It’s Christmas morning. My 4-year-old is counting presents under the tree—not looking at tags, just counting. “Maya has MORE!” she announces, pointing at her 15-year-old sister’s pile. Never mind that Maya’s “pile” includes a laptop for high school that cost more than everything else combined. To my 4-year-old, three boxes beat one box. Every time.

This scene plays out annually in my house. I’ve seen variations across all eight of my kids. And here’s what my librarian brain couldn’t let go: why does “unfair” feel so devastating to children at certain ages, and why do kids at different stages interpret fairness so differently?

Turns out, there’s fascinating developmental science behind every “That’s not fair!” you’ve ever heard. Understanding it won’t eliminate sibling gift drama entirely—I’ve got eight kids, so I’m realistic—but it transformed how I approach gift-giving in my family.

Key Takeaways

- Equal means same; fair means appropriate. Children develop the ability to understand this distinction gradually—and at predictable stages.

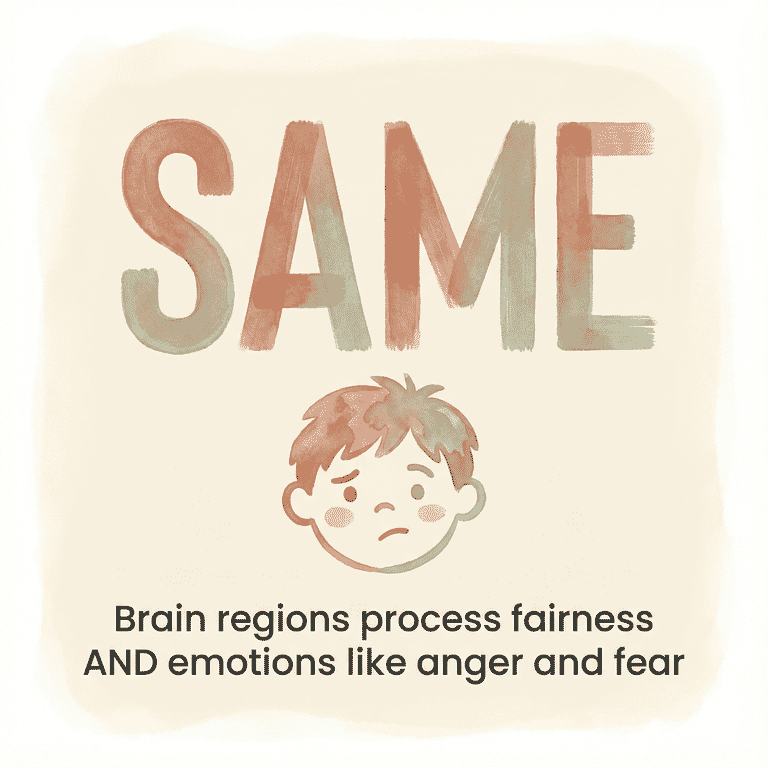

- The brain regions processing fairness are the same ones processing anger and fear, which is why unfair situations feel intensely personal to kids.

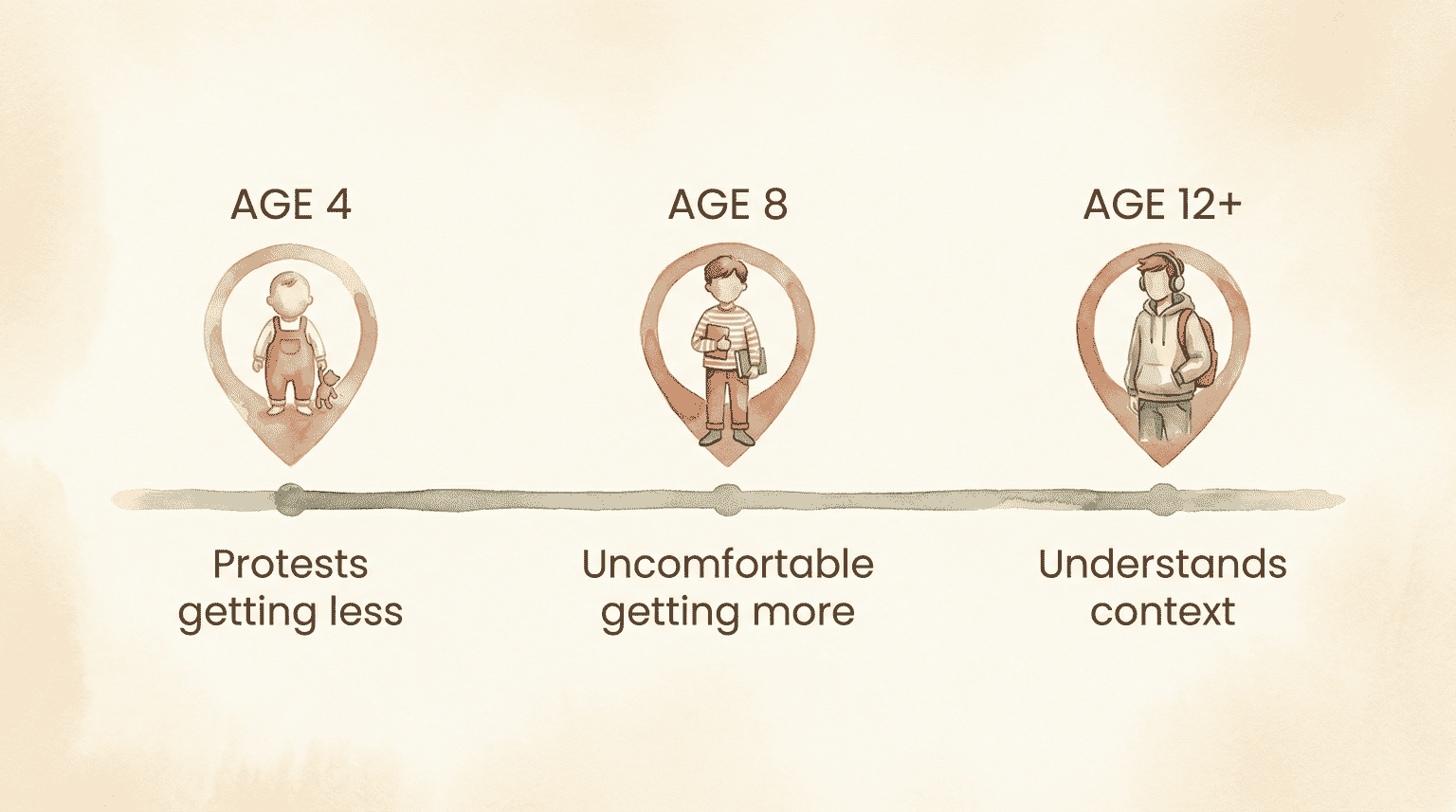

- By age 4, children across all cultures will incur costs to reject distributions that disadvantage them.

- Around age 8, children develop discomfort about receiving MORE than siblings—not just less.

- Your response to “that’s not fair!” should match their developmental stage for best results.

The Core Distinction: Equal vs. Fair

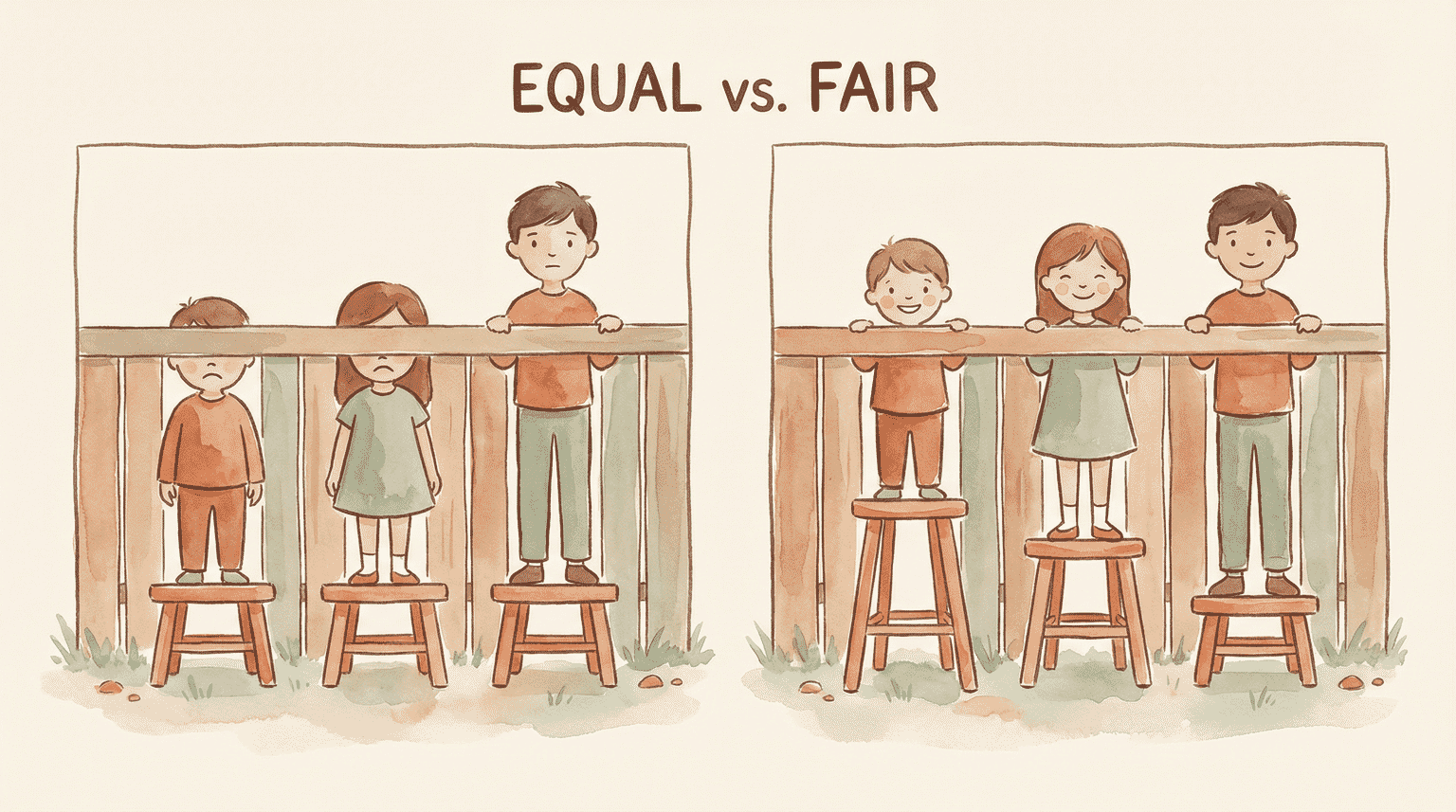

Here’s the simplest way to understand the difference: equal means everyone gets the same thing; fair means everyone gets what they need.

Think of three kids trying to see over a fence. Giving each kid an identical stool would be equal. Giving each kid a stool sized to their height so everyone can actually see? That’s fair.

Research cited by Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child puts it this way: “Fair doesn’t mean everyone gets the same. Fair means everyone gets what they need to learn and grow.”

The challenge for parents is that children develop the ability to understand this distinction gradually—and at predictable stages. A strategy that works beautifully for your 8-year-old will completely backfire with your 4-year-old, because their brains are processing fairness in fundamentally different ways.

Why Unfairness Feels So Big to Children

Before diving into age-specific strategies, understanding why unfairness triggers such intense reactions helps build empathy for what your child is experiencing.

Research published in Frontiers for Young Minds reveals something striking: the same brain regions that create feelings of anger, sadness, and fear also create our sense of fairness. This means your child’s meltdown over an “unfair” gift isn’t drama—it’s their brain’s emotional alarm system firing.

Additionally, the brain regions responsible for self-control don’t fully mature until early adulthood. A 2022 PMC study found that “young children’s violation of the principle of distributive justice is not due to a lack of understanding of right and wrong but rather to the inability to implement behavior control when tempted by resources.”

Translation? Your child might genuinely understand that their sibling’s gift is appropriate—and still melt down. They’re not being manipulative; they literally cannot yet override that emotional alarm.

Ages 2-4: The Counting Years

At this stage, children are concrete thinkers. They count packages, not dollar values. Three small gifts beat one large gift. Every single time.

Research shows that by 4 months old, infants already look longer at unequal distributions—suggesting fairness awareness is hardwired from the start. By age 3, many children show clear signs of caring about fairness, particularly around sharing and taking turns.

What works at this stage:

Make gifts appear similar. Equal-sized boxes, similar amounts of wrapping paper, comparable unwrapping time. The 2-year-old doesn’t care that her sister’s boots cost four times as much as her stuffed animal—she cares that they both got a big box.

“You each get presents that are just right for you! Let’s see what’s in YOUR special box.”

— Try saying this to ages 2-4

In my house, I’ve learned to wrap my toddler’s gifts in more packages if needed. The $15 art supplies become three separately wrapped items instead of one. Is it more work? Yes. Does it prevent meltdowns? Absolutely.

Ages 4-6: The Inequality Alarm Awakens

Around age 4, something significant shifts. A 2024 meta-analysis confirmed what I’ve observed with my own kids: “In every culture studied to date, children as young as 4 years old incur costs to reject distributions that disadvantage them.”

This is when you’ll start hearing “But she got MORE!” with genuine distress. Your child has developed what researchers call “disadvantageous inequity aversion”—they’re upset when they perceive getting less than others.

By age 5, children can now judge unequal outcomes as “clearly unfair.” A 2022 Frontiers in Psychology study found this is a distinct developmental milestone: five-year-olds rate unequal distributions as unfair, while younger children often don’t make this explicit judgment.

What works at this stage:

Begin introducing the “different needs” concept—but keep it simple and concrete.

“Your sister needs ballet shoes for her class. You needed the soccer ball. Both are important for what you’re learning.”

— Try saying this to ages 4-6

The key is connecting different gifts to different activities or needs they already understand. Abstract explanations about “value” won’t land yet.

Ages 6-8: The Transition Zone

This is where it gets interesting. Children in this range are developing the ability to consider context and procedure—why gifts differ, not just that they differ.

Research shows that children at this stage can begin processing simple explanations of circumstance, though they’re still primarily focused on outcomes. They’re ready to hear reasoning before gift opening, which can significantly reduce protest.

I’ve found my 6- and 8-year-olds respond well to advance framing. When I explain beforehand why this birthday or holiday involves different gifts for different kids, the actual unwrapping goes much more smoothly.

What works at this stage:

Explain your reasoning before the gift-giving event. Be specific and concrete.

“This year, Maya is getting something bigger because she’s starting middle school. Next year when you start, you’ll get something similar.”

— Try saying this to ages 6-8

For managing Christmas comparison moments, I’ve learned to have these conversations the week before—not in the heat of unwrapping chaos.

Ages 8-11: Abstract Fairness Emerges

Around age 8, another major shift occurs. Children develop “advantageous inequity aversion”—meaning they may feel uncomfortable when they receive more than their sibling, not just when they receive less.

The Frontiers in Psychology researchers found that what changes with age is “not children’s recognition that the child who receives less will be more sad, but rather the extent to which this recognition informs fairness judgments.”

My 10-year-old recently asked, unprompted, if her younger brother felt bad that her birthday present cost more. She wasn’t being performative—she genuinely felt the weight of being on the “advantaged” side of unequal distribution.

This age group can also understand “fair over time” concepts: “You got the bigger gift last year; this year it’s your brother’s turn” actually makes sense to them now.

What works at this stage:

Include them in fairness conversations. They’re ready to think through equity questions with you.

“What do you think would be fair here? Your brother really needs X for school, and you already have Y. How should we handle this?”

— Try saying this to ages 8-11

When I involve my older elementary kids in these discussions, they often come up with solutions I hadn’t considered—and they’re invested in making those solutions work.

Ages 12+: Equity and Context

Adolescents can fully understand all three fairness frameworks: equality (everyone gets the same), equity (those who contributed more get more), and need-based sharing (those who need more get more). Cross-cultural research shows these frameworks develop across cultures, though which type children prioritize varies by cultural context.

My teenagers can handle transparent family discussions about budget and priorities. They may still compare with siblings—that’s developmentally normal—but they can process complex reasoning about why gifts differ.

What works at this stage:

Collaborative decision-making and transparency.

“We have X budget this year. Let’s talk about what each of you needs most.”

— Try saying this to ages 12+

My 17-year-old recently advocated for her younger brother to get a bigger birthday gift than hers because “he’s really into this hobby right now and I don’t need anything specific.” That’s advanced fairness reasoning—and it started with years of conversations about fair versus equal.

The “That’s Not Fair!” Response Guide

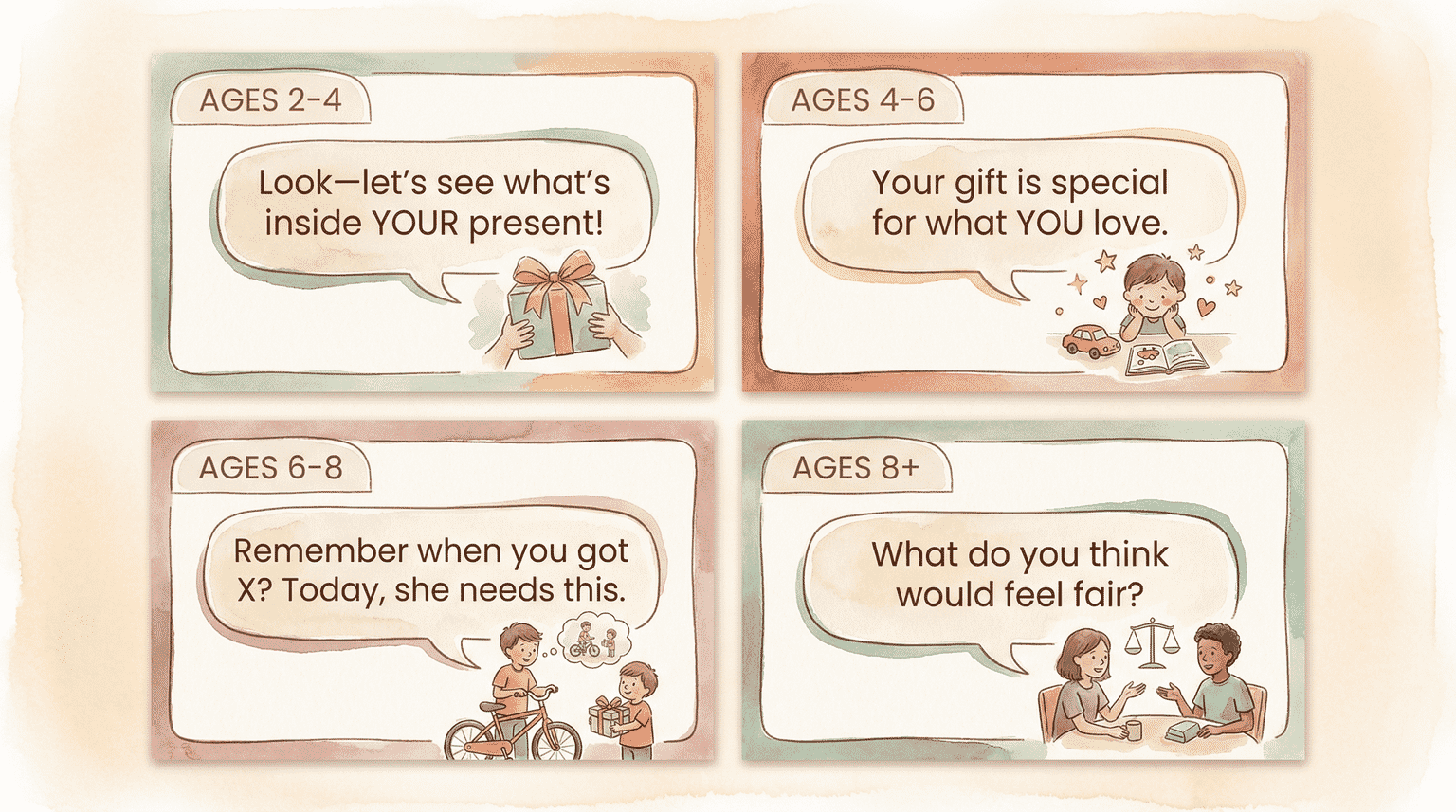

When the protest happens—and it will—your response should match their developmental stage.

For ages 2-4: Acknowledge feelings first, redirect attention.

“You feel upset. I hear you. Look—let’s see what’s inside YOUR present!”

For ages 4-6: Validate the feeling, offer simple explanation.

“I understand you noticed the difference. Your gift is special for what YOU love.”

For ages 6-8: Acknowledge, explain, connect to their experience.

“I can see that feels unfair. Remember when you got X for your birthday? That was bigger than what your sister got because you needed it. Today, she needs this.”

For ages 8+: Engage them in the reasoning.

“I hear that it feels unequal. Help me understand what would feel fair to you. What do you think we should consider?”

The research on sibling gift jealousy consistently shows that children whose feelings are acknowledged recover faster than those whose feelings are dismissed—even if the gift distribution doesn’t change.

This is one of the most powerful tools you have. Acknowledgment costs nothing and changes everything.

Setting Up Success Before Gift-Giving Events

The best complaint management is prevention. Here’s what works in my house:

Have the conversation early. Don’t wait until gifts are being opened to explain why they differ. A week before works well for most ages.

Visual equity matters for young children. Similar-sized packages, similar wrapping, similar number of items to unwrap. The perception of equality matters more than actual equality for kids under 6.

Brief extended family. Grandparents often default to strict equality, which can actually create problems if one child needs something specific. A quick conversation about your approach helps everyone stay aligned.

Separate the big gift. If one child is getting something significantly larger or more expensive, consider giving it separately—not in the group unwrapping context. This reduces direct comparison.

As the Frontiers for Young Minds researchers put it: try to “use these insights, see things from the other person’s perspective, and come to an agreement that takes everyone’s situation, needs, intentions, contributions, and sense of fairness into account.”

That’s a lot to ask of a 4-year-old. But it’s exactly what we’re building toward—one developmentally appropriate conversation at a time.

Frequently Asked Questions

At what age do children understand fairness?

Children show awareness of fairness by age 3 and will actively protest unequal treatment by age 4—a milestone observed across every culture studied. By age 5, they can explicitly judge distributions as “unfair.” The most significant shift comes around age 8, when children develop discomfort about receiving more than others and can understand context-based fairness.

How do you explain fair vs equal to a child?

For children under 6, keep it simple: “Fair means everyone gets what they need to grow.” For ages 6-8, use concrete examples: “You needed soccer cleats; your sister needed art supplies. Both are important for what you’re learning.” For older children, you can explain the three types of fairness: everyone gets the same, everyone gets based on effort, or everyone gets based on their needs.

Why does my child think everything is unfair?

Children’s brains are wired to detect inequality—it’s a protective mechanism. The brain regions processing fairness are the same ones processing anger and sadness, which is why unfair situations feel intensely personal. Additionally, self-control regions don’t fully mature until early adulthood, meaning children recognize unfairness before they can regulate their reactions.

Should siblings get equal birthday gifts?

Research suggests fair gifting—not strict equality—leads to better family outcomes. For children under 5, making gifts appear equal (similar package count and size) matters most. For children over 8, explaining why gifts appropriately differ based on age, interests, or needs typically produces better long-term family harmony than forced equality.

Your Turn

How do you explain “fair isn’t equal” in your house? I’ve found different scripts work for different ages—and some kids just need to hear it 47 times before it sinks in. What language has actually landed with your children?

I read every response—your fairness strategies help parents everywhere.

References

- Spark Interest with Sara – Harvard-informed framework for teaching fair vs. equal concepts to young children

- Frontiers for Young Minds – Research on cultural variations in children’s fairness perception and neural basis of fairness

- Frontiers in Psychology – 2022 study on developmental milestones in procedural and outcome-based fairness judgments

- PMC Developmental Psychology – Research on distributional justice and prosocial sharing development in children

- PMC Meta-Analysis – 2024 cross-cultural findings on inequity aversion in child development

Share Your Thoughts