Your 6-year-old hasn’t asked for a single toy you’ve ever heard of. Instead, every birthday wish involves products with names like “Squishy Surprise Mega Ultra” or “Fidget Pop Rainbow Explosion”—all discovered through some YouTube channel you didn’t know existed. When you ask where she saw it, she mentions a kid’s name like they’re old friends. They’re not. They have 50 million subscribers.

I’ve watched this pattern repeat across eight kids and fifteen years of parenting. My teenager remembers when YouTube was mostly cat videos. My toddler thinks iPads are just how we see the world. And somewhere in the middle, I’ve got kids at every stage of figuring out what’s real, what’s advertising, and why they need that thing they saw online.

Here’s what the research actually shows—and what I’ve learned navigating this with kids from ages 2 to 17.

Key Takeaways

- Children spend an average of 96 minutes daily on YouTube, with zero percent of child influencer content disclosing advertising

- Kids form real emotional bonds with influencers through parasocial relationships—making recommendations feel like advice from friends, not ads

- Children can identify ads around age 5, but don’t understand persuasive intent until ages 7-8

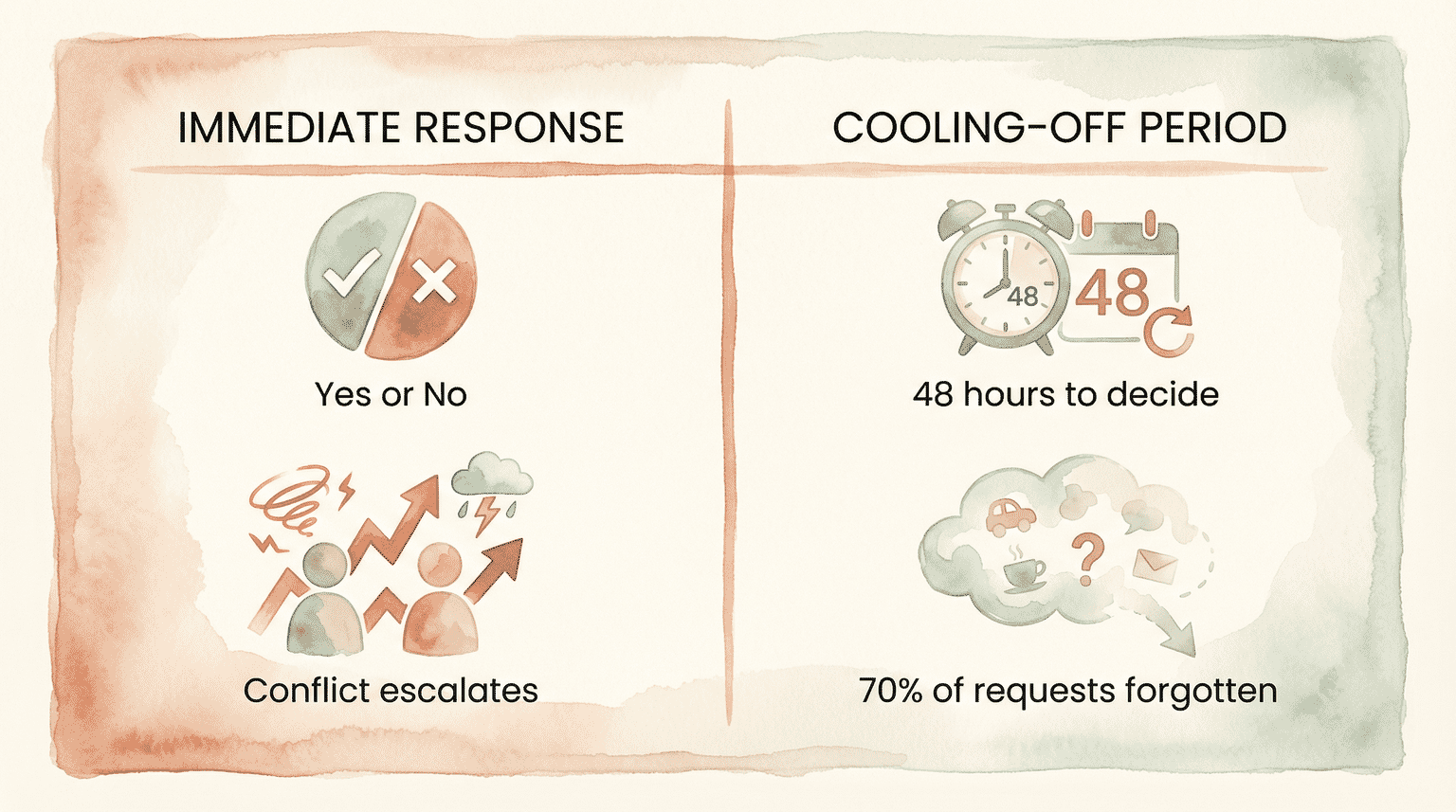

- A simple 48-hour cooling-off period causes about 70% of urgent gift requests to be completely forgotten

- Media literacy isn’t about restriction—it’s about building age-appropriate skepticism that transfers to other areas of life

Why This Generation Faces Something New

YouTube is now used by 63% of children globally for approximately 96 minutes daily. That’s not a typo. According to a 2025 study from the Journal of Business Research, the average child spends over an hour and a half every day on a single platform—and the top child influencer has over 123 million subscribers worldwide.

For context: that’s more than the population of most countries, all tuned in to watch one kid play with toys.

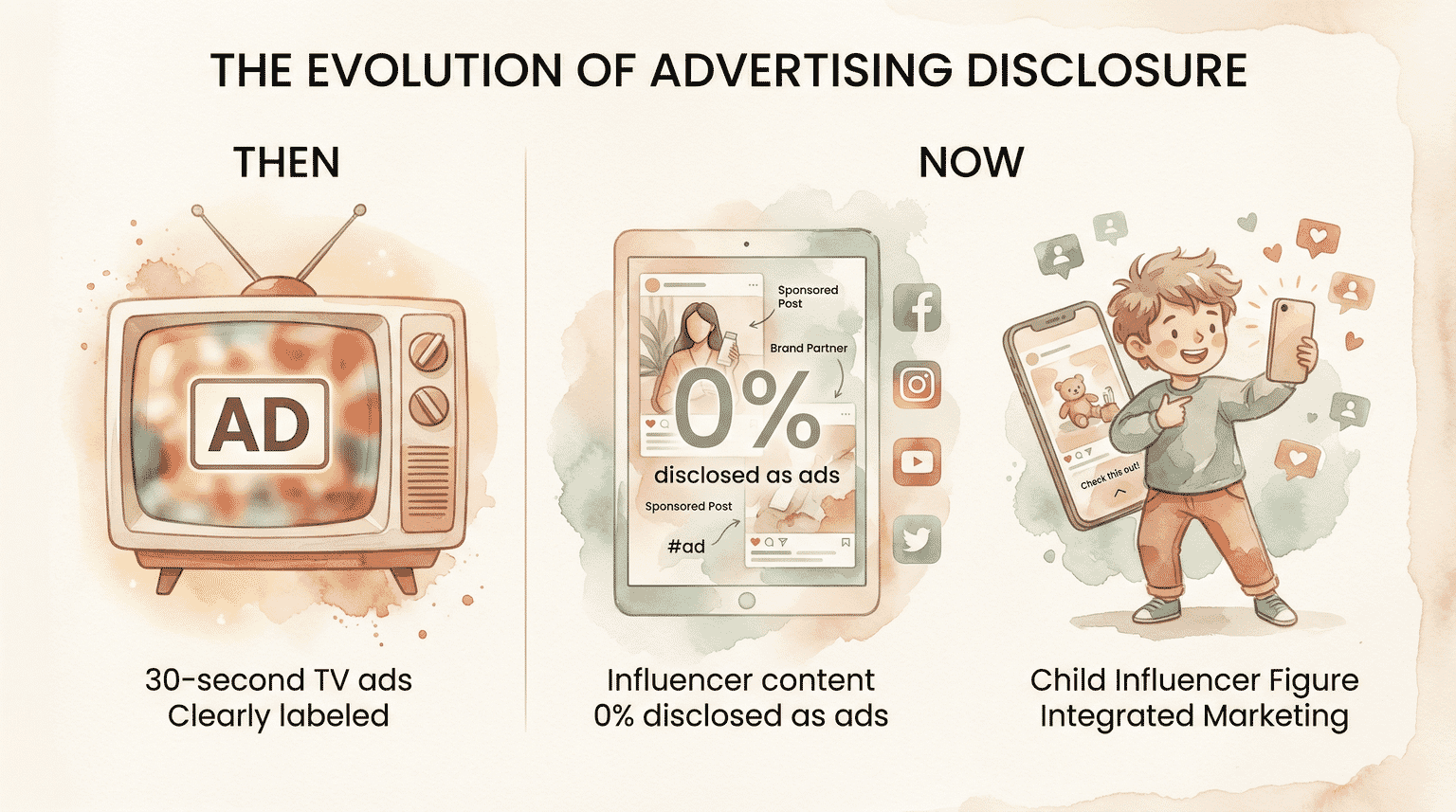

This isn’t the Saturday morning cartoon commercial of my childhood, where ads were clearly separated from shows and ran for 30 seconds. Today’s influence is woven into content so seamlessly that even adults struggle to identify it.

A 2024 NIH-published analysis of 162 YouTube videos from child influencers found that zero percent disclosed any content as advertising—no #ad tags, no sponsorship notes, nothing.

And here’s what really struck me: over half of Gen Z now say they want to be influencers, according to 2024 research. Only 1 in 6 wants to be a movie star. The influencer isn’t just selling toys—they’ve become the career model.

This matters for gift-giving because those wish lists didn’t come from nowhere. They came from hours of content specifically designed to make children want things, created by other children who feel like friends, delivered through algorithms that know exactly what keeps kids watching.

What’s Happening in Your Child’s Brain

When my 8-year-old tells me about “LilySophie” like she’s a classmate, she’s not confused—she’s experiencing something researchers call a parasocial relationship. These are one-sided emotional bonds where viewers feel genuine connection with people who don’t know they exist.

The Parasocial Relationship Effect

Children form these bonds because child influencers feel accessible in ways adult celebrities don’t. One 7-year-old participant in the Journal of Business Research study explained it perfectly: “They use children’s words, they explain things in an easy way. Sometimes, when a step is too complicated, they explain twice.”

This isn’t manipulation—it’s connection. The problem is that the higher the parasocial relationship, the greater the influencer’s ability to drive purchases. When your child’s “friend” recommends a toy, it doesn’t feel like advertising. It feels like advice.

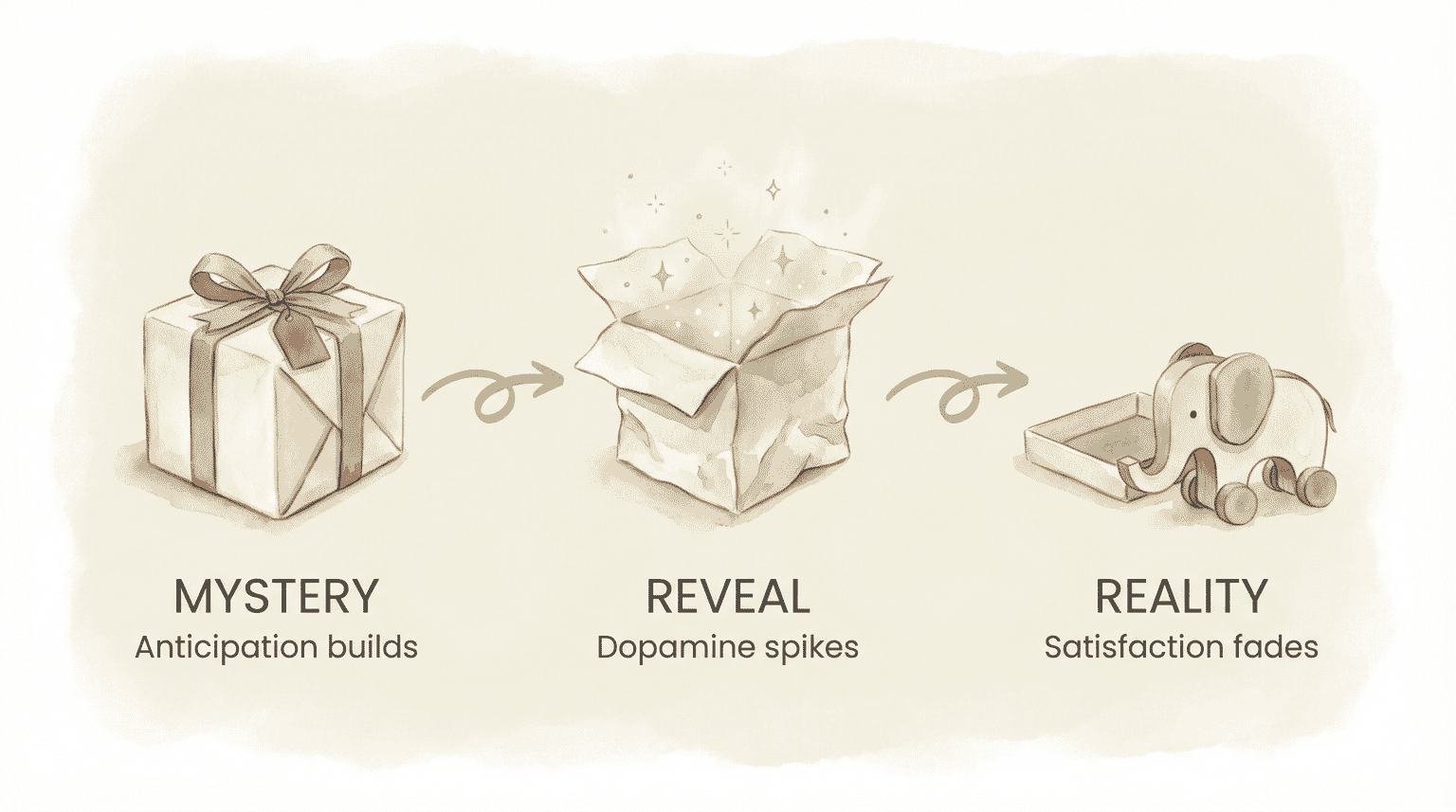

The Dopamine-Anticipation Loop

The moment before a box opens creates a neurological event. Variable rewards—where the outcome is uncertain and surprising—trigger stronger dopamine responses than predictable outcomes. This is why mystery boxes, blind bags, and unboxing reveals are so compelling.

My librarian brain had to dig into this one. Behavioral psychology research, going back to classic experiments, consistently shows that unpredictable rewards create a “discovery loop” that keeps us coming back. Add ASMR elements—the crinkle of packaging, the satisfying click of a lid—and you’ve got content that’s almost irresistible to developing brains.

This explains the “just one more video” phenomenon. It’s not a lack of willpower. It’s brain chemistry doing exactly what it evolved to do.

The Hidden Advertising Problem

The research on hidden influence reveals something troubling about how marketing reaches children today.

“The problem with these videos is that they send a strong message of consumerism. The central theme is that buying the promoted toy can bring unlimited happiness.”

— Dr. Kelli Burns, University of South Florida

That 2024 NIH study I mentioned found that 67% of food cues in child influencer content were classified as “not permitted” for marketing to children under WHO standards. Yet none of it was labeled as advertising.

The influencer content your child watches is marketing. It just doesn’t look, sound, or feel like marketing—which is exactly why it works.

Ages 2-4: The Pre-Advertising Comprehension Window

What’s Happening Developmentally

At this age, children literally cannot distinguish between content and advertising. According to Healthy Eating Research, children don’t begin discriminating between program and commercial content until approximately age 5.

My 2-year-old experiences screen content as direct communication. When someone on YouTube speaks to the camera, she waves back. When they hold up a toy, she reaches for it. The screen feels like a window to a friend’s house, not a stage for performance.

A 2023 study on children’s device usage found that 60% of US parents reported their child started using smartphones by age 5, with 31% indicating digital experiences before age 2. These are the years when repetition creates trust—when seeing something over and over means it must be important and good.

Exposure Patterns

At this stage, device use is primarily supervised entertainment. YouTube Kids is a common introduction point, and unboxing videos are particularly captivating because they combine anticipation, bright colors, and satisfying sounds—everything a toddler brain responds to.

In my house, I’ve watched my 2-year-old completely ignore a complex narrative cartoon but become transfixed by someone slowly opening a package. The psychology makes sense: she doesn’t need to follow a story. She just needs to watch something reveal itself.

Parent Strategies for This Age

Co-viewing is essential, not optional. This isn’t about policing content—it’s about providing context that a 2-4 year old can’t generate themselves.

What works in my house:

- Brief exposure with narration: “This is a video someone made about toys”

- Pausing to talk about what we see rather than letting content run continuously

- Redirecting to interactive content over passive consumption

- Focusing on limiting exposure rather than teaching recognition (they can’t recognize advertising yet anyway)

What to Say

Keep it simple and concrete:

“That’s a pretend show about toys.”

“Those people don’t know us—they’re making a video.”

“Let’s pause and talk about what we see.”

Ages 5-7: The Emerging Understanding Window

What’s Happening Developmentally

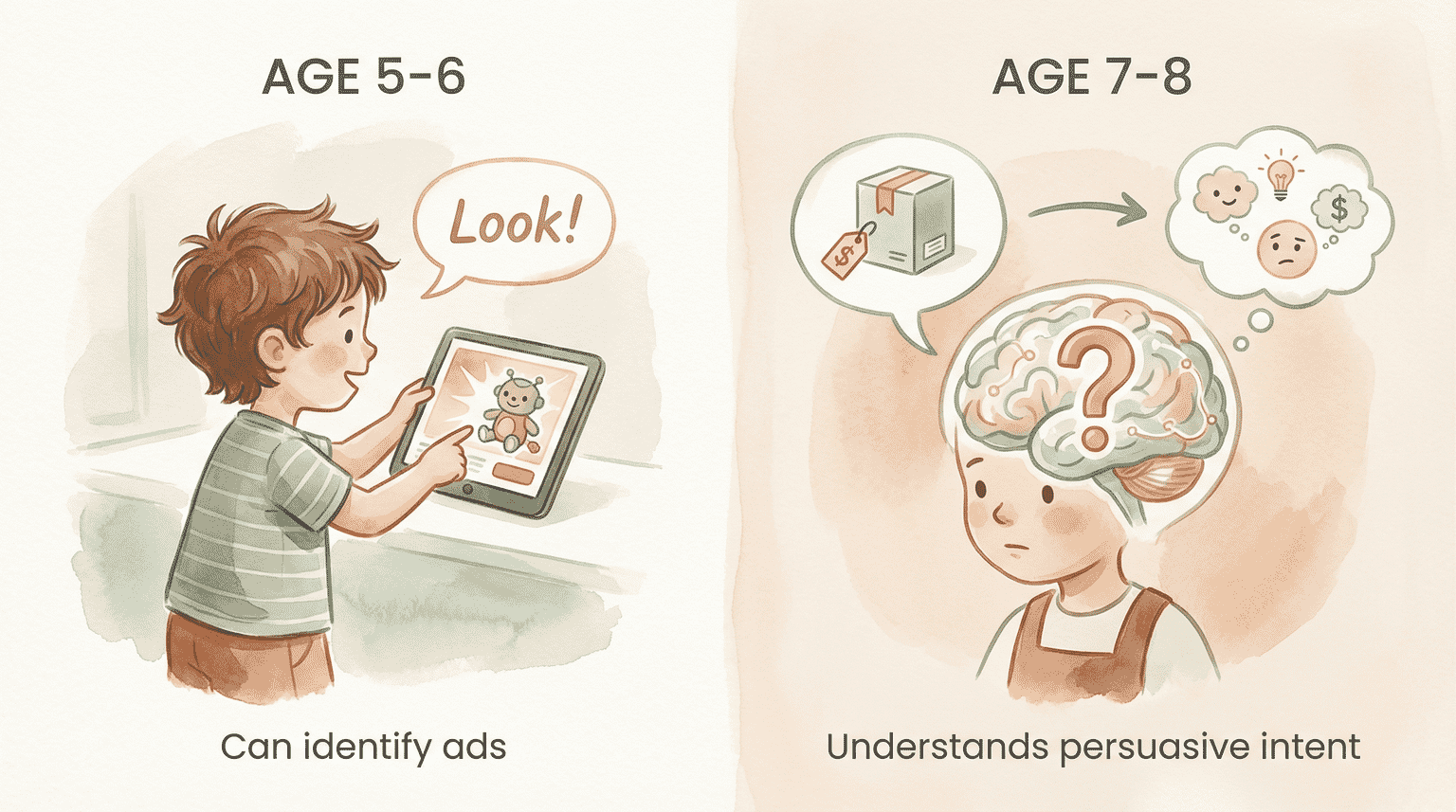

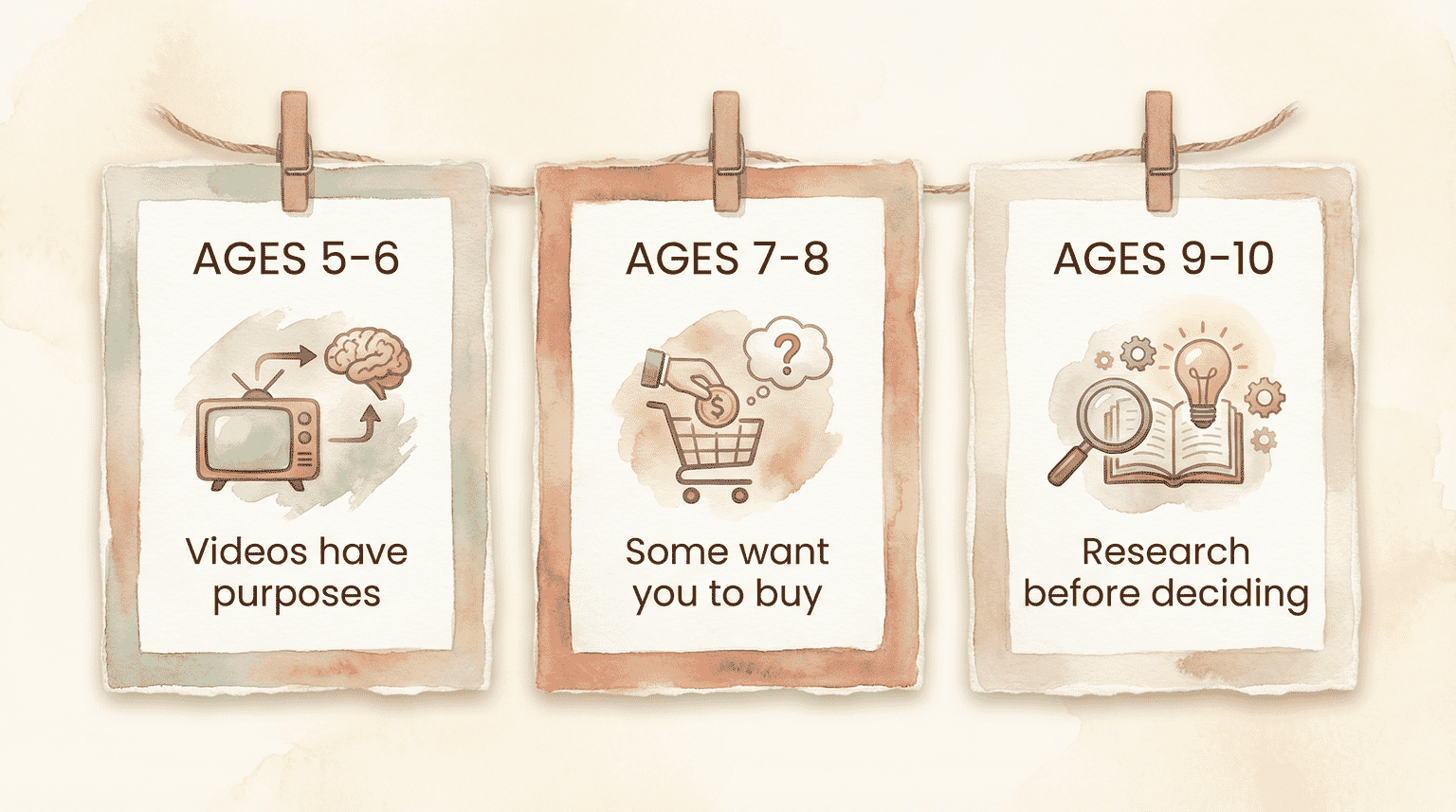

Around age 5, children begin to understand that advertising exists as a category. But here’s the critical gap: according to developmental research, they still cannot comprehend the persuasive intent of marketing until ages 7-8.

This means your 6-year-old might be able to point at a commercial and say “that’s an ad.” But she doesn’t understand that the ad’s purpose is to make her want something she didn’t want before. She doesn’t grasp that someone is strategically trying to change her mind.

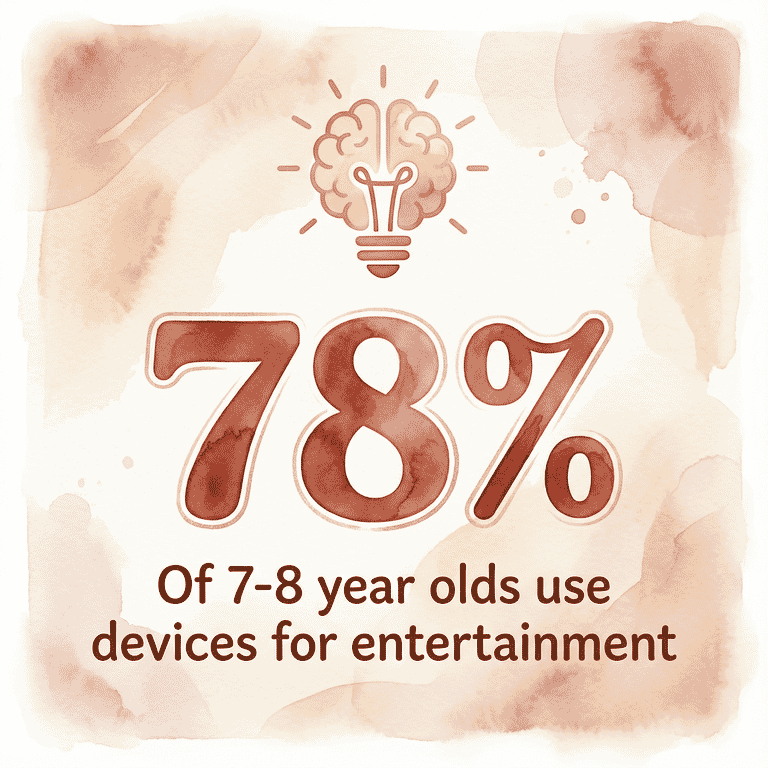

Research from the device usage study shows that children using devices as entertainment rises from 35.2% at ages 5-6 to 78% at ages 7-8. Meanwhile, peer influence begins compounding influencer exposure. Your child hears about viral toys at school from other kids who also watched the videos.

Vulnerability Factors

This age is particularly tricky because children seem more capable than they are:

- They can identify ads but don’t understand the purpose

- Influencer content still feels like friendship, not advertising

- Comparison culture emerges (“She has that toy, why don’t I?”)

- Birthday and holiday wishlists become increasingly influenced by screen content

Parent Strategies for This Age

This is when media literacy conversations begin, but gently:

- Ask questions while co-viewing: “Why do you think they’re showing us this toy?”

- Introduce the concept that videos have purposes beyond entertainment

- Set clear viewing limits with explanation, not just rules

When evaluating gift requests—and this is where we connect to the science behind meaningful gift-giving—start asking: “Is this because you saw it, or because you’d play with it?”

What to Say

“This person makes videos so you’ll want to buy things.”

“They get paid when you want that toy.”

“Do you think they’d show us if the toy broke?”

“Let’s see if there are reviews from regular kids.”

Gift-Giving Connection

This is the first age where you can meaningfully evaluate requests. In my house, we introduce a waiting period between seeing and requesting—usually 48 hours. You’d be amazed how many “must-have” toys are completely forgotten by Thursday if they were seen on Tuesday.

Ages 8-10: The Developing Critical Thinking Window

What’s Happening Developmentally

By age 8, children are developing genuine capacity for skepticism. The device usage research shows an important shift: usage evolves from pure entertainment to what researchers call a “psychological tool”—children begin using devices for communication, information-seeking, and homework, not just passive watching.

But there’s a concerning finding here too: higher frequency of digital device usage was significantly associated with lower scores in verbal working memory, inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility for 7-8 year-olds. The dose matters.

Here’s what surprised me in the research—and what I’ve seen with my own 8- and 10-year-olds: kids this age are more critical than we often assume.

In the Journal of Business Research study, one 9-year-old participant said: “Even if I could write a comment, probably she wouldn’t read it, she might be busy with the school stuff and the ideas for the videos.”

That’s sophisticated understanding—recognizing both the parasocial limitations and the reality behind influencer content. Children this age can acknowledge that influencers “sometimes exaggerate” and connect it to their own experience: “I sometimes exaggerate too.”

Build on this existing capacity rather than assuming passivity.

Parent Strategies for This Age

Engage in collaborative skepticism rather than top-down lecturing:

- “Let’s investigate this together”

- Discuss the business model: How do influencers actually make money?

- Connect to their own experience of exaggerating or performing

- Introduce the concept of algorithmic recommendation: “Why do you think you keep seeing similar videos?”

What to Say

“What do you think they’re not showing us?”

“If you were making money from this, what would you do?”

“Let’s look at what people who actually bought this say.”

“What would you do with this toy after the first day?”

Gift-Giving Connection

At this age, you can involve children in the research process:

- Teach price comparison and value assessment

- Discuss the difference between wanting and needing

- Create a collaborative wish list review process with categories: “definitely,” “maybe,” and “research needed”

This is where understanding common gift-giving challenges becomes genuinely collaborative.

Platform Comparison: YouTube vs. TikTok

Not all platforms work the same way on developing brains. Here’s what the research shows:

YouTube Characteristics

YouTube remains the giant: 63% of children use it globally, spending approximately 96 minutes daily. The longer-form content allows deeper engagement—and deeper parasocial relationships. Comments tend toward reflective conversations rather than quick reactions.

YouTube Kids exists as a curated alternative, though it’s not completely filtered from commercial influence. The platform is organized by age categories (preschool, younger 5-7, older 8-12), but advertising is still pervasive.

TikTok Characteristics

TikTok has captured younger audiences, though the platform has aged up—the largest user group is now 25-34 year-olds, with teens making up a significant but smaller share than at launch. The 15-60 second format creates different engagement patterns: quick emotional reactions rather than sustained attention. The algorithm is highly responsive to engagement, creating tight feedback loops.

Research from Universidad Villanueva found TikTok generates approximately 25 million total interactions with an average of 9,667 interactions per content piece. Comments focus on emotional reactions rather than reflective conversations.

What Parents Can Actually Control

Neither platform solves the advertising problem—and no parental control setting eliminates influence. What you can control:

- Time limits on both platforms

- Co-viewing when possible

- Conversation after viewing (this matters more than time limits alone)

- Content type awareness—knowing what your child is watching, not just how long

The Unboxing Video Phenomenon

If your child has ever begged for “just one more unboxing video,” you’re witnessing the dopamine-anticipation loop in real time.

The Psychology of Anticipation

Variable rewards—where the outcome is uncertain—are more stimulating than predictable ones. The moment of mystery before a package reveals its contents triggers a dopamine surge that predictable content simply doesn’t create.

Add the vicarious excitement of watching someone else experience a surprise, plus the ASMR elements (crinkling paper, satisfying sounds), and you have content specifically engineered for maximum engagement.

Why It’s More Powerful Than TV Commercials

The research on how unboxing videos affect children’s purchasing behavior tells us something important—with 78% of children regularly watching, the impact is nearly universal.

“Research shows that children are more likely to nag their parents for the advertised products after watching an unboxing video than if they watch a traditional TV commercial.”

— Josh Golin, Fairplay (formerly Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood)

The difference is format and relationship. An unboxing video might run 10-20 minutes—a full “experience” versus a 30-second spot. The child influencer feels like a friend making a recommendation, not an advertiser making a pitch. And it appears as entertainment, not commercial content. Building family gift traditions can help counterbalance this influence with meaningful rituals.

Parent Response Framework

Don’t dismiss the appeal—acknowledge it. Your child isn’t wrong that these videos are satisfying to watch. They are. The question is what happens next.

Use it as a teaching opportunity:

- Discuss anticipation versus ownership: “What happens after the unboxing moment ends?”

- Ask directly: “Do you want the toy, or do you want the unboxing experience?”

Practical Redirect

You can create unboxing experiences at home with existing toys. I’ve done this accidentally—wrapping up toys my kids already own and “surprising” them. The dopamine hit is similar because it’s the reveal that matters, not the novelty.

Slow down gift-opening for fuller experience. Focus on process rather than accumulation.

Managing Pester Power and Digital Wishlists

Research from the Children and Screens consortium confirms what every parent of an 8-year-old already knows: digital-era pester power is different from what previous generations experienced.

Why Digital-Era Requests Hit Different

The difference is frequency and reinforcement:

- Constant exposure versus occasional commercials

- Peer conversations amplifying influencer content

- Algorithms creating echo chambers of desire

- Request frequency correlating directly with viewing time

When my 10-year-old sees a toy once, she might mention it. When the algorithm shows her 47 videos featuring the same toy over a week, she campaigns for it.

The “Not Right Now” Framework

Avoid immediate yes or no responses when possible:

- Implement a cooling-off period (24-48 hours)

- Revisit the request with questions about sustained interest

- Track patterns: What requests persist versus fade?

In my house, I’ve noticed that about 70% of urgent requests are completely forgotten within a week if I simply say “let’s think about it.” That’s not me being clever—that’s the dopamine-anticipation loop completing its cycle without purchase.

The Wish List Review Process (By Age)

Ages 5-7: Parent curates with child input. You’re the editor.

Ages 8-10: Collaborative evaluation together. Introduce categories: “definitely,” “maybe,” “research needed.”

Scripts for Common Scenarios

“I really want the [TikTok toy]!”

Try: “Tell me what you’d do with it after the first day.”

“Everyone has one!”

Try: “Let’s see what you mean by ‘everyone.’ How many friends actually have it?”

“Can we get it RIGHT NOW?”

Try: “That’s not how our family decides about toys. Let’s add it to the list and talk about it this weekend.”

Communication with Gift-Giving Relatives

This connects to the broader challenge of managing gift expectations with extended family. Frame conversations around supporting your child’s development rather than restricting gifts. Provide alternatives when redirecting requests. A shared wish list system helps channel enthusiasm while maintaining quality standards.

This is one of many situations covered in understanding common gift-giving challenges.

Screen Gifts vs. Physical Gifts

With eight kids spanning every age, I’ve navigated the full spectrum of digital gift requests—from educational app subscriptions for my 6-year-old to gaming currency for my teenagers.

The Digital Gift Landscape

Digital gifts are real gifts now:

- Gaming subscriptions and app purchases

- Virtual items (skins, characters, accessories)

- Robux, V-Bucks, and virtual currencies

- Streaming access and educational platforms

Evaluation Framework

When evaluating digital gift requests, I ask:

- Does it extend screen time or create value within existing limits? A creative app used during already-allocated time is different from a subscription that adds hours of screen use.

- Does it encourage creation or passive consumption? Drawing apps and music creation tools differ from pure entertainment subscriptions.

- What’s the real-world connection or skill transfer?

- Is there social value with peers? Sometimes virtual currency enables social connection with friends.

When Digital Makes Sense

Digital gifts work well for:

- Educational content that supplements existing interests

- Creative tools (drawing apps, music creation)

- Social connection with family or friends at distance

When Physical Is Better

Choose physical when:

- Child is already at screen time limits

- Gift is meant to encourage offline activity

- Developmental benefits of tangible play apply

The research consistently shows that hands-on play develops different cognitive skills than screen-based interaction. For younger children especially, physical gifts often provide developmental benefits that digital alternatives don’t.

Instant Gratification and the Comparison Trap

The research on social media’s impact on young people reveals a troubling pattern that directly affects gift expectations.

“Too much social media time is associated with significant increased risk for depression, body dissatisfaction, social anxiety and upward social comparison.”

— Dr. Melissa Hunt, University of Pennsylvania

The Instant Gratification Cycle

Influencer content delivers immediate stimulation. The dopamine hit comes from wanting, not having—which is why satisfaction fades so quickly after acquisition. The same child who needed that toy watches it become forgotten within days.

Same-day delivery culture compounds the effect. When the gap between desire and possession shrinks to hours, delayed gratification never develops.

Children compare their toy collections to influencers who have unlimited access to new products. Peer conversations about influencer content reinforce the comparison. Researchers call this “upward social comparison”—measuring yourself against those who appear to have more.

The problem isn’t that your child wants things. It’s that the standard for “enough” becomes impossible to reach.

Breaking the Cycle

This connects to a values-based approach to gift-giving—focusing on what gifts mean rather than what they cost or how many exist.

Practical approaches:

- Gratitude practice with existing possessions

- Delayed gratification as a learnable skill (it genuinely is)

- Focus on use over acquisition

- Celebrating experiences, not just objects

Practical Tools

What works in my house:

- One-in-one-out policies: Something new means something old gets donated

- Waiting period requirements: Must still want it after 48 hours

- “Favorites” rotation: Instead of constant addition, we rotate what’s accessible

- Quality time over gift quantity

This is part of a larger pattern of breaking the consumer cycle that many families are navigating.

Building Long-Term Media Literacy

Media literacy isn’t about restriction—it’s about understanding. Children who understand influence are more resistant to it. And these skills transfer: the skepticism they develop about toy influencers will serve them when they encounter more sophisticated persuasion later.

Age-Appropriate Media Literacy Milestones

Ages 5-6: “Videos are made by people for reasons.”

Ages 7-8: “Some videos want you to buy things.”

Ages 9-10: “Here’s how to research before you decide.”

Conversation Starters by Development Stage

“What do you think they want us to feel?”

“Who made this, and why?”

“What’s the difference between a friend’s opinion and an influencer’s?”

“How can we find out if this is really as good as it looks?”

The Ongoing Process

This isn’t one conversation—it’s many, adapted over years as platforms evolve and children develop. Model skepticism yourself. Celebrate when your children notice manipulation. Admit when you’ve been influenced by advertising too.

I recently caught myself wanting a specific kitchen gadget after seeing it multiple times on social media. My 12-year-old pointed out the pattern. “Mom, you’re getting algorithm’d.” She was right.

When to Be Concerned

Most influence-driven behavior is normal. Children getting excited about influencer content, requesting featured products, feeling connection to online personalities—these are typical responses to designed experiences.

Normal vs. Concerning Patterns

Normal: Excitement about influencer content, requests for featured products, temporary disappointment when requests are denied.

Concerning: Distress when viewing is limited, identity fusion with influencer (“I AM like her”), inability to enjoy non-screen activities.

Warning Signs

Pay attention if you notice:

- Preference for parasocial relationships over real friendships

- Aggressive or persistent nagging far beyond typical requests

- Loss of interest in previous hobbies or toys

- Screen time negotiation dominating family interactions

When to Seek Support

If concerns persist after implementing strategies, or if other developmental areas seem affected, your pediatrician can provide guidance and referral if needed.

Frequently Asked Questions

At what age can children recognize YouTube ads?

Children begin distinguishing advertising from content around age 5, but research from Healthy Eating Research shows they don’t understand the persuasive intent of marketing until ages 7-8. This means even when children recognize something is an ad, they don’t understand its purpose is to make them want to buy products. Influencer content is especially challenging because it often doesn’t look like advertising at all—a 2024 NIH study found zero percent of 162 analyzed child influencer videos disclosed any content as advertising.

Why is my child obsessed with toy unboxing videos?

Unboxing videos trigger the brain’s dopamine-anticipation response through unpredictable rewards and mystery. Research in behavioral psychology shows variable (surprising) rewards create stronger engagement than predictable ones. Children also form “parasocial relationships”—one-sided emotional bonds—with influencers who feel like trusted friends. According to research from the Children and Screens consortium, children are more likely to nag for products after watching unboxing videos than after traditional TV commercials.

How do I talk to my child about influencers?

Start with age-appropriate explanations: for ages 5-7, explain “This person makes videos so you’ll want to buy things.” For ages 8-10, engage their existing skepticism by asking “What do you think they’re not showing us?” Research shows children already recognize some exaggeration—build on this existing critical capacity rather than assuming your child is passive.

Should I let my child watch YouTube Kids unsupervised?

YouTube Kids is curated but not completely filtered from commercial influence. Research shows advertising is pervasive across child-targeted content regardless of platform. For children under 7 who cannot understand persuasive intent, co-viewing remains important—not to police content, but to provide context. For ages 8-10, occasional unsupervised viewing with follow-up conversations can be appropriate.

What if grandparents keep buying whatever my child requests from TikTok?

Frame conversations around supporting your child’s development rather than restricting gifts. Share your family’s approach to evaluating requests and provide alternatives when redirecting. A shared wish list system helps channel enthusiasm while maintaining quality standards.

YouTube and TikTok influence children’s toy choices through three mechanisms: parasocial relationships (one-sided emotional bonds where influencers feel like trusted friends), the dopamine-driven anticipation of unboxing content, and peer-to-peer relatability that makes recommendations feel like advice rather than advertising. Research shows 63% of children globally use YouTube for approximately 96 minutes daily.

Join the Conversation

How has digital media changed gift-giving at your house? I’d love to hear your biggest challenges—and any strategies that have actually worked for navigating the YouTube-to-wishlist pipeline.

Your digital parenting wins might be exactly what another mom needs to hear.

References

- Child viewers’ engagement with social media influencers – Journal of Business Research study on YouTube usage statistics and children’s parasocial relationships with influencers

- Influencing children: food cues in YouTube content from child influencers – NIH-published research on hidden advertising in child influencer content

- Between Play and Exploitation: Child YouTubers – NIH research examining adult involvement and scripting in child YouTube content

- Voluntariness and type of digital device usage in children – Research on device usage patterns and cognitive impacts across age groups

- Kid Influencer Marketing: Gaps in Current Policies – Healthy Eating Research brief on developmental limitations in advertising comprehension

- The Influencer Impact: A Parent’s Guide – Children and Screens consortium research on influencer effects and parent strategies

Latest in Digital Gifts

-

TikTok Made Me Buy It: A Parent’s Quick Guide

by

· Updated

Continue reading →: TikTok Made Me Buy It: A Parent’s Quick GuideYour kid swears this viral product is different from the last three must-haves, and their urgency feels almost desperate. Science explains why their brain responds this way, plus a simple 4-question test to separate genuine wants from algorithm-driven impulses.

-

Ryan’s World Toy Marketing: How the Pipeline Works

by

· Updated

Continue reading →: Ryan’s World Toy Marketing: How the Pipeline WorksYour child can describe a toy in perfect detail before ever seeing it in a store. Here’s how the screen-to-shopping pipeline works and the five moments where you can actually interrupt it.

-

5 Ways to Reduce Your Child’s Unboxing Video Habit

by

· Updated

Continue reading →: 5 Ways to Reduce Your Child’s Unboxing Video HabitYour child’s brain is responding to unboxing videos the same way it would respond to a slot machine. Once you understand the psychology behind the pull, you can use these five strategies to break the cycle without the meltdowns.

-

Digital Pester Power: Why Kids’ Nagging Got Worse

by

· Updated

Continue reading →: Digital Pester Power: Why Kids’ Nagging Got WorseYour child saw a toy in a YouTube video three days ago and has asked about it fourteen times since. Here’s why digital nagging hits different than what our parents faced and the one technique that stops 70% of algorithm-driven requests.

-

Why Kids Can’t Wait: The Science of Patience

by

· Updated

Continue reading →: Why Kids Can’t Wait: The Science of PatienceYour 4-year-old isn’t being defiant when she melts down over waiting one minute for a cookie. Understanding the three brain mechanisms behind childhood impatience won’t stop every tantrum, but it will change how you respond to them.

-

When Your Child’s Friend Gets Better Gifts

by

· Updated

Continue reading →: When Your Child’s Friend Gets Better GiftsYour daughter comes home from the party quiet, and you know that look. It’s not about the iPad her friend got. Here’s what’s actually happening in her brain and the exact words that help.

Share Your Thoughts