Your six-year-old has never seen a commercial for it. You’ve never mentioned it. Yet suddenly, desperately, she needs a $400 electric scooter with LED wheels that some YouTuber unboxed last Tuesday. She can describe features you’ve never heard of. She knows it comes in teal.

This isn’t random. And it isn’t just “kids wanting things.” What we’re witnessing is the most sophisticated persuasion technology ever deployed—and children are its most receptive audience.

My librarian brain couldn’t let this one go. After watching eight kids suddenly “discover” toys I’d never heard of, I started digging into the research. What I found explains not just why your child wants what they want, but how platforms are systematically engineering those desires.

Key Takeaways

- Children cannot understand algorithmic manipulation until early adolescence—they trust recommendations as neutral discoveries

- Nearly half of recommended video thumbnails show “lavish excess and wish fulfillment”—luxury items designed to trigger wanting

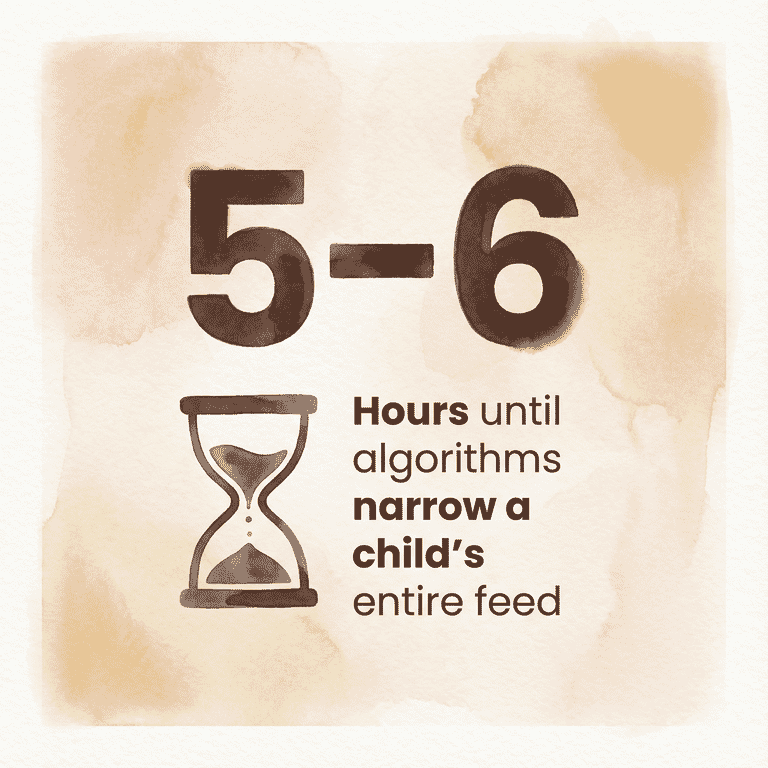

- After just 5-6 hours on platform, algorithms narrow a child’s entire feed based on predicted preferences

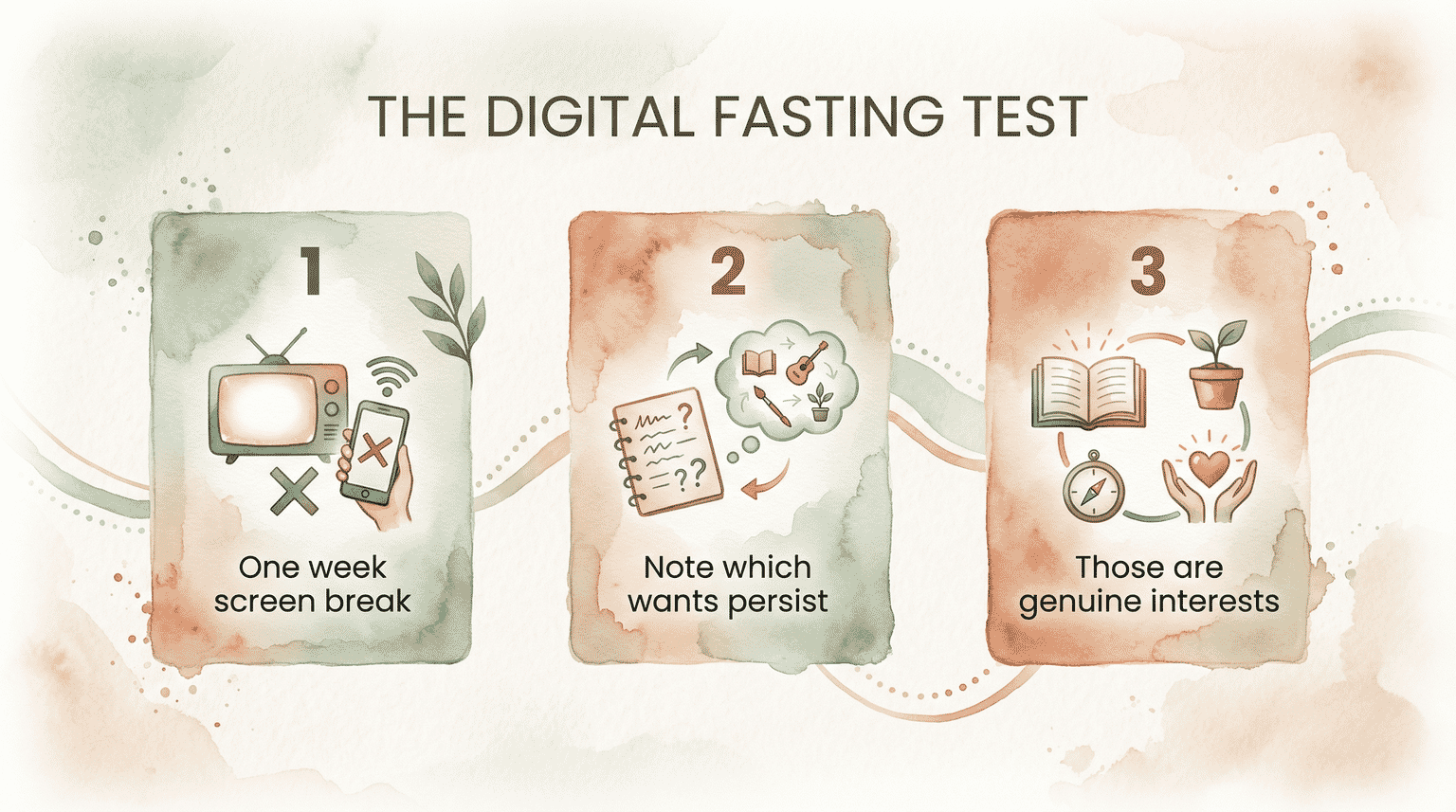

- The “digital fasting test” reveals which desires are genuine: interests that persist after a week without screens are real

- Co-viewing and asking “why do you think you’re seeing this?” helps children develop awareness they can’t develop alone

What Happens When Your Child Opens YouTube?

Here’s what the research actually shows: when a child searches for something innocent—Minecraft tutorials, Roblox gameplay, MrBeast videos—an automated system immediately begins curating their experience. University of Michigan researchers analyzing 2,880 video thumbnails found these recommendations aren’t random. They’re designed with surgical precision.

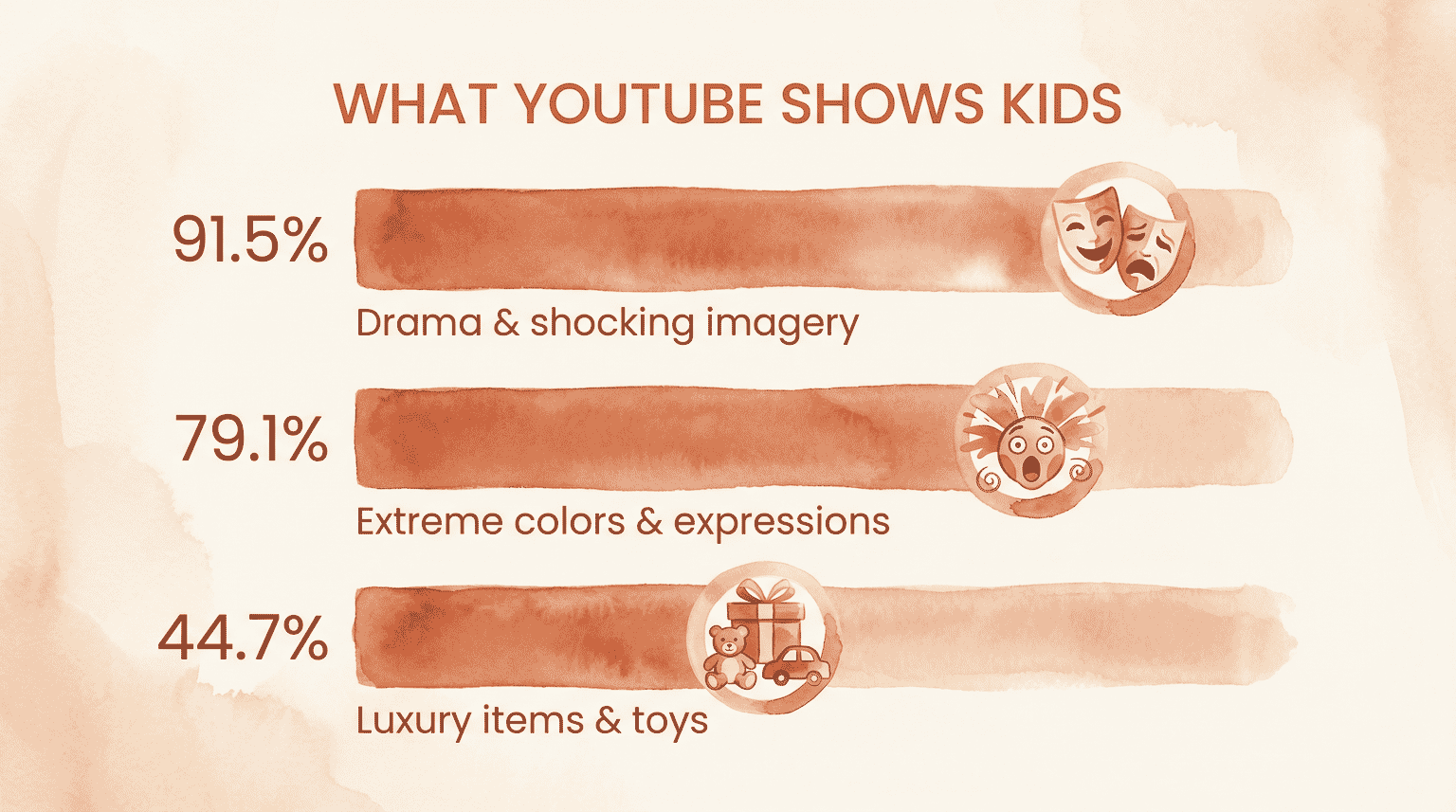

91.5% of thumbnails contained “drama and intrigue”—shocking imagery designed to make kids click. 79.1% featured “visual loudness”—extreme colors, exaggerated facial expressions, exclamation points everywhere.

And here’s the finding that stopped me cold: 44.7% showed “lavish excess and wish fulfillment”—luxury items, money, and toys children can’t possibly have.

That last category is doing more work than parents realize. Every time your child sees a thumbnail featuring expensive toys, dream bedrooms, or mountains of unboxing hauls, their brain receives a message: this is what you should want.

The platforms aren’t neutral. Hundreds of hours of content upload every minute. Humans don’t review most videos before children see them—automated systems decide what your child sees next. And those systems optimize for one thing: keeping eyes on screens.

How Each Platform Reads Your Child

Different platforms engineer desire differently.

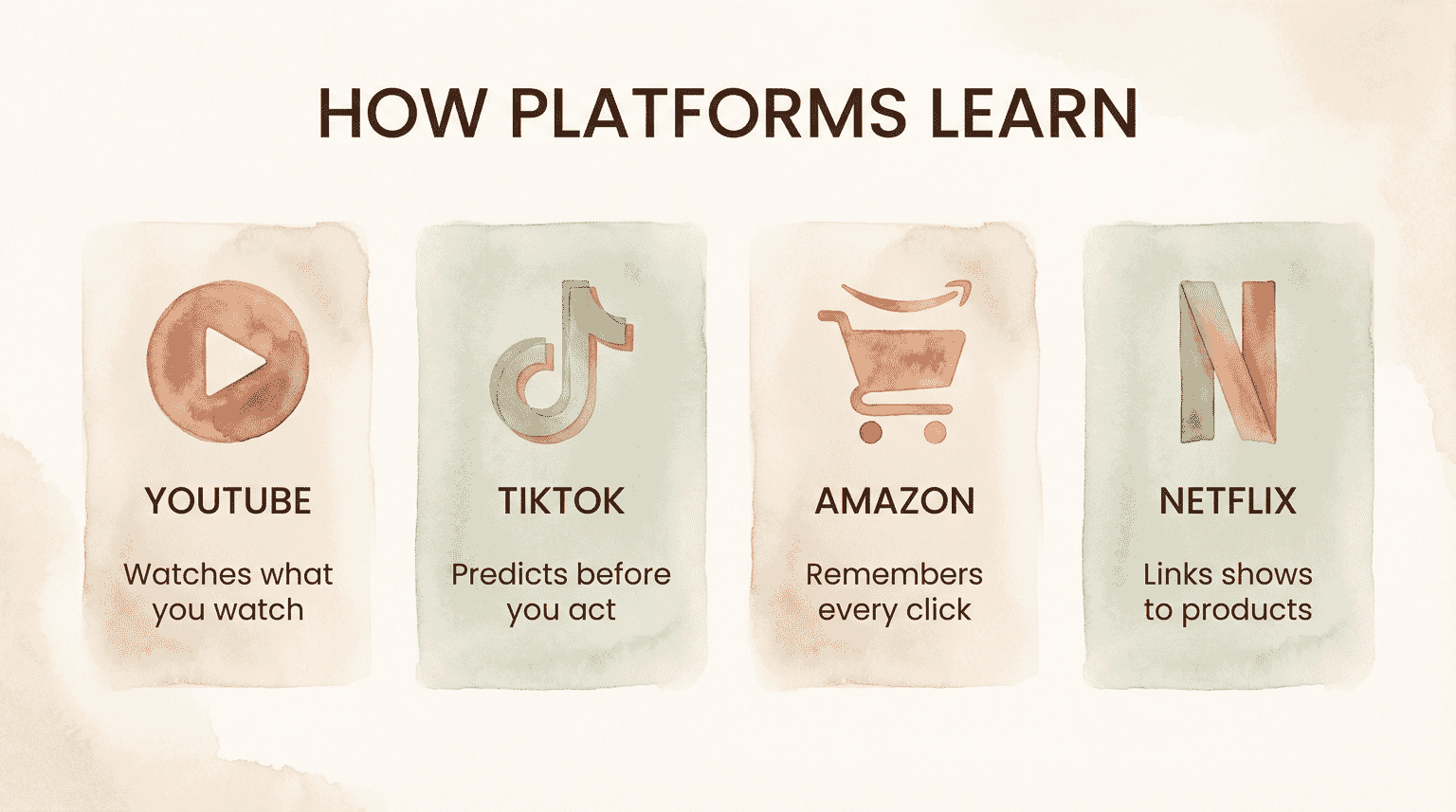

YouTube uses recommendation clusters based on what similar users watched. If your child watches one toy unboxing, the algorithm notes this engagement and serves more. Content creators know this—they A/B test thumbnails to maximize clicks, systematically optimizing for attention-grabbing features. The result: a self-reinforcing loop where engaging with any toy content triggers an avalanche of more.

TikTok’s “For You” algorithm combines collaborative filtering (what similar users liked) with content-based filtering (what resembles previously engaged videos). According to research on TikTok’s recommendation systems, between one-third to half of the first 1,000 videos shown to new users are selected based on TikTok’s predictions of their preferences—before the user has done anything at all.

Amazon’s suggestions operate on purchase and browsing history. If your child points at something once, that category populates recommendations for months. If they have any access to your account—even briefly—the algorithm learns.

Netflix tie-ins work differently but toward similar ends. Watching a show featuring collectible toys leads to recommendations for similar shows, which feature more collectible toys, which creates a desire feedback loop disguised as entertainment choices.

Each platform is running experiments on your child’s attention—constantly testing what keeps them engaged longest.

Why Children Can’t Look Away

I’ve watched this happen with my own kids across every age, and the pattern is consistent: children simply cannot resist algorithmic influence the way adults can. Research explains why.

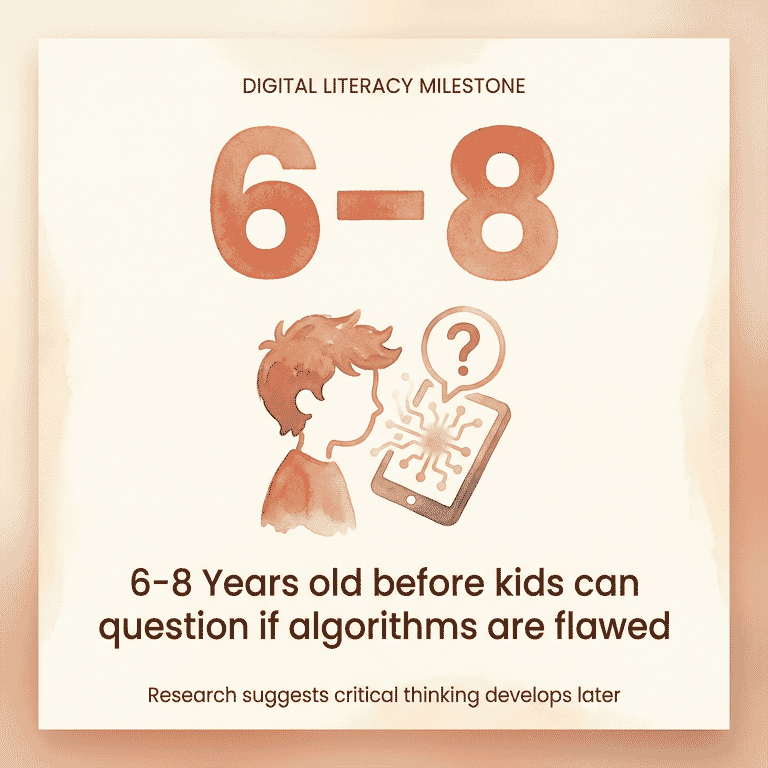

Stanford’s 2025 analysis of children’s AI comprehension found that children cannot understand how AI and algorithmic systems work until early adolescence. Children aged 6-8 can begin questioning whether AI is flawed, but they struggle with the abstract reasoning required to understand: this recommendation exists because someone profits from my attention.

This finding from Stanford researchers explains so much about why reasoning with young children about screen content feels impossible.

Before age 8, the abstract thinking required to understand “this was shown to you on purpose” simply isn’t developed yet. They experience recommendations as discoveries, not manipulation.

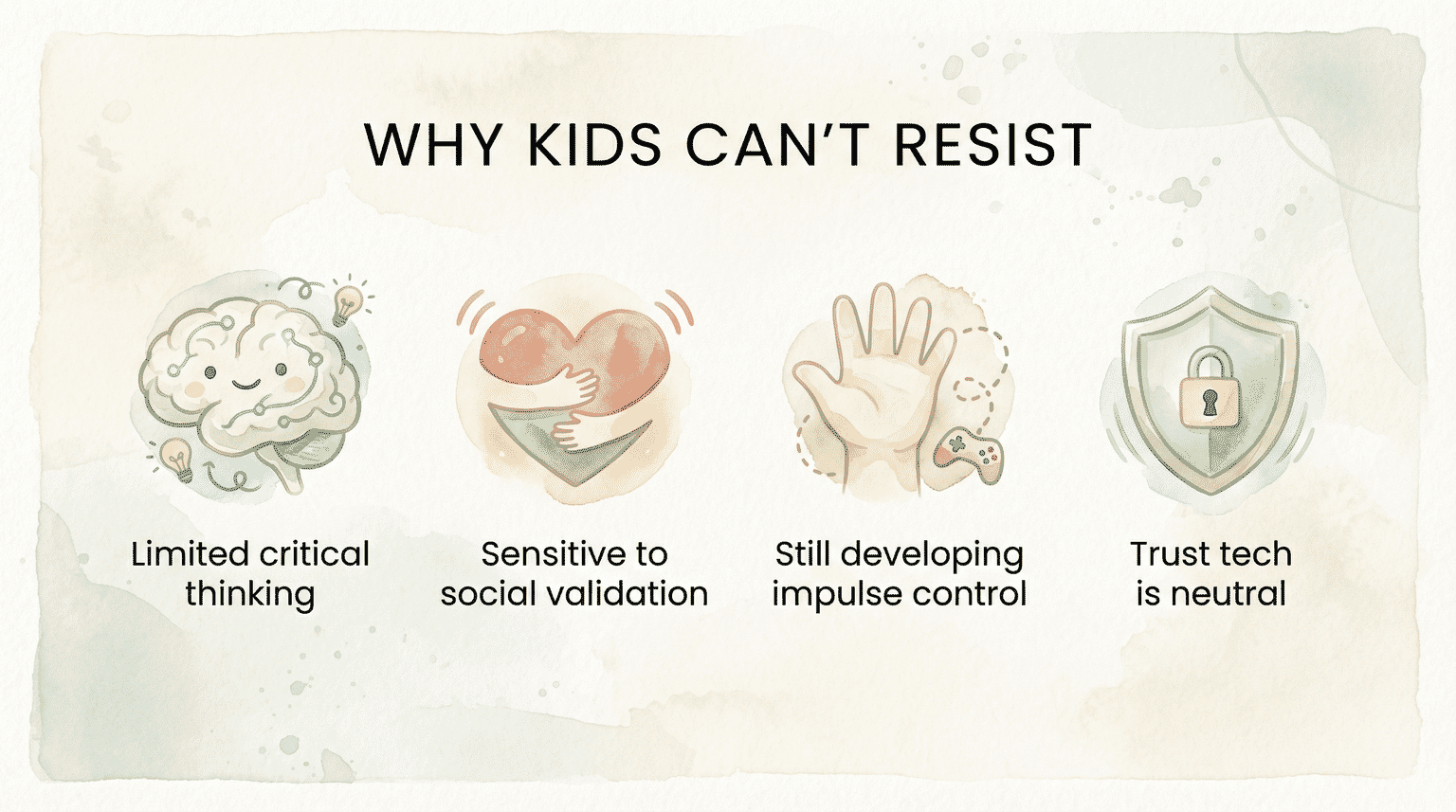

The TikTok governance study documented four specific vulnerabilities:

- Limited critical evaluation skills prevent recognition of engagement-maximizing design

- Heightened social sensitivity increases responsiveness to likes, views, and validation metrics

- Developing impulse control limits resistance to infinite scrolling and autoplay

- Heightened trust in technological systems—children assume recommendations are neutral

That last point deserves emphasis. Your eight-year-old genuinely believes the algorithm is showing them things because those things are good, not because they’re engineered to be irresistible. They experience recommendations as discoveries, not as manipulation.

In my house, this looks like my 10-year-old explaining why she “found” a product—as if she stumbled upon it organically rather than having it served directly to her attention after behavioral signals she didn’t know she was sending.

The Wish Fulfillment Trap

Here’s the mechanism that creates desire out of nothing:

Your child sees thumbnails featuring luxury items, expensive toys, lavish bedrooms, or the latest must-have product. They don’t own these things. They can’t have these things. But the imagery is specifically designed to trigger wanting.

When they engage—even hesitating on a thumbnail counts—the algorithm registers interest and serves more. More exposure normalizes the desire. Normalized desire becomes requests. Requests become pressure.

The Bipartisan Policy Center describes this as a “feedback loop”: algorithmic recommendations entice users to remain on platform longer, and increased time online correlates with increased exposure to age-inappropriate content and unrealistic expectations. A child drawn to one “wish fulfillment” video will see more, narrowing their feed toward content that manufactures wanting.

Research on children’s natural play preferences reveals a stark contrast. Studies on parent-child game behavior found that 72-82% of children ages 3-6 consistently prefer painting, handicraft, and creative play activities. These preferences remain stable across development. What algorithms promote changes constantly—chasing engagement, not genuine interest.

When thinking about how screens shape what children expect, this distinction matters enormously. Your child may naturally love building with blocks or creating art. But after enough exposure to algorithm-curated content, they’re requesting products they’ve been shown rather than expressing organic interests.

How Quickly the Bubble Forms

The speed of algorithmic narrowing shocked me most.

Research cited in the TikTok study found that after just 5-6 hours on platform, almost half of videos shown to accounts mimicking 13-year-olds were potentially harmful mental health content—ten times the volume served to accounts without mental health signals. The algorithm identified “interests” and amplified them rapidly.

Even more disturbing: researchers found that simply changing a username from “Sarah” to “Sarah Lose Weight” resulted in 12 times more self-harm content being shown. The system responded to that single signal immediately.

For toys and products, the mechanism operates similarly. One engagement with unboxing content signals interest. The algorithm amplifies. Soon the child’s entire feed reinforces a specific desire that didn’t exist organically.

This explains why your child’s requests can feel so sudden and intense. They haven’t gradually developed interest—they’ve been algorithmically immersed in manufactured want.

Breaking the Bubble

So what can parents actually do? Stanford researchers and developmental experts offer concrete strategies.

Choose platforms with human curation when possible. Apps and services where content is selected by people—not predicted by algorithms—reduce the feedback loop effect. Research found toddlers using educational apps with adult scaffolding had significantly larger learning gains than those using apps alone. The same principle applies to older children: human involvement interrupts algorithmic narrowing.

Co-view and actively discuss. This isn’t about hovering—it’s about being present enough to ask questions. “Why do you think you’re seeing this video?” “Have you noticed you’re seeing a lot of similar things?” Even basic conversation helps children develop awareness they can’t develop alone.

Disrupt the algorithm deliberately. Search for content your child hasn’t requested. Watch videos together that break the recommendation pattern. Platform algorithms struggle with inconsistent signals.

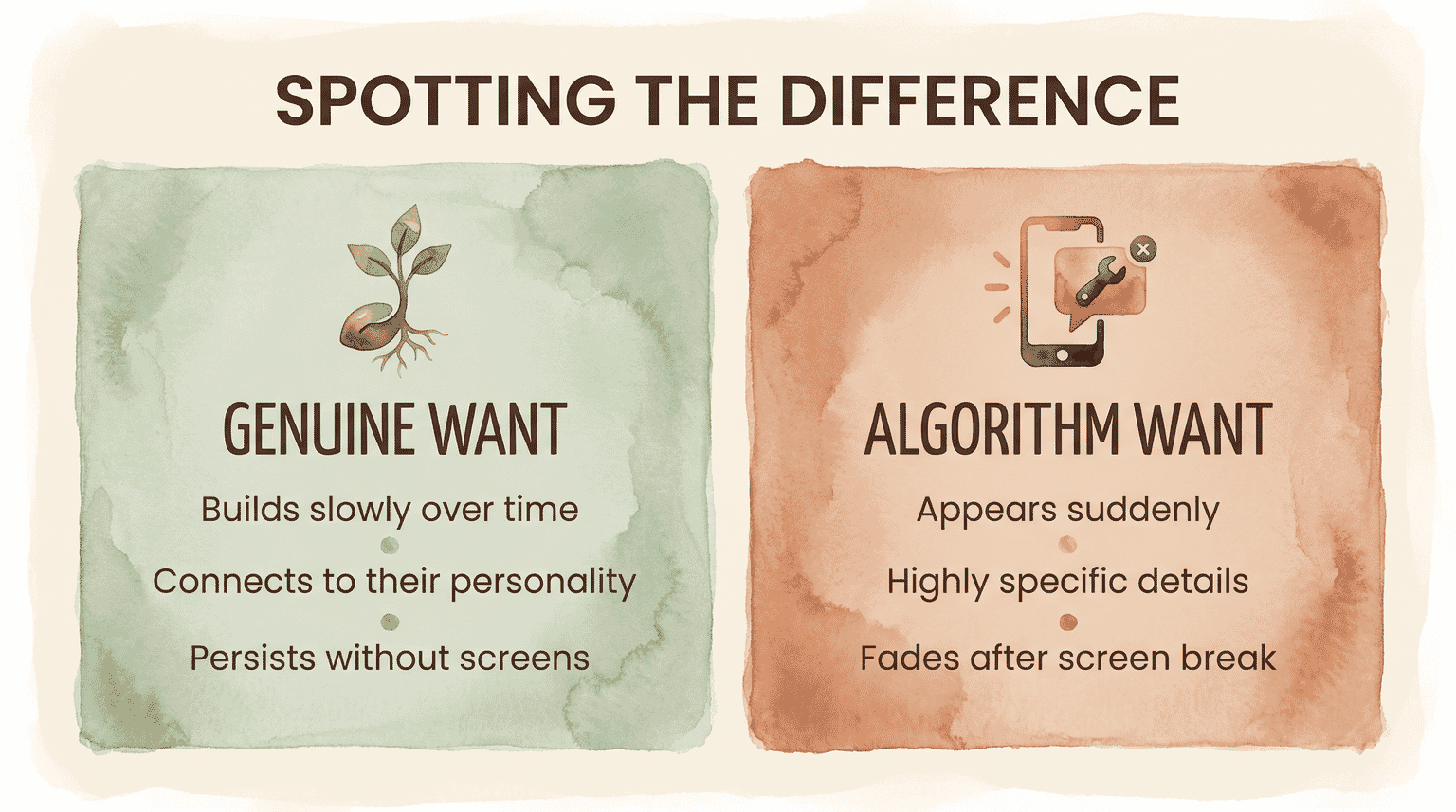

Distinguish algorithm-driven from genuine interests. After a week away from screens, which toys does your child still mention? Which interests persist without reinforcement? The desires that survive digital fasting are more likely organic. This becomes relevant when evaluating children’s wishlist apps—knowing whether the wishes are genuine or algorithm-generated changes how you respond.

Have age-appropriate conversations about digital influence. Children 6-8 can begin understanding that recommendations aren’t neutral—but they need adults to explain this explicitly. Developmental psychologists note this age group can perceive AI as flawed when guided, but they won’t reach this conclusion independently.

The research on gaming versus traditional play becomes relevant here too. Screen-based play keeps children in algorithmic environments; hands-on toys offer breaks from the feedback loop.

When the Algorithm Comes for Parents Too

Here’s what I didn’t expect to find: parents aren’t immune.

Technology and emotions researcher Pamela Pavliscak puts it directly:

“All of the tech industry is preying on the vulnerability of parents as well as children.”

— Pamela Pavliscak, Researcher at ChangeSciences

After your child engages with toy content, platforms serve you targeted ads for those products. Your own feeds begin featuring “solutions” to parenting concerns you’ve searched. The algorithm notices your late-night anxious Googling and responds with content that amplifies that anxiety—then offers products.

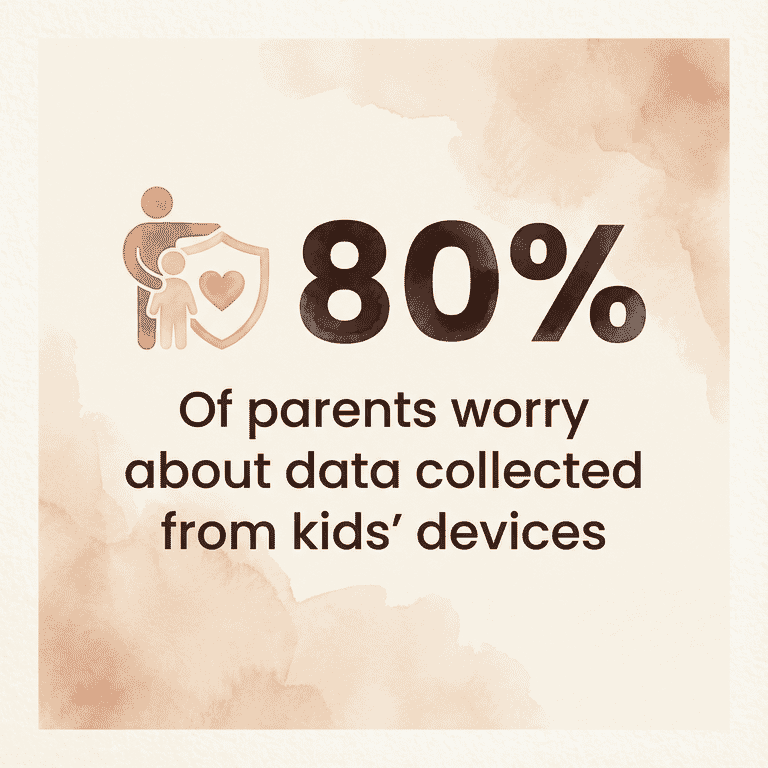

A study from Bangor University found 80% of parents expressed concern about data access from children’s connected devices. Nearly half reported discomfort with internet-connected toys processing their children’s emotional data.

That discomfort is warranted. The same systems watching your child are watching how you respond to your child’s requests.

Technology researcher Jag Minhas warned of the long-term stakes:

“We might breed a generation of people who have a very confined set of personalities that were influenced heavily by algorithms.”

— Jag Minhas, Technology Researcher

This isn’t alarmism—it’s awareness. The same systems engineering your child’s desires are engineering your responses to those desires.

What This Means for Gift-Giving

Understanding the algorithm doesn’t mean rejecting all technology. It means recognizing that when your child desperately wants something, the first question worth asking is: where did this want come from?

Desires that emerge from play, from genuine interests cultivated over time, from watching a sibling enjoy something—these feel different from algorithm-generated wanting. They persist. They connect to your child’s actual personality.

Desires that appear suddenly, intensely, and with surprising product specificity often trace back to systematic exposure you didn’t control.

As a parent, you can’t eliminate algorithmic influence. But you can recognize it, interrupt it, and help your child develop awareness of it. That awareness—more than any content restriction—is what protects them as they grow into a world where algorithms will only become more sophisticated.

The algorithm knows what your child wants. Your job is helping them know themselves better.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do social media algorithms target children?

Algorithms target children through attention-capture design: University of Michigan researchers found 91.5% of recommended videos use “drama and intrigue” tactics, 79.1% feature “visual loudness” (bright colors, extreme expressions), and nearly half show “lavish excess and wish fulfillment”—luxury items and toys children can’t have, specifically designed to trigger desire.

What age can children understand algorithms?

Children cannot understand how AI and algorithmic systems work until early adolescence, according to Stanford University research. Children ages 6-8 can begin questioning whether AI is flawed, but they still struggle with abstract reasoning required to understand algorithmic influence. Before age 8, children tend to place heightened trust in technological systems, assuming recommendations are neutral.

How can I tell if my child’s request is algorithm-driven?

Algorithm-driven desires tend to appear suddenly with unusual product specificity—your child knows features, colors, and details you’ve never discussed. Try the “digital fasting test”: after a week away from screens, which wants persist? Genuine interests survive without reinforcement; algorithm-generated desires often fade without the feedback loop maintaining them.

Which platforms are safest for children?

Platforms with human-curated content rather than algorithmic recommendations reduce the feedback loop effect. Look for apps and services where people—not prediction systems—select what children see. Co-viewing any platform provides protection, as research shows adult involvement significantly improves outcomes regardless of platform choice.

I’m Curious

Have you noticed the algorithm shaping what your kid wants? I’d love to hear whether the “digital fasting test” has revealed anything—or whether some wants just persist regardless of screen breaks.

Your algorithm stories help other parents recognize the patterns too.

References

- University of Michigan/JAMA Network Open (2024) – Analysis of algorithmic content recommendations on video-sharing platforms

- ResearchGate TikTok Study (2025) – AI-driven recommendation systems and children’s developmental vulnerabilities

- Stanford University (2025) – Developmental considerations for children and AI interaction

- Bipartisan Policy Center (2023) – Social media algorithm benefits and risks analysis

- Bangor University – Research on emotional AI in children’s toys and devices

Share Your Thoughts