More toys means more enrichment. More learning. More happiness. Right?

That’s what I believed when my oldest was a toddler. I filled bins with colorful options, ignoring the 20-toy rule, convinced I was setting her up for success.

Then one Christmas morning, my then-five-year-old ripped through twelve presents in four minutes, looked around at the carnage of wrapping paper, and asked, “Is that all?”

Something was clearly wrong. If you recognize this pattern, you’re not alone. My librarian brain couldn’t let it go. I started digging into the research—and what I found surprised me.

Key Takeaways

- Children with only 4 toys played twice as long and more creatively than those with 16 toys in controlled studies

- Excess toys create decision fatigue in developing brains, leading to shorter attention spans, less creativity, and more conflict

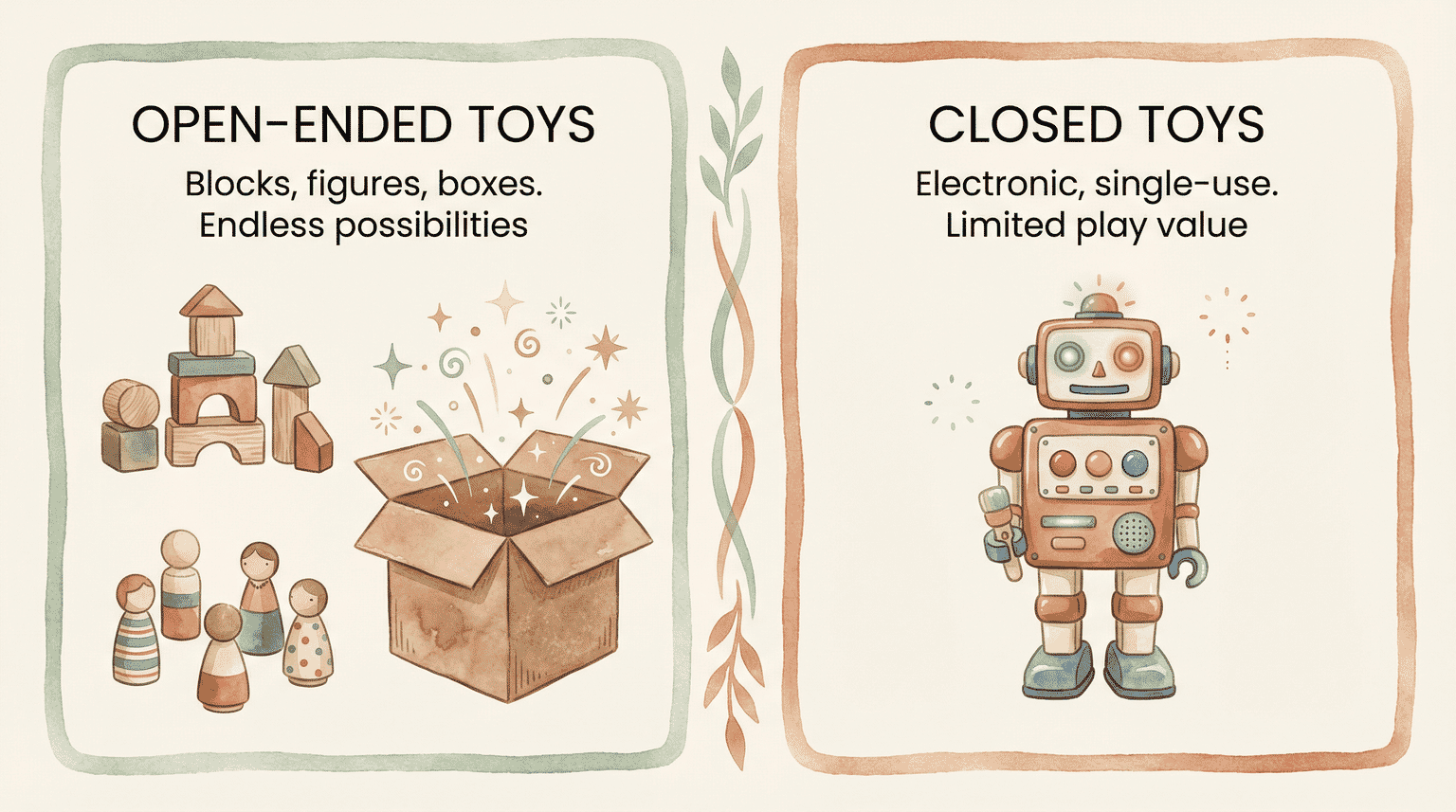

- Open-ended toys like blocks and figures outperform electronic single-use toys for deep, imaginative play

- Research recommends limiting to around 20 toys with 6-10 accessible at a time with the rest stored for monthly rotation—try the 4-bin system

The Conventional Wisdom (And Why It’s Wrong)

The instinct to provide abundance runs deep. We want our children to have opportunities, choices, stimulation. When relatives ask what to bring, we add to the list. When birthdays approach, we fill carts. The toy aisle promises learning, development, and joy in every brightly-colored package.

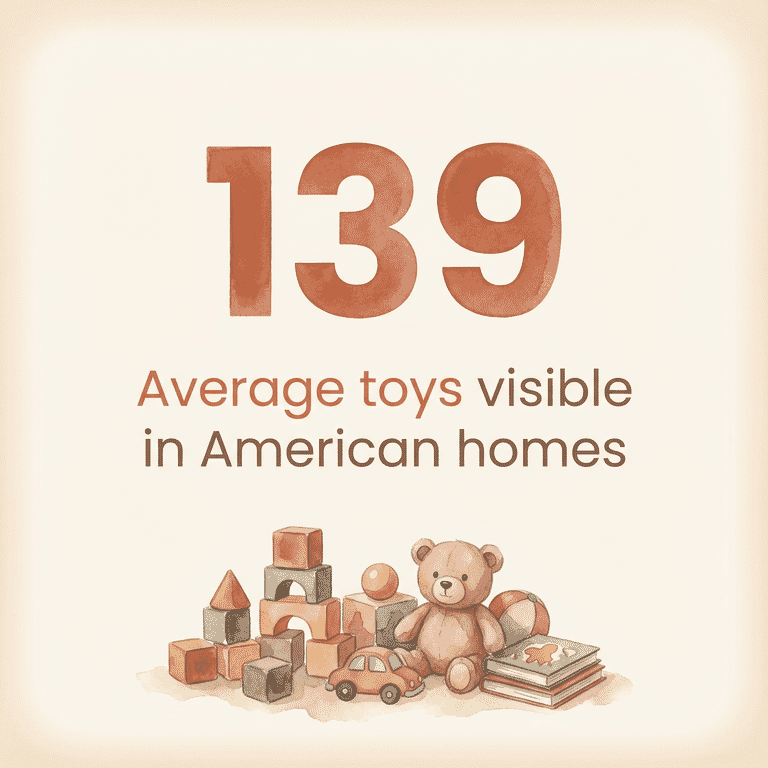

We’re not imagining this pressure. A 2023 Psychology Today analysis found that middle-class American families had an average of 139 toys visible and easily accessible to their children—typically spread across living rooms, dining areas, and bedrooms.

When researchers surveyed parents for a 2024 study, the average home contained nearly 90 toys. Some parents couldn’t even provide a count—they just wrote “a lot.”

Here’s the disconnect every parent recognizes: surrounded by all those toys, our kids don’t actually play with them. They dump bins looking for something “better.” They abandon new toys within minutes. They complain they’re bored while standing in a room full of options.

Sound familiar? There’s a reason for this—and it’s not that your child is ungrateful.

What the Research Actually Shows

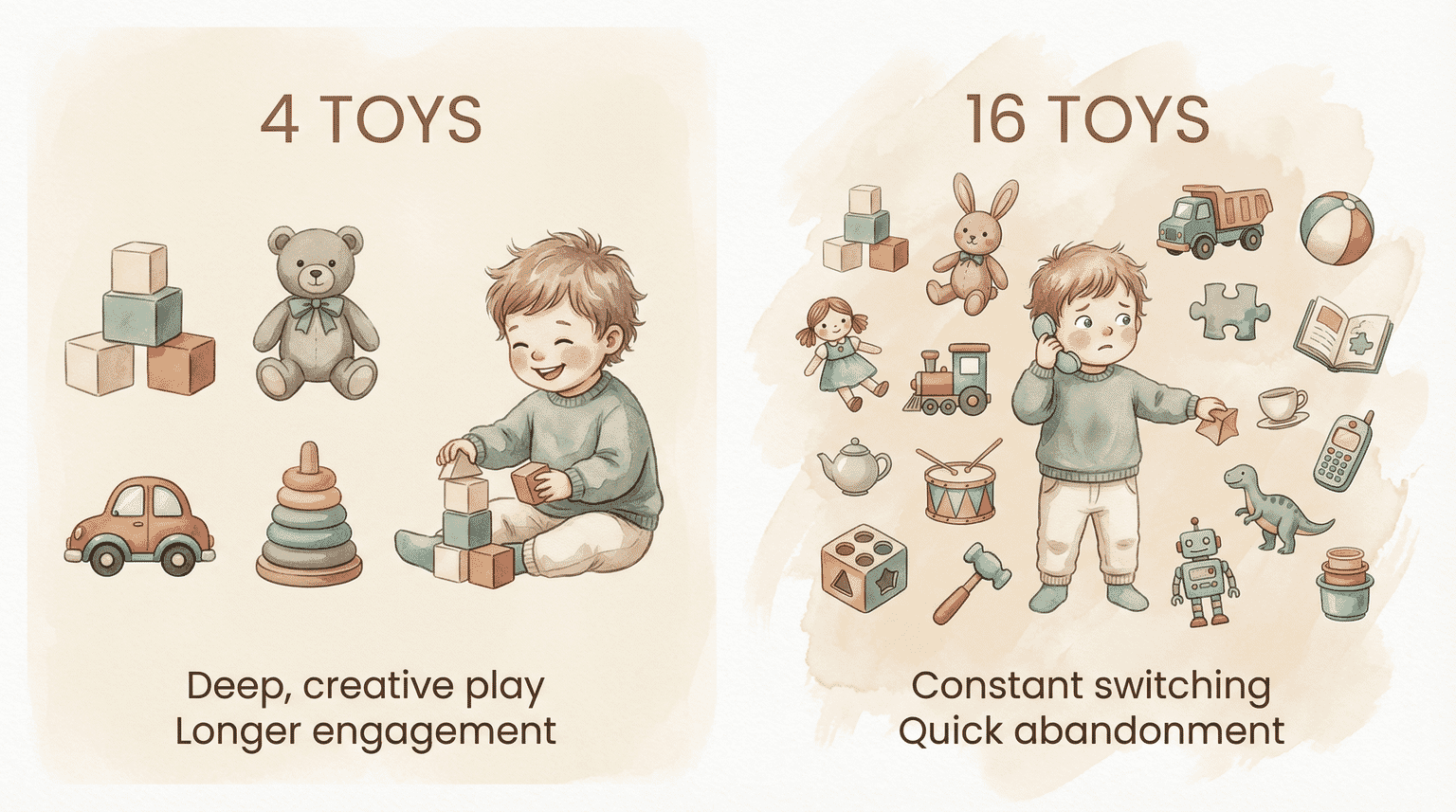

Dr. Carly Dauch and her colleagues at the University of Toledo designed an experiment I wish I’d known about years ago. They brought 36 toddlers (ages 18-30 months) into a controlled play environment and randomly assigned them to one of two conditions: a room with four toys, or a room with sixteen toys.

The results weren’t subtle.

Children with only four toys played twice as long with each toy compared to children in the sixteen-toy condition. But duration wasn’t the only difference—they played in more varied, imaginative ways. They explored toys from multiple angles. They invented new uses. They engaged deeply.

The sixteen-toy children? They constantly abandoned play to explore the next option. Pick up, put down, move on. Pick up, put down, move on. They played with more toys overall but learned less from each one.

This pattern held regardless of toy type—educational, pretend, action, or vehicles. The quantity itself was the variable that mattered.

Research shows children with fewer toys play better because limited options encourage deeper engagement. In a controlled study, toddlers with only 4 toys played twice as long as those with 16 toys and demonstrated more creative, varied play behaviors.

With fewer choices, children aren’t overwhelmed by options and instead explore each toy’s full potential through imaginative play.

Northwestern University’s Early Intervention Research Group puts it directly: “Research has shown that access to fewer toys at a time is related to better quality of play.” When children have limited options, they’re almost forced to get creative with what’s available.

The Brain Science Behind “Less Is More”

Here’s what’s actually happening in your child’s brain—and why it matters.

Attention is a limited resource, especially in developing minds. Every toy in view competes for that attention. For toddlers and young children whose executive function is still under construction, filtering out irrelevant options requires cognitive effort they can barely spare.

When a child faces sixteen toys, their brain must repeatedly make decisions: Play with this one? Or that one? What about the one behind it? Each decision depletes mental resources. Psychologists call this decision fatigue, and it affects adults too—but children’s developing brains are particularly vulnerable.

“An excess of toys can prevent children from focusing on any one thing long enough to learn from it, causing them to feel overwhelmed and potentially even shutting down emotionally.”

— Claire Lerner, Child Development Researcher

I’ve watched this overwhelm in my own house. My four-year-old standing frozen in front of his toy shelf, whining that he has “nothing to play with.” He’s not spoiled—he’s cognitively flooded. His brain can’t complete the selection process, so he gives up.

The paradox is real: more options lead to less engagement, less creativity, and less learning. The deep, sustained play where actual development happens requires the kind of focused attention that abundance makes nearly impossible.

The Five Hidden Costs of Toy Overload

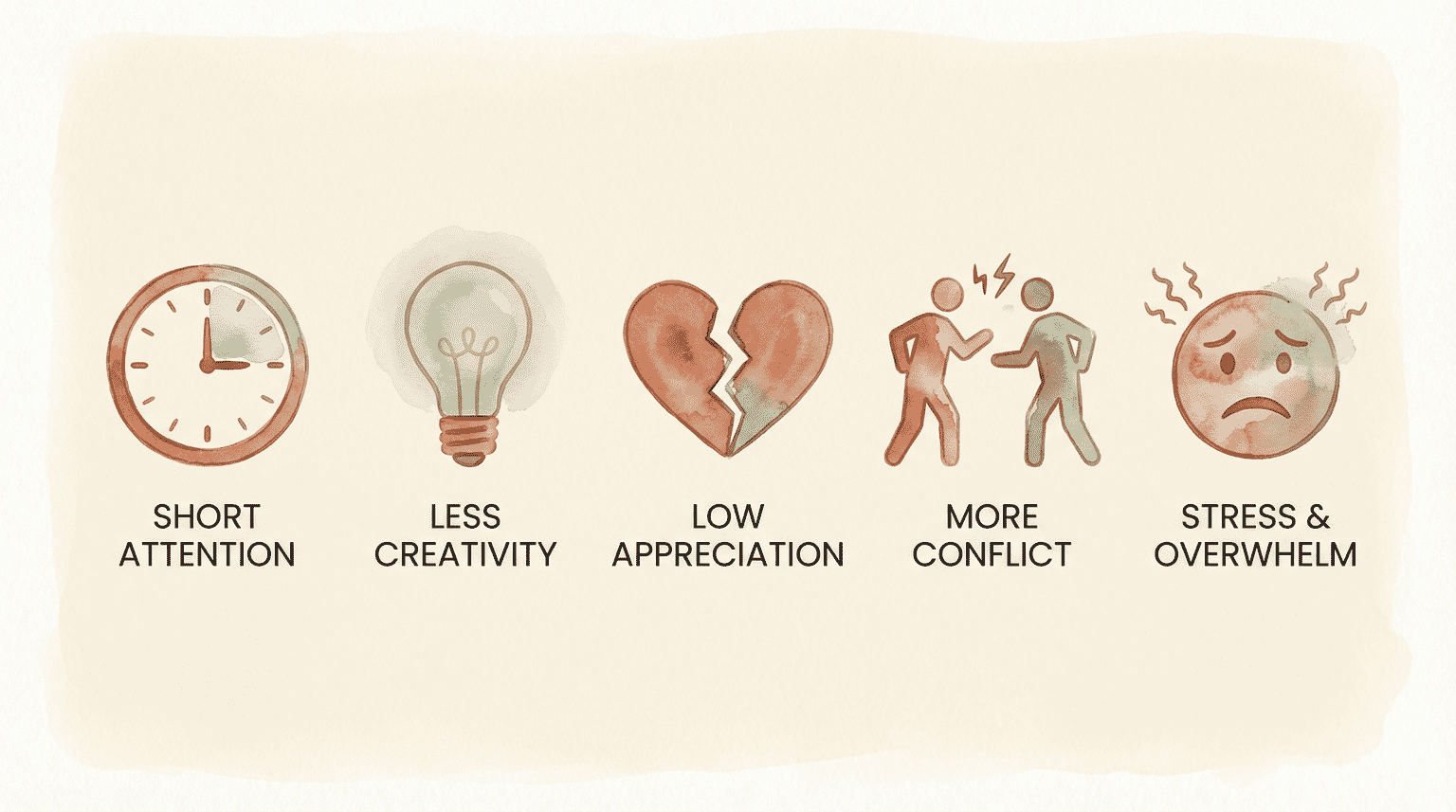

Beyond play quality, research has documented five specific ways excess toys can harm development:

1. Shortened Attention Spans

When children constantly flit from one toy to the next, their brains adapt to that pattern. They learn to seek the next novel thing rather than pushing through the less-exciting middle parts of play where creativity and problem-solving actually develop.

2. Reduced Creativity

Toys that do everything leave nothing for the child’s imagination. When the doll talks, the truck makes sounds, and the game announces winners, children become passive consumers of entertainment rather than active creators of play.

3. Less Appreciation

This one stung when I recognized it in my own kids. Abundance breeds entitlement; scarcity creates value. When toys are easily replaced, children don’t learn to care for what they have.

4. Increased Conflict

Here’s a counterintuitive finding: more toys actually increase possessiveness and fighting. With fewer toys, children must negotiate and share—essential social skills. With abundance, they hoard.

5. Overwhelm and Stress

Decision fatigue doesn’t just reduce play quality—it manifests as meltdowns, shutdown, and that frustrating whining we mistake for ingratitude. Children aren’t trying to be difficult; their brains are genuinely overloaded.

One study found children now play an average of 8 hours less per week than children two decades ago. While screens deserve some blame, the irony shouldn’t escape us.

We’ve given children more toys than any generation in history, and they’re playing less.

What Actually Matters: Quality Over Quantity

If fewer toys work better, which toys should make the cut?

Researchers at Eastern Connecticut State University spent a decade studying this question, examining over 100 toys in preschool classrooms. Their findings transformed how I evaluate toys for my own kids.

The critical distinction is open-ended versus closed toys.

“A simple wooden cash register in our study inspired children to engage in lots of conversations related to buying and selling—but a plastic cash register that produced sounds when buttons were pushed mostly inspired children to just push the buttons repeatedly.”

— TIMPANI Research Team, Eastern Connecticut State University

Open-ended toys can become anything. Closed toys can only be one thing.

The same researchers observed children using plain hardwood blocks to create “houses, zoo enclosures, castles, and roads—and children pretended that individual blocks were cell phones, cars, or sandwiches.” A single set of blocks served as construction material, communication device, transportation, and food. That’s the power of open-ended play.

“If there’s only one way to use a toy, it’s kind of hard for children to use it for a long time period. If there’s 10 buttons to push and you’ve pushed all 10 buttons, then that’s really the end of what you can do with the toy.”

— Dr. Doris Bergen, Professor Emerita of Educational Psychology

Two toy categories consistently outperformed all others:

- Construction toys (blocks, Magna-Tiles, basic LEGO) — open-ended, with enough pieces for flexible building

- Replica play toys (small figures, animals, vehicles) — inspiring elaborate pretend scenarios

Dr. Barry Kudrowitz, who studies creativity and toy design, offers my favorite example: “The cardboard box is a great example… It’s a fort, it’s a rocket ship, they’re drawing all over the walls, they’re cutting out holes. And that was free, and it’s compostable.”

When evaluating which toys deserve space in your home, ask two questions:

- Can this toy be used in multiple ways?

- Does my child do the work, or does the toy?

Putting It Into Practice

The research points toward a specific recommendation: 6-10 toys accessible at a time, with the rest stored for rotation.

Northwestern’s Early Intervention Research Group suggests a simple system: pack away half of your child’s toys and switch them monthly. Stored toys feel novel and exciting when they return—you get the “new toy” engagement without buying anything.

Here’s how I’ve implemented this with my younger kids:

Maintain balance across categories:

- 1-2 construction options (blocks, magnetic tiles)

- 1-2 replica/pretend play items (figures, dollhouse, play kitchen tools)

- 1-2 creative materials (crayons, playdough)

- 1-2 sensory or active play items

Start gradually. I learned the hard way that a dramatic toy purge triggers massive resistance. (Try the 5-day birthday reset instead.). Instead, slowly rotate items out. Kids rarely notice what’s gone—they notice what’s present.

Address the influx. The real challenge isn’t reducing toys; it’s preventing accumulation. Birthdays, holidays, and well-meaning relatives create constant inflow. This is where a gift-giving philosophy that prevents toy overload becomes essential. For specific strategies, our guide on managing holiday gift quantities helps navigate those conversations.

For a detailed implementation guide, including what to do with removed toys and how to handle resistance, see our complete toy rotation system.

The Real Gift

Here’s what I’ve learned watching eight children across seventeen years: fewer toys isn’t deprivation—it’s freedom.

My kids with access to fewer toys play longer. They complain less about boredom. They create more elaborate pretend worlds. They’re less grabby at stores and more appreciative when gifts arrive.

The counterintuitive truth is that reducing toys IS the enrichment we were seeking with abundance. Deep engagement builds attention span. Open-ended play develops creativity. Constraint teaches appreciation.

When my four-year-old spends forty-five minutes building a “dragon hospital” with blocks and random figurines, having elaborate conversations between patients and doctors, I’m watching exactly what the research predicts. His brain is doing the work—not the toys.

That’s the gift worth giving.

Frequently Asked Questions

How many toys should a child have?

Research suggests 6-10 toys accessible at a time, with the rest stored for rotation. A University of Toledo study found toddlers played twice as long and more creatively with just 4 toys compared to 16. Northwestern University recommends packing away half of a child’s toys and rotating them monthly to maintain novelty while preventing overwhelm.

Do too many toys overstimulate children?

Yes. Child development research shows excess toys create decision fatigue and overwhelm in developing brains. When surrounded by too many options, children struggle to focus on any single toy long enough to engage deeply. This overstimulation can manifest as shortened attention spans, increased stress, and paradoxically, less play overall.

What happens when a child has too many toys?

Children with too many toys experience five documented effects: shortened attention spans from constant novelty-seeking, reduced creativity when toys do the thinking for them, less appreciation for what they have, increased conflict over possessions (paradoxically), and emotional overwhelm that can cause shutdown.

Why won’t my child play with their toys?

Counterintuitively, children often won’t play with their toys because they have too many options. Research shows that excess toys create decision paralysis—children abandon play quickly to explore the next option rather than engaging deeply with any single toy. Reducing accessible toys to 6-10 at a time typically results in longer, more creative play sessions.

I’m Curious

Have you noticed a difference when your kids have fewer toys out? I’d love to hear whether less has actually led to deeper play—or whether it’s just led to more requests for new stuff.

Your real-world experiments help me understand what actually works beyond the studies.

References

- Psychology Today – Are Fewer Toys Better for Your Toddler? – University of Toledo research on toy quantity and play quality

- Eastern Connecticut State University – TIMPANI Toy Study – 10-year study on what makes toys effective

- Psychology Today – How Many Toys Should Your Toddler Have? – Research on toy quantity in American homes

- Northwestern University Early Intervention Research Group – Evidence-based toy rotation recommendations

- Anamalz – Can Too Many Toys Harm Development? – Developmental impacts of toy excess

- Nurtured Nest – A Simplistic Approach to Toys – Practical guidance on toy minimalism

Share Your Thoughts