Your 8-year-old wants the toy from the commercial. Your 12-year-old needs the shoes their friend has. Your teenager is convinced this one purchase will finally make them happy. Sound familiar?

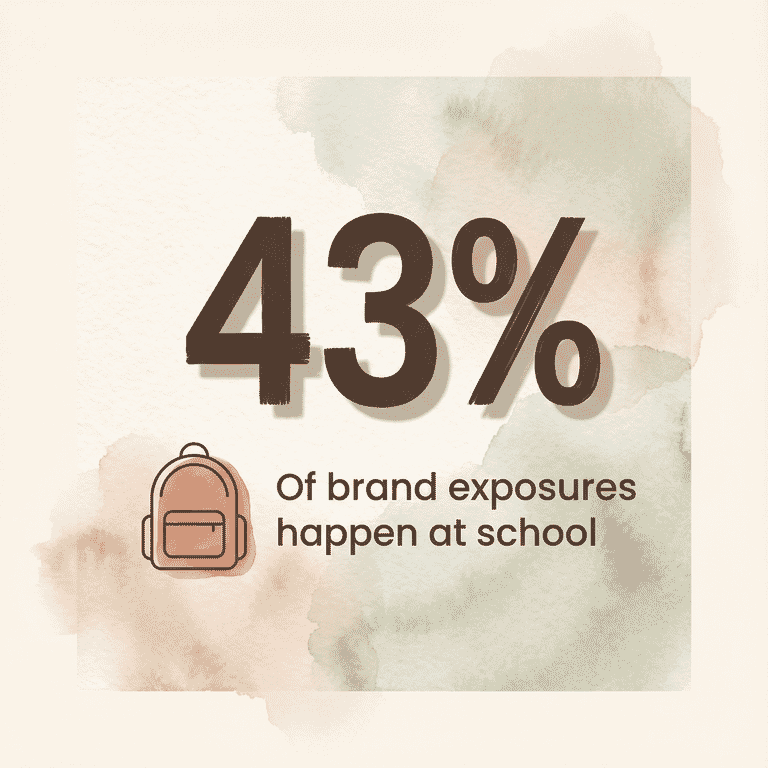

Here’s the thing: your kids aren’t broken. They’re responding normally to an abnormal environment. A 2022 study from The Lancet Planetary Health found that children ages 11-13 encounter 554 brand exposures per day—nearly one every minute they’re awake. And 43% of those exposures happen at school, not in front of the TV.

“Up until age 18, young people are highly vulnerable to advertising. They’re much more attuned to rewards, much less attentive to consequences and risks, much more tolerant of ambiguity, much more sensitive to social cues and much more impulsive.”

— Professor Connie Pechmann, UC Irvine’s Merage School of Business

You can’t eliminate consumer culture. But you can build resistance to it. Here are seven research-backed strategies—with specific scripts for what to actually say.

Key Takeaways

- Children encounter 554 brand exposures daily—teaching them to “Spot the Sell” builds critical awareness

- The 24-48 hour waiting period disrupts the automatic “see it, want it” response pattern

- Using material goods as rewards creates lasting materialism—prioritize experiences instead

- Materialism naturally peaks between ages 8-13 before declining, so some wanting is developmental

- What you model matters more than what you say—make your own thoughtful consumption visible

Strategy 1: Play “Spot the Sell”

The first step is helping your child recognize when someone’s trying to sell them something. This sounds obvious to adults, but children under 8 view advertising as informative, truthful, and entertaining. They genuinely don’t understand it has an agenda.

The technique: Turn ad-spotting into a game. When you’re watching TV, scrolling through YouTube, or walking through a store, challenge your kids to identify: “Who’s trying to sell us something right now?”

What to say: “Let’s play Spot the Sell! Every time you see something trying to get us to buy, point it out. Ads, logos, influencers holding products—all of it counts.”

Research on media literacy interventions shows this works remarkably well—with an effect size of d = 1.12 for improving children’s knowledge about advertising tactics. That’s a large effect in educational research terms.

The OT Environmental Action analysis puts this in perspective: the childhood marketing sector spends $130 billion annually targeting your kids. Ninety-seven percent of American children under 6 already own something featuring media character imagery.

Teaching them to see the sell isn’t paranoid—it’s practical.

A note on age: Children around 7-8 can learn “this is an ad,” but they won’t automatically resist until later. Don’t expect the game alone to stop the wanting. It’s building a foundation.

Strategy 2: Implement the Waiting Period

Here’s what foundational habit research tells us: information campaigns alone don’t change behavior. A meta-analysis of 110 media interventions found that during campaigns, viewers’ substance abuse levels actually increased even as their attitudes became more negative. Knowing better doesn’t automatically mean doing better.

The same applies to wanting stuff. You can explain why your child doesn’t need something, and they’ll still want it. What works better is disrupting the automatic response pattern.

The technique: When your child asks for something, don’t say yes or no immediately. Add it to a “thinking list” and revisit in 24-48 hours.

What to say: “That looks cool. Let’s add it to your thinking list and talk about it tomorrow. If you still want it then, we can figure out a plan.”

This isn’t a stalling tactic (though it works as one). It’s breaking the stimulus-response loop. Research on habit formation shows approximately 45% of everyday actions are habits performed in the same location daily. Creating space between “see thing” and “want thing” disrupts the automatic pathway.

The follow-up technique: When you revisit, ask: “Why do you think they want you to want this?”

What to say: “So you’ve been thinking about that toy for two days—it’s clearly something you really want. Here’s my question: why do you think the company wants you to want it? What are they hoping you’ll feel?”

This moves from passive recognition to active critical thinking. For more on building gift values in your family, this question becomes a cornerstone conversation.

Strategy 3: Address the Belonging Problem Directly

“But everyone has it.”

If you have a child between 8 and 16, you’ve heard this. And here’s the uncomfortable truth from research published in PMC: they’re not entirely wrong to care.

The study found that teens follow influencers to “reinforce their sense of belonging.” The desire to feel normal is, as the researchers describe it, “an obsession that haunts the majority of teenagers.” They’ll do almost anything—even things they know are unwise—to avoid social rejection.

You can’t argue a child out of wanting to belong. But you can address the belonging need so that material goods aren’t the only solution.

The technique: Acknowledge the belonging need first. Then redirect the source.

When your child says: “Everyone at school has these shoes.”

Try: “It’s hard to be the only one without something. That feeling of wanting to fit in is real—I get it. Let’s think about this: what else makes you feel like you belong with your friends? What do you guys actually do together?”

The goal isn’t to dismiss their feelings as shallow. The goal is to help them see that belonging comes from shared experiences, interests, and connection—not just shared stuff.

Build identity around interests, not items. When you notice your child lighting up about something they do—soccer, drawing, coding, reading a particular series—invest your attention there. A child with a strong sense of “I’m the kid who’s really into marine biology” is less likely to need “I’m the kid who has the newest phone” for identity.

This connects to the broader work of creating a complete family gift philosophy—defining what your family values beyond consumption.

Strategy 4: Reinforce Alternative Values

Here’s a finding that stopped me cold: research from the Journal of the Association for Consumer Research (2024) found that parents who use material goods as rewards or punishments create higher materialism in their children that persists into adulthood.

Read that again. The “if you get good grades, I’ll buy you…” approach backfires long-term.

The same research shows materialism and self-esteem follow inverse patterns in children. As one rises, the other falls. So building self-esteem through non-material means isn’t just nice—it’s protective.

The technique: Prioritize experiences over items in celebrations and rewards.

What to say: “You worked so hard on that project! Let’s celebrate—what should we do? Movie night with your pick? Trip to the trampoline park? Special breakfast, just the two of us?”

Notice the options are all experiences, not purchases. You’re reinforcing that achievement deserves celebration—but the celebration is about doing, not acquiring.

The gratitude technique: Keep this simple. You don’t need an elaborate gratitude journal system. Just ask at dinner: “What’s something good that happened today?” or “What’s something you’re glad about right now?”

Research shows intrinsic goals (relationships, self-actualization, physical health) aid subjective wellbeing, while extrinsic goals (wealth, image, social recognition) prove counterproductive. Gratitude practice nudges attention toward intrinsic satisfactions.

For families navigating digital spaces where much consumer pressure originates, navigating digital gift culture offers additional strategies.

Strategy 5: Model Thoughtful Consumption

I’d love to tell you that what you say to your kids matters most. But research on intergenerational influence tells a different story: children learn consumption patterns by watching what you do.

Studies on sustainable behavior transmission found stronger effect sizes for visible behaviors compared to invisible ones. Families have more opportunities to learn from each other during visible activities.

The technique: Make your own decision-making process visible.

What to say (while shopping): “Hmm, I like this, but I’m going to think about it. I don’t want to buy something just because it’s on sale—I want to make sure I’ll actually use it.”

Or: “I’ve been wanting one of these for a while. I’m going to wait until next month and see if I still want it.”

Your kids are watching. When you demonstrate waiting, questioning, and choosing intentionally, you’re teaching more than any lecture could.

Strategy 6: Calibrate to Their Age

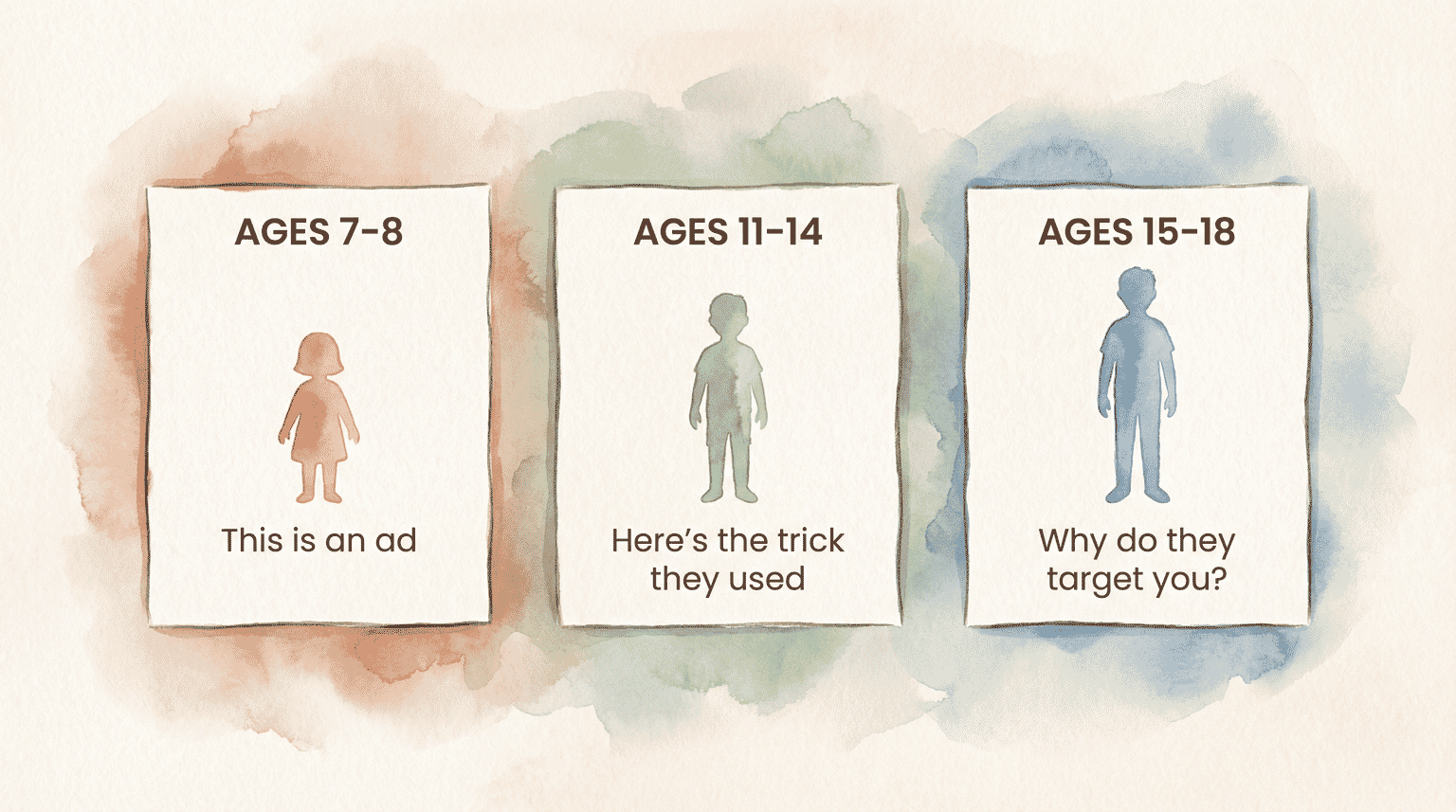

Professor Pechmann’s research offers crucial guidance: “If someone is 7 or 8 years old, you can’t teach them the same thing as if they’re 17. When they’re 17, you can talk about tobacco companies targeting them. When they’re 7, you can teach them there’s such a thing as an ad that tries to persuade them.”

Here’s what developmental research tells us about calibrating your approach:

Ages 7-8: Children begin understanding that ads try to persuade, but won’t automatically apply this knowledge. Focus on recognition: “This is an ad. It wants you to feel something.”

Ages 11-14: Knowledge of specific advertising tactics develops. You can discuss techniques: “See how they used that music to make you feel excited? That’s called emotional appeal.”

Ages 15-18: Abstract thinking allows for bigger-picture conversations. “Why do you think companies spend so much targeting teenagers specifically? What does that tell you about their view of you?”

One thing that doesn’t work across any age: focusing on long-term consequences. Pechmann notes, “Young people don’t expect to live to be 70 years old. They think middle age is 30 or 40, so it doesn’t work to talk about the long-term effects.”

What does work? Social acceptability. Youth want immediate rewards but don’t want immediate rejection for being “uncool.”

When Strategies Don’t Work Immediately

If you’ve tried these strategies and your child still wants everything, take a breath. You’re not failing.

Here’s what’s happening: researchers call it the “hedonic treadmill.” New acquisitions become the new baseline, ceasing to evoke positive emotions, which drives incessant demand for more. This is normal human psychology, not a character flaw in your child.

Also normal: materialism naturally peaks between ages 8-13 before declining. The wanting is partly developmental. It will ease.

Research on habit change found that 36% of successful change attempts involved moving to a new location, compared to only 13% of unsuccessful attempts. Sometimes environmental change is more powerful than conversation.

This might mean:

- Changing routes to avoid trigger stores

- Adjusting screen time or content

- Shifting social activities toward experiences

- Rearranging physical spaces to reduce exposure

Signs you’re making progress:

- Your child notices ads without prompting

- The waiting period becomes normal, not a battle

- They start asking “why do they want me to want this?”

- Experiences get mentioned alongside (or instead of) stuff in wish lists

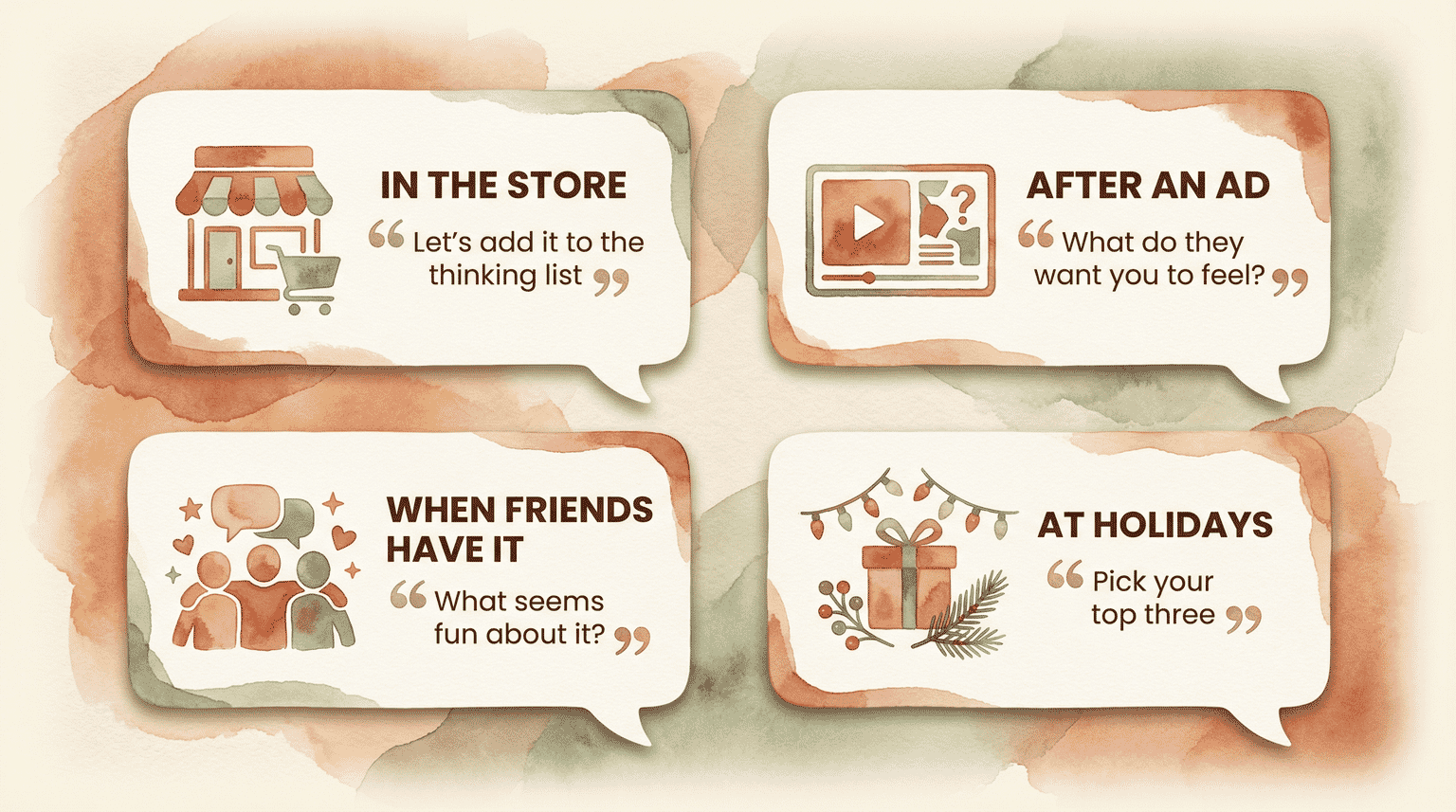

Quick Reference: What to Say

In the store:

“That’s interesting. Let’s add it to the thinking list and decide later when we’re not surrounded by things designed to make us want to buy.”

After seeing an ad:

“What do you think they want you to feel right now? What do they want you to do?”

When friends have something new:

“It makes sense you’d want that—your friend seems excited about it. What is it about the thing that seems fun to you? Is there another way to get that kind of fun?”

At birthdays/holidays:

“If you could only pick three things, which would matter most? Let’s focus on those.”

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I stop my child from wanting everything they see?

You can’t eliminate wanting—children encounter nearly 554 brand exposures daily and are neurologically wired to respond to rewards. Instead, implement the “Waiting Period” protocol: respond to requests with “Let’s add it to your thinking list” and revisit in 24-48 hours. This disrupts the automatic stimulus-response pattern and significantly reduces impulse requests.

At what age do children understand advertising?

Around ages 7-8, children begin understanding that ads try to persuade them. However, this knowledge doesn’t translate to automatic resistance—that develops later, around ages 11-14, when children start recognizing specific advertising tactics. As Professor Pechmann notes, “When they’re 7, you can teach them there’s such a thing as an ad. When they’re 17, you can talk about companies targeting them.”

How do I deal with a materialistic child?

Materialism naturally peaks between ages 8-13 before declining, so some wanting is developmental. The most effective responses: avoid using material goods as rewards or punishments (research shows this creates lasting materialism into adulthood), address belonging needs through connection and experiences, and model thoughtful consumption yourself.

How does consumerism affect child development?

Research shows materialism and self-esteem follow inverse patterns—as one rises, the other falls. Children with stronger consumer involvement show poorer relationships with parents, and the hedonic treadmill means acquisitions quickly stop providing satisfaction. The $130 billion childhood marketing industry targets children precisely because their developing brains are more attuned to rewards and less attentive to consequences.

Over to You

How do you push back against consumer culture in your family? I’d love to hear what’s worked—and whether your kids have started noticing marketing tactics on their own.

I read every comment—your anti-consumerism wins give me hope and ideas.

References

- The Lancet Planetary Health Study (2022) – Objective measurement of children’s daily brand exposure

- PMC Social Media Influencers Study (2023) – Psychological mechanisms of social media influence on teenagers

- OT Environmental Action Analysis (2024) – Impact of consumer culture on pediatric health and development

- Journal of Media Literacy Education – Meta-analysis of media literacy intervention effectiveness

- UCI Merage School of Business (2024) – Professor Pechmann’s research on children and advertising vulnerability

- Journal of the Association for Consumer Research (2024) – Developmental patterns of materialism and consumer behavior in children

Share Your Thoughts