You’ve just handed your 4-year-old an envelope containing a zoo membership. She tears it open, stares at the paper inside, and her face falls. “But where’s my present?”

I’ve watched this exact moment happen with three of my kids now. The first time, I thought my then-4-year-old was being ungrateful. By the third time, my librarian brain had kicked in and I’d researched what was actually going on.

Here’s what’s happening: young children think in concrete terms. As researchers at Baylor University explain, “concrete” means “that which is tangible; that which can be seen, touched, or experienced directly.” A zoo membership exists as an abstract promise of future fun—but your preschooler’s brain isn’t wired to process abstract promises yet. She needs something to hold.

The good news? There’s a systematic way to transform any experience gift into something young children can see, touch, and genuinely get excited about. I’ve used these strategies with my own kids (ages 2 through 17), and they work whether you’re giving swim lessons, concert tickets, or a trip to grandma’s house.

Key Takeaways

- Young children think concretely—they need something physical to hold before an experience feels real

- Visual countdowns bridge the gap between abstract “next week” and a child’s present-focused brain

- Physical souvenirs and photo books create lasting memory anchors that screens can’t replicate

- Anticipation timing matters by age: same-day for toddlers, up to 2 weeks for school-age kids

- A memory box transforms the anticipation items into a permanent “re-experiencing” tool

Strategy #1: Create a Tangible Representation

The first step is giving children something physical that represents the abstract experience. I call this the “anticipation box” approach, and it’s become standard practice in my house for any experience gift.

Research from Monash University (2022) found that concrete props create the conditions necessary for young children’s imagination to develop. The researchers observed toddlers aged 1.9-2.1 years and discovered that physical objects serve as “transitional objects” helping children move from reality into imagined scenarios. In other words, a stuffed penguin becomes a portal to the zoo trip that doesn’t exist yet.

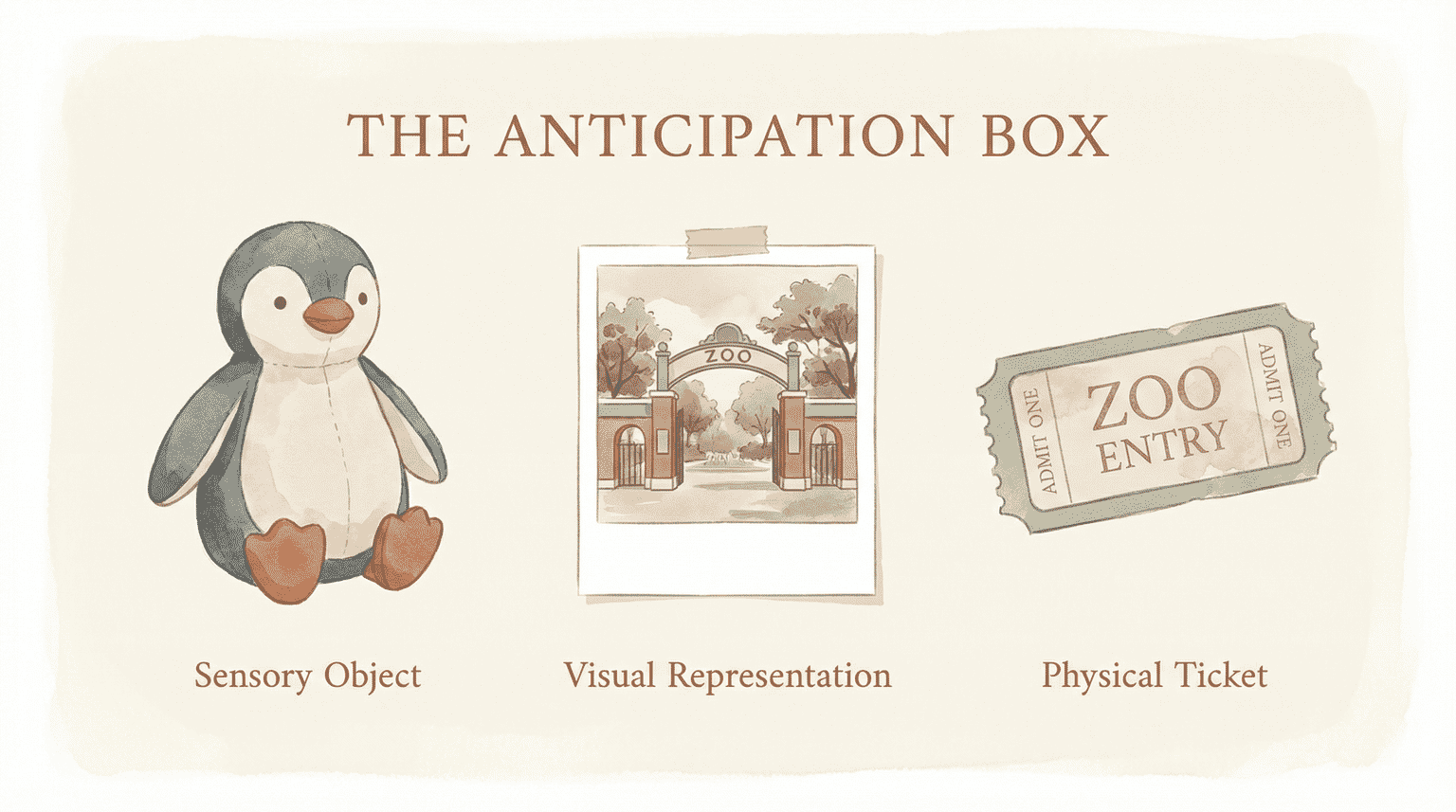

Your anticipation box should include:

- Visual representation: Printed photos of the destination, brochures, or drawings

- A related sensory object: A stuffed zoo animal for a zoo trip, a mixing spoon for a cooking class, binoculars for a nature hike

- The actual ticket or pass: Printed and visible, even if digital versions exist

For children under 5, the sensory object matters most—my 4-year-old clutched her stuffed flamingo for days before our zoo trip. Kids ages 6 and up respond well to maps, itineraries, and being involved in planning details.

My 8-year-old wanted to highlight our route on a printed zoo map, which made the experience feel real to her in a way the membership card never could.

Strategy #2: Build a Countdown Ritual

Young children live in the present. “Next Saturday” might as well be “next century” to a 3-year-old. A visual countdown bridges this gap by breaking an abstract timeline into something manageable.

According to constructivism research from UPI (2025), effective learning happens when tasks are broken into manageable steps with guided support—what researchers call “scaffolding.” A countdown ritual applies this same principle to anticipation-building.

Countdown mechanisms that work:

- Paper chain: One link removed per day (tactile and visual)

- Sticker calendar: Add a sticker each morning until the big day

- Sleep countdown: “Three more sleeps!” (best for younger children)

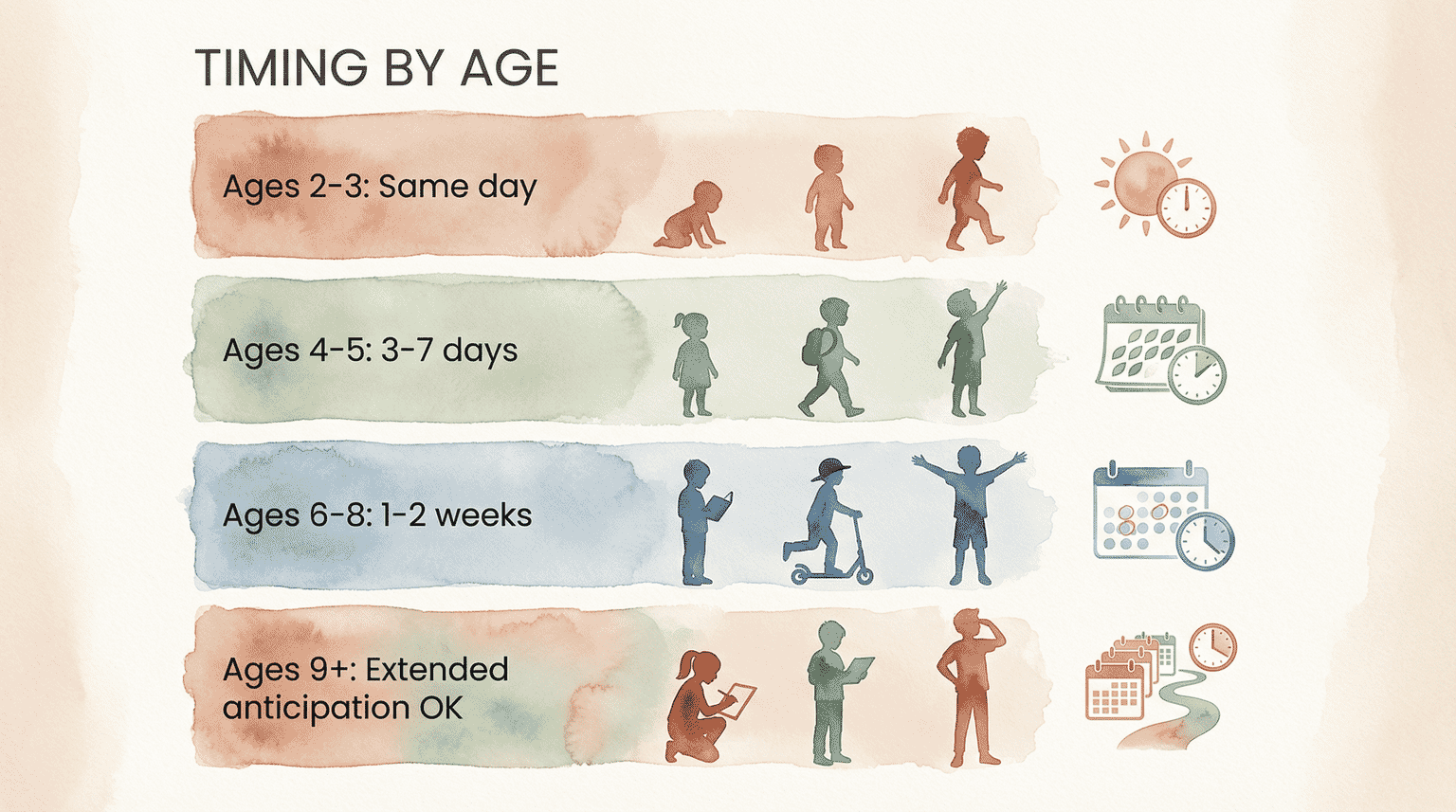

Timing matters by age:

- Ages 2-3: Same-day or next-day experiences work best

- Ages 4-5: 3-7 days maximum—longer waits feel endless

- Ages 6-8: 1-2 weeks with a visual countdown

- Ages 9+: Can handle extended anticipation and help research the experience

Pair the countdown with a daily ritual: one brief conversation about a single aspect of the upcoming experience. “What animal do you want to see first?” or “Should we pack snacks or buy them there?” This keeps the experience present without overwhelming a concrete thinker with too much abstract future.

Strategy #3: Anchor the Experience with Souvenirs

During the experience itself, your job is to help your child collect something tangible. This souvenir becomes what developmental psychologists call a “pivot object”—something physical that triggers memory recall long after the experience ends.

The NIH’s cognitive development research explains that children learn cause-and-effect through manipulating objects. From 6-12 months onward, learning happens through “reaching, inspecting, holding, mouthing, and dropping.” This hands-on pattern continues throughout early childhood—physical objects anchor abstract memories in ways that mental recall alone cannot.

This developmental milestone explains why physical souvenirs matter so much. The hands-on learning pattern that begins in infancy continues throughout early childhood.

Children’s brains are literally wired to process the world through touch and manipulation—which is why a smooth rock from the beach can trigger vivid memories years later.

Effective souvenirs include:

- Found objects: Shells, leaves, acorns, interesting rocks

- Ticket stubs and wristbands: The physical proof you were there

- Small purchased items: A postcard, a pressed penny, a simple toy from the gift shop

- Photos taken together: Especially ones the child helps choose

The collection process matters as much as what you collect. When my 6-year-old carefully selected three leaves to save from our nature hike, she was deepening her engagement with the experience itself. The leaves became more meaningful than any expensive souvenir because she’d chosen them.

Strategy #4: Document for Memory Building

Here’s something that surprised me: my kids almost never look at photos on my phone, but they return to physical photo books constantly. Dr. Kyle D. Pruett from the Yale Child Study Center explains why.

In a recent Psychology Today article (2025), he notes that “the rapidity with which the brain is growing makes it even more important to establish strong foundations” through concrete, interactive experiences rather than passive screen engagement.

A physical photo book becomes a “re-experiencing” tool—something your child can hold, flip through, and share with others.

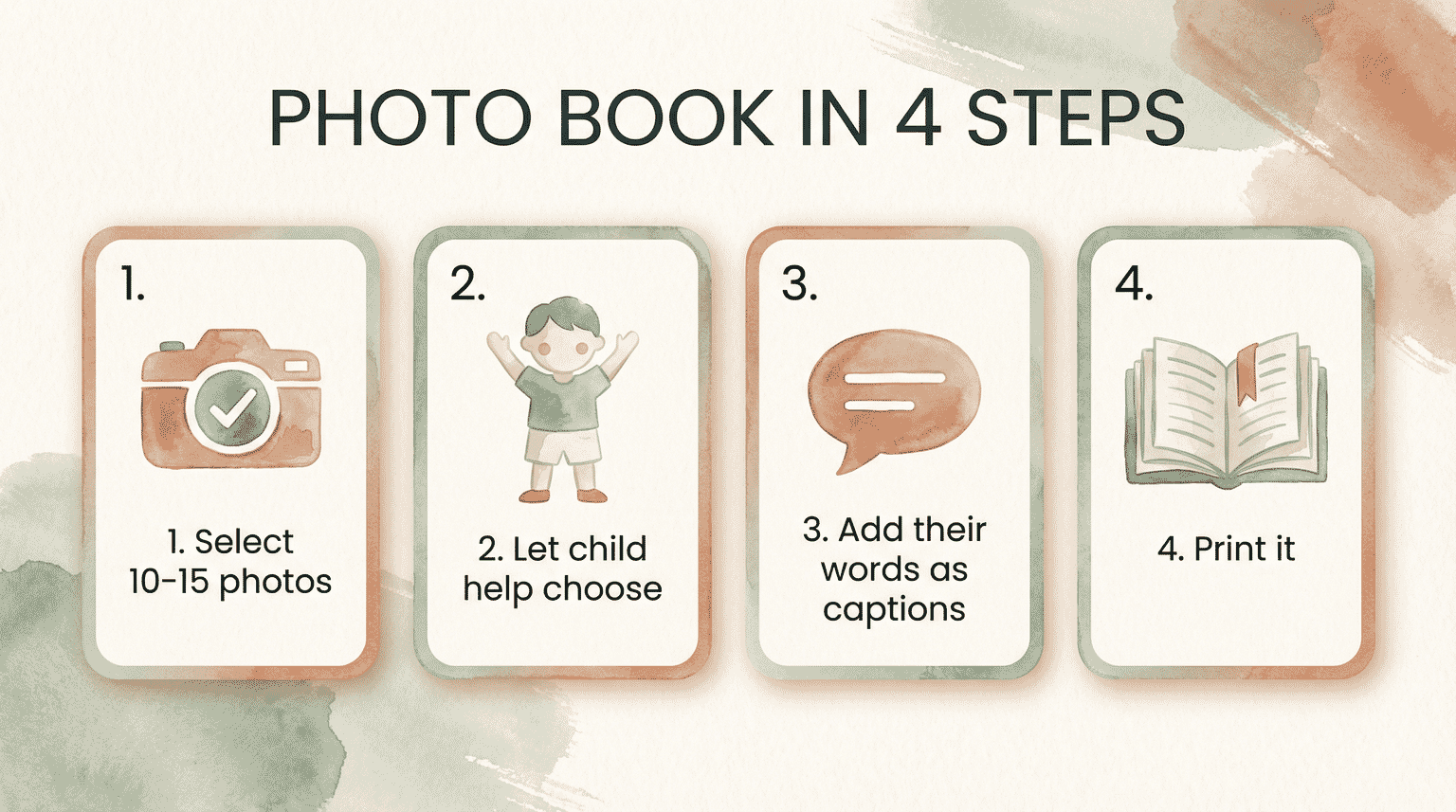

Photo book strategy:

- Select 10-15 photos maximum (too many overwhelms young children)

- Include your child in selection: “Which pictures should we keep?”

- Add simple captions in your child’s words: “I fed the goats and they tickled my hand”

- Print it. A tangible book beats a phone gallery every time

If you want to go deeper on creating photo books that capture experiences, I’ve written a whole guide on making them meaningful rather than just decorative.

Strategy #5: Tell the Story Together

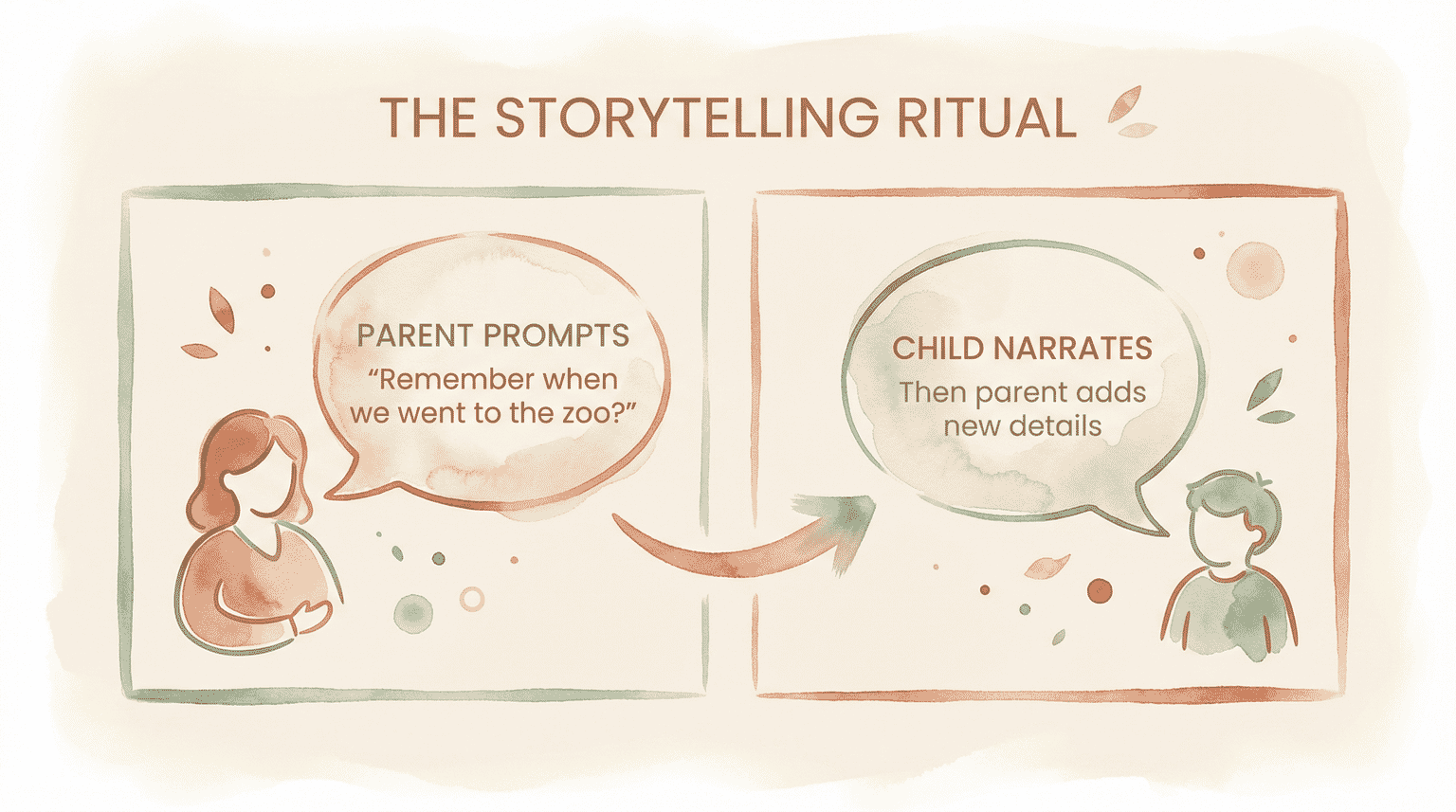

Memory consolidation happens through storytelling. Vygotsky’s foundational research established that “the more the child experiences, the more fertile the children’s imagination”—but experiences need to be processed through language to become lasting memories.

The three-part storytelling ritual:

This isn’t correcting your child’s memory—it’s enriching it. Each time you tell the story together, new details emerge and the experience becomes more solidly encoded.

Craft projects extend the experience further:

- Drawing favorite moments (even scribbles count)

- Creating a simple scrapbook page together

- Making something related (paper plate animals after a zoo trip, homemade trail mix after a hike)

When my kids understand why children often prefer toys to experiences in the moment, they’re more patient with younger siblings who need these concrete anchors.

Strategy #6: Create the Memory Box

The final strategy combines everything into a lasting keepsake. This is where the anticipation box transforms into something permanent.

What goes in the memory box:

- Original anticipation items (the stuffed animal, the brochures)

- Collected souvenirs from the experience

- Ticket stubs and wristbands

- Printed photos

- Your child’s artwork about the experience

- Written notes (what they said, funny moments, quotes)

The constructivism research confirms that children “understand concepts more easily when conveyed through direct experience and concrete media.” A memory box is concrete media for an abstract memory—something your child can return to and physically interact with.

Use it for regular “remember when” sessions. Pull out the box on a rainy afternoon, during a long car ride, or when siblings want to share what their experience was like. These moments of reminiscing strengthen the memory and create new shared experiences around the original one.

Quick Reference: Timing Guidelines by Age

| Age | Anticipation Period | Best Strategies | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-3 | Same-day or next-day | Immediate tangible representation, sensory object | They literally cannot conceptualize “next week” |

| 4-5 | 3-7 days | Visual countdown, symbolic object, daily ritual | Still concrete thinkers but can handle short waits |

| 6-8 | 1-2 weeks | Maps, itineraries, helping plan | Can engage with details and logistics |

| 9+ | Extended anticipation | Research participation, countdown ownership | Can handle and even enjoy the waiting |

This table gives you a quick snapshot, but remember: every child is different. Some 5-year-olds handle longer waits beautifully, while some 7-year-olds still need that tangible object to make it feel real.

From Abstract to Treasured

The experience gifts that initially confuse young children often become their most-referenced memories—but only when we give them concrete anchors along the way. That zoo membership my daughter didn’t understand? Three years later, she still pulls out her memory box and tells her younger brother about “the time the peacock chased Daddy.”

This connects to something bigger about the values behind what we give. Experience gifts aren’t just about avoiding toy clutter—they’re about creating shared memories that become part of your family’s story.

The anticipation box, the countdown, the souvenirs, the photo book, the storytelling, the memory box: together, they transform an abstract promise into something a young child can genuinely experience before, during, and long after the event itself.

My librarian brain finds this genuinely fascinating: we’re not tricking children into appreciating experiences. We’re translating experiences into the language their developing brains actually speak.

Frequently Asked Questions

How far in advance should I tell my child about an experience gift?

For children under 5, keep anticipation to 3-7 days maximum—longer waits feel endless to concrete thinkers who can’t yet grasp abstract time concepts. Ages 6-8 can handle 1-2 weeks with a visual countdown. Older children can engage with extended anticipation and even help research the experience.

What if my child is disappointed when they don’t unwrap a toy?

This reaction is completely normal for concrete thinkers—it’s not ingratitude, it’s brain development. Redirect attention immediately to the tangible items in the anticipation box: the related object, photos, and visible ticket. Start the countdown ritual right away to shift focus from what’s “missing” to what’s coming.

Do I need to buy expensive souvenirs during experiences?

Found objects often work better than purchased items for memory anchoring. Shells, leaves, ticket stubs, and even napkins from a special restaurant become powerful memory triggers. The collection process itself—choosing what to save—deepens engagement with the experience.

At what age can children appreciate gift cards for experiences?

Most children under 8 struggle with gift cards because they represent abstract future value. Even older children benefit from pairing gift cards with a tangible representation—a photo of the destination or a small related object that makes the promise feel real and immediate.

Over to You

What’s worked for making experience gifts feel exciting to young kids? I’d love to hear your presentation tricks—printable tickets, treasure hunts, or anything that’s helped avoid the “but where’s my present?” moment.

I read every response—your anticipation tricks could save another parent’s zoo membership moment.

References

- Monash University – Research on props and imagination development in toddlers

- Psychology Today / Yale Child Study Center – Concrete foundations for cognitive development

- NIH StatPearls – Comprehensive cognitive development milestones

- Edu Humaniora / UPI – Constructivism and concrete operational learning

- Baylor University – Piaget’s concrete operational stage research

Share Your Thoughts