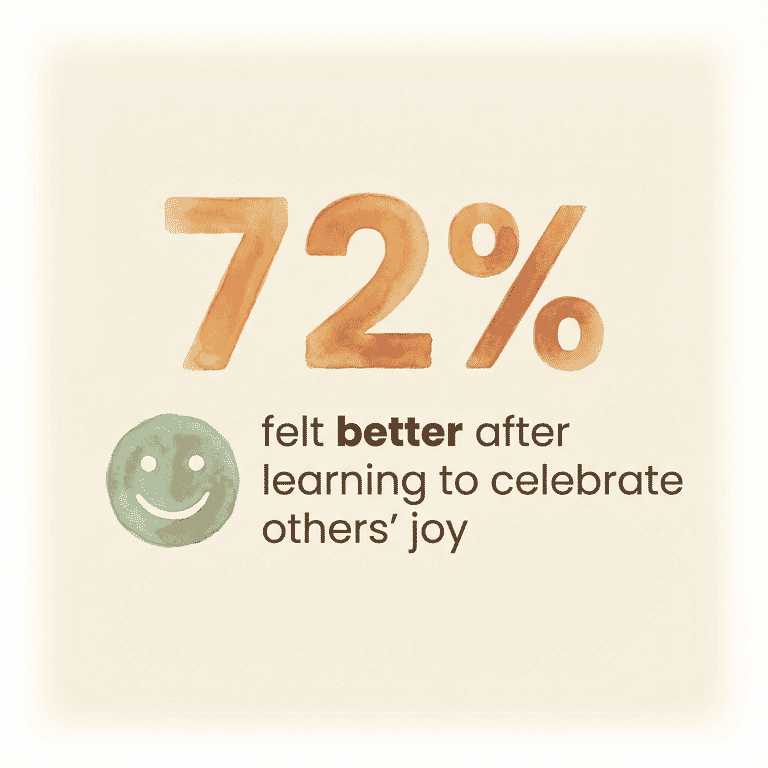

That number might sound discouraging, but there’s good news buried in that same research. A technique called “social savoring”—learning to feel genuine happiness for others’ good fortune—helped 72% of participants feel better.

Even more encouraging? 92% would recommend it to others. It’s a skill we can teach, and I’ll show you exactly how in each scenario below.

Key Takeaways

- Nearly 40% of social comparisons leave kids feeling worse—but social savoring can flip the script

- Validate feelings first, then redirect with curiosity—not lectures about gratitude

- Digital comparisons hit harder because curated content feels personally achievable

- Naming the comparison possibility before events reduces its power significantly

- You are the protective factor—through modeling, not lecturing

The Birthday Party Aftermath

The situation: Your child comes home from a friend’s party talking about the amazing gifts the birthday kid received—the sheer quantity, the expense, the “coolness factor.”

What’s happening: Your child just experienced in-person comparison in a concentrated form. They watched a peer receive gift after gift while an audience oohed and ahhed. The social dynamics amplified everything—this isn’t just about wanting stuff, it’s about witnessing someone else being celebrated.

I’ve sent kids to probably 200 birthday parties over the years. The ones who come home unsettled aren’t necessarily the ones who saw the “best” gifts—they’re the ones who didn’t have words for what they were feeling.

What to say:

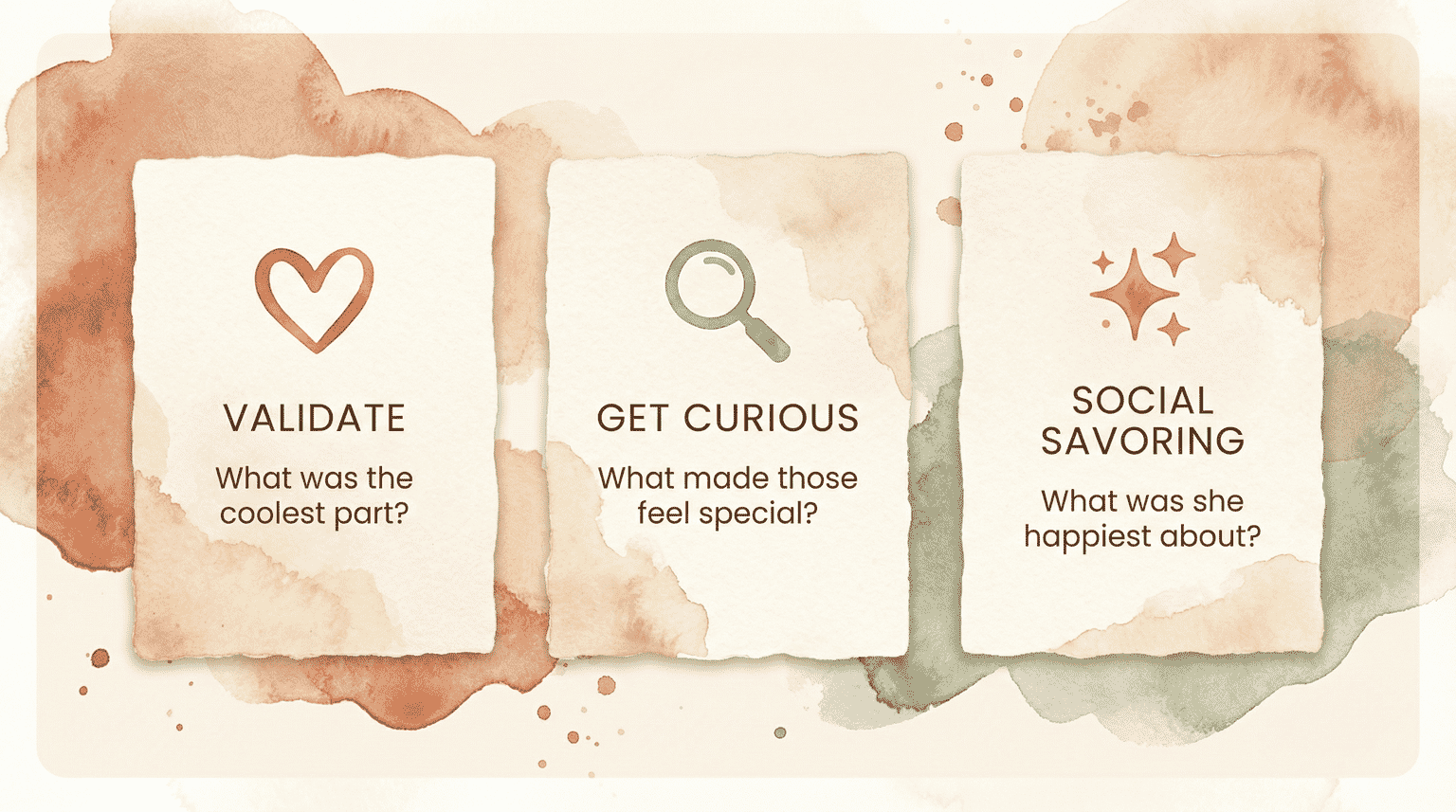

“It sounds like Maya got some really exciting things. What was the coolest part of watching her open presents?”

— First, validate

Once you’ve acknowledged their experience, get curious about what’s driving the feeling.

“What do you think made those gifts feel so special?”

— Then get curious

Finally, introduce the concept of social savoring—shifting focus from what someone got to what they experienced.

“What do you think Maya was happiest about today—not just the stuff, but the whole thing?”

— Introduce social savoring

The goal isn’t to talk them out of their feelings. It’s to expand their focus from “she got more than me” to “she had a great day”—which is actually easier for kids to feel good about.

When you’re navigating the escalating birthday party expectations that seem to define modern childhood, remember: your child is trying to make sense of social dynamics, not just coveting an iPad.

The Christmas Morning Crisis

The situation: Christmas morning starts magically. Then your child picks up their phone and starts scrolling through friends’ gift posts. Within minutes, their mood has shifted completely.

What’s happening: This is FOMO in its purest form. A 2025 BMC Psychology study found that social media exposure significantly increases “upward comparison”—measuring ourselves against people who seem to have it better.

The researchers describe FOMO as “the uneasy feeling of missing out on what one’s peers are doing, or knowing that they own more or better things.” Your child was genuinely happy five minutes ago. Then they saw a carefully curated highlight reel that made their very real, very wonderful Christmas morning feel insufficient.

Here’s the hopeful part: teaching kids to celebrate others’ joy actually works. The research shows that 72% of participants felt better after learning this skill.

It’s not about forcing positivity or denying real feelings. It’s about building a mental muscle that gets stronger with practice—and eventually becomes automatic.

What to say:

“I noticed your mood just changed. What are you seeing on there?”

— In the moment

Naming what’s happening helps them recognize the pattern.

“Social media shows everyone’s best moment. Right now, you’re comparing your whole morning to their one perfect picture.”

— Name it

Then offer a gentle redirect—not a demand.

“What if you put the phone in another room until after breakfast? Those posts will still be there, but this morning won’t.”

— Redirect gently

The pause-before-scrolling technique really works. I’ve watched my tweens struggle with this—they’re not trying to be ungrateful, they just haven’t developed the mental calluses that help adults scroll past curated content without feeling worse.

Prevention matters here: The research shows that even ten minutes of mindfulness or intentional presence before scrolling can significantly reduce negative comparison effects. On Christmas morning, that might look like a “no phones until after breakfast” rule that applies to everyone—adults included.

The Social Media Scroll

The situation: Your child regularly encounters TikTok unboxings, Instagram gift hauls, and Snapchat stories from peers showing off new stuff.

What’s happening: This isn’t a single comparison moment—it’s a chronic drip of curated content that makes “better” seem normal and achievable. Research from Frontiers in Psychology (2025) found that extreme upward comparisons—where there’s a large gap between you and what you’re seeing—are directly associated with lower self-esteem.

Makenzie Schroeder, a University of Missouri researcher, explains why this hits so hard:

“Filters that make someone look slimmer create what many perceive to be a more perfect version of themselves that’s easy to reach with just a few clicks. That makes the comparison feel very personal and even more powerful…”

— Makenzie Schroeder, University of Missouri Researcher

The same applies to gift content. When your child’s actual friend (not a distant influencer) posts about their haul, it feels personally relevant and achievable—which somehow makes it hurt more.

What to say:

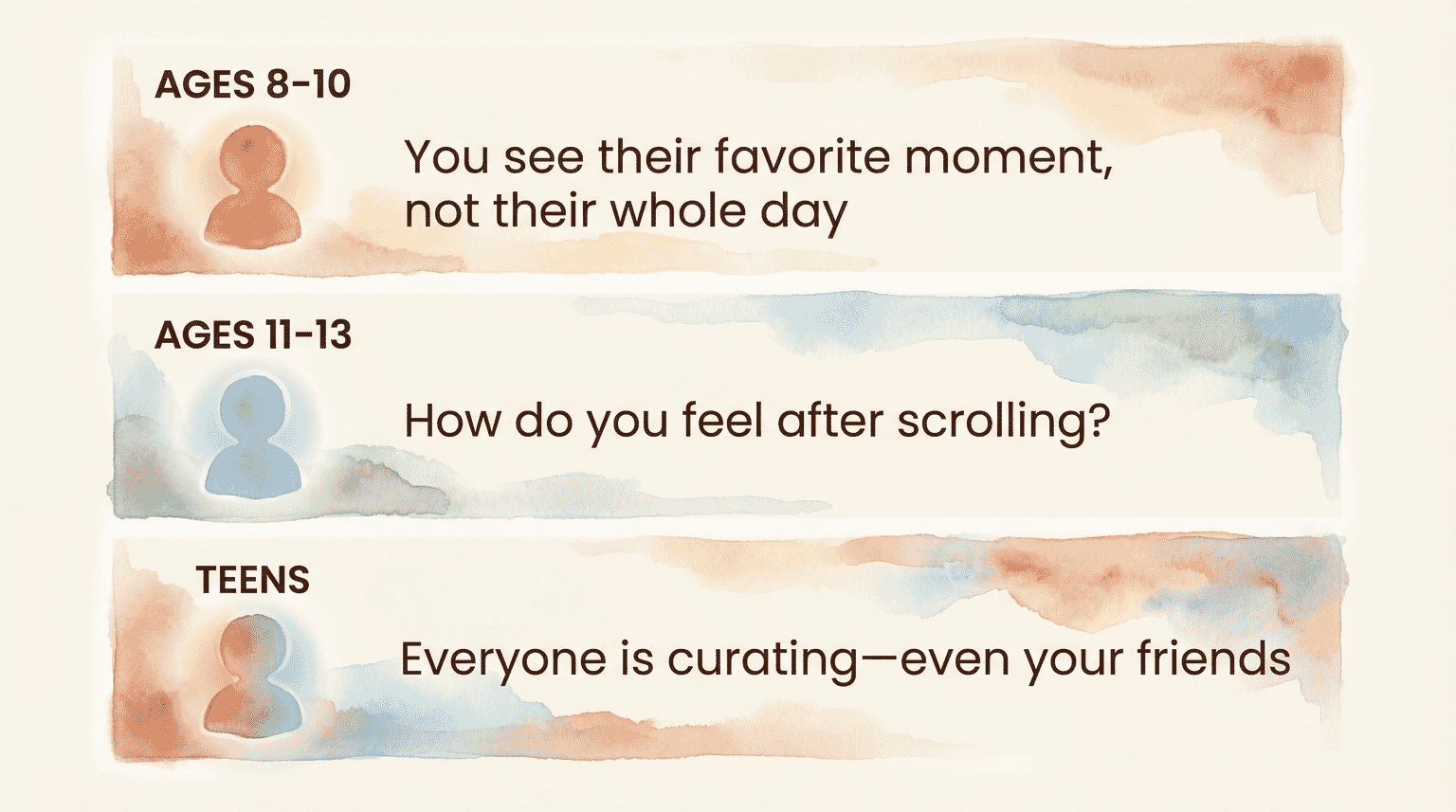

“When you see what people post, remember you’re seeing their favorite moment, not their whole day. Nobody posts the boring parts.”

— For ages 8-10

“How do you feel after scrolling through those posts? Sometimes noticing the feeling helps you decide how much you want to see.”

— For ages 11-13

“Your friends are curating too. Everyone is. What would someone think your life looks like if they only saw your posts?”

— For teens

If you want to go deeper on helping kids understand Instagram isn’t real life, that conversation works best as an ongoing dialogue rather than a one-time lecture.

A 2024 study published in Discover Psychology found that Instagram or Snapchat use prior to age 11 was linked to more problematic digital behaviors. The researchers suggest limiting social media access for younger children minimizes some of the negative effects of early exposure.

The Classroom Conversation

The situation: Your child reports that “everyone at school was talking about how cool Maya’s presents were.”

What’s happening: This is social status signaling, and it’s as old as schoolyards. But your child isn’t just comparing gifts—they’re comparing their social standing based on gift-worthiness. That’s a heavier load.

What to say:

“That sounds like it was a big topic. How did you feel being part of that conversation?”

— Don’t dismiss the social reality

Let them explore what’s really driving the feeling.

“What made those gifts the thing everyone talked about?”

— Explore without lecturing

Then apply social savoring in a way that shifts from comparison to connection.

“It sounds like Maya felt really special that day. What makes you feel that way—not just from gifts, but from anything?”

— Apply social savoring

The social savoring approach—learning to feel genuine happiness for someone else—works here because it shifts your child from “I didn’t have that” to “she had a great moment.” Over time, that’s actually easier to carry.

Princeton research found that people who made frequent social comparisons were more likely to experience envy, guilt, and defensiveness—and this was independent of their self-esteem levels. Building self-esteem alone won’t fix comparison problems. Reducing comparison frequency helps.

The Family Gathering

The situation: Cousins open gifts at Grandma’s house, and the disparity is visible. Different families, different budgets, different philosophies about gift-giving—all on display.

What’s happening: This is comparison with extra complexity. You can’t criticize Aunt Sarah’s choices without family fallout. Your child might be seeing differences they don’t fully understand, and you might be managing your own feelings about how your family’s gifts stack up.

What to say:

“Different families do gifts differently—there’s no right or wrong way. In our family, we [focus on X/choose gifts that Y/etc.].”

— To your child

If they push for more explanation, stay curious rather than defensive.

“I can see you noticed that. How are you feeling about it?”

— If they push

“What do you think Cousin Jake was most excited about? Not just the big things—the whole day?”

— Introduce perspective

I’ll be honest: this one is hard for me too. When my kids were younger, I sometimes felt defensive about our gift choices compared to relatives who went bigger.

What helped was reminding myself—and eventually them—that our family’s approach is intentional, not limited. Research consistently shows that parental influence decreases adolescents’ materialistic tendencies while peer influence increases them. You are the protective factor here.

The Prevention Playbook

The scenarios above are about responding in the moment. But the research points to something more powerful: preventing comparison distress before gift-giving occasions.

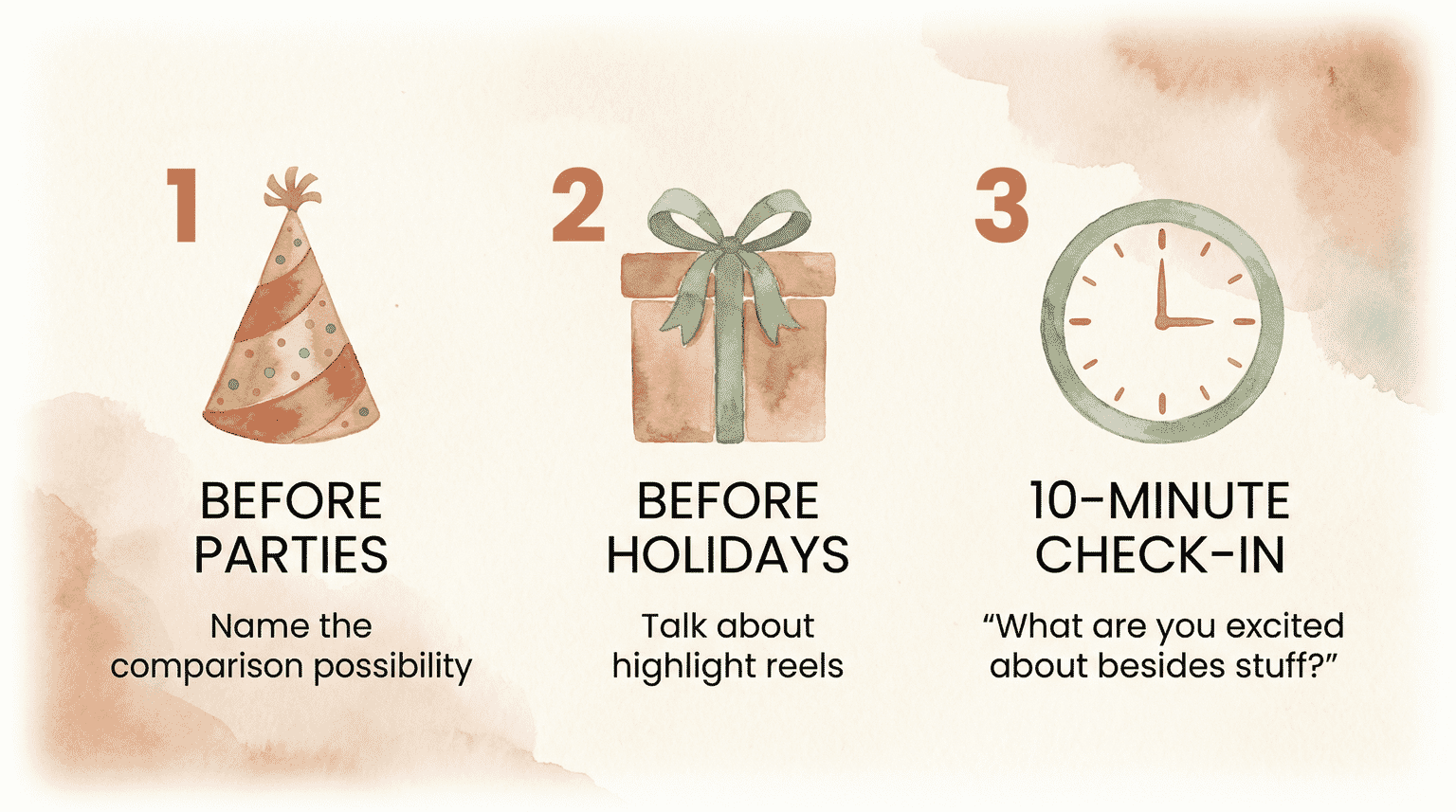

Before birthday parties:

“You’re going to see [Friend] open a lot of presents. Some might be really fancy. That can feel weird sometimes—like wondering why your birthday was different. If that happens, it’s okay to feel it. We can talk about it after.”

— Name the comparison possibility

Simply naming the possibility reduces its power.

Before holidays:

“Social media is going to be full of people posting their best gifts. Remember that you’re seeing everyone’s highlight reel on the same day—that’s a lot of comparison in a small space.”

— Talk about highlight reels

The 10-minute intervention: Research found that even a brief mindfulness practice significantly reduced negative comparison effects. Before parties or holiday gatherings, try a simple check-in:

“Let’s take a few minutes. What are three things you’re looking forward to today that have nothing to do with stuff?”

— 10-minute check-in

Year-round gratitude that doesn’t feel preachy: Forget forced gratitude journals. What works better is noticing out loud: “That game you got for your birthday last year—you’ve played it probably 50 times. That’s a gift that really fit you.”

Building the “Enough” Muscle

Gift comparison isn’t a problem to eliminate—it’s a developmental opportunity. Every time your child feels that pang of “they got better stuff,” they’re actually building the emotional muscles they’ll need for adulthood, where comparisons only intensify.

Social savoring—the practice of genuinely feeling happy for others’ good fortune—isn’t just a nice idea. Research shows it works, kids can learn it, and most who practice it continue on their own.

Elizabeth Behm-Morawitz, professor at the University of Missouri, offers a simple guiding principle:

“Being real is sometimes the healthiest option.”

— Elizabeth Behm-Morawitz, Professor, University of Missouri

In our family, that’s looked like admitting when I felt comparison pangs too (yes, even at my age), talking openly about why we make the gift choices we do, and practicing—imperfectly—the art of celebrating others’ joy without diminishing our own.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does my child always compare gifts?

Gift comparison is normal developmental behavior driven by children’s need to understand where they fit among peers. Social media amplifies what used to be limited to occasional in-person observations—now children see curated gift content constantly, triggering more frequent upward comparisons.

How do I teach my child not to be jealous of friends’ toys?

Research supports teaching “social savoring”—the practice of feeling genuine happiness for others’ good fortune. Start by validating feelings, then redirect with curiosity: “What do you think made her happiest about it?” A 2023 study found 72% of participants continued practicing this skill after learning it.

Does social media make gift comparison worse for kids?

Yes. University of Missouri researchers found digital comparisons feel “more personal and powerful” than in-person ones because curated content makes idealized versions seem achievable. Nearly 40% of social comparisons leave people feeling worse, and that percentage climbs with social media exposure.

What should I say when my child says a friend got better presents?

Avoid dismissive responses like “You should be grateful.” Instead: validate first (“It sounds like seeing those gifts made you feel like yours weren’t as special”), get curious (“What made those seem better?”), then introduce perspective without lecturing (“What do you think your friend was most excited about?”).

How can I prevent gift jealousy before it happens?

A brief conversation before gift-giving occasions helps: name the comparison possibility, acknowledge it’s normal, and give your child language for the feeling. Research shows even 10 minutes of mindfulness or intentional presence before social media exposure significantly reduces negative comparison effects.

What About You?

How do you handle the “but Maya got a better gift” conversations? I’d love to hear what scripts have worked—and whether the comparison talk has gotten easier or harder as your kids have gotten older.

These conversations are so much easier when we figure them out together.

References

- Intervening on Social Comparisons on Social Media – JMIR Formative Research study on social comparison frequency and the social savoring intervention

- The associations between social comparison on SNS and self-esteem – Frontiers in Psychology research on extreme upward comparisons and self-esteem

- Social comparison on Instagram – Discover Psychology study on early social media use and mindfulness interventions

- Social media exposure, social comparison, and FOMO – BMC Psychology research on FOMO mechanisms and comparison cycles

- Looking in the digital mirror: Mizzou researchers – University of Missouri research on why digital comparisons feel more powerful

Share Your Thoughts